If you’re a fan of the Telecaster and live in New York City, you might have had the transcendent experience of witnessing Jim Campilongo, one of the instrument’s indisputable masters, in action on a Monday night. Every week Campilongo holds court at Rockwood Music Hall, leading a mostly instrumental trio with Chris Morrissey on bass and Josh Dion on drums, before a small but rapt audience.

Whether playing with Norah Jones, Bright Eyes, or Martha Wainwright, Campilongo is known as a sensitive and refined sideman, but at Rockwood, another side of his personality is on full display. In a mode of expression that Campilongo refers to as “free rock”—which is to say, gritty and high-energy, and flexible in structure—the guitarist stretches out much further than in other settings.

On one hand, Campilongo is really out there. He plugs straight into an old Fender Princeton amp and delivers a range of bizarre effects from this minimalist rig that lesser players could only get with a floor full of stompboxes. On the other hand, the music that Campilongo plays in his trio is deeply rooted in tradition. Employing hybrid picking, as many Tele players are inclined to do, he borrows from Western swing, country, and classic rock in equal amounts, and he makes the most astute connections between these different genres.

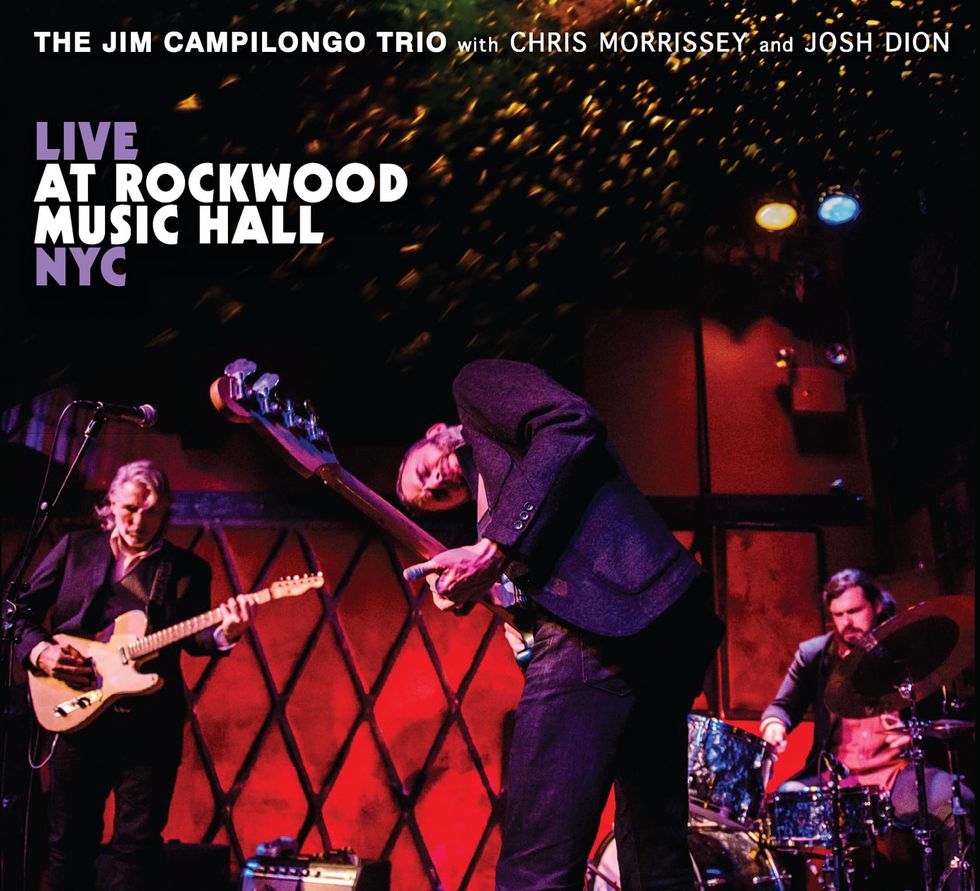

Campilongo’s new album, Live at Rockwood Music Hall NYC, includes some of the best performances from a year of the guitarist’s weekly residency, giving listeners not just a good sense of the depth and intensity of the trio’s live show, but a revelation of all that’s possible with just a Telecaster and a small tube amp.

