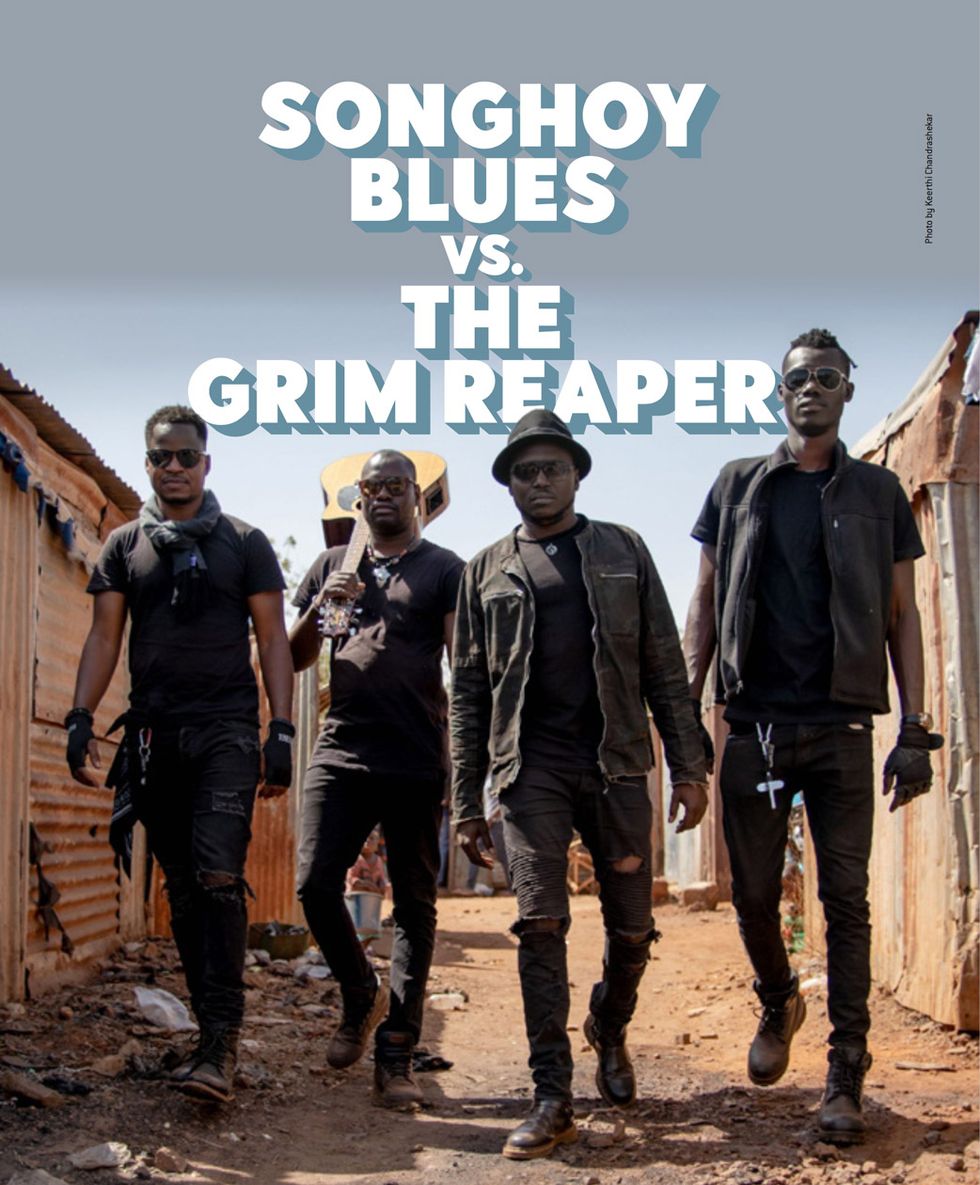

Following a violent civil war and a failed military coup, and under the increasingly oppressive control of the Ansar Dine Islamist regime—which had imposed Sharia law and outlawed music in all forms in Northern Mali—guitarist Garba Touré left his home in Diré (a small town on the Niger River in the North) for the country’s capitol, Bamako, with all of his worldly belongings in a bag and his guitar on his back.

