We’re in the process of exploring ways to

make triads sound bigger than typical

three-note voicings. The trick, as we’ve learned,

is to turn close-voiced triads into open-voiced

forms. This simple technique converts a triad

that occupies a single octave (close-voiced)

to one that spans more than an octave

(open-voiced).

In the first installment of our series

(“Hybrid-Picking Pals,” January 2011 PG),

we expanded a root–3rd–5th triad by dropping

its middle note by an octave. Then we

saw what happens when we raised that middle

note an octave (“Going Up?,” February

2011 PG). In both lessons, we generated a

fistful of major and minor forms that sound

bigger—and arguably more intriguing—than

standard-issue triads. If you missed either of

these lessons or want to refresh yourself on

the two voicing techniques, they're linked above.

In this third and final part of our series,

we’ll integrate some of the different forms

we’ve discovered thus far and continue to

blanket the fretboard with fresh chordal colors.

But first, let’s look at one more voicing technique

in which we raise and lower notes in a

close triad to generate yet another set of major

and minor grips.

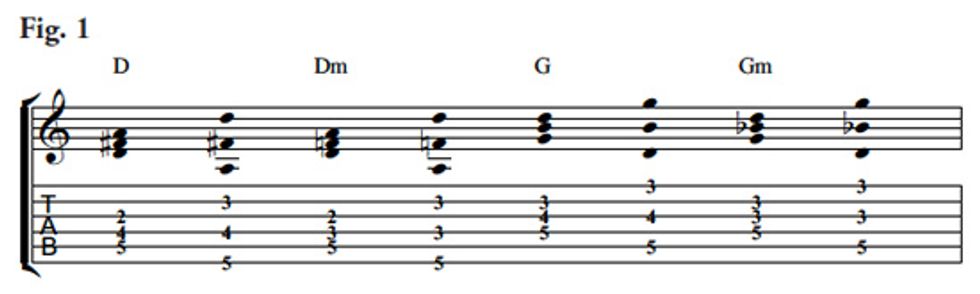

Fig. 1 begins with a root-position, close-voiced

D triad, D–F#–A (root–3rd–5th) on

strings 5, 4, and 3. If we raise the bottom note

up an octave and simultaneously drop the top

note down an octave, we get the second voicing

in this example, A–F#–D (5th–3rd–root).

Whoa! Now instead of a chord that covers

a mere fifth, we have one that stretches an

octave and a fourth, yet still only contains

three notes. Notice how this second voicing

falls on strings 6, 4, and 2. When playing a

chord voiced entirely on non-adjacent strings

like this, attack it using either a hybrid pick-and-fingers or pure fingerstyle technique.

Download Example 1 audio...

The next two chords in this example illustrate

how the process works identically with

minor triads. Here, we start with a root-position,

close-voiced Dm (D–F–A) on the same

string set and then propel the lowest and highest

notes respectively up and down an octave

to create an open Dm (A–F–D). We began

with a root-b3rd-5th voicing and converted it

to a 5th-b3rd-root structure. Make sense so far?

To finish this example, let’s apply the same

technique to root-position, close-voiced G

and Gm triads on strings 4, 3, and 2. By

doing so, we generate open G and Gm triads

on strings 5, 3, and 1. Again, these new

chords fall on non-adjacent strings and span

an octave and a fourth.

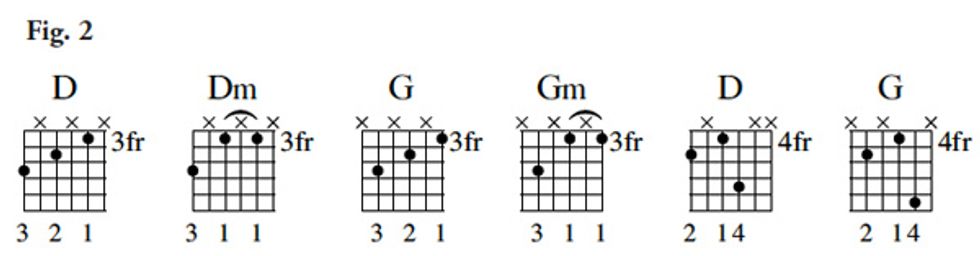

Fig. 2 shows the open chords we just generated—D, Dm, G, and Gm—stripped away

from the close triads that spawned them. The

last two grips, D and G, are simply refingered

versions of the major chords that preceded

them in this example. It’s handy to know several

ways to fret the identical voicing, because

sometimes one grip works better than another

to link to neighboring chords in a song.

Download Example 2 audio...

If you’re up for a five-fret stretch, you can

convert grid 5’s D to Dm by simply lowering

the 3rd (on string 4) to a b3rd. But, unless

you have exceptionally long fingers, grid 6’s

G doesn’t offer this flexibility because this

form already incorporates five frets, and

dropping the 3rd to a b3rd would yield a

whopping six-fret stretch.

Okay, now we’re ready to put our open triads

to work. Even the most mundane progressions—

ones you’ve played and heard a million

times—take on a fresh, new life when you

arrange them using open-voiced triads.

