When the great Ronnie Spector of the Ronettes passed away earlier this year, I thought a lot about Johnny Marr. Marr was moved deeply by the girl groups of the ’60s—their positivity, energy, and the convergence of ecstasy and melancholy in the music. He was even fired up by the audaciousness of their style: The impressive beehive hairdo worn by Spector’s bandmate Estelle Bennett famously inspired the jet-black pile Marr wore at the height of Smiths fame.

But the most lasting influence of the girl groups on Marr is probably the musical playground that Ronnie once made her own: the wall of sound. In the decades since Phil Spector concocted the wall of sound from an orchestra of guitars, strings, drums, pianos, chimes, castanets, and whatever else was gathering dust in the closets of Gold Star Studios, scores of musicians—from Brian Wilson to the Beatles to Bruce Springsteen—have chased its elusive, ineffable magic.

Johnny Marr - Spirit Power and Soul (Live)

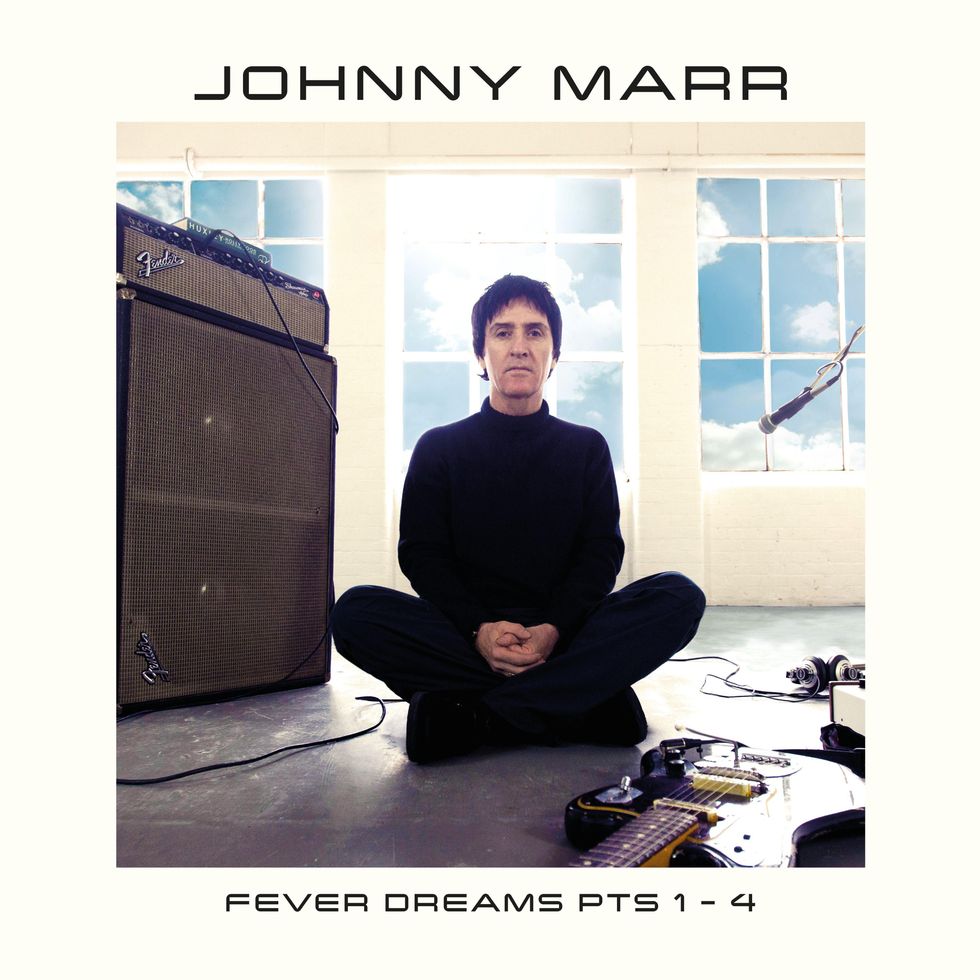

Johnny Marr’s versions of the wall of sound, however, are highly original and distinctive. They are marked by deep resourcefulness and a gift for achieving wall-of-sound grandeur and scale through the humble medium of multitracked guitar. And from the Smiths’ first LPs to his latest release, Fever Dreams Pts 1-4, Marr achieved this wizardry by mining a seemingly endless vein of riffs and through his penchant for guitar arrangement—talents cultivated through intuition, passionate listening, and a boundless, post-modern knack for tastefully blending influences.

