Musically speaking, things have come full circle for Robyn Hitchcock. The unmistakably British singer-songwriter’s career has gone through numerous permutations, beginning with the seminal late-’70s art rock band the Soft Boys, and including incarnations with the Egyptians and the Venus 3, not to mention various solo albums and projects, among them the critically acclaimed 2004 collaboration with Gillian Welch and Dave Rawlings, Spooked.

Though the sonic backdrops for Hitchcock’s musings have been widely varied during his prolific 40-plus-year career, his distinctive voice, droll wit, and gift for at times haunting verbal imagery have been constants throughout. And now, at age 64, he’s gone back to his roots with an eponymous new album that harks back to his Soft Boys days.

Hitchcock has described Robyn Hitchcock as “an ecstatic work of negativity,” and while that might seem to be just an example of the artist’s dry humor, it’s also a sharp assessment. It’s an album (and perhaps an entire career) that explores, in a nutshell, how the world is screwed, humankind is woefully misguided, and yet life is still somehow beautiful and there’s joy to be had.

For example, “Virginia Woolf” considers the legacies (and suicides) of Woolf and Sylvia Plath. It recalls the work of legendary Pink Floyd founding member Syd Barrett, one of Hitchcock’s musical heroes, with a wall of trippy, interlocking guitar tracks that pulsate and percolate.

Robyn Hitchcock is a compelling collection of songs, and the guitars are glorious throughout—a credit to Hitchcock, guitarist Anne McCue, and producer Brendan Benson, who has a keen ear and made his collection of guitars and vintage amps available to them. (See “Studio Spangle” for a short interview with Benson about making the album.) From dreamy reverb and tremolo tracks to in-your-face overdriven guitar explosions, the album is a shining example of employing guitars to serve the songs, as opposed to the other way around.

The rhythm section features drummer Jon Radford and bassist Jon Estes from Nashville instrumental band Steelism, and Nashville pedal steel legend Russ Pahl also played on the record. Background vocals were provided by Grant-Lee Phillips, Gillian Welch, Wilco’s Pat Sansone, and Hitchcock’s partner, Australian-born singer-songwriter Emma Swift.

At a coffee shop in the East Nashville neighborhood where he now lives with Swift, Premier Guitar recently sat down with Hitchcock to discuss the making of Robyn Hitchcock. He candidly quipped on further ranging subjects from seeing Jimi Hendrix at the Isle of Wight Festival, to taking songwriting advice from Johnny Marr, and the need for human evolution.

and get the plague.’”

What inspired your move to Nashville?

Emma was living here when we met four years ago. She’s from Sydney. I’ve been coming here for a long time. I made Spooked here [with Gillian Welch and Dave Rawlings] in 2004 at Woodland Studios. They’re my songs, but it’s as if I managed to sneak into one of their records … so it’s just a bit of a dream.

And Grant-Lee Phillips moved here. He’s an old friend of mine from L.A. Meanwhile Brendan Benson, quite coincidentally, contacted me when I was living on the Isle of Wight, and said, “Would you be interested in collaborating in some way?”

You were in the Isle of Wight before you moved?

Yeah. The last big thing that happened there was the festivals, which I went to in ’69 and ’70. Dylan and Jim Morrison and the last Hendrix show. The island was thronged with a quarter of a million hairy groovers who turned up in a place that was full of essentially conservative people.

I read that your dad hipped you to the fact that Dylan, who you liked, was playing there.

He did, bless him. He wasn’t a Dylan fan—he liked Joan Baez. I think he had the hots for her. Dylan was too abrasive for him. Dylan was a badge of our generation, not his, though he liked the Weavers.

He could see things that might work for me that wouldn’t necessarily work for him. He also famously took this transistor radio in to my sister and I while we were watching a scientific puppet show on television, and said, “You might like this.” And it was the Beatles. We said, “Well, we’re watching telly.” And he said, “You can always watch the telly and turn the sound down.”

