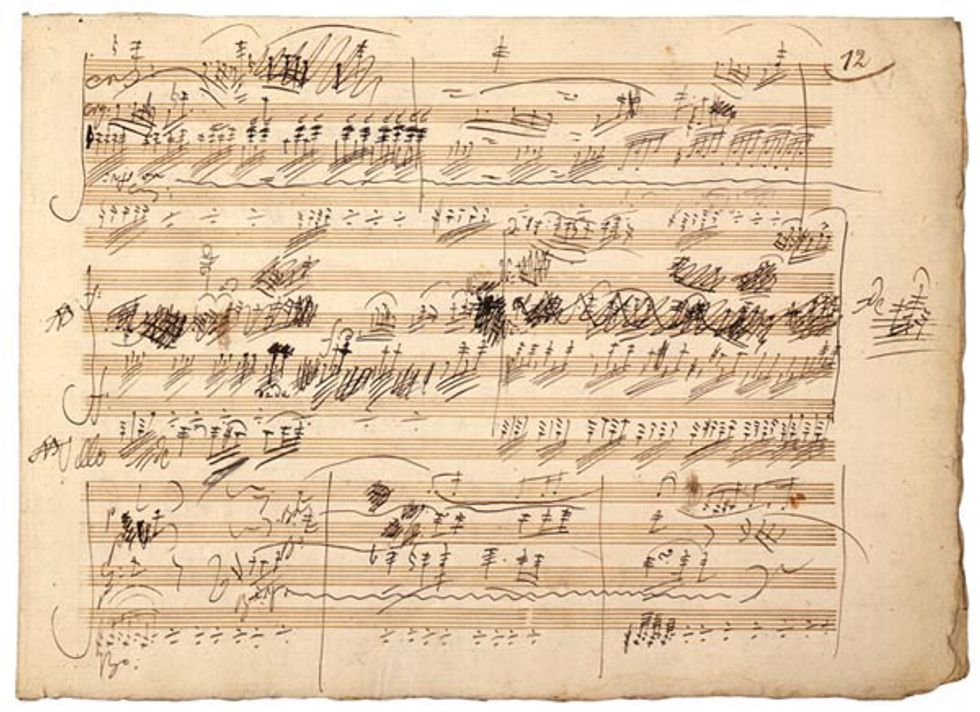

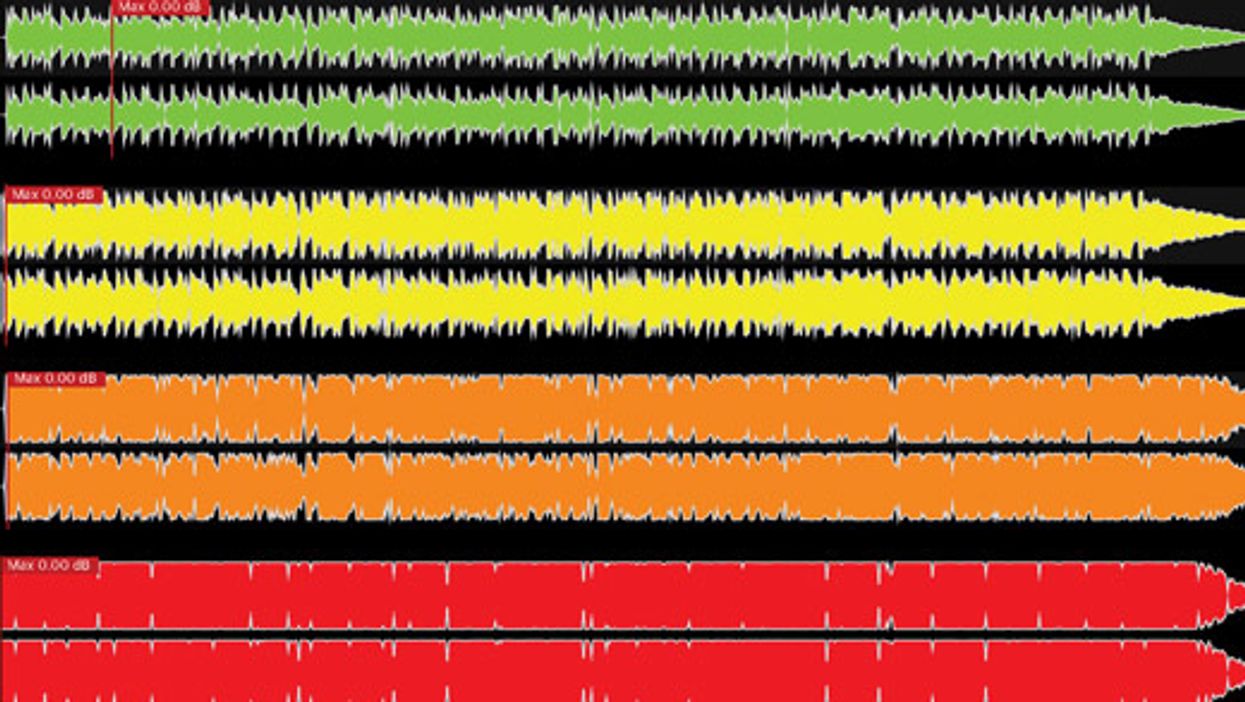

Image 1: Beethoven probably wouldn’t have wanted the world to view his raw manuscripts, but two centuries later they reveal much about the man and his music. You don’t need to read notation to appreciate how the composer

bled for every note.

Let’s be clear: It’s a bad idea to break the law. We at Premier Guitar strongly discourage any illegal activity, be it robbery, mayhem, or smuggling dangerous liquor-filled chocolates from Canada into the U.S. And you definitely shouldn’t download illicit files.

But any scofflaw who did happen to type the search phrase “Multitrack Masters” into Google or YouTube would uncover amazing things. Theoretically speaking.

Not for personal use. The files in question feature dozens of familiar classical and modern rock recordings, but with the individual parts isolated. I’ve heard they were created for the Rock Band video game franchise. Apparently the rights holders, lured by fresh licensing income, allowed engineers access to the master tapes, unlocking hundreds of individual performances. Someone leaked the material, and now the individual tracks are part of the public record. (Or at least they should be—more on that in a bit.) This mind-boggling material reveals volumes about how great musicians played, great bands collaborated, and great producers corralled their talent into great recordings.

This month I’d like to talk about some of the lessons gleaned from these tracks. (Mind you, I didn’t glean them. I heard the following observations from a friend of a friend of the cousin of the guy who installed the new faucet in my studio bathroom. He said it was okay to share his words with you, because I would never let illegal files pollute my morally upright hard drives.)

Here are some things he discovered among the Multitrack Masters and other illicitly circulated tracks.