As formidable as Marr’s arranging abilities, melodic instincts, and sense of musical recall are, they all find realization in hands driven by Swiss-watch timing, economy, and percussive potency. And though he’ll be the first to tell you he’s not a musical technician, he is, in many ways, as complete a musician as you could ever know.

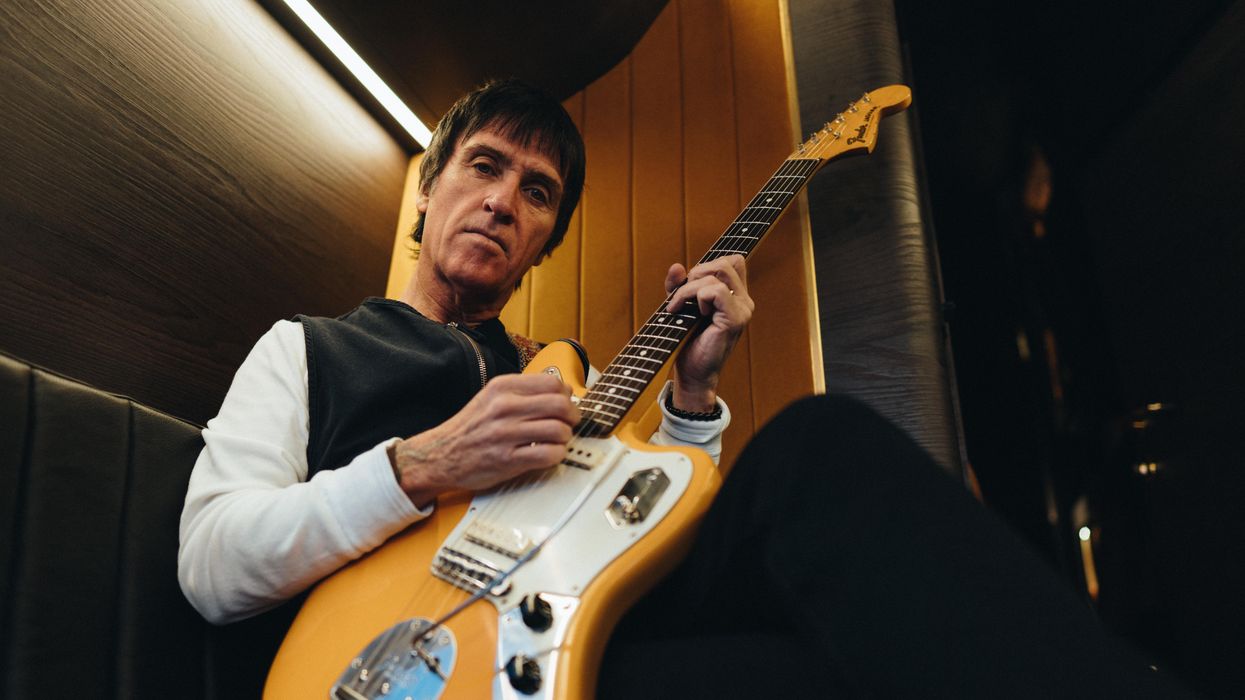

Johnny Marr with his closest comrade, the Fender Jaguar, at L.A.’s Teragram Ballroom.

Photo by Debi Del Grande

I was really struck by the bigness of Fever Dreams Pts 1-4. I pictured you making this record, amid lockdown, making music for the clubs we hoped to return to again. Even the picture of you on the cover—you next to the Fender Showman—seemed like a totemic suggestion of longing for big sounds.

I think that was subconscious. I say subconscious because I started writing it before Covid and had this idea that I wanted to do a double LP, and because it was going to be a double, I thought it could be expansive. I just had this idea that (the double LP format) would give me a lot of space. But, of course, with the way things turned out, I ended up—and I must confess, illegally—going alone into my studio space, which is the top floor of an old factory, staring out at my Mini, which was the only car in this vast parking lot, and working like that for weeks.

So, I ended up very aware of all this idea of space, which is even why the sky is so blue on the cover. I took all the equipment in the space out for that shoot to signify the way I was feeling about all that. There were also these nocturnal themes that emerged. I think a lot of people were lying awake wondering if they still had a job and worrying about their businesses. So, a lot of the songs reference those feelings—like “Lightning People:” “I can’t sleep/static sheets/cries that put me on my knees”—that idea of a storm coming.