There, Touré met the men that would become his bandmates in Songhoy Blues—fellow refugees from the North whose lives were similarly upended by the conflict. The group forged a connection performing the traditional music of the Songhoy people for their fellow refugees as a salve and source of comfort, but eventually the band developed its own unique sound: a revved-up fusion of traditional Songhoy melodies and grooves with elements of the Western blues and rock the young men shared a fondness for.

Songhoy Blues’ music provided an ideal space for the four refugees to sing about the atrocities that had ravaged their homeland, and an outlet for cutting songs of resistance. But they also sang of hope for the future of their native Northern Mali and good times to come. In September 2013, the group was discovered playing in a Bamako nightclub by French producer Marc-Antoine Moreau, who, along with Damon Albarn of Blur and Gorillaz fame, helped Songhoy Blues record a debut LP, 2015’s Music In Exile,with Yeah Yeah Yeahs guitarist Nick Zinner and Moreau co-producing under the aegis of the Africa Express cultural collaboration non-profit.

The award-winning documentary They Will Have To Kill Us First tells the band’s harrowing and uplifting origin story in brilliant detail and is well worth a screening. And while the conflict sadly continues to smolder in Northern Mali, a lot has changed for Garba Touré and Songhoy Blues since being plucked from the sweaty clubs of Bamako.

On the steam of Music In Exile, Songhoy Blues became an international sensation, touring the world and playing major festivals like Glastonbury, opening for artists like Alabama Shakes and Julian Casablancas, and releasing a critically-acclaimed 2017 sophomore album, Résistance, which boasts a track featuring Iggy Pop.

At its core, Songhoy Blues’ ever-evolving take on what’s known as “desert blues” is a pure expression of rock ’n’ roll’s exuberance and youthful brashness but channeled through a radically different musical vocabulary than what most Western ears are familiar with. Touré’s virtuosic guitar work is the cornerstone of Songhoy Blues’ unique sound … and it’s also painfully cool. His playing is a blend of stuttering, percussive rhythm work, fluid and undulating melodies that fold over themselves, and searing blasts of Saharan shred that take rock-guitar heroics and twist them up into something altogether unique. While Garba Touré is deeply steeped in the Songhoy guitar tradition that once made fellow Northerner Ali Farka Touré a breakout star, Garba’s style has been tweaked and supercharged by the influence of Western greats like Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan. (No relation by the way. Touré is an extremely common surname in West Africa, though Garba’s father, Oumar Touré, played guitar and congas in Ali Farka’s band.)

With their new album, Optimisme, Songhoy Blues’ sound is fully-realized—tempered and focused by years of international touring. Recorded in a whirlwind six days at Brooklyn’s Strange Weather Studio under the care of prodigious guitarist, producer, and guitar culture gourmand Matt Sweeney (Chavez, Johnny Cash, Iggy Pop, and host/creator of the fabulous Guitar Moves web series) and engineer Daniel Schlett (the War On Drugs, Modest Mouse), Optimisme is Songhoy Blues’ most cohesive and incendiary statement, and a true point of arrival.

The album features the band’s first song written in English: an uplifting anthem of hope titled “Worry,” which serves as a spot of positivity in a set that’s chiefly concerned with the heaviest realities of war-torn Mali.

There’s a pathos and sincerity to Optimisme that is generally lacking in Western rock ’n’ roll these days, and global recognition has done nothing to blunt Songhoy Blues’ dedication to contributing to the resistance through its music. Optimisme’s songs discuss gravely serious matters like forced marriage (“Gabi”) and the exhausting struggle of the revolution (“Barre”), yet these songs are all still absolutely raucous, groove-laden rave-ups that sound like nothing else. Especially the fuzzed-out barnstormer “Badala.”

Unmistakably, Optimisme charts territory further beyond the margins of traditional Songhoy guitar music, beyond cheap exotica, and beyond the novelty Western music fans often make of guitar music from faraway lands—pushing a traditional culture into a new era, as Ali Farka Touré once did with his own exploration of blues. At a time when blues-based rock ’n’ roll has eaten its own tail, Optimisme reimagines guitar rock by way of the very West African cradle from which it first came.