Blistering Beatles. Holy moly, the Beatles tracked their guitars bright! They routinely set their amps to “shriek,” and their engineers added additional treble at the mixing desk. Partly, it was pragmatic: The group’s middle-period masterpieces were recorded on 4-track tape with much track bouncing. Each bounce ate highs, so treble steroids were required. But still, solo the guitars from, say, the opening track of Sgt. Pepper and consider what meager percentage of today’s players would be caught dead using such icepick tones. Lesson: Guitars tones don’t have to be attractive and balanced. They just have to sound that way in context.

Slippery Stones. The Stones are rightfully famed for their sublime grooves. But listening to soloed tracks reveals that each part tends to groove in a different way—there’s nothing “tight” about it! Feels vary from player to player. Beats fail to land together. But did you ever wish the performances had been aligned in Pro Tools? Me neither. Lesson: Groove isn’t about everyone playing the same subdivisions in lockstep.

Marley mixology. How I’ve marveled at the rich, deep bass guitar tones on such late Marley albums as Uprising. But while beautifully performed, Aston Barrett’s soloed bass tracks are nothing special sonically—it’s just a garden-variety J bass with the lows pushed a bit. But dig the drums: There’s little top-end click on the kick, and the snare has had all its lows surgically removed. Lesson: Sometimes the only way to make something big is to make something else small.

Leaky Zeppelin. We often fret about leakage when we set up in the studio, but like the honey badger, Zep just didn’t give a shit. You can tell they set up close together, and you can often hear all the instruments on every track. (On some bass takes, Bonham is as loud as JPJ.) Lesson: Sometimes we should encourage leakage instead of fighting it.

Messy Marr. I was dumbfounded years ago when Johnny Marr told me how many guitar tracks he typically recorded with the Smiths. Really? Fifteen guitars on the deceptively simple “This Charming Man?” Yes, really. Marr’s isolated guitar stems from that song and “Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One Before” reveal mountains of overdubs—and not clean, tight ones, either. Clean and distorted electric guitar and multiple acoustics are all hurled into the melting pot. The result is just the right amount of “blur” to reinforce the riffs while adding subtle variation and mystery. Lesson: Magic can reside in near-subliminal details.

