"I consider it a real blessing having learned the guitar through the blues medium," says Robben Ford. "I then developed a great love for jazz and, in particular, the tenor saxophone. Those guys—or the guys that I like, I should say—are all very vocal players. They're singers. Miles Davis's trumpet as well is the most brilliant example of a trumpet player using his horn as a voice. It's very much related to speech. Sometimes you speak softly. Sometimes you just groove along. Sometimes you yell. You're always trying to say something as opposed to play something."

Robben Ford's musical conversations date back to the early 1970s and include work with artists as disparate as Joni Mitchell, George Harrison, Miles Davis, the Yellowjackets, and Charlie Musselwhite. He's also released more than 30 albums as a leader, with most featuring his songwriting and vocals. However, like many things these days, change is in the air, and his recently released Pure is an all-instrumental album. It's the first time he's done that since Tiger Walk in 1997.

Pure

Ford's playing is a unique hybrid style that incorporates the nuance and sensibilities of the blues with the harmonic complexity of jazz. It's an approach that sounds intuitive and obvious in his hands, and on Pure, he takes advantage of the instrumental setting to showcase those different sides of his musical personality.

Pure's roots date back to 2017, when Ford relocated to Nashville. After years on the road, he was looking for a community with a vibrant music scene. He wanted a place where he could gig regularly with local players, focus on producing albums for other artists, and—for someone who's basically been a road warrior since the early 1970s—somewhat settle down.

"I've always been trying to find it on the guitar as opposed to with an effect."

By early 2020, Ford had racked up a number of production credits and was knee-deep in instrumental projects with people like saxophonist Bill Evans, pedal-steel guitarist Paul Franklin, and guitarist John Jorgenson. But then the world came to a screeching halt, and all that work was put on hold.

Except his psyche was still in a very instrumental zone, because that's what he was busy with when the work dried up. "Ever since Tiger Walk, I've basically devoted myself to really learning how to write a good song and to deliver it on the bandstand as a vocalist," Ford says. "But my head was in the instrumental thing, and I thought, 'Let's just run with it. I am feeling it.' And indeed, that's why I did the instrumental record."

Robben Ford's Gear

Since 1983, Ford had used the same amp on all his albums—the second Overdrive Special built by Howard Dumble, with a 2x12 Dumble cab—until 2018. "It's been a revelation for me to get into the smaller amp thing when recording," he says.