Premier Guitar spoke with Garba Touré and Matt Sweeney by phone—with a little translation assistance from the band’s tour manger, Matt Taylor, on some follow-up questions for Touré—to get the inside story of crafting Songhoy Blues’ vibrant new album. Despite the miles and cultural disparities between New York City and Bamako, the bond between these kindred guitarmen is strong, and the mutual respect they share palpable. Touré and Sweeney went deep on the writing and recording process, did a deep dive on Touré’s background and philosophy as a guitarist, spoke about the minimalist gear used to track Optimisme, and discussed why an artist with Sweeney’s remarkable resume has found himself so deeply under the spell of desert blues.

Could you tell me how Songhoy Blues approaches writing songs and if that process changed at all on Optimisme?

Garba Touré: We always write songs together. Usually someone comes in with a subject to sing about or I’ll come in with a guitar riff, but anyone in the band can propose an idea to start with. Once we get it as a band, everyone’s input is heard and we all add our ideas. Our songs can come from many places and any instrument, but we build them together all the time. For this album, after we wrote the songs and did demos, we listened to them with Matt [Sweeney], and he helped us to build each track and make the songs sound their best.

Matt Sweeney: West African musicians don’t have the obsession with listening to albums like Westerners do. Music is this living, breathing thing in Tuareg and Songhoy cultures. There isn’t this primacy with the album as an art form, so what’s cool about working with Songhoy Blues is that while these guys are usually really about music in-the-moment, on this record they were very aware they were making an album, and that can be a bigger thing than just capturing songs.

TIDBIT: In a true cross-cultural collaboration, the new Songhoy Blues album was recorded in Brooklyn with a production team that made its bones in alt-rock, but Optimisme is rooted firmly in Mali’s Songhoy tradition—and juiced by fuzztone guitar.

Bamako is a place where people like to party and it has a sophisticated nightlife, so these guys are really cool and they know what it’s like to go out and drink beer in a room with music and action. The overarching concept that tied this record together was that we all wanted it to feel like Songhoy Blues taking us out for a night in Bamako, with each song being like walking into a different club or alleyway. I wanted it to feel sweaty, live, and exciting. And a little dangerous. They were totally with that idea. So with that concept in mind, we were able to start thinking of it as an album, rather than just a few songs being tracked, and the performances were definitely better for it. We had a conversation about increasing all the tempos and focused a lot on how we could make each song super-exciting and make this record feel super hyped-up. They had such great ideas to that end.

How did you track to get that hyped-up feel?

Sweeney: Live, for the most part. I literally got off a plane and went straight to the studio on day one, and the guys had been working all day. The one thing that they had put down was “Badala,” which really blew my mind and set the tone for the record. The guys would show me the song, I’d make suggestions, and we’d take things apart and put them back together as a team.

We’d usually take like an hour to rearrange a song and then cut it live with a scratch vocal, then we went back to add real lead vocals, group vocals, and we did a day or two of small overdubs and Garba shredding. They work really well together and are super-efficient. We were working really hard and only had six days, but we never got hung up on anything. For example “Worry” came in as this kind of lope-y thing that had like a reggae feel. And that one was like, “Okay! Great lyrics and melody, but what can we do to better support them?” Garba came up with that guitar riff literally on the spot, and I went “What the fuck?! That’s insane!” and then we had it.

We really had a lot of fun turning these songs inside out in a very spontaneous way, but then recording them quickly to capture that spark. The same kind of thing played out on “Pour Toi,” with that big tempo change in the middle. We worked out how to maximize the song’s energy as a team. There was some thought put into how these songs would feel to play live, and “Pour Toi” is a good example of the live consideration changing a song’s vibe for the better, with that big scene/tempo change.

Touré: When we built “Pour Toi,” it started with that first part and we decided it needed a second part with much more energy. We built that bridge/second part with Matt, and had two parts to choose from for the second half, and we went for the higher energy one. Recording in a great studio like Strange Weather was such a good experience for us. Daniel Schlett was very good to work with, and a great sound engineer, and really knew how to get the sounds we wanted. Matt was really the maestro. He was there early every morning to really help us create a great album.