The following week we didn’t even bother to turn the television on at all. We just listened to the Top 20. This was where you could hear the Beatles.

On his self-titled new album, Robyn Hitchcock took gear cues from producer Brendan Benson, choosing a Charles Whitfill “T” Style, a ’72 Fender Tele, and a ’60s Supro amp, all owned by Benson.

And you saw Jimi Hendrix?

Yeah, I did. I really enjoyed Hendrix. The Doors was a bit perfunctory. Jim Morrison had lost heart—it was just an hour of their greatest hits. I think it was one of the last shows they did.

And Hendrix died two weeks later, but Hendrix seemed much more vital. I don’t think he found it a very satisfactory gig, but he was obviously trying. He just seemed like somebody who was sick to death of playing 12-bar [blues] but couldn’t quite get away from it. So, he was trying to deconstruct it. How do I play a 12-bar in a way that I haven't done it before? And Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck and hundreds of other hairy men in flared trousers and grandpa vests haven’t done?

Because everybody was doing that by the summer of 1970. It was the easiest thing in the world to fake. Me and my friends at school did it … it was the great bullshit years of the guitar.

You’re in your 60s, but this sounds like a young rock album. I read somewhere that you said you made more autumnal records when you were young, and now you’re playing like someone who’s younger.

In a way things are more urgent now, because time is limited. I think turning 30 is the first big portal of age. Oh god, I’m not young, I’m not where it’s at anymore. What am I doing with my life? Lots of reasons to feel that 30 is a mournful age to reach. I think I probably did quite a lot of that back then. I’ve made a lot of reflective records.

Also, Brendan Benson said, “Could we make a record like you did with the Soft Boys? Two guitars, bass and drums.” I said, “Well I’m not fueled by quite the same rage.” I don’t know what he said, but it was something like, “Go and find some other rage to be fueled by.”

I sat in with Johnny Marr when I was on the Isle of Wight and he was playing in Portsmouth, which is the nearest big city to the island. We went over and I joined him for a couple of songs on the encores, which was fun. He said, “Write some fast songs!” You know, Johnny’s very intense. So, I think that’s when I wrote “Virginia Woolf,” which is semi-up-tempo.

Like his heroes Syd Barrett and Robbie Robertson, Robyn Hitchcock favors Teles. “To me,” he says, “the Stratocaster is for the higher-level guitarists. Richard Thompson and Eric Clapton. I’m more of a Tele bloke.”