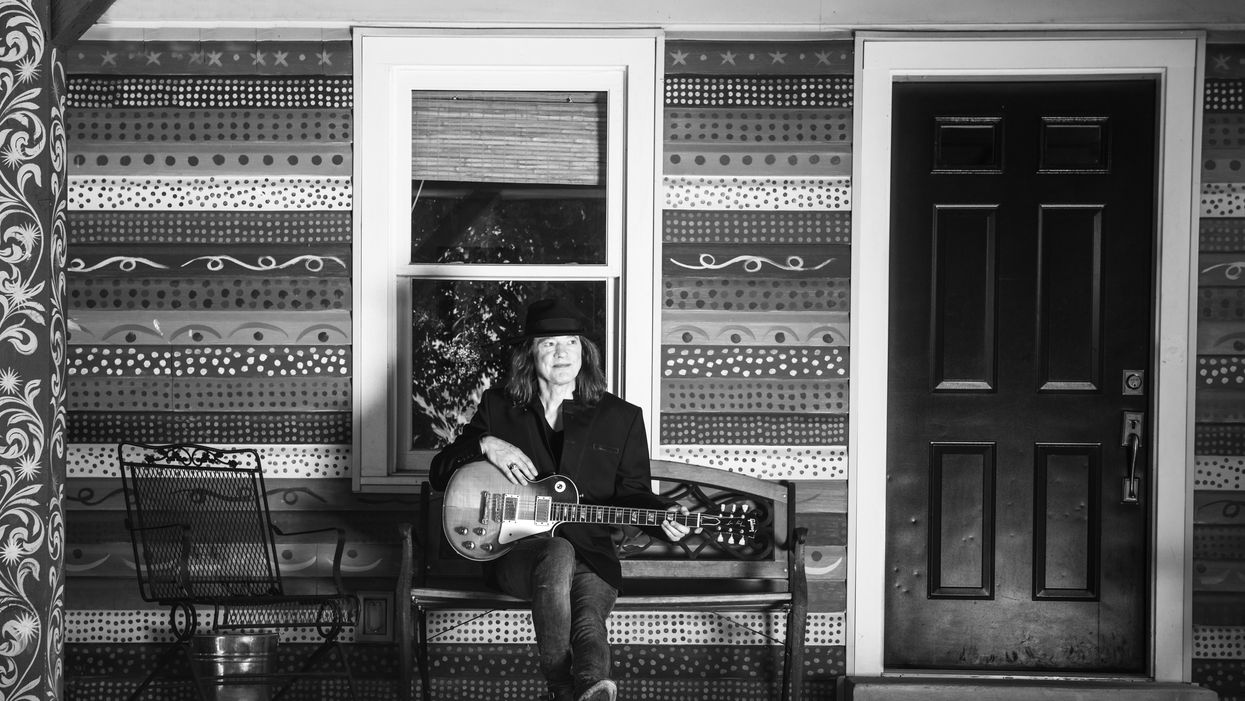

Photo by Joseph A. Rosen

Guitars

- 1960 Fender Telecaster

- 1952 Fender Telecaster

- 1966 Epiphone Riviera

- 1964 Gibson ES-355

- 1964 Gibson SG

- Assorted Paul Reed Smith guitars

Strings & Picks

- D'Addario (.010–.046)

- D'Addario heavy picks

Amps

- Dumble Overdrive Special (100 watt)

- Dumble 2x12 Cabinet

- Little Walter "59" (50 watt)

- Little Walter King Arthur (15 watt)

Effects

- Hermida Audio Zendrive

- Cornerstone Music Gear Gladio preamp

- Strymon TimeLine Delay

- Electro-Harmonix Micro POG

It's a setting that plays to Ford's strengths—the most prominent being his use of dynamics. He doesn't dime his amp and scream at you song after song. He tells a story, mimicking the natural inflections of speech. It's a skill he's mastered and, according to him, is the result of growing up immersed in the blues, followed by developing a passion for horn-centric jazz.

Rig Rundown - Robben Ford

Watch Robben Ford and Nashville luthier Joe Glaser go over his live setup.

Another way Ford changes things up is in the subtle use of his pick. He regularly plays by holding the pick backward and using the rounded end, but switches to the pointy end when aiming softer and lighter. He'll also vary the timbre by intuitively moving his picking hand between the neck end and the bridge, which is more percussive and punchy.

TIBIT: The new album was recorded at Purple House, an intimate studio outside of Nashville owned by Ford's co-producer, engineer, and second guitarist, Casey Wasner.

"I've always been trying to find it on the guitar as opposed to with an effect," he says about searching for the right tone. "That's another deliberate choice. Rather than going to a pedal, I'll try to get nuance using the pick and volume. It's just the way I learned how to play. The blues players and tenor players, man, those guys weren't using effects." But he's not an anti-pedal purist (despite the album's title), and pedals have factored into his tone for decades. "We have so many colors on the new album that I am trying to find them and recreate a little of what happened on the album through effects. This is a new phase for me. I'm using two different overdrives instead of just the one, because I need that other color. I am also working a lot with the Strymon TimeLine Delay. I've been using that for a while, but really just for short and long delays, nothing special."

Ford's main overdrive, for decades, is the Hermida Audio Zendrive. He's been through a number of units, but it's been a staple. He's also added a second overdrive to his pedalboard: the Gladio preamp from the Italian manufacturer Cornerstone Music Gear.

Robben Ford Show 6º Festival de Blues e Jazz

Here's Robben Ford defining great tone in a 2021 livestream show from Nashville, with his 1961 Gibson SG.

"It's basically an overdrive pedal," he says. "The fellow basically designed it trying to capture what he heard me doing with the Zendrive. He sent pedals to my friend Jeff McErlain. Jeff is a guitar player from Brooklyn. I produced his album, and he's been very helpful to me in terms of gear. He's turned me on to things that I was unaware of, and the Gladio was one of them."