For instance, how about D–G–C–G?

Rather than grabbing conventional chord

forms, let’s play this progression using voicings

and concepts we’ve covered in this and the

previous two lessons. Fig. 3 puts a new twist

on the I–IV–bVII–IV workhorse, giving it a

soul-jazz flavor. Add some rotary speaker emulation

and you’ll be grooving and grinding like

a Hammond B-3 player.

Download Example 3 audio...

As you work through this four-bar phrase,

notice how we’re playing different voicings

for the C and G chords that occur in bars 2

and 4. You can spice up even the most basic

progressions by alternating inversions of open

triads as you navigate the changes.

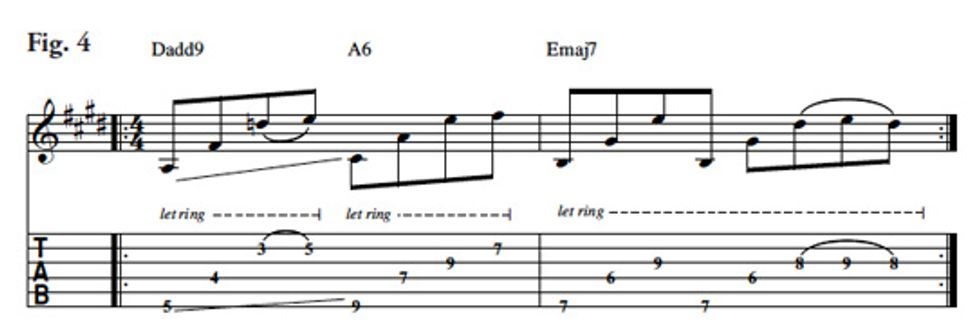

The fun begins when we melodically embellish

open triads to create chords that go beyond

major and minor tonalities. Fig. 4 offers a

taste of this, with its add9, major 6, and major

7 sounds. As you work out these arpeggios,

notice how each chord is based on an open

triad that we then color with one extra tone.

Also, pay attention to the let ring markings—the goal is to have the chord tones sustain and

overlap to create rich harmonic textures.

Download Example 4 audio...

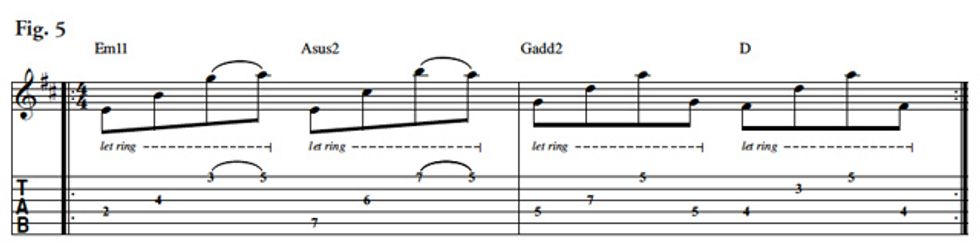

The madness—sorry—the adventure continues

in Fig. 5. Thanks to open triads, we’re

able to generate min11, sus2, and add2 chords

with minimal effort. Pretty cool, huh?

Download Example 5 audio...

Once you get a feel for open triads, you’ll

discover many ways to use them to create

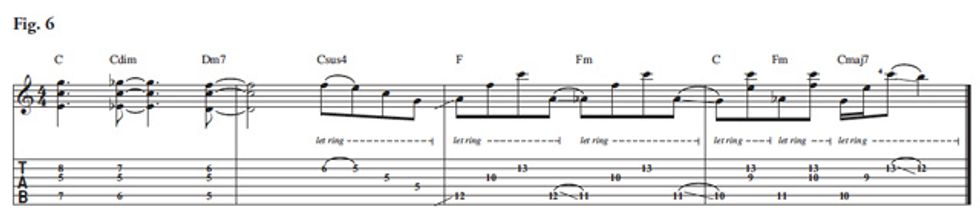

sophisticated harmony. With its diminished,

minor 7, sus4, and major 7 colors, Fig. 6 offers

a glimpse of the possibilities. This example also

underscores open triads’ elasticity—especially

compared to big, clunky barre chords—and

how easily these grips let you move selected

notes while holding others. This type of harmony

lets you sound more like a string trio or

horn section and provides a welcome alternative

to simply strumming block chords.

Download Example 6 audio...

We’ll begin exploring the fascinating world

of quartal harmony in next month’s lesson. See

you then.

Andy Ellis is a veteran guitar journalist

and Senior Editor at PG. Based

in Nashville, Andy backs singer-songwriters

on the baritone guitar, and also

hosts The Guitar Show, a weekly on-air

and online broadcast. For the schedule,

links to the stations’ streams, archived audio

interviews with inspiring players, and more,

visit theguitarshow.com.

Andy Ellis is a veteran guitar journalist

and Senior Editor at PG. Based

in Nashville, Andy backs singer-songwriters

on the baritone guitar, and also

hosts The Guitar Show, a weekly on-air

and online broadcast. For the schedule,

links to the stations’ streams, archived audio

interviews with inspiring players, and more,

visit theguitarshow.com.