Carlos Santana plays like a superhighway. His notes—always exquisite and succulent—are founded on terra firma yet travel to many places. The 74-year-old 6-string guru often uses the word multidimensional to describe his technicolor sonic thumbprint. And, through more than a half-century of recordings and concerts, that multidimensionality speaks as articulately as the beautiful unison-string bends in his band’s classic “Samba Pa Ti,” projecting his devotion to melody, intention, the echoes of his influences, imagination, inspiration, awareness, fidelity to his art, and a desire to communicate.

Of all those dimensions within Santana’s playing, his desire to communicate and his awareness that his music can telegraph a subtly different message to each listener may be the most important. It’s key to understanding the search he embarks on every time he takes a solo or writes a song. Or makes a new album, like the recently unveiled Santana band recording Blessings and Miracles, which seems to draw on every period of his career—or at least all the aspects of his search for, as he called it in the title of his 2014 autobiography, the Universal Tone.

Santana, Rob Thomas, American Authors - Move (Official Music Video)

“I think of melodies that are universally accepted—by Greeks, Apaches, Puerto Ricans, Aboriginals … everybody,” Santana explains. “Because everyone understands the sacred language of melody, nothing speaks more clearly, and you can hear the way melodies transcend any cultural differences. For example, play the first four notes of ‘Nature Boy,’ by Nat King Cole. [He sings the intro to the song’s melody, and then sings the same notes with different phrasing.] See, it’s also ‘Danny Boy’—the same four notes.

“We’re in the business of getting people’s attention,” he continues. “Understanding the universal nature of melody is important. I have never created and will never create an album that’s background music. I don’t do background music. When you go to hear Santana, like the people I love … Miles [Davis], Stevie Ray Vaughan, the music has to take center stage and captivate your attention. It tries to offer you something that’s really good in you and for you, that you aren’t aware of.”

Everyone understands the sacred language of melody.

One of those somethings is the long, held note—an emotional trigger that’s among his historic signatures. “Feedback is good for you,” Santana says. “With the correct tone between the pickups and speakers, it’s a living light, it’s constantly breathing. But feedback coming from a pedal is bad feedback. It’s like a cadaver. There’s no life in there. So I don’t use pedals for sustain. I walk around and mark the floor where the sound becomes a laser beam between me and my guitar, so it’s constantly breathing. That’s why we like Star Wars. You get to hear Darth Vader breathe.” Parenthetically, that notion also correlates with the healing feeling that comes with yoga’s soothing ujjayi, or ocean, breath.

With the title Blessing and Miracles tagged to his namesake outfit’s 26th album, it’s no surprise that Santana self-produced the recording with high goals. “There’s no difference between radio today and in the ’50s,” he relates. “It was corny, boring, and then along came the Doors with an eight-minute version of ‘Light My Fire,’ and the Chambers Brothers, with ‘Time.’ I grew up in the ’60s with the ground-zero cultural revolution, so it’s natural for me to play my guitar sometimes melodically and contained, and sometimes like a hurricane. If I play something like ‘Maria Maria’ [from Santana’s 1999 mega-hit Supernatural] it feels commercial because it has a regular melody, but if you put some Sonny Sharrock and John McLaughlin influence in there, that’s radical! And that’s exactly what the world needs today—to get far out!”