Another essential element of Ford's tone has been his Dumble Overdrive Special, which he's been using since 1983. Since all Dumbles are built for specific players, Ford's was made by Howard Dumble with his particular tonal needs in mind. That amp—the second Overdrive Special built—still comes out occasionally when he plays live, but in the studio, since moving to Nashville, his needs have evolved.

Ford's latest album features several guests, but his core band is Casey Wasner on guitar, Michael Rhodes on bass, and drummer Shannon Forrest.

Photo by Mascha Thompson

Ford was recording 2018's Purple House at a studio in Leipers Fork, Tennessee, called—you guessed it—the Purple House, when he realized that the Dumble wasn't going to work. "The Purple House is a studio owned by my co-producer and engineer, Casey Wasner. It's a small house and the rooms are small—the rooms aren't live—and I tried using the Dumble and it was just too big. Everything was being recorded in one room. It was a small, dead room, and the drums, bass, and myself—with my amp and a cabinet—were in that one room. The bass was direct, and Casey was in the control room playing rhythm guitar, along with a second engineer. No matter how hard we tried, the Dumble just didn't fit. I always work in a much more spacious environment. I like larger rooms. When we did that record, it was an experiment. I learned a lot about recording—how to record and how to use the studio—and, in particular, I got comfortable with small amplifiers."

"I don't want to change the way I play. It took a long time to get here."

For Ford, getting comfortable with small amplifiers meant finding a way to adapt to the new situation without changing the way he plays. "That was the journey," he says. "How do we keep the vibe? I don't want to change the way I play. It took a long time to get here. I had to find a way. It was hard for me, and it was a struggle. It took about four months during the making of Purple House to feel like, 'Okay, now I get it.' There were times when we went into a really righteous overdub room where I could crank the amp up. It's a real process and, for me, not one that I ever paid that much attention to. Up until Purple House I had always worked in larger rooms, with the same amp and cabinet, and some great engineer. I've been doing this for 30 years. It was a big change but cool. I am really happy having had the experience and having learned these things."