Having just brewed himself a pot of coffee on a recent Sunday, Campilongo called from his home in Brooklyn and talked animatedly about how playing the Rockwood gig has enhanced his musicianship, how he creates some of his trademark effects on the Tele, what it’s like to jam with fellow guitar great Nels Cline, and why it’s important not to overthink things.

How has the Rockwood residency evolved over the years?

Well, it’s certainly made me a better player. In the beginning, Chris and Josh and I really walked a tightrope—if someone fell off, it was usually me—but those guys were so kind and supportive, any fear left me. If somebody goes to a galaxy no man has gone before by himself and doesn’t know how to get back, it’s usually greeted with support, somebody throwing you the downbeat, or simply laughing and later complimenting you. It’s looked at as bravery in the worst-case scenario. So I’ve become a way better improviser than I used to be.

We’re doing a Little Willies reunion, as a band with Norah Jones, Richard Julian, Dan Rieser, and Lee Alexander, and we haven’t played together for a number of years. In preparation I was listening to what I recorded a few years back, and there were some solos I worked out, melodic Duane Eddy–style solos. I started to learn them note-for-note, and then I was like, “You know, I don’t want to do this. I’m just going to play.”

My willingness to just play and take chances has grown considerably because of that weekly residency with Josh and Chris. It’s not easy, playing every week at the same place. And we all work hard at keeping the material new and not on autopilot. I mix up the sets, there’s always a new song every week, so there’s that, too.

TIDBIT: Campilongo selected the eight songs on his new album from roughly a year of shows, recorded and transferred to thumb drives, which he combed for the best performances.

Were only certain shows taped, and, if so, did you find yourself playing differently when you knew the recorder was on?

They’d miss a few here and there, but almost every show was recorded, and I totally would forget that. I so didn’t care because I had money in the bank and the main thing was just to go for it and play music with Josh and Chris. We weren’t in front of a studio at 10 a.m., hauling in drums, with the clock already ticking and the pressure on to do spirited versions of our music, as if we were playing in a nightclub.

How did you put the record together? Did it require extensive listening sessions?

I did it myself. They’d give me a thumb drive—one long song file—at the end of every show, and I would never listen to it, so I ended up having a bag full of them after about a year. I started moving through each track, and if there was a real winner, I’d splice it out and then mark what day it was. Then I’d see if I got another one that beat it, and that’s when it started driving me a little nuts. Some tracks eliminated themselves pretty quickly. Others, not so much. I could make three entire records of the bonus track, “Jim’s Blues.” I like so many of them.

How did you choose the version of “Jim’s Blues” that made it on the album?

It took a while to determine the winner, but the one I picked was one of the strongest performances. It was Chris’s favorite, and I really liked it as well. Like I said, there were other tunes that were much easier decisions. The track with Nels Cline that’s called “Cock and Bull Story” was an absolute no-brainer. Everyone totally went for it without thinking. We changed keys three or four times and went to such unexpected places. There is a bit of a fiery rapport at the end that I hope people find palatable. I think Nels’ playing on it is fantastic.

Check out these three lessons Campilongo created for PG back in 2012.

Campilongo is joined by fellow NYC-based guitarist Nels Cline (right), at Rockwood Music Hall. Cline plays on the new album's "Cock and Bull Story" and "There You Are." Photo by Dina Regine

How does a visit from Cline affect your playing?

Well, it’s just like playing with anyone, in some regards. I try to listen and make room for him and compliment him and support him. He does the same. Everything’s a bit renegotiated. It would be like getting a new roommate, right? It might be with your best friend and you get to see them, but you have to renegotiate the real estate.

The other thing is that Nels is simply a great musician. He’s real fiery and that’s a thrill. Sometimes I’ll play with someone, and I feel like their style is maybe more subdued. Then I feel like the proper etiquette is for me to be more subdued. You can’t come out like a bull in a china shop after somebody does an Eric Gale–style solo.