Screw the solo buttons. There are countless other lessons, from Stevie Wonder’s non-synchronized delays to Queen’s uncannily accurate timing and intonation. But if there’s one overarching lesson, it’s that nowadays we spend far too much time scrutinizing and scrubbing individual tracks, aligning them in pitch and time. It’s clear that these creators spent little time pressing solo buttons, focusing instead on how parts worked together. Lesson: Forest, not tree.

Copyrights and copywrongs. Intellectual property is a complex issue, and I’m not suggesting that everyone should have free access to any and all copyrighted material. But I’m far from the first to note that the copyright deck is stacked, and not in favor of fans or artists. It’s all about maximizing revenue for the zillionaires atop the pyramid. After all, they’re the ones who purchased our current copyright laws.

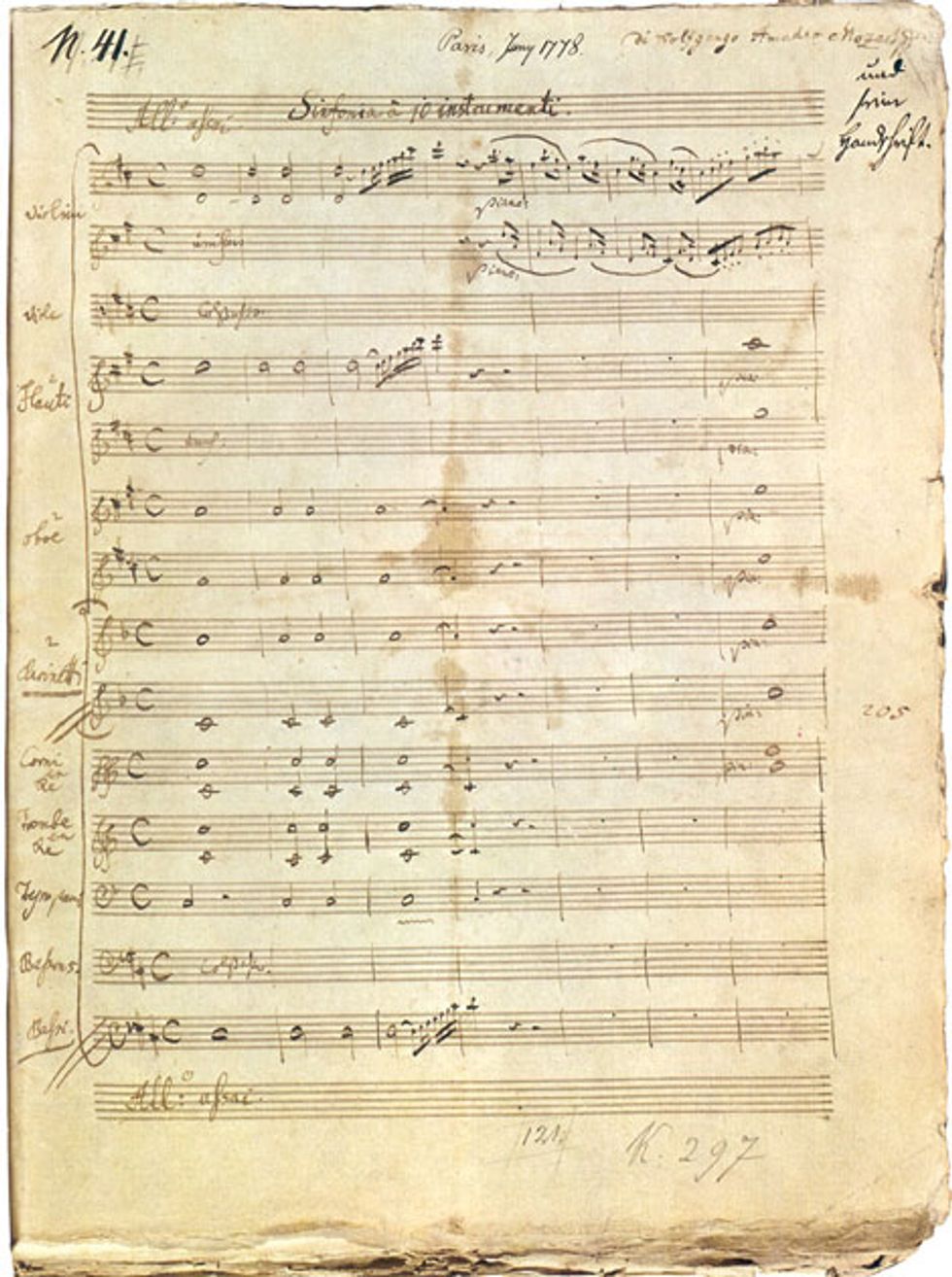

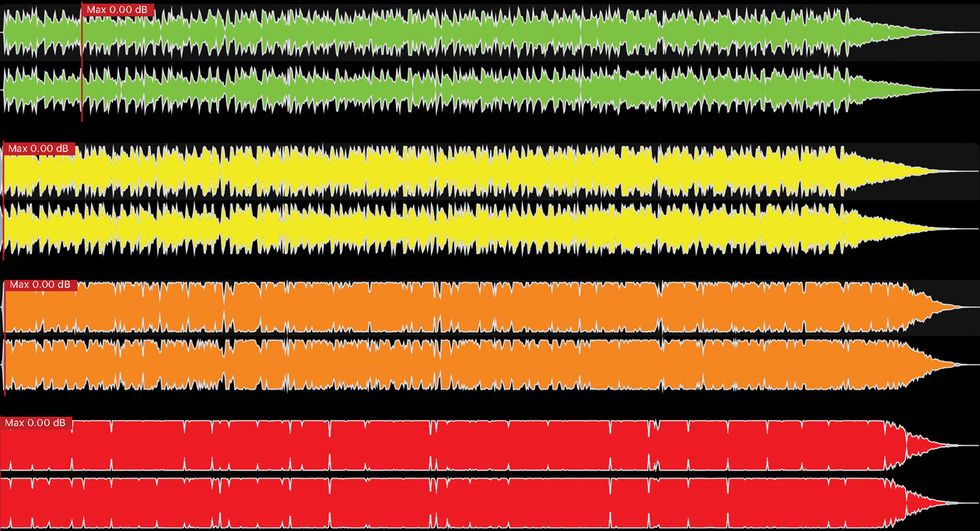

Image 2: Mozart manuscripts tend to be tidy and correction-free. He had everything worked out in his head—he just needed to slow down long enough to write it down. It’s a window into his remarkable mind.

There’s another issue: The musicians who created this stuff intended that we consume it in its perfected form—they probably didn’t want us peeking into their closets or running white gloves along their windowsills, artistically speaking. Don’t they have the right to determine what the public should hear?

Yeah—to a point. But I can’t help thinking of classical music scholarship, which is often based on scrutinizing raw manuscripts and corrected proofs. Such artifacts teach us how great artists created great art in ways the final product does not.