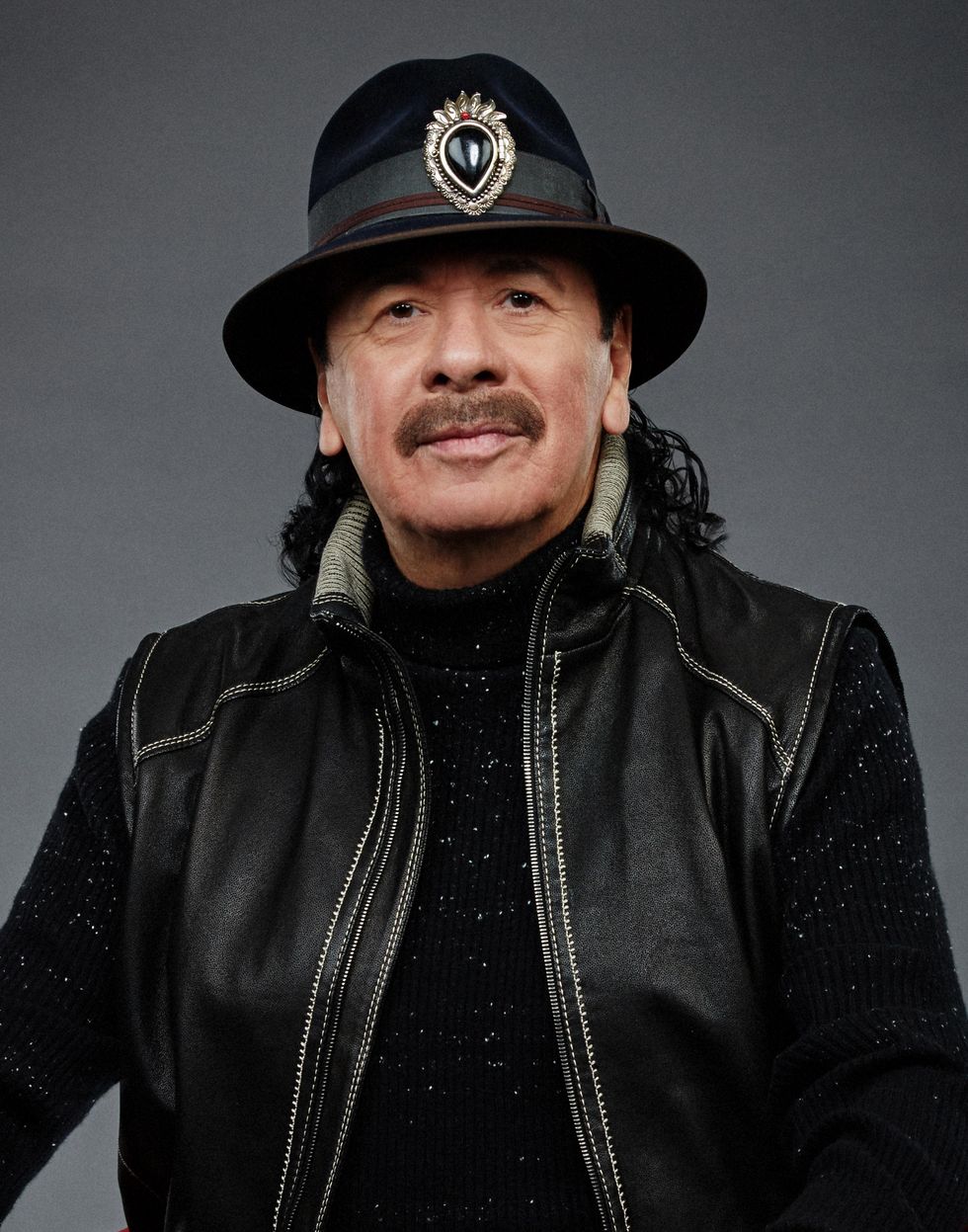

At 74, the éminence grise of Latin-rock guitar is still taking chances and believes that music can change the world.

Photo by Maryanne Bilham

To get far out music to the people, Santana figured he also had to go deep inside the industry. So, over the several-year course of making the 15-song album, he recruited Chris Stapleton, Steve Winwood, Living Colour’s Corey Glover, Metallica’s Kirk Hammett, Chick and Gayle Corea, and his old Supernatural teammate Rob Thomas. Santana and Thomas’ song on that triple-platinum album, “Smooth,” spent 12 weeks on top of the Billboard charts.

“I’m at a point where intention, motive, and purpose are very, very clear,” Santana says. “I wanted names that would help get me back on radio. We didn’t do any planning like that for Africa Speaks. [The exploratory Afro-Latin album the Santana band made in 2019 with Spanish guest vocalist Buika.] But now is the time.

