Editor’s note: Glenn Branca, the composer and guitar innovator, died on Sunday, May 13, from throat cancer. Branca was known for creating storm-roiled seas of 6-string sound, conjured with alternate tunings, repetition, volume, and his brilliant harmonic explorations. Guitarist and composer Elliott Sharp, who knew Branca as a fellow member of New York City’s avant-garde and experimental music scene, shares his memories and impressions of Branca in this tribute.

The notorious Mudd Club, downtown N.Y.C., October 1979. On a foray to the City from the wilds of western Massachusetts, I was anxious to scope out possibilities in the Big Ashtray before making my move. I had been resonating deeply with the “no wave” scene, as personified by the Contortions, Lydia Lunch, Mars, and DNA—all represented on the Brian Eno-produced compilation No New York.

Glenn Branca was a name mentioned in the same breath, and his band with Barbara Ess and Christine Hahn, the Static, were playing on this night. Past the surly doorman into the dull gray box of a club, booming sound system, Jean-Michel Basquiat dancing quietly in a corner, skinny ties on the guys, dark shades on the girls … new wave bohemian heaven. With no fanfare, the Static took the stage, barely illuminated by dirty fluorescent bulbs and tired spotlights. Glenn sported a Telecaster. The band was bone-crushingly loud. It was not hi-fi loud or disco loud; it was factory loud, B-52 loud, as befitting the space. The guitar was in an open tuning, as Glenn’s hand shapes were unfamiliar, grasping for the dark and ringing chords. Lots of minor seconds in there. Over a drum pulse reminiscent of the Velvet Underground’s Moe Tucker, their songs rang out classic themes: “My Relationship,” “Don’t Let Me Stop You,” “Fuck Yourself.” The guitars meshed and clashed, producing a throbbing drone and bright ringing. Suddenly, they would clarify into a two-chord stomp, sounding like the Stooges or some of the Seeds’ heavier moments. (For a free download of the Static’s “My Relationship”/”Don’t Let Me Stop You” single, click here.)

Shortly after that and now in the City, I was hungry for work. Glenn had posted a small ad in The Village Voice seeking musicians for a larger ensemble consisting of all guitars plus drums. I gave him a call and his initially gruff demeanor began to thaw as we spoke about shared tastes in music: Messiaen, Penderecki. Then he asked, “Do you play jazz?” I answered that I did, but I was not a jazz guitarist. His response: “Forget it!” And he hung up! We laughed about that many years later.

Glenn’s tough reputation was amplified by his stage demeanor: possessed by the music, chain-smoking cigarettes down to the ash, glaring with eyes bulging, screaming even when his mouth was closed. I caught one of the earliest gigs of his expanded guitar group at Tier 3, an important little dive in Tribeca. The music was certainly loud, repetitive, always transcendent. The guitars were in open tunings, lots of unisons and octaves, cheap Teiscos, single-coil pickups. The strummed attacks created a dense froth of white noise, while the vibrating strings yielded tsunami waves of harmonics, overtones filling the air.

