When you think of Slash (born Saul Hudson), several things immediately come to mind. There’s his signature top hat, his flowing curly locks, his killer solos and bluesy riffs, and, of course, the Les Paul—the iconic axe that’s been by his side since the mid ’80s when he broke ground on Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite for Destruction with timeless classics like “Sweet Child o’ Mine” and “Welcome to the Jungle.” There’s some controversy surrounding the actual guitar used on that album, with speculation that it wasn’t actually a Gibson but rather a replica made by luthier Kris Derrig. No matter the origin of that guitar, Slash popularized the Les Paul at the time when pointy-headed super strats ruled the world.

In fact, he single-handedly brought the Les Paul back into vogue, and rare models began fetching unheard of sums. With supergroup Velvet Revolver and his solo project, Slash featuring Myles Kennedy and the Conspirators, the Les Paul has remained Slash’s inseparable partner-in-crime. Gibson named Slash their global brand ambassador and has collaborated with him on 17 signature Les Pauls since 1997. So, it’s not surprising that when Gibson Records launched, Slash was the first artist they contacted.

The new album from Slash featuring Myles Kennedy and the Conspirators, 4, is Gibson Records’ inaugural release. It features Todd Kerns on bass, Brent Fitz on drums, Frank Sidoris on rhythm guitar, and Kennedy on vocals. Kennedy is also known as the lead singer for Alter Bridge. It’s less common knowledge that Kennedy is a monster guitarist with a degree in jazz studies and commercial music. In his formative years, Kennedy led Cosmic Dust, a fusion band that was the vehicle for his Frank Gambale meets Mike Stern pyrotechnics. Kennedy doesn’t play guitar on 4, but when they’re on tour, to avoid straining his voice, Kennedy locks himself in the hotel room and sheds endlessly.

Slash ft. Myles Kennedy and The Conspirators - The River Is Rising (Official Music Video)

Spirit Animals

The songwriting process for 4 began during the Living the Dream tour in 2019 in the dead time before and after shows. “It’s not a rule but I always write stuff for the next record while we’re on the road with the previous,” says Slash. “A lot of this new record was initiated in that process. In dressing rooms before the show, on the bus sometimes—though usually not on the bus because everybody is all over the place—and definitely in the hotel rooms. Because I never really go anywhere. I just stay in my room. I record stuff onto my phone—the cat’s out of the bag [laughs]. When I bring something