Carlos Santana’s Gear

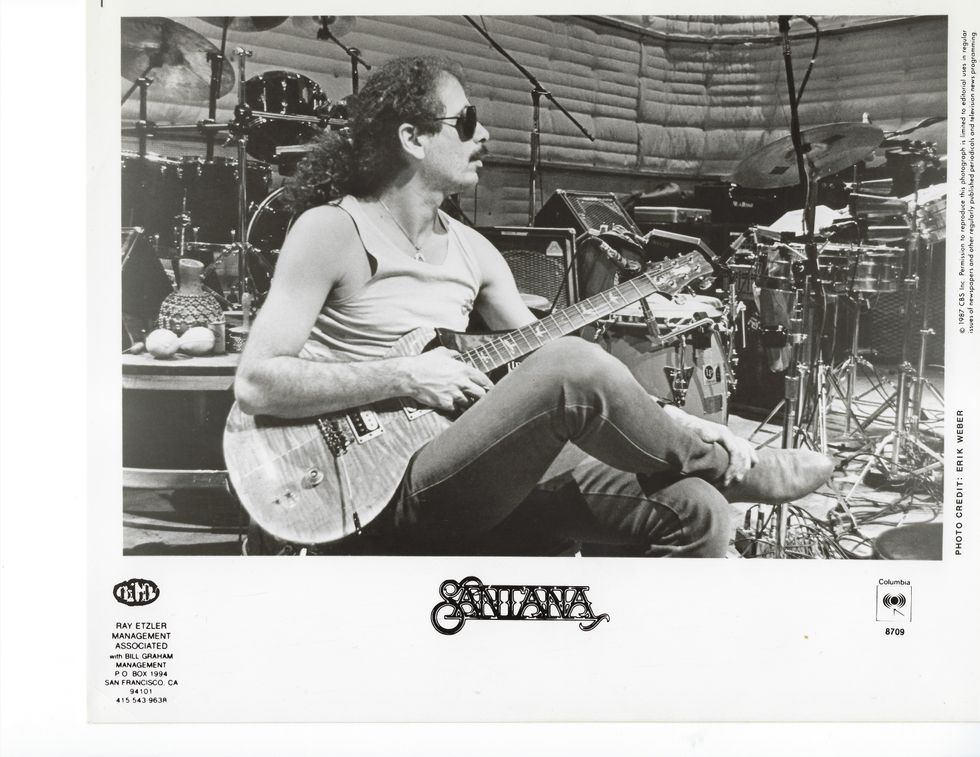

Carlos Santana is using three PRS custom guitars for his Las Vegas residency: two gold-leaf-finished Single Cuts—one with a vibrato bridge—and a red flame-top Single Cut. In this photo, he's playing an earlier Double Cut PRS signature model, but he now favors his Single Cuts.

Photo by Roberto Finizio

Guitars

- PRS Custom-Built Single Cut non-trem with gold leaf finish (main guitar)

- PRS Custom-Built Single Cut tremolo with gold leaf finish

- PRS Custom-Built Single Cut non-trem with red flametop

- Toru Nittono Jazz Electric Nylon model

Strings & Picks

- Paul Reed Smith Signature Series (.0095–.044)

- Dunlop Carlos Santana Signature medium soft

- V-Picks custom 3 mm in red

Amps

- Dumble Overdrive Reverb 100-watt head

- Allston Neuro 100-watt head

- Tyrant Dictator 4x12 with Weber Gray Wolfs

Effects

- Real McCoy Custom RMC10 wah

“It’s imperative to uphold enthusiasm no matter what the world is going through, because we can push the buttons and click the switches to change the narrative. There’s too much fear and separation on the planet—too much crawling instead of flying like a hummingbird. So people find a lot of ammunition to justify why they’re unhappy. We with the Santana band say get away from here with that stuff. We override it and we change it, because we want joy—which we can provide through our music—to transmogrify fear. It’s that simple. I have confidence that, at 74, I can take this music to the four corners of the world and touch many people’s hearts.”