Nels is kind of a gunslinger, in the best way. He’s on your side, but he’s a gunslinger and so it’s really fun. It really pushes me and the band to the limit. I love what he does—especially when he channels John McLaughlin on “Cock and Bull.” A couple of times there’s this chromatic chaos and then he busts out of the gate.

That reminds me: I saw Nels a while back when I opened for Wilco in Chicago. He did this five-minute solo, and I swear I wanted to rip the chair out of the theater and throw it. I felt like a teenager. When I was a teenager I’d listen to Cream live, and I kind of wanted to break the furniture in my room. I rarely feel that way. So it’s exciting, to say the least, to have Nels come by.

You open “Jimi Jam” with one of your trademarks—some wild sounds courtesy of your lowered 6th string.

I’m glad you noticed that. I get a couple of sounds out of the Telecaster that nobody else has, that I know of. One is when I detune the low-E string to A, an octave lower than the open 5th string, hit a harmonic, and then push it up behind the nut. It really sounds like a Hendrix-ian vibrato or whammy-bar swell or something like that. Now granted, I’m doing it without an effect, on a guitar without a vibrato bar, but it does sound like a guitar with an effect and a vibrato bar.

Totally. It’s amazing what a world of sound you create—largely without pedals.

Well, thanks. I mean, people like Nels use pedals so creatively, and I really like that. But there’s the intimacy of being able to control the dynamics by my right-hand touch and just trying to get sounds from the guitar’s knobs. I mean, as soon as you use compression or something else, your vocabulary tends to be more forgiving of your right hand or your technique in general. You miss a relationship that’s literally hands-on.

