For forward-thinking modern artists, experimentation across genres and generations is nothing new. Whether it’s layering acoustic and digital sounds, adding pop flavor to blues-rock, or blending funk, R&B, reggae, and hip-hop, it can seem like there’s no other option than to stir all the multicolor, variegated influences of the past into something that’s refreshingly not quite any of the above. But when it comes to psych-folk, Latin-rock, alt-country group Calexico, melding musical worlds is not as much an experiment as it is an instinct.

The band’s guitarist, vocalist, and co-founder, Joey Burns, remembers when he fell in love with Latin music. It’s a story that begins with his first exposure to the bolero rhythm in the Beatles’ “And I Love Her” and weaves its way into a memory of one of his favorite films—a documentary from the ’90s called Latcho Drom (“Safe Journey” in Romani), which delves into a tale of global music history.

“We need more diversity; we need more language … however we can bring it in or just live by example and show everyone.”

“It’s about music from the Far East, Middle East, Eastern Europe, Southern Europe. It picks up Gypsy jazz, then goes to Spain for flamenco, and it stops,” he shares, gesturing the abrupt cutoff. “I’m like, why didn’t you keep going? Where’s Mother Africa, the Canary Islands, Cuba, South America, New Mexico, New Orleans, fado music in Portugal, Egypt, Ethiopia, North Africa, Mali, Senegal?”

Burns shares his abundant passion for wide-ranging global musics with fellow Calexico co-founder, drummer John Convertino. Their bandmates are an international network of musicians, and together they meld the sounds of cumbia, mariachi, alternative rock, and Americana. Their 10th full-length release, El Mirador, is a sonic travelogue that includes the mystical “Cumbia del Polvo” (“Cumbia of the Dust”), the whimsical “The El Burro Song,” which is a tale of a hungover lover sleeping on a bar’s dancefloor, and “Liberada,” which was inspired by a party in Cuba, but feels like it’s being told under the desert’s night sky.

Calexico - El Mirador (Full Album) 2022

TIDBIT: When the band set out to record El Mirador, they gave themselves a three-month tracking deadline, which included sourcing contributions from a host of international collaborators.

Livin’ in the Rhythm Section

When the band began recording El Mirador in June 2021, they set a three-month deadline until they would begin mixing. Burns, who now lives in Boise, Idaho, flew back to Tuscon, Arizona—his home of 27 years—to record with Convertino and multi-instrumentalist Sergio Mendoza in Mendoza’s backyard home studio. They recorded in two-week and one-week intervals, improvising and fleshing out the album in the studio.

“We started off with like 30 or so ideas. Then we woodshedded for the first two sessions—so a month of just woodshedding. And then from those ideas we kind of narrowed down the selection,” Burns explains. He says it’s his preference to do things that way, which makes him a nuisance to his bandmates—but clearly the method works. “We tend to just capture songs as they’re happening in real time,” he adds. “And to capture that feel, especially those first or second takes … it’s always hard to replicate. We’re just doing it live, in the moment, and I think that subconsciously highlights what I like about playing music.”

Burns and Convertino stayed with Mendoza at his home, which Burns describes as tiny. “We cooked a lot,” he says, adding that Convertino brought along a 1958 La Pavoni espresso machine, which kept the band caffeinated as they wrote and recorded. Mendoza lives near Tumamoc Hill—a nature preserve in Tucson that has a sacred connection to the local Tohono O’odham tribe—where Burns would go on hikes in the cool early mornings, listening to rough takes, mixes, and ideas to gauge his impressions.

“Turn off your brain, just listen to your heart—feel the tone or taste the cooking. Be experimental.”

As Burns puts it, El Mirador “mainly lives in the rhythm section.” To hear an example, the guitarist points to the title track. “It started on a bass line,” he says, playing it on his Manuel Rodriguez e Hijos nylon-string. Mendoza put cumbia-style woodblocks on top, giving it an “immediate lift.”

With the song’s foundation established, they sent the tracks to Guatemalan singer/songwriter and long-time friend Gaby Moreno, who added vocals. Next was Italian guitarist Alessandro Stefana, who added a Marc Ribot-style electric guitar solo, followed by trumpet players Jacob Valenzuela and Martin Wenk (Valenzuela currently lives in Tucson and Wenk lives in Leipzig, Germany). Lastly, they wanted some “really over-romantic violin playing,” so they sent it to DeVotchKa’s Tom Hagerman, in Denver, who added strings as well as some accordion.

“We’ve got what I call the Calexico orchestra,” Burns enthuses. “It’s Old World meets New World. It’s something that I’ve just been loving to assemble from time to time. It was like this swap-meet or thrift-store orchestra.”