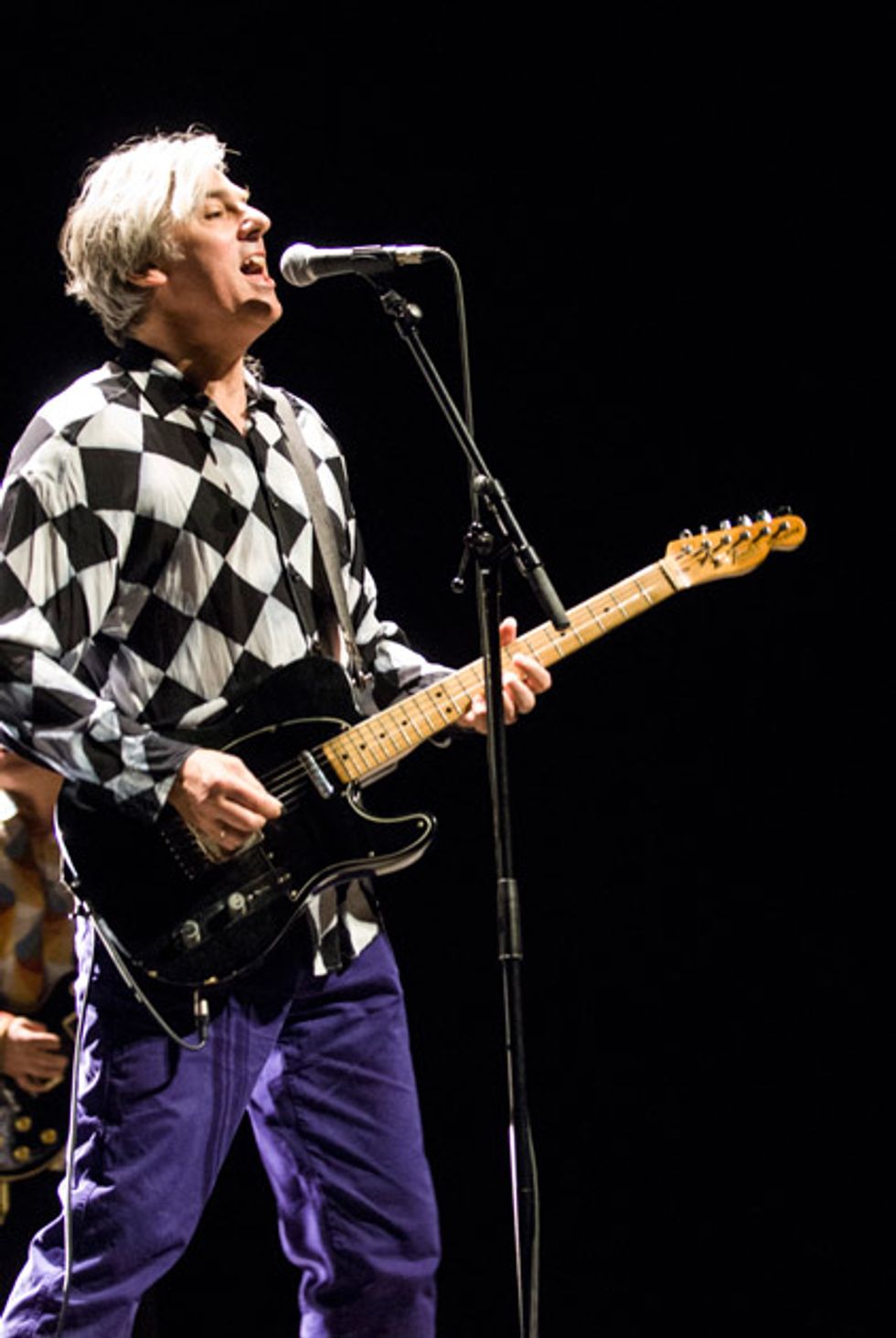

Photo by Jordi Vidal

An uplifting song about suicide! What inspired that song? It almost seems like an acknowledgment that life is complicated and difficult, and too much for some people, and they shouldn’t be judged.

Yeah, pretty much. Just because your perspective doesn’t work with life, and in the end, you will be destroyed or you have to destroy yourself, doesn’t mean your perspective is wrong. History has vindicated both those women, and their work lives on. Nobody says, “Well, they shouldn’t have written that stuff! They should’ve had psychoanalysis.” Now they’re not around for us to feel their pain. What they’ve left our culture with is something intense and beautiful. But life was also insufferable for both of them.

I love “I Want to Tell You About What I Want.” It almost seems like a very brief manifesto, with lyrics like “I want world peace / Gentle socialism / No machismo / And the only god shall be / The god of L-O-V-E.”

It is. It’s a manifesto. I’m not somebody who gives manifestos, as a rule. It was obviously written before Trump was even a twinkle in Satan’s eye.

My theory is that humanity, if it’s going to survive, will have to undergo some kind of physical evolution—probably to do with the pineal glands, and the brain—that makes people actually able to be more empathic. Like a very mild dose of telepathy. So, you don’t know everybody’s bank account numbers, you don’t know who’s sleeping with whom, you don’t know everybody’s ghastly secrets, but you can pick up from a long way away what people are feeling. You can’t just say, “Oh, fuck it, man. I’ve got the scones, I've got the chardonnay, they can just sit outside the city walls and get the plague.”

You got really great guitar sounds on the new album.