At home in Bamako, Mali, Garba Touré practices riffs on an American-made Fender Stratocaster, but when he travels he rents guitars along the band’s touring route. Photo by Omar Touré

Matt, you’ve been a champion of desert blues and West African guitarists for years now. You’ve worked with Mdou Moctar, Tinariwen, and now Songhoy Blues. As a guitarist yourself, what is it that makes Garba’s playing so compelling?

Sweeney: I don’t see how you can be interested in guitar music and not like West African players. Objectively, if you like the sound of electric guitars, I think that West African guys have really got it fuckin’ nailed and do something with the instrument that’s as exciting as anything that’s ever happened on an electric guitar, and completely unique relative to what most guitar fans know about these days.

It’s interesting, because a lot of white dudes like to play rock guitar, and I think it’s really important that people consider where electric rock guitar really came from and how it got here. You could write a book about how blues-based rock guitar has become this bastion for white dudes to hide out in, but it’s also in a weird place because its vocabulary—blues-rock or whatever—is kind of played out now. I don’t know that anyone’s done something truly new with it since Eddie Van Halen. When you hear Songhoy Blues, while it’s immediately recognizable as rock guitar and you’ve heard these notes and sounds before, most have never heard them used the way Garba plays. It’s upside down and backwards and completely unique. It’s also got the same appeal that pre-war blues has, in that there’s this sound of resistance in it. Desert blues and pre-war American blues both make something beautiful out of expressing human struggles. And Garba Touré is probably the best example of a West African guitarist that someone with rock tastes typically hears and goes, “Holy shit! What is this?!” Garba’s approach to guitar is just endlessly fascinating to me. Also, when these dudes listen to rock music, they’re picking up on different things in it than we are, and vice versa for us with West African guitar stuff. The things they take from rock music are more of its energy than its vocabulary.

Garba, tell me about working with Matt. Can you compare it to your experience recording with Nick Zinner back in 2015?

Touré: With Nick Zinner, it was for our first album and we really had no idea about the world or recording. Nick found us when we were still very much local musicians—before we’d ever played in any other country outside of Mali. Nick was very, very helpful with our first album, but we were new to recording. With Matt, we’ve been touring for five years, we’ve met loads of big bands, and we’ve discovered a lot of different kinds of music around the world in that time. Matt is a great musician and was really good with ideas and suggestions for making our songs better, arrangements, but Matt never wanted to really change what we would bring him or to bring us something new of his own—he just wanted to help us succeed in getting the best out of what we brought him. Matt and Daniel really helped me to get the sounds I wanted on this album. I know which kind of sound I want and it always takes some pedals. I really love the sounds we got on “Badala,” “Worry,” and “Bon Bon.”

Garba, I hear a lot more rock ’n’ roll and American blues on Optimisme than on past Songhoy Blues albums. Were you listening to more of that stuff when writing these songs? And can you tell me about your relationship with Western guitarists like Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan?

Touré: I really love American bluesmen like Gary Clark Jr. I love his style of guitar. Joe Bonamassa is one I love, too. And Eric Gales … loads of the big American guitar players. Anyone with their own style. Stevie Ray Vaughan is my favorite blues guitar player forever.

To me, Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan are such legends of guitar. I listened to Jimi Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan and I loved their songs before I even played guitar myself, so when I first began to play, I tried myself to play their songs. They were my favorite guitar players and this was before we had the internet, so I just listened to their songs and didn’t have any images of them. I really love “Purple Haze” by Hendrix, and “Superstition” and “Mary Had a Little Lamb” by Stevie Ray Vaughan. I also really love Nirvana and anything distorted like them.

On the other side of your sound, can you tell me about the traditional guitar players from Mali that influenced your playing?

Touré: Ali Farka Touré was really the big legend guitar player of the Songhoy community. When we were young, he was the first big guitar player in our community and was very important. My father, Oumar Touré [not to be confused with Songhoy Blues’ bassist, who shares that name], was a guitar player that played with Ali Farka, too. Gaoussou Konate and Albakey Cissé didn’t have the chance to have international careers but were very important Songhoy guitar players. Sadly, both are now dead. But Ali Farka was the only guy that had the songs that made the world discover him, and he’s still the legend of legends of Songhoy players.

Did you learn much on guitar from your father?