Joey Burns’ Gear

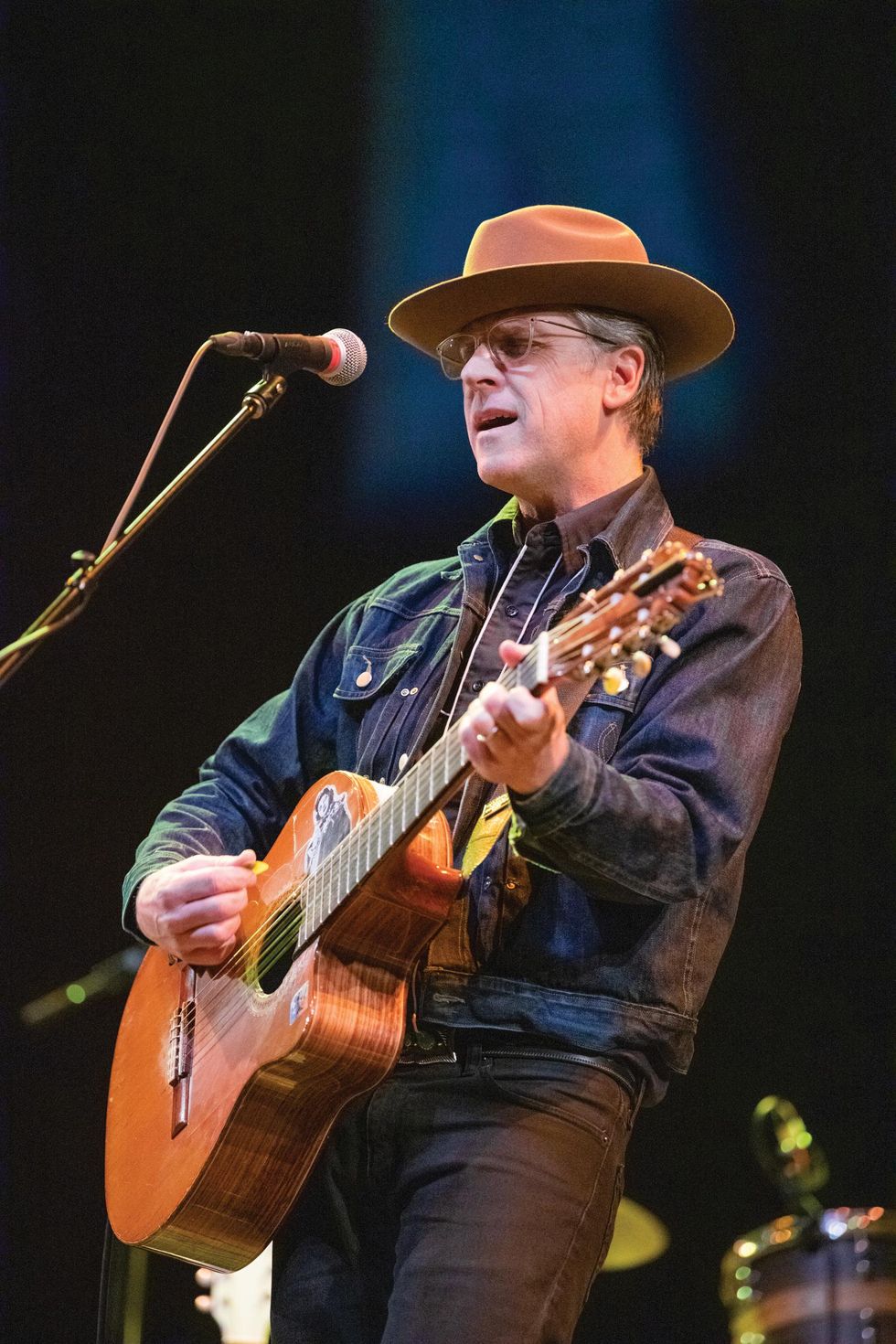

Burns belts it out with one of his two vintage Airline Res-O-Glas guitars, which proudly sports a Bigsby, three pickups, and a lot of knobs!