I made the assumption that the part of my audience that listens most closely and that I’ve built up over the last 40 years or whatever, that they are living similar lives to what I was talking about. So, I didn’t have a concept, but I did have a sort of nagging agenda—that the album would be expansive and that I would tackle feelings about the psychology and predicaments of being a modern person.

“You know that concept of work/life balance? I don’t really have that concept. I hear good things about it and maybe I should try it out.”

The rhythmic drive and dance feel of many of the tunes also struck me as nocturnal. Was that a conscious thing?

Well, it’s funny how some things turn out. I started writing the album and just a few weeks into it, got the call to work on the Bond film [No Time to Die]. There’s a lot of downtime in that kind of situation, so I started working on the song “Receiver.” And as you said, it sounded to me like the atmosphere of being in a nightclub—like those I used to go to in [London neighborhood] Euston at the end of the ’80s—finding myself, you know, still there at 5:40 in the morning. So that song is about transmitting and receiving erotic signals.

That’s the beauty of songwriting. Sometimes you mix and match images or sometimes a concept comes first. The same thing happened with “Lightning People.” I had that title, which to me sounded like a Staple Singers song or something, so it ended up with a sort of choir/gospel feel. Musically, you can still tell that it’s coming from an indie rocker from Manchester, but the whole idea started from just that title. Lots of stuff still comes via the way people probably expect I write songs, too, which is to just sit down with a guitar. The last song, “Human,” is like that.

All the way back to the Smiths, you’ve always evoked feelings vividly through purely instrumental means—particularly those feelings that that cross sadness and positivity. But you really went after it lyrically here.

Well, in working with lyricists and paying attention to the ones I haven’t worked with, I’ve noticed that as a lyricist you have to be very self-aware and ask yourself, “Well, what am I really saying?” And in the case of this album, I was asking myself how I was going to top an album that was really well-liked among my fans. I know what that feeling is like. I don’t like to call that “pressure,” but that’s what it is.

Johnny Marr’s Gear

Marr never tires of the guitar. “If for some reason I was going to move to Bali and retire,” he says, “it would be to play for eight or nine hours a day and really expand my vocabulary.”

Photo by Debi Del Grande

Guitars

- Signature Fender Jaguar

- 1973 Les Paul Custom

- Gibson EDS-1275 doubleneck

- Yamaha SG-1000

- Yamaha SG-700

- 1963 Fender Jazzmaster

- Martin D12-28

- Auden acoustics, 6-string and 12-string

- 1984 or ’85 Gibson Les Paul with Bigsby

- Gretsch 6120

Strings & Picks

- Ernie Ball Power Slinky strings (.011–.048)

- D’Addario acoustic strings (.012–.053)

- Ernie Ball Medium picks

Amps

- 1969 Marshall plexi

- HH Electronics transistor combo

- Roland JC-120

- 1965 Deluxe Reverb

- Fender Twin Reverb (black panel)

- Kemper Profiler

- Fender Bassman

Effects

- MXR Flanger

- Carl Martin AC-Tone

- Carl Martin Plexitone

- Carl Martin HeadRoom Reverb

- Carl Martin Delayla

- Carl Martin Chorus XII

- Boss RT-20 Rotary Ensemble

You’ve experienced that pressure before: Trying to top Meat Is Murder with The Queen Is Dead.

Before The Queen Is Dead, I remember a moment where I was walking through my kitchen and stopped in my tracks, just literally frozen, realizing what it was going to take to do that. And when I was doing Dusk with The The, I remember the feeling when Matt Johnson and I realized the record was going to completely dominate our lives for two years. And with this record, in particular, I probably was feeling the pressure of following Call the Comet, because I was literally writing 48 hours after the last show to support that record.

Was the decision to background guitars in some cases on this album also a response to that record?

Deciding where guitars should sit in more electronic music is a balancing act. It’s very easy to get it wrong. One way I’ve done it wrong in the past is by not putting enough guitar on. Like with Electronic’s second album, I was trying to make my guitar sound like a synth. But at the time, that was part of my agenda—taking guitars out, seeing what filters did, things like that.