Anne and I both are kind of mid-weights. We’re not like heavyweight guitarists. I think she’s very good, and I’m good in my own way. I didn’t want the other player to be somebody who was just a mad shredder. I didn’t want to be shred by anybody but myself, if I was going to shred. And I find that, as a lead guitarist, whatever I have to say I can say in about 15 seconds. So I like to have little bursts of it.

Brendan didn’t play anything on the record?

No, but he got the sounds and he got the amps. Mostly, I think I’m playing one of Brendan’s Telecasters. I’m a Telecaster player by instinct, but I often wind up playing Strats. To me, the Stratocaster is for the higher-level guitarists. Richard Thompson and Eric Clapton. I’m more of a Tele bloke.

I know you mostly fingerpick. Do you ever use a flatpick?

If I possibly can, I use my fingers. I use my nails, and even sometimes just use my fingers. If you use a pick, you have twice as much force, but you have half as much control—and character.

Did you use any special tunings?

There are a few songs on the record that have tunings, but they’re slight tunings, not big David Crosby-style, everything’s different. I just dropped the B to an A and dropped the E to a D or something. “Time Coast” has that. You get that kind of Stones-y, chunky chord sound.

Robyn Hitchcock’s Gear

Electric Guitars1978 Fender Telecaster

2008 Fender Buddy Guy Standard Stratocaster (Polka Dot)

2011 Manson Custom T (Polka Dot)

2008 Eastwood Airline

1960 Hofner

Acoustic Guitars

1978 Fylde Olivia

2012 Fylde Olivia

1999 Larrivée

1990 Yamaha 12-string

1975 Yamaha

1960s Kay

1964 Gibson Folksinger

Spanish nylon string (origin unknown)

Amp

1960s Epiphone EA-50T Pacemaker Tremolo

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Skinny Top/Heavy Bottom strings (.010–.052)

Dunlop Tortex Pitch Black picks (1.0 mm, .88 mm, and .73 mm)

Who were some guitar players who influenced you?

I think you’re drawn to the kind of people you want to be, or in whose path you want to follow.

Because I never wanted to be a lead guitarist rather than a vocalist, I liked people who sang and played their own leads. The virtuoso in that would probably be Richard Thompson. I got into him a bit later. I was already in the Soft Boys. Syd Barrett I loved. I loved his singing, his songwriting, and his guitar playing.

Your voice at times reminds me of him.

Well, he was another English bloke. I realized that

I wanted to be Bob Dylan but I wasn’t a Jewish kid from Minnesota. I was a bloke from the Home Counties. And there was this bloke from the Home Counties of Britain, with a flat English voice.Plus,

it wasn’t just the voice, but the way he used words, the way Barrett was so pictorial, like Captain Beefheart, another hero of mine. But Beefheart didn’t play. He went through his guitarists. He would brutalize these young guys. He’d keep them in a coffin or whatever it was, and feed them on scraps of dry bread, and force them to work out what he was playing on the piano.

I love the sound of Beefheart’s guitarists as well—very precise, very low on effects. It was like the anti-Clapton. It was these sometimes quite dissonant chords, played very clearly in a chunky way. I think that was a Tele again. Barrett played a Tele. Robbie Robertson played a Tele when he played with Bob Dylan, the most exciting stuff. George and John, the Beatles. If you listen to “I Pray When I’m Drunk,” that’s basically us trying to get a sort of “Doctor Robert” sound from Revolver. Two clanging guitars over a sort of booming, slightly country rhythm section—like the way John and George played at the time when they were getting psychedelicized.

It seems like toward the end of the album—“Time Coast,” “Autumn Sunglasses,” and “1970 in Aspic”—there’s a lot of reflection on the passage of time.

Well in that way, I am showing my age. I’m just not doing it sounding like a crumbling old chap on a walking stick. You can’t escape time, because if there was no time, there would be no time in which to move. Time is the cage, but time is also the freedom to move inside that cage.