So Blessings and Miracles pendulums between the wild and the calculated, and, not surprisingly, Carlos Santana brilliantly breathes in both realms, as he has since earning his bones playing blues in the strip clubs of Tijuana, and then as a musical staple of San Francisco’s—as Otis Redding put it—“love crowd.” Even when the songs purr, like “Breathing Underwater,” a graceful textural-pop ballad his daughter, Stella, brought to the album, there is a radical quality to his playing. It’s in those long held notes that trail into ascendant feedback, in the exquisite slow bends that move like a human voice, and in the squalls of sound inspired by his touchstones Sharrock and Coltrane.

I have never created and will never create an album that’s background music. I don’t do background music.

Blessings and Miracles opens with “Ghost of Future Pull/New Light,” an overture crafted from bestial feedback, percussion, and melody. Then it plunges into the bold, Latin-rock instrumental “Santana Celebration.” That pairing is a flashback to the band’s early ’70s days, and, in particular, recalls the cosmic sizzle of the opening of 1974’s Lotus, arguably the most exciting, inspired live guitar recording of the classic-rock era. “Rumbalero” breaks the pattern. It’s Latin electro-fusion, with Santana’s son Salvador on vocals and composer/horn player/vocalist Asdru Sierra. There, the guitar constantly tosses off explosive mini-melodies as if they were kernels of popping corn.

Elsewhere there’s “Joy,” a reggae song featuring Stapleton, who wrote its uplifting lyrics at Santana’s urging. And “Move,” which sounds like exactly what it is—Santana and Thomas’ update of “Smooth.” With Winwood, Santana takes on Procol Harum’s “A Whiter Shade of Pale.” The social-justice-fueled rocker “Peace Power” features Glover, and the gritty metal critique “America for Sale” has Hammett and Death Angel’s Mark Osegueda as its guests. Both Coreas play on the merry, peaceful “Angel Choir/All Together.” By the time that’s all unreeled, it sounds as if Santana aimed not only at radio, but at nearly every format. And he’s crafted another “Europa”-level melodic-guitar showpiece with “Song for Cindy,” written for his wife, Santana band drummer Cindy Blackman Santana.

What does Carlos Santana practice the most? “Learning to dive into totality, absoluteness, and infinity in one note.” Here he squeezes a Blue Africa Santana SE Doublecut with custom graphics, by Paul Reed Smith. It’s one of seven made concurrent with the Africa Speaks album.

Photo by Jay Blakesberg

Despite all the guest vocalists, the real lead singer, of course, is Carlos Santana, whose custom Paul Reed Smiths ooze emotion. (PRS recently released another limited-edition Santana signature model, the Abraxas 50, to celebrate the anniversary of the Abraxas album’s 1970 release.) After all his decades of gorgeous tone, that’s to be expected. As is the presence of the wah-wah pedal, which, under his foot, can quack like a peyote-eating duck, roar like a tyrannosaurus, attenuate his singing strings, and make notes kaleidoscopic. Santana is among the greatest proponents of the effect, and has been since 1970’s “Hope You’re Feeling Better.” But at that point, the only pedal that would become part of his sonic mug shot was more novelty than staple for the guitar legend.

“I first heard the wah-wah within Cream’s Disraeli Gears, and then Hendrix’s ‘Voodoo Child,’ and Mel Brown used it incredibly well in ‘Eighteen Pounds of Unclean Chitlins,’ which is super funky,” Santana says.

“I had only used it on some songs in the studio, when one day in 1970, I was in an elevator in New York City with Miles Davis and Keith Jarrett, and Michael Shrieve and Michael Carabello from my band, and Miles goes: ‘Hey, you got a wah-wah?’ I said ‘no.’ And he said, ‘I’m playing my trumpet through a wah-wah. You gotta get an effin’ wah-wah, Carlos.’ I said ‘okay.’ So I got an effin’ wah-wah, and I’m grateful Miles took me out of that other zone where I had no wah-wah regularly, so I could learn to create textures with it.”