Photo by Matt Condon

Guitars

- 1962 Airline 3P Res-O-Glas (white with three stock pickups and a Bigsby)

- 2000s Manuel Rodriguez e Hijos nylon string acoustic guitar

- 1960s Fender Jazzmaster

- 1950s Harmony single-cutaway archtop with one pickup

- Guild steel-string acoustic guitar

- 1970s Univox hollowbody bass with flatwounds

- Fender American Deluxe Stratocaster with Suhr V60LP single-coils and Suhr SSV humbucker

- Chris Schultz-built T-Style with Vintage Vibe P-90s

Strings & Picks

- D’Addario for electric and acoustic

- Dunlop .73 mm

Amps

- Carr Rambler

- Magnatone Twilighter

- Fender Blues Junior

Effects

- Red Panda Particle

- Way Huge Pork Loin

- Smallsound/Bigsound BUZZZ

- Diaz Amplifiers Texas Tremodillo

- Boss DM-2W Analog Delay

- Boss DD-5 Digital Delay

- J. Rockett Audio Overdrive

Four-String Inspo

Burns’ two main guitars are his Manuel Rodriguez e Hijos and his 1962 Airline 3P Res-O-Glas electric. Burns owns two of the Valco-built fiberglass guitars and says he found the 1962 model in a shop in Memphis while Calexico was on tour with the Dirty Three in 1998. On his nylon-string, Burns proudly displays a printed-out graphic of Portuguese fado singer Amália Rodrigues. “She’s the patron saint of the minor blues,” he says, smiling. “I wanted to see her or talk to her or talk about her. And then there’s a stamp of Lydia Mendoza down there,” he gestures. “I’m a fan of female singers.”

He’s holding the acoustic guitar as he discusses the album and his influences, and frequently embellishes his stories with musical excerpts. Whether he’s playing “And I Love Her” or album tracks like “El Mirador,” “Turquoise,” or “Liberada,” his hands always go straight to the groove or bass line, a remnant of his past life as a bassist.

“I have two older brothers, John and Mike, and they said, ‘There’s enough guitarists in the world. Why don’t you just play bass? You’ll probably get to be in more bands or have more opportunities,’” he shares. He took their advice and studied electric bass, later joining the high school jazz band, where he gravitated more towards the Latin material they played, including samba and Afro-Cuban music. “I just loved anything where the bass was freed up,” he says, playing a syncopated bass line. “I love that push and pull. That, with minor chords and modes and melodies … I just love it. I’ve always been drawn to songs in minor modes. I’ve always loved Latin rhythms.”

Look closely and you’ll see fado singer Amália Rodrigues and Mexican-American vocalist/guitarist Lydia Mendoza bedazzling Burns’ Manuel Rodriguez e Hijos nylon string.

Photo by Debi Del Grande

One of his biggest influences is David Hidalgo of Los Lobos, who, he says “paved the way immensely in regards to what you can do with guitar, embracing so many different rhythms and genres, tone, technique, soulfulness.” Then there’s Andy Summers of the Police—who he once got to sign his guitar when he saw him at the airport—and Peter Buck of R.E.M., who he loves for his use of drone, adding, “That really connects with a lot of music from around the world.” He then begins to play the Smiths’ “Well I Wonder” as he mentions Johnny Marr, who he describes as both emotional and technical. And lastly, there’s D. Boon of the Minutemen, whose “fierce Tele jabs” he admires and likens to those of Joe Strummer. Burns sees a connection between all these artists, which he calls their “guitar duality.” “All those bands, whether it was two different guitarists or one, recorded parts that were complementary—that kind of push and pull to help with the vibe of a track or a song.”

Music Is the Connecting Force of the Universe

It’s no surprise that Burns sees music as one of the best ways to connect with other cultures. “And food,” he adds. “It’s like, turn off your brain, just listen to your heart—feel the tone or taste the cooking. Be experimental.” Naturally, he’s speaking from personal experience. “My instruments help me get to that meditative place, that poetic space. Getting immersed in tone is a good thing. Because at the end of the day, we are all just frequencies and sound waves and particles, and if we can help restore the connections between all things … I think that’s a good thing to do.”

And it’s one of the things he set out to do on El Mirador. “On this record,” he says, “it’s all about laying down the groove, laying down the foundation, and seeing what we can do to get people to move. Because if they can’t overcome fear with words, then maybe their body can help them overcome whatever difficulties or obstacles are in the way.”

“At the end of the day, we are all just frequencies and sound waves and particles.”

Musing about music’s powerful role in connecting groups of people, Burns shares an anecdote from the ’90s, when he and Convertino were members of the group Giant Sand. They found themselves playing at a festival with Romani band Taraf de Haïdouks (which translates to “Band of Brigands”), and, at one point, the festival organizers had the two bands go onstage together to jam.

“At the end I swapped sunglasses—my cheap Arizona truck-stop sunglasses for the cheap Romanian truck-stop sunglasses—with one of the accordion players. And we were best friends after that,” he laughs. “That’s one of those moments where you’re like, ‘How come politicians can’t do this? Why can’t there be peace talks with music?’

Calexico And Iron & Wine: NPR Music Tiny Desk Concert

Watch Burns and Co. deliver a trio of strummy acoustic tunes alongside longtime friend and collaborator Iron & Wine.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)