Bloody Beethoven vs. meticulous Mozart. Take Beethoven’s famously chaotic manuscripts, for example. You don’t even need to read music to feel the emotion behind the page in Image 1. Dig those angry, frustrated quill strokes—it’s amazing the paper didn’t catch on fire! Every note was a matter of life and death, and Ludwig bled for each one.

Compare that to the Mozart manuscript in Image 2. Mozart’s pages usually have few corrections. Wolfgang Amadeus already had everything worked out in his head—he just had to sit still long enough to jot it down.

Documents like these reveal aspects of artistry you’d never glean from concerts, recordings, or published scores. Same with literature: For example, Google “Great Gatsby Manuscript Images” and you’ll find F. Scott Fitzgerald’s handwritten original, peppered with deletions and word substitutions. Try it with Hemingway or Joyce—same result. Does the knowledge that Beethoven or Joyce didn’t nail it perfectly the first time diminish their art or our appreciation of it? Hell no—the opposite!

So it’s okay to view Beethoven’s work in progress, but he’s been dead since 1827. How about Igor Stravinsky, arguably the 20th century’s greatest composer? His work is still copyrighted, and he died in 1971. How about Hendrix, who died the same year? How many years after Hemingway’s death must pass before we peek into his notebooks?

Opinions vary. But my plumber’s friend’s cousin’s cousin argues that this stuff ought to be freely available for study purposes. It should be accessible online via web-based music players on the British Museum and Smithsonian sites. Sure, music belongs initially to its creators. But over time, as it takes its place in the collective consciousness, it becomes part of our hearts and minds. In a very real sense, it becomes ours, and we should have access to it.