But honestly, I don’t really like a lot of music that blends electronic music and guitars. So, when I do it, it has to be appropriate and really capture a feeling. I think I know enough to do that well now. A song like “Ariel”—a lot of people hear that as very ’80s, and the riff is built on a sequencer. But I made the riff really loud and it’s a very ’80s, Roland Jazz Chorus riff. So, there I really doubled down on the contrast between the electronic and guitar elements. On “Spirit Power and Soul,” if you take the guitar out, it’s a totally different kind of track, and the guitar is backgrounded. So, I think I know how to find the right blend better these days.

Given that newfound freedom, did you write a lot more of these tracks from rhythmic underpinnings? It seems like working alone may have forced your hand in that respect.

Yeah. I don’t mean to take any credit away from my amazing band, which has been with me for more than 10 years now. But the entire record was demo’d and programmed with me playing everything on it. Then the band came in to make it sound more like “us” as a band. But things like “Spirit Power and Soul,” I was hearing that sequencer pattern in my head long before I wrote the song, and I knew I wanted very much for it to sound like Giorgio Moroder, Kraftwerk, or Cabaret Voltaire but with guitars on it.

For Fever Dreams Pts 1-4, Johnny Marr worked alone in his studio, on the top floor of an old factory.

When I was in my teens, I had a tape player that I could overdub on—this was before I had a Portastudio—and I’d get into obsessively layering. This album is really the grown-up version of that. It’s that same guy, but he’s now been in The The, Modest Mouse, and all that stuff. And again, because I knew it was going to be a double album, I allowed myself to do whatever the hell I wanted. So, something like “Lightning People” and that gospel vibe—I never would’ve done that on The Messenger or Playland because on those records I had these very specific and deliberate parameters I was trying to work within. Which can be a very good thing.

When you’re a writer, and particularly when you’re very young, things often become very much about what you’re not. But in this day and age, when you have a universe of plug-ins, instruments, and directions at your fingertips—not only can you get option fatigue, but your music can become a stylistic hodgepodge. So usually, with the band I impose some restrictions that limit that. On this LP, though, I just stripped them away.

What did that feel like to embrace that freedom?

Honestly, I didn’t even know I was doing it until much later. Because of the lockdown I was usually alone in the studio, so I thought, “Well, let’s see what all these virtual keyboards and synths and machines that I’ve been buying for the past five years do.” First, I had to spend a week getting really frustrated doing all the updates to the point where I don’t even really want to make music. But then I’d wake up after three hours of sleep with a song in my head and be ready to go.

You’re a writer that famously goes on hot streaks and creative runs. Do you still experience that zombie-like sense of creative possession? And how readily are you able to tap into it? What tools do you use when you can’t tap into it?

This thing you’re talking about—finding inspiration and hopefully, some otherworldly place—finding that place is something that has driven me since I was a kid. But you know that concept of work/life balance? I don’t really have that concept. I hear good things about it and maybe I should try it out.

But without mythologizing things too much, when I make records, I tend to lock myself out of the house, or forget where I’ve left the car. I develop very odd sleeping patterns if I sleep at all. I decided many years ago that drugs, particularly cocaine, don’t do any good, and alcohol isn’t really good for my creative process—maybe when you’re younger.

So, it gets back to that quote of Picasso’s: “Inspiration exists, but it has to find you working.” In my own process, that means I’ll work on a song—and for it to snag me, the initial feeling has to be something like, “This is the greatest thing that no one has ever heard.” That’s entirely subjective, but that energy will keep you locked in for a couple hours and if you’re really lucky you’ll get on a real roll and you’ll end up with something inspired. Sometimes you do something for a couple hours and you realize, “Ah, this isn’t so great,” and you have to drop it. Emotionally, that can take you down. Especially when you work with a band and spend a few weeks on something and decide, “Nope, this isn’t cutting it.” But things don’t always have to start out as esoteric to become esoteric. And as my friend Nick Cave says, “Just do the fucking work.”

“You still have to get in and do the work. This idea that a songwriter is walking in a supermarket one day, and someone in the next aisle says something and it instantly turns into a whole song…well, yeah, well that might work if you’re Smokey Robinson!”

And alchemy can come from any stage of the creative process—writing, mixing….