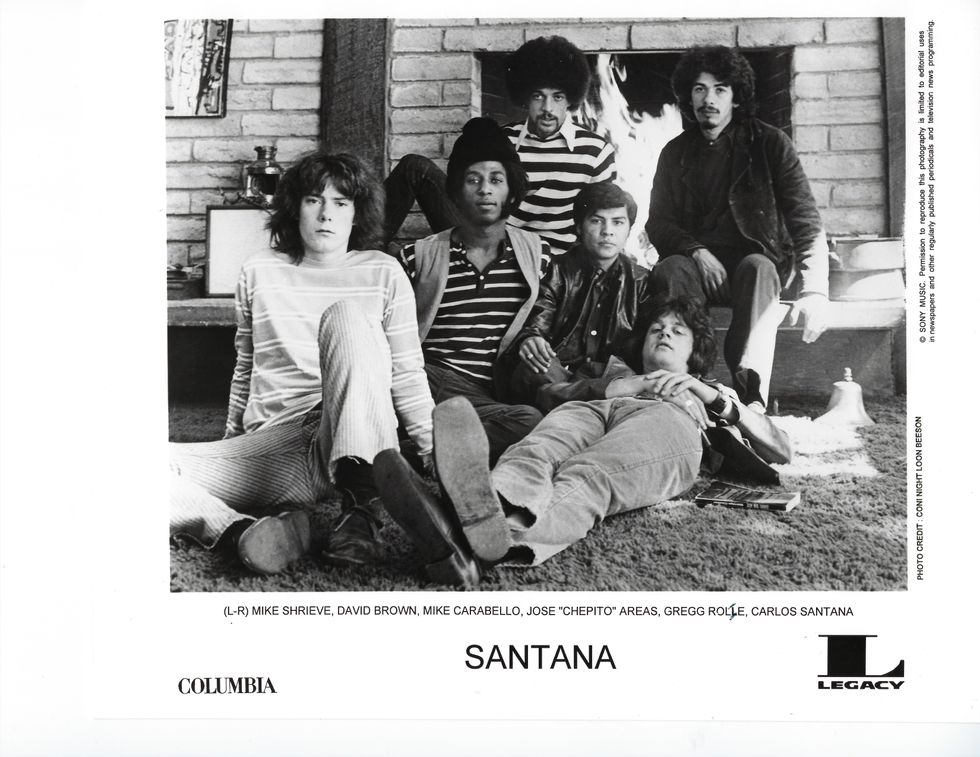

The original Santana band line-up (left to right): Michael Shrieve, David Brown, Michael Carabello, Jose “Chepito” Areas, Gregg Rolie, and Carlos Santana.

Tone fiends may have noticed a subtle shift in Santana’s guitar sound on recent albums—darker, beefier, with a bit more grit. For Blessings and Miracles, his return to Dumble amps plays a role in that, but he also notes that—after many years of trying to get his guitar sound on tape accurately—“I’ve been able to get the engineers to open up the depth of field. I always had a tone, but it was a challenge to teach people how to capture it. It’s like photography: You have to open up the aperture to let as much light come in as you need.

“I need four or five microphones on my amp in a room: one in front, one behind, one above, one right on the speaker, and one as far away as possible,” he explains. “I go to each microphone and subtly adjust the position until I get it right. I learned how to record guitars from Jim Gaines and some other engineers and producers. If someone doesn’t know how to record electric guitar, it can sound shrill, metallic … it hurts your teeth. My sound needs to sound like Pavarotti and Placido Domingo—chest tones, head tones, four or five different tones in one note.”