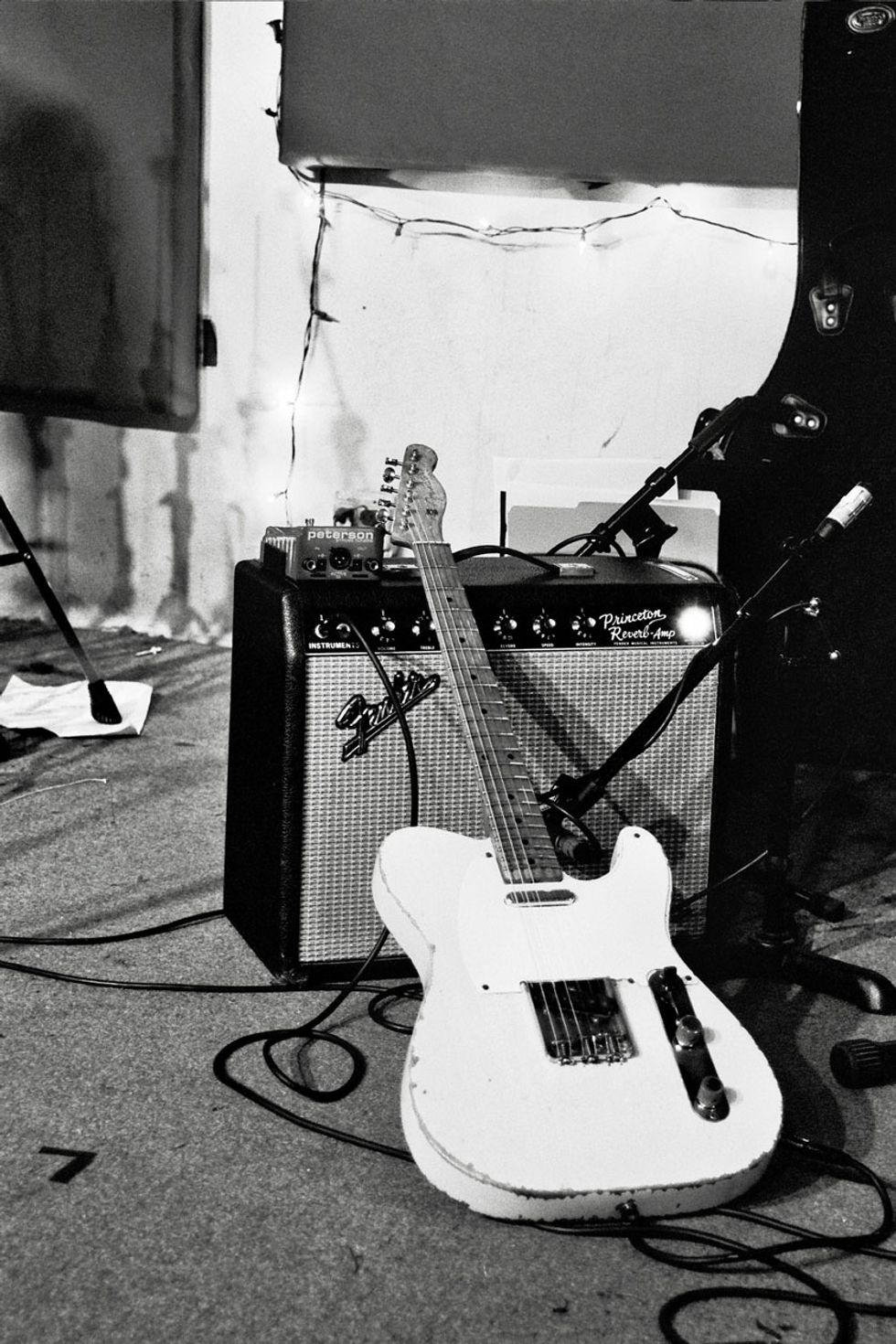

Guitars

1959 Fender Telecaster with late-1967 wiring

Fender Custom Shop 1959 Jim Campilongo Telecaster

Hahn Model C Jim Campilongo T-Style

Amps

Various blackface and silverface 1960s Fender Princeton Reverbs with Celestion G10 or Jensen C10N speakers

Effects

(used outside the trio)

JAM the Chill tremolo

JAM Delay Llama

JAM Red Muck fuzz/distortion

Strings and Picks

D'Addario EXL120 Nickel Wound Super Light (.009-.042)

Fender 358 Shape Classic Celluloid

Also, and maybe this is just me, but I feel like I connect with the audience more [by not using effects]. In the worst-case scenario—this is not like a supreme artist like Nels—I’ll see players looking down at their pedals, bending over dialing in their sound, and all that stuff. Then, surprisingly enough, this sound happens that sounds like an effect. I feel like audiences don’t connect with this sort of thing as much.

You’ve played a Telecaster for many years. Is your idiosyncratic approach to the guitar dictated by the Tele or is it the other way around?

On one hand, I just want an instrument that’s ready to go. I just want a hammer so I can make a doghouse. I don’t want to plug the hammer into a screwdriver and then plug that in and have to go get an adapter. So if I’m at home, I’ll often grab what’s closest to me. It might be my ’58 Gibson ES-225, and I mostly play it the same way I play the Telecaster.

On the other hand, I definitely love the sound of the Tele the best. I love that the tone control actually makes an impact. I played a ’62 Strat for about a decade, and I disengaged the tone control because it didn’t actually do too much. On a Telecaster, though, from 0 to 10—or even from 5 to 10—is a completely different universe. You can really find some nice and appropriate tones just by manipulating the guitar.

The other thing is that some of what I do in my trio has to be done on the Tele, some of the behind-the-nut bends. Like the thing I was just talking about: Detuning the low-E string, hitting a harmonic, and pushing it up.

Do you play your ’50s Telecaster through a Fender Princeton on the album?

Yeah, it’s a ’59 Telecaster. It’s a top loader. It’s the same guitar I’ve been playing for many years. I played it primarily, probably even exclusively, through a silverface Princeton with a Celestion G10 speaker.

I think I have six or seven Princetons, which might sound really decadent, but I don’t think I spent over $500 on any of them. I bought them around 2003, because I only had one blackface Princeton when I arrived in New York in 2002, and at one gig it conked out. At that point, Princetons weren’t as popular as other Fenders, and I thought, “They’re going to become popular because they’re really perfect amps.” They’re light. They have a great reverb and vibrato. It’s all in there. No fuss, no muss. You can turn ’em up and they sound good. Even though they’re only 12 watts, 99 percent of the time they had enough power for me. So I bought a whole bunch of them—even more than I have now.