Yeah. One of the positive things that comes of being around and doing this for so long is you can look back and say, “Oh, okay, that’s a song people still really like that I’m still playing in my set.” And I’ll realize that it came about from fucking about on a bass line for 20 minutes. But then there are songs like “The Headmaster Ritual” where I carried around a bit of it for a couple years, and then one day we needed a song, and I sped the fucking thing up and I heard it in a totally different way.

Neil Finn, who is a masterful songwriter, nailed it when he said: “There is no formula for writing a song. It’s a mystery. Embrace the mystery.” But you still have to get in and do the work. This idea that a songwriter is walking in a supermarket one day, and someone in the next aisle says something and it instantly turns into a whole song … well, yeah, that might work if you’re Smokey Robinson!

But in my case, and certainly in the case of something like “Spirit Power and Soul,” I really had to craft that one over weeks and weeks. So that one is an example of tenacity and staying true to a vision. If you get caught up too much in divine intervention, you’ll wander around forever waiting for some melody that no one’s ever heard before. It’s in doing the work that you get there. Loads of great artists just write and write. I mentioned Nick Cave, he does it. Thom Yorke, he does it. Isaac Brock from Modest Mouse—he would write an amazing string of lyrics and then just rinse it and start again.

We’ve talked a lot about how your songs have been part hard work, and part unexpected sources of inspiration. Do you find you have to sometimes pull away from the guitar to reignite your relationship with the instrument? Do you ever get alienated from the guitar?

No. If anything, if for some reason I was going to move to Bali and retire, it would be to play for eight or nine hours a day and really expand my vocabulary. Generally, I’ll put a guitar [on a record] wherever I can. Because y’know, when I was a kid, if you bought a Thin Lizzy record, when you dropped the needle on that record, you expected to hear guitar. But because I’m also a producer, I have to find where that guitar fits appropriately. I learned guitar at the same time that I was learning about production. I also learned how to play guitar by playing along with 45s. I never had a lesson and never bought books. So I think of myself as someone who makes records, and the way I make records is to write songs. But I love guitar records. So while I’ll try other things, I’ve also been known to turn to my band while we’re working on something and say, “This needs a new intro, because we’re a guitar band.”

The Smiths - Live The Tube Studio 1984 HD (Full Show)

At the height of their creative and performa- tive powers, Johnny Marr and the Smiths could effortlessly span mutated folk-rock jangle and deep indie-dance funk, as Marr does here with his legendary 1959 ES-355—a gift from Sire Records boss Seymour Stein.

Do you think the idiosyncrasies and individuality in your playing comes from being self-taught? What about your natural proclivities as an arranger?

As a boy, a few of my pals were into playing guitar. They were really focused on “Voodoo Chile” or on what Steve Howe was doing. But I would listen to, say, the Patti Smith Group’s Radio Ethiopia, something like “Ask the Angels,” a song that’s really simple and straightforward—just an A minor and an F—and I’d think: “That’s a really cool song, it starts with power chords, okay, that’s a little like the Who. Cool I get that.” But all of the sudden I’d notice there’s a piano playing eighth-notes that sounds like the Velvet Underground or the Stooges, so I’d end up trying to play the whole record—the guitar sand the piano—rather than just the guitar part.

I was also very into Sparks, which isn’t guitar music per se, but the way the guitar is integrated is very, “Okay, now were going to use a fucking guitar!” I was just really into the sound of records as a whole. So I thought a lot about layering and when I got a machine I could overdub on, I started layering 18 guitars. By the time I got the Smiths together I had it down to 15 while trying to make it sound like just eight.

Part of that ability to layer and not create a complete mess seems related to your acute sense of rhythm and timing. That’s especially apparent in some of the Smiths’ licks—in a single part I can sometimes hear not only Keith Richards, but Keith Richards and Brian Jones, with some Steve Cropper sixths on top and Leo Nocentelli’s right hand in the same song. Was that skill cultivated from the intellectual process of breaking down how a record works?

I found around 14 that the Rolling Stones records from the ’60s, in particular, really blew my mind. Back then, that was unusual. Because my friends were jumping around to the British pop groups—things like the English Beat. But I’d hear records like “The Last Time,” and even though I knew it was old, I just thought, “Wow, this sounds better than anything around now.” So I really studied that—really getting into those singles, how they were put together, and the sound of them. I realized that Keith and Brian were doing this meshing thing. “The Last Time” is a good example; so is “It’s All Over Now.” I really picked up the soul stuff from those guys. But a lot of the rhythmic drive you’re talking about is just my personality and plain exuberance—hyperactivity really. There’s a song on The Messenger, “Generate, Generate.” I mean, that’s really a tribute to my hyperactivity (laughs). I was quite into being hyper!