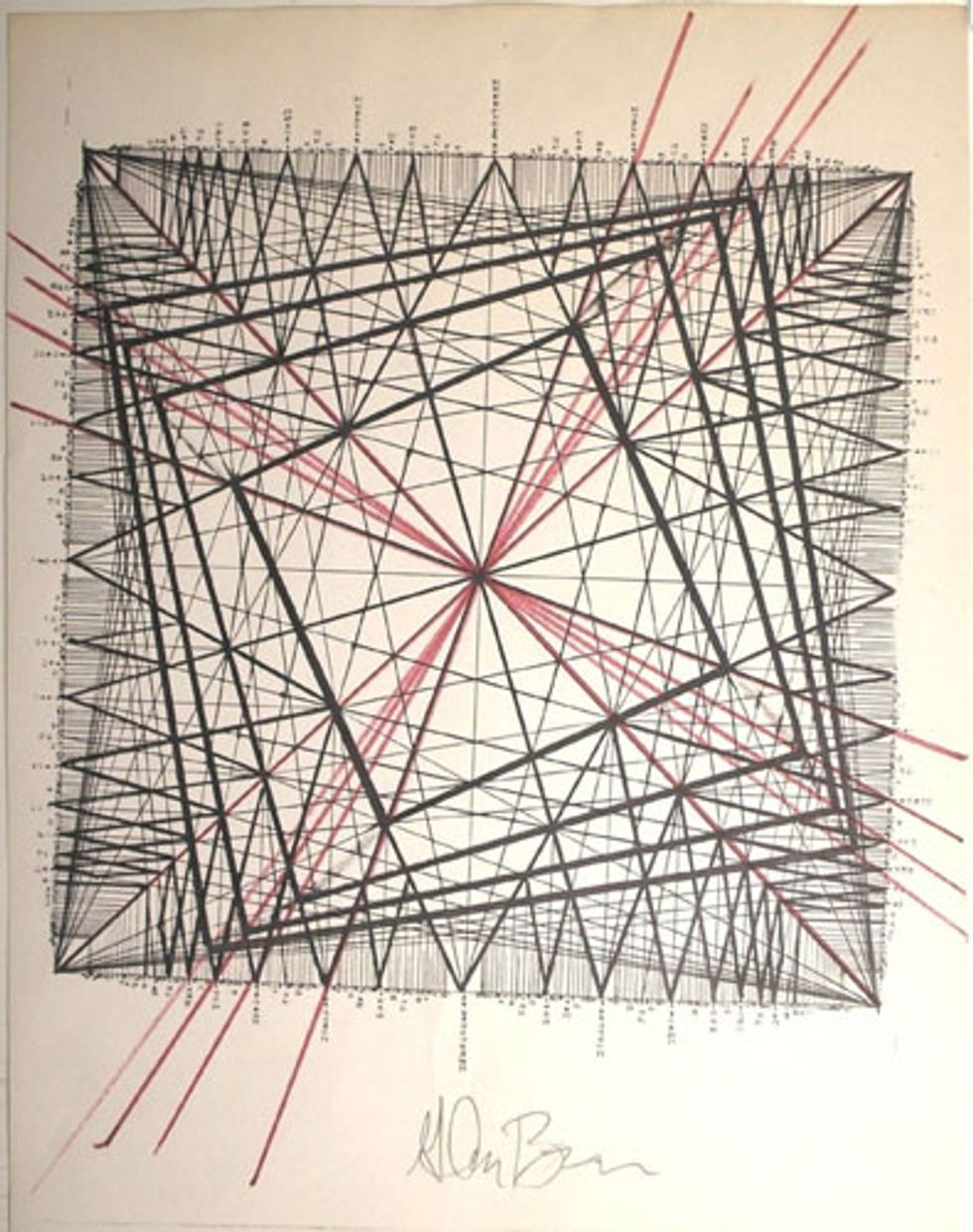

Using mathematics and drafting techniques, Glenn created delicate but powerful visualizations of the structure of his music. These “scores” display the relationship between acoustic principles and their manifestation via loud guitars. Photo courtesy of the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery at Florida Southwestern State College.

The music made its intentions clear. This was not entertainment. This was not clever new-wave songs. This was certainly not jazz. Though the musicians all had the air of rockers, it was definitely not rock ’n’ roll. This was music for consciousness razing—music for falling into a gray void and emerging on the other side, transformed.

In 1981, I was part of an orchestra of nine bassists opening for Glenn’s ensemble, who played one long piece, deafeningly loud. As the music neared its extended climax, a startling physical manifestation to the sound was revealed. The guitars flailed and the overtones rang. When the drummer hit his kick, the air literally shattered, vibrations from the heterodyning causing sum-and difference-tone effects to fill the physical space down to the molecular level. One could see the sound shake!

One of Branca’s guitars displaying intriguing custom fret positioning, for maximum harmonic generation in his alternate tunings, and a colorful PC board housing the controls. Photo courtesy of the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery at Florida Southwestern State College.

That night was the first time Glenn and I had spoken since that initial phone call, exchanging thoughts with our ideas converging around the notion of the alteration of consciousness through psychoacoustics—the power of the “ghost instruments” produced as results of the volume and the tunings. In 1982, watching his group perform his second symphony, The Peak of the Sacred, at St. Mark’s Church in the East Village with percussionist Z’ev as featured guest soloist, brought home with finality the notion of this work as ritual, esthetics subsumed to the task at hand, shifting the parameters of perception. This wasn’t just a bunch of notes! Glenn’s group served both as the real-time laboratory for the intersection of his music and philosophic endeavors, and as the breeding ground for musicians who would go on to found Sonic Youth, Swans, Rat at Rat R, and more.

The world of science fiction underwent a positive sea change after the publication in 1984 of William Gibson’s Neuromancer. In the ’80s, I found out that Glenn was also a rabid cyberpunk fan and was distributing various books and reprinting rarities in one-off compilations. We hadn’t been in contact in some time and now our conversations were about the latest output of Jack Womack and K.W. Jeter, or obscure writers whose work was being hand-printed in English fanzines.

Author Mark Dery had the idea to bring the two of us together for dinner and publish the conversation in the vivid but short-lived cyberculture magazine Mondo 2000 as “We Are the Reality of the Cyberpunk Fantasy.” Glenn was a surprisingly adept chef and, over perfectly barbecued shrimp and perhaps too much sauvignon blanc, we discussed the nature of consciousness, the state of artificial intelligence, and the merits of alternate-tuning systems. A fine time!

Though Glenn was well known for his guitar orchestras, not many people knew of his visual work. Using mathematics and drafting techniques, Glenn created delicate but powerful visualizations of the structure of his music, clearly displaying the relationship between the acoustic principles and their manifestation via loud guitars. These works are both illustration of the nuts-and-bolts hidden in the music as well as the Platonic ideal of sound crystallized, then committed to paper. If Glenn were reading this piece, he’d probably let loose with a sarcastic obscenity, but the fact is that Branca lived the passion that he put into his sound. He lived it as a musician, thinker, artist, and human of great generosity and kindness.

YouTube It

Glenn Branca premiered his “Symphony No. 16 (Orgasm),” composed for 100 electric guitars, basses, and drums, in Paris in February 2015. Here, he conducts its first movement.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)