Jim Campilongo, playing his top-loading 1959 Fender Telecaster, has a Monday night residency at New York City's Rockwood Music Hall that's become a mecca for guitarists and 6-string fans. It's also where his new album was recorded live. Photo by Manish Gosalia

How did you find them back then?

I’d just see one on eBay, or a friend would come over to the house and say, “Hey, I found a Princeton, and I’d go, “Let’s buy it.” I did this for about a year, and what ended up happening was that I could really only afford the time and expense of keeping two Princetons running at optimum level, where there’s no hum, the tubes are great, and the speaker’s robust and healthy.

I mean, these things, you need to spray money with a fire hose on them. They’re 50- to 60-year-old amps, and I play them on 10. The shelf life is usually about six months and then it’s time to go drop them off. Since the early 2000s, I’ve always had two that are in really fine working order and then all the others are good. They’re fine by anybody’s standards, but they’re just not ready for the Indianapolis 500.

Hahn just released the Model C Campilongo T-style guitar. How does it compare to your ’59 and Fender Custom Shop Teles, and have you played it yet at Rockwood?

We worked on it for months, but the prototype just came about a week ago [mid-December], and I played it in a bar with some musician friends at a Christmas party. I love the guitar. The neck is really comfortable, the body is light, and it really sounds great cranked! Unlike the Fender Campilongo signature guitar, we were basically trying to make a guitar I liked without any preconceptions, and we also wanted to make it affordable. Chihoe Hahn bent over backwards to offer it at a much lower price than his usual boutique-level guitars. It’s made in the U.S. and priced at $1,495, including a gig bag and shipping.

Campilongo's primary tools of expression are simple: his '59 Tele or one of his Fender or Hahn signature models, and one of his vintage Fender Princeton Reverb amps, which sport Celestion G10 or Jensen C10N speakers. Photo by Arithi Krishnaswami

Getting back to the album, “Big Bill” is a great rhythm-changes tune. Talk a little about your jazz background.

A long time ago I played with Jimmy Rivers, who was a really great guitarist. He made an album called Brisbane Bop, and it was a big influence on me. I did a pilgrimage to meet him and see him play when he was in his 70s. I was in my early 30s and still a pretty young guy, and he was super nice and was very generous with his advice.

Jimmy could just rip over rhythm changes [a reference to the chord progression from George Gershwin’s “I’ve Got Rhythm” that’s reworked into many jazz classics]. I got together with him a couple of times and showed him all the tunes that were giving me problems. He’d show me a new way of looking at them, by eliminating, like, two-thirds of the chords.

How so?

At the time, I was struggling through the Real Book [a compilation of lead sheets for hundreds of standards and jazz compositions], with so many tunes packed densely with chords. Jimmy could look and a complicated progression and see the bigger picture. For example, he’d say, “No, it’s just C and A7.” When we got to rhythm changes, for the A section, he said, “Just think I–V.” I mean, if you’re in Bb, then you can just play Bb and F7 chords throughout the A section, which is three-fourths of the song.

On “Big Bill,” I’m sometimes thinking Bb chord to B, which is the tritone substitution for F7—another concept I learned from Jimmy. But I’m playing Ramones-style chords to add an interesting twist. I’m sure there’s not enough room for me to go on about what I learned from Jimmy. It could take up the whole magazine [laughs].

It’s such an important concept—seeing the big picture. What else did you learn from Rivers?

Another important thing I got from Jimmy is that when I asked him how he put his style together, he told me that this was simply from learning to play “(Up a) Lazy River,” the Hoagy Carmichael tune, in all 12 keys. I did that and realized, “Oh yeah, this sounds like Jimmy.” I learned those lines and transposed them and started using them as the foundation for my improv. It really helped me learn to play over changes without overthinking things. That’s the ultimate goal—to not think too much.

On a typical Monday at New York City's Rockwood Music Hall, Jim Campilongo, Chris Morrissey, and Josh Dion rip through "Big Bill," replete with droning bombs, atonal runs, and—at the two-minute mark—some of the wailing behind-the-nut bends Campilongo cultivated from another Tele master, Roy Buchanan.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.