You’ve always valued art and seem to have derived a lot of your energy from the notion of a bohemian life. I was always moved by your relationship and loyalty to Manchester and what that place meant as sort of a creative organism and catalyst to your development.

If you’ve got an artistic temperament, you can find inspiration in almost any place. But yeah, Manchester being so urban and musically orientated—there was a lot to rally around. When my kids were teens, me and their mother brainwashed them into having weekend jobs in Manchester, so they knew what it was to finish their shift in the city on a summer’s night, just before the clubs were opening, when all the shop workers are starting to go to the bars and exchange ideas, and all the fashionistas are lurking around. It’s really magical. Urban life is changing and subterranean life is changing. But young eyes—they don’t know different. They don’t know that a place isn’t Cleveland in the ’70s or New York in the ’60s. They’ll make the best of it. There are always great bands coming out. Right now, as we speak, there’s some band of girls and boys getting together in Williamsburg, finding their voice—and it will be great.

The Deep Cuts: Johnny Marr’s Gear in His Own Words

Anyone that’s followed Johnny Marr’s career knows the man is a certifiable guitar addict, with a Fort Knox worth of killer vintage instruments to utilize at the turn of a whim. Marr rather religiously used his signature Fender Jaguar over the last several years, but he reached deeper into his collection for the many less quintessentially Marr sounds on Fever Dreams Pts 1-4. Marr explains what he used in great detail below.

“A lot of my gear for this record was really deliberately selected, and I really honed in on a few things. I’ve got two 1973 Les Paul Customs I used for some of the darker sounds. You hear that on ‘Receiver.’ I ran those through my old MXR Flanger and either my Marshall Plexi or my HH transistor combo. Those things were part of the stylistic structure I wanted to maintain.

I played my signature Jaguar quite a lot. But since I got more into the movie soundtrack work, I’ve used a lot more 12-string, and for that I’ve been playing a Gibson EDS-1275 doubleneck because it’s the best 12-string sound. With all that mass, and the humbuckers—and if you can get it together right—all the extra resonance from the 6-string pickups, you get all kinds of overtones. There’s a couple Yamaha SG-1000s and an SG-700 on the record, which all have the Spinex pickups but sound pretty different. I used my ’63 Jazzmaster, too.

For acoustics, I played a few guitars by Auden, a company here in the UK—a 12- and 6-string—as well as the Martin D12-28 I’ve used since the Smiths. I also used the guitar that I’ve probably played more than any guitar in my life—the red 1984 or ’85 Les Paul with a Bigsby that I played a lot with the Smiths. I got that around the Meat Is Murder album. It’s great for clean stuff. A lot of stuff that folks think is a Rickenbacker is the Les Paul tracked with my Jaguar or tracked with itself in coil (split) mode. If I want to get a little natural chorus, that guitar is perfect because I’ll put a part down with both pickups on one side of the stereo image then put a split-coil track on the other side. The effect of the same guitar with these slightly different tones helps create that sound. For whammy-stuff and dive bombs, I’ll often use a Gretsch 6120 from the Smiths days. Another big part of this album, and the movie stuff, is one of my signature Jags with a Fernandes sustainer pickup in it.

Amp-wise, apart from the HH, I used a lot of the same amps I’ve had since the Smiths: my Roland JC-120, a ’65 Deluxe Reverb, a black-panel Fender Twin Reverb that I use with the Gretsch. Occasionally I’ll use the Kemper for overdubs or a Bassman or the ’69 Marshall Plexi and Super Reverb amps I used with Modest Mouse. Effects-wise, I use a lot of Carl Martin stuff: The AC-Tone, Plexitone, HeadRoom Reverb, Delayla, and Chorus XII are all great. And I’ll use the Boss RT-20 Rotary Sound a lot, too.

I’ve gone down the weird road before. But if I can’t use all this stuff and my fingers to squeeze out the right sound, I’m either not trying hard enough, or what I’m looking for is wrong. Someday I’d like to find something that will replicate the weirdness of Johnny Thunders’ 2-string bends. But I’m always looking for something that will walk the line between musical and radical.” —Johnny Marr

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)