Rig Rundown - Carlos Santana

In January, February, and May, it’ll be possible to hear those tones live in Las Vegas, of all places, where the Santana band started a residency at the House of Blues last year. (His December dates where cancelled for an unanticipated heart procedure.) “Thirty years ago, I would never consider playing a place like Las Vegas or Broadway,” says Santana, who has always been highly vocal about his music-over-showbiz aesthetic. “I was ignorant and afraid if I did something like this I would become predictable, mundane, and boring. I didn’t realize that I could play anywhere repeatedly—without having to move the amps and realign the sound for the stage and the room—and use it as a laboratory, which is what I’ve been doing. I know people come from Australia or Paris to hear certain songs, and I’m going to play something they relate to, like ‘Black Magic Woman’ or ‘Maria Maria,’ but in the middle of the set I’m going into the unknown. I can change the tempo, the melody … play anything.

“I was doing an interview with a guitar magazine and they asked, ‘What do you practice the most?’ I said, ‘Learning to dive into totality, absoluteness, and infinity in one note.’ That way everything can be fresh and new every time you play it. How do you learn to do that? Well, you have to learn to meditate, even while you’re playing. When I hear Metallica, I can feel their collective energy. Collective energy is like supreme meditation. That’s also what I love about Sonny Sharrock. [Santana has a Sharrock tribute album in the works.] At this point in my life, when people say, ‘What’s on your mind?’ I say, ‘Nothing, thank god.’ Because that’s when you play your best.”

My sound needs to sound like Pavarotti and Placido Domingo—chest tones, head tones, four or five different tones in one note.

Actually, there are a few things on Santana’s mind—or at least within his intentions. He says that over the next six months he’d like to learn how to surf, and how to cook bouillabaisse. He’s also enjoying the work of his Milagro Foundation, a non-profit that strives to help children through health care, education, and the arts. Profits from the Carlos Santana Coffee Company, which launched in 2020, goes to Milagro’s work, which is currently focused on clean water for Native Americans living on reservations.

Santana’s own life is perhaps one of the greatest success stories in rock: A poor kid from Mexico falls in love with music and immigrates to the U.S. to chase his muse, and finds more struggle—a bout with tuberculosis, racial discrimination, a language barrier, continued poverty. And then even more struggle, trying to find his place in the rock world, seeking balance in the spiritual dimension with guru Sri Chinmoy, and ultimately becoming a superstar and an éminence grise of guitar. More important, he seems like a joyful man living a life of decency and depth. Which prompts the question: What makes him truly happy?

Carlos Santana circa 1987—the year the band released Freedom and Santana issued his solo album Blues for Salvador, dedicated to his son. The latter yielded Santana’s first Grammy, for Best Rock Instrumental Performance.

“Knowing that I am worthy of my own life of grace,” he says, “and knowing that sometimes when the phone rings, it’s going to be Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, or, in the past, Miles Davis … musicians at that level, calling to say hello and see how I’m doing. That makes me happy being Carlos. He’s quite a guy.

“One of the most important things John Coltrane said is, ‘One positive thought creates millions of positive vibrations.’ You don’t have to be a musician to understand that. It’s inviting you to be miraculous. I talk about this all the time with Eric Clapton and Derek Trucks. Just the way you walk onstage before you grab the guitar can bring hope and courage. You can make a difference. I say to people, ‘You can make the impossible tangible.’ And they say, ‘You’ve been smoking too much pot.’ And I say, ‘Maybe you need to smoke a joint?’”

He continues: “How do you get into a solo that’s in the same place Charlie Parker, Beethoven, or Stravinsky would go to? We can get to that same place. It’s called The Sanctum-of-My-Intelligence Hang-Out. People say to me, ‘That’s far-out, dude! How do I get there?’ Practice removing your mind from the room and allow your light-spirit and soul to create music outside of gravity and time. You have to get out of the cage and dive into the unknown and the unpredictable.”

Santana - Soul Sacrifice Live (Original Líne Up) | Santana IV

See Carlos Santana—gold-leaf-finished PRS in hand—evoke the spirits of tone on the classic “Soul Sacrifice” at the Las Vegas House of Blues with members of the Santana band’s classic line up, including vocalist/organist Greg Rolie and drummer Michael Shrieve.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)