Touré: When I was a kid, my dad didn’t want me to play the guitar. He just wanted me to study. One day, he listened to me play and he knew there was nothing else I could do but play guitar. It would be impossible for me to give up the guitar. I learned a lot from my father. At first he didn’t want me to touch his guitar, but eventually he helped me a lot to correct my notes and figure out where the half notes go and such—especially in the traditional styles.

A lot of American blues players are focused on preserving its history and keeping the blues tradition alive. Is there a similar concern with Songhoy players, especially considering how Songhoy Blues mixes traditional sounds with Western stuff?

Touré: It’s different for our generation than it was for Ali Farka Touré’s. For them, they thought it was better to keep playing traditional Malian music, which has been around for a couple hundred years. Ali Farka’s generation didn’t intermix that music with other styles, really, and most of that generation played those songs on traditional instruments, so when Ali Farka played traditional music on an instrument like the guitar, it was a new thing and very modern for us at the time. For us, we’re a new generation and we have to give it another face and show a new way for Songhoy music to live on. We can’t keep playing the music like the last generation, and we have to connect our music with the rest of the world.

Matt, you said working with Songhoy Blues was really easy and that they’re really efficient in the studio. Do you think part of that easy working dynamic comes from them not taking the opportunity for granted and coming from a background of struggle?

Sweeney: I really do. I also think it’s important for people that are spending their money on these modern blues albums that really don’t add anything to the conversation to check out some other stuff. If you like music that’s blues-based and rock-based, it’s all based in African music. That music is based in a personal struggle, and if you want to have your mind blown by something that’s rooted in an ancient style, but equally fresh and new, Songhoy Blues is as real as it gets. There’s also this ugly attitude about things that come from Africa being sort of disposable in the eyes of a lot of idiots. Hopefully this record changes that and opens the world up to Songhoy’s thing. And I’m saying all of this out of love for the pursuit of excellence on the guitar and out of a love for guitar magazine culture. Garba and I sit on WhatsApp sending each other riffs to figure out all the time, and we really share the same passion for the instrument filtered through different experiences. The truth is this guy grew up around Ali Farka Touré and some of the illest goddamned guitar playing ever. Garba’s steeped in a deep, really rich guitar playing tradition that he doesn’t even have to think about! It’s almost second nature.

Guitars

Fender ’60s Jazzmaster Reissue

1967 Gibson Melody Maker SG

Amps

Early ’70s Fender Pro Reverb

’60s Supro Model 24

Effects

Echopark F-1 Germanium Fuzz

Echopark FQ12 Range-Bastard

Vintage Mu-Tron Bi-Phase

Nuñez Amplification Dual Range Boost

Strings and Picks

La Bella flatwounds in various gauges

Various picks

Garba, when Songhoy Blues made its first album, you had just a Yamaha electric guitar, but it seems like you’ve got a different guitar in every video these days. What were the main ones you used on this album?

Touré: That Yamaha wasn’t a very professional guitar, but I had no money to buy a new guitar then, so it was my only one. You see me using a lot of guitars because, when we tour the world, I always hire guitars. I like Gibson SGs or Fender Jazzmasters and Stratocasters. I usually tour with rented guitars. I have a Fender Jazzmaster of my own now and it’s good for me. It sounds warmer than a lot of other guitars, but sometimes onstage I like more bass in my sound than it has, and that’s why I like Gibson SGs. I used a lot of different guitars in the studio on this album, but my favorite was that SG.

What were the main guitars, amps, and effects used to shape the tones on the album?

Sweeney: It was mostly a Fender Pro Reverb and a vintage Supro. The things that made a huge difference were these two pedals by Echopark: their F-1 Germanium Fuzz and FQ12 Dual Range-Bastard. I use that F-1 fuzz on every record I make. The FQ12 is more of a preamp with a bunch of filters, and I had that on almost all the time on this record to give the guitar a little poke. We also used the fuck out of a vintage Mu-Tron Bi-Phase. I used that thing constantly. Garba mostly used a 1967 Gibson Melody Maker SG that belongs to the studio.

Touré: “Gabi” was that Gibson SG. That’s actually a very traditional song, too.