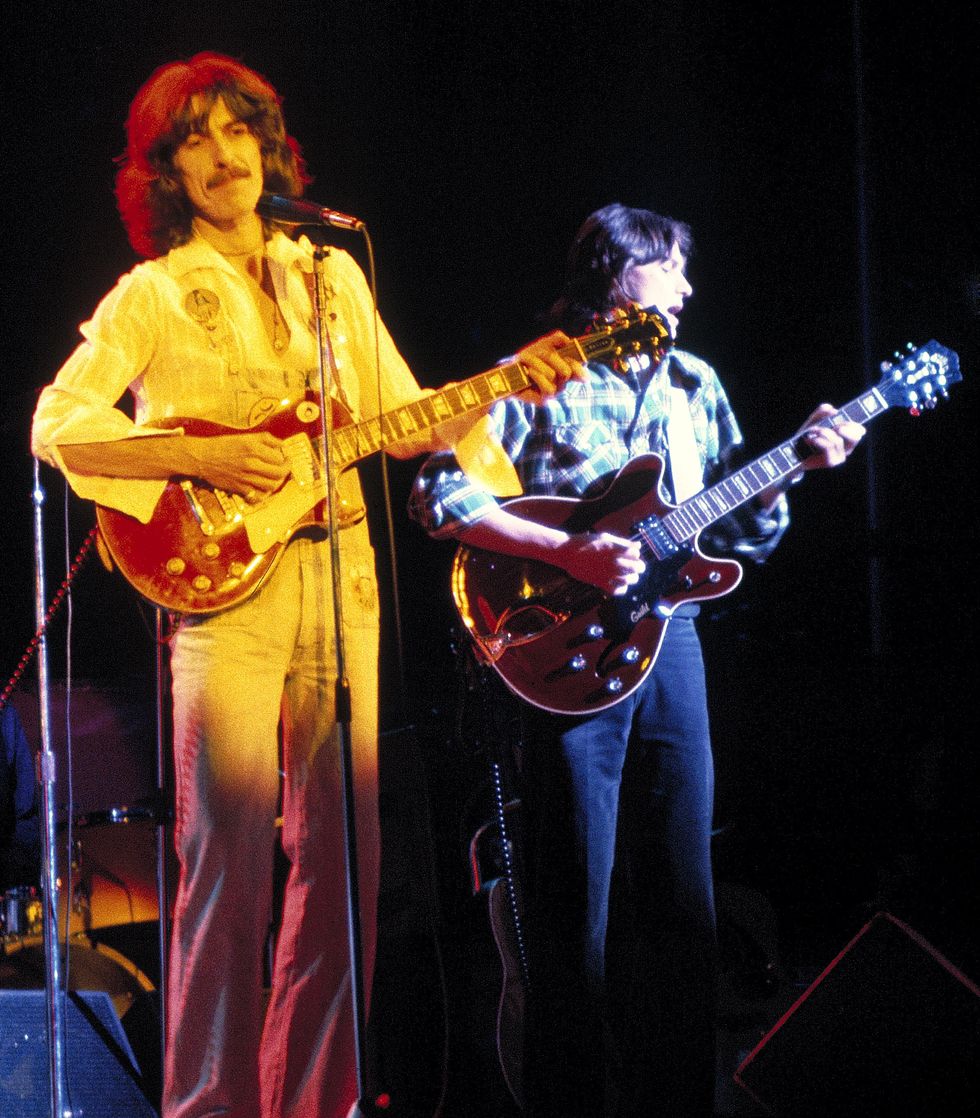

Back in 1974, George Harrison hired wunderkind 23-year-old guitarist Robben Ford for the George Harrison and Friends North American Tour.

Photo by Jim Summaria/Frank White Photo Agency

Ford took those lessons to heart, and he's continued in that vein on Pure. In the studio, his primary amp was the Little Walter "59," which is a 50-watt head, through a single 12" cabinet, which, despite what he's learned, is still taking some getting used to. "I've literally done every record I've ever made since Talk to Your Daughter (1988) with the same Dumble Overdrive Special and cabinet. [That's a 2x12, also built by Dumble.] It's been a revelation for me to get into the smaller amp thing when recording."

But despite his intensive efforts discovering the right tone—not to mention his years studying the instrument and developing his craft—ultimately, playing, for Ford, is intuitive.

"An analogy that I came up with for the way I play is that it's like finger painting," he says. "You put the color on the paper and then you brush it around. You're not making a square, necessarily, you're free flowing. It's more like clouds and wind. There is freedom in it, and it is never going to be the same way twice—it actually can't be the same way twice—because it's like brush strokes. I made a very conscious effort to take chances in the improvisations. It's always been very key to me, and, once again, it's a product of the people I listened to."

How to Play “That Out Shit”

(For more insight, watch Robben Ford explain—and play—diminished scale blues in this video.)

A big part of Robben Ford's playing is his use of the half/whole diminished scale, which is an eight-note scale that alternates half-steps and whole-steps over the course of an octave. It's a scale that's been in the jazz repertoire for decades and was a huge part of the Miles Davis sound throughout the 1980s. Ford was a member of Davis' band in 1986, although he began using that scale much earlier.

"A long time ago, I was 19, and my brother Patrick, a drummer, and I were playing with Charlie Musselwhite," Ford says. "We were on the bill with Larry Coryell at a club long gone in L.A. called the Ash Grove. At one point, I just asked him, 'How do you play all that out shit?' He said, 'I use the half-step whole-step scale.' And I was like, 'Okay.' I went back to my hotel room and went G, G#, A#, B, and I worked out the scale. That was in 1971."

"We were on the bill with Larry Coryell at a club long gone in L.A. called the Ash Grove. At one point, I just asked him, 'How do you play all that out shit?'"

One aspect of that scale's sound is the b9, which is a note Miles Davis often sat on. "Miles Davis would just play a b9 right on top of a seventh chord as his first note. I heard that sound, and from that time on I experimented with the half/whole diminished scale. Once I understood it through learning chords and realized it was a diminished scale and you could play it right off a #9 chord, that was the sound that I heard. I just got deep into it, and it has been a major quality in my playing."

Ford points out that all of the notes in a dominant 7th chord fit into the scale and says, "So there's my chord and I can play any of these notes. I can play a b9 against a G7—whether anybody likes it or not—and it's legit. I really work with that, and for me, that was the gift of Miles Davis."

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)