There’s a stretch of coast on the Isle of Wight, where a bit of it falls into the sea every year, gets swept away. It’s all very soft sand. But it’s kind of multicolored, red and green. Slightly muted colors, but they’re unusual colors for sand. The cliff as it melts is like the edge of an ice cream, or a glacier just sliding down into the sea. And every summer I go back there and I walk along and I see how it’s changed from the year before. It’s what I call a “time coast.” In the course of my life, I’ve watched the whole thing retreat maybe 30 feet. I can see the old path. I can see where the steps were that my dad couldn’t walk down because he’d been wounded in the war, and he was angry because he felt vulnerable not being able to walk down these steps while his family was watching. And we’re saying, “It’s alright, dad.” He got really mad, because he felt he was looking stupid in front of us. And I can see the ghosts of the people who walked on the cliffs. And the cliffs are gone now.

It’s like a horizontal hourglass.

Yeah. A horizontal hourglass. I’ve walked along there looking at time since I was 12 or whatever. I may even have my ashes chucked into the sea there. Well, that might be a bit too obvious.

YouTube It

This clip, from director Jonathan Demme’s 1998 concert film Storefront Hitchcock, features a solo performance of “Airscape,” a track from Robyn Hitchcock and the Egyptians’ 1986 album, Element of Light. The performance begins with Hitchcock playing an E–A–B–A chord progression, with each chord using the open B and high-E strings to create a hypnotic, droning effect. At 5:08, he kicks on the overdrive, and plays a trippy instrumental passage that begins with a droning open D string. It’s a fine example of Hitchcock’s unique guitar approach, eschewing typical rock-god histrionics in favor of a thoughtful, angular style that’s more about creating a soundscape than showing off.

Photo by Reid Rolls

Studio Spangle: Brendan Benson on Recording Robyn Hitchcock

Rock fans may know Brendan Benson as a member of the Raconteurs, as a singer-songwriter in his own right, or for his label Readymade Records, but he’s also a prolific producer and engineer. He coproduced both Raconteurs albums with Jack White, and he’s helmed records by the Greenhornes, Cory Chisel, and the Howlin’ Brothers, among others. We spoke with Benson about the making of Robyn Hitchcock’s eponymous new album.

How did your role as producer come about?

We started talking by email. I had this studio—the building it was in has since been torn down—it was this really great space. I got the idea in my head to make a record with Robyn. I thought, “How cool would that be to make a record that was more along the lines of the Soft Boys?” With that same arrangement: two electric guitars, bass and drums. I wasn’t interested in making a psychedelic folk record. Which I respect, and I love his solo work. But I especially like the Soft Boys stuff.

How long have you been a fan?

The Soft Boys were one of those life-changing bands for me—the sound of it, the strange guitar playing and harmonies. And the lyrics, equally as strange.

Do you remember what amps you used?

I did a lot with Supros. I have a collection, and so we used a Supro amp on a lot of tracks. I don’t know the model number. It was an old ’60s with blue Tolex, one 12" speaker, all original transformers. I think it has one 6L6. I’m guessing. Real simple. And an AC30 reissue, a handwired one.He was always saying he wanted “spangly” guitars, which I sort of had to decipher as best I could.

I’m guessing spanky and jangly together?

Yes. And he was also kind of hell-bent on not having acoustic guitars on the record, which posed a problem for me. The engineer in me, and the arranger in me, thought it could’ve helped. I wanted the spangle to come from the acoustic guitars. And he was more into the electric spangly thing.

He told me he used a Telecaster of yours.

That was built by Charles Whitfill, a guy in Kentucky who’s making some really cool guitars. It’s his “T” Style model, and the one Robyn used is made of swamp ash. Robyn also used a vintage Fender Tele of mine—I think it’s a ’72. It’s cool because it was painted this weird blue at the factory. I can’t remember what the color was called.

What mics did you use to record guitars?

A Miktek C7 combined with a RCA BK-5. That C7 is really great on guitars.

What are you up to these days?

I’m working on my own album. It’s about halfway done, but I’m going to start releasing songs from it. The first single should be out in May.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)