Garba, are you in standard tuning most of the time or are you using any unique ones?

Touré: Yeah, most of the time, but I also use a traditional Malian one where you tune the low-E string differently. You hear that tuning on “Gabi.” It’s just bottom E tuned up to G. G–A–D–G–B–E. It’s an old traditional method, mostly used in the North of Mali by Songhoy people.

Garba, we interviewed you in 2015 when the band’s debut LP had just come out. How have you changed as a guitarist since then?

Touré: I think I’ve progressed a lot since then. I’ve done a lot of travelling and I’ve met a lot of different kinds of guitar players over the years, and I always work hard to discover new things on the guitar. All of those things have made me more professional-sounding than before we started to do international tours. There are a lot of new players I like and there have been many times when we’ve played big festivals and shared the stage with great guitarists, and you always try to keep their riffs and style in your mind and one day you might work with them, so it’s helpful to know what they do as guitar players, but also to develop the style you’ve already got and be true to yourself.

Matt, I’ve watched you hone in on what a guitarist’s picking hand is doing on so many of your Guitar Moves clips, and Garba’s right hand moves in a wildly unique way. What’s the key to his rhythm style?

Sweeney: It’s fucking hard! I’ve spent a lot of time playing guitar and trading riffs with Garba, and the one thing I’ve noticed is there’s this choked and percussive quality to a lot of African guitar playing that’s so cool. In a lot of rock guitar playing, you’re going for the big, long, screaming note. That’s not really a part of most of the African guitar stuff that I’ve encountered. It’s a lot of choked, almost dead notes. It really is a completely different way of making the guitar sound really fucking good! If anything, it just shows again how varied and endlessly expressive the guitar can be. A good guitar player should be able to make any guitar sound good, but with the African desert blues stuff, because of that percussive style, it seems like you can make really any guitar sound really good. Pre-war blues had the same quality, where it was about making the most out of what you’ve got, and usually using a shitty instrument because that’s what’s available.

Garba, are your solos on Optimisme improvised or composed?

Touré: I improvise every solo both onstage and in the studio. I always play as naturally as possible in the studio, like we’re onstage, and sometimes I’ll do two or three takes and we’ll choose between them, but a lot of the time when we recorded this album, I’d play just one solo take and everyone would say “yes!” and that would be the one we’d keep.

On “Assadja,” are both of the guitar parts that weave together in the verse you?

Touré: Those are both my guitar parts. I played all the guitars on that song. That’s a very traditional song, and the second part of it is part of a very traditional Malian song, but we turned it into a new song by playing it much faster than the original version.

“Worry” has such a great message. With all the struggles people are experiencing these days, do you have any advice for musicians that feel defeated right now, Garba?

Touré: Try to stay safe and just keep working. One day this will all be over and all musicians are going to have a chance to make music again. You just have to be patient and stay safe at home!

Matt, you’ve worked on a lot of records by artists from a really wide range of genres, but I imagine working with guys that have been through what Songhoy Blues has, and creating music covering the heavy topics on Optimisme, is a unique experience.

Sweeney: Beyond just wanting the record to sound cool, all of these songs are really important and these lyrics are really important, so I felt extremely compelled to not fuck this one up. It’s an opportunity to work with a band that I think is truly great, and I just wanted to help them get the most out of the record for them, really. Part of that is also knowing how and when to stay out of the way. It’s humbling working with guys that are this good, but also guys who have been through that much shit. What they’re doing is really important to them in a way that I can’t even pretend to understand. And the things that they’re saying in some of these songs can get them fucking killed where they live. It’s really heavy. Beyond that, they’re still a bunch of rockin’-ass dudes! They want to have a good time and they want the music to feel that way, too. They don’t take this for granted, and it was such a pleasure to work with these guys on a human level, and the work was serious, but they’re fun as shit to hang out with! We all agree on what rocks and what’s exciting in music, and how often do you get to really reaffirm those things with other people? Especially from such a different walk of life. It just shows how universal those things are.

Watch Garba Touré lay into his fuzz pedal for a solo that starts at the 1:43 mark, and then snap back into a clean rhythm that would make Jimmy Nolen proud, on Songhoy Blues’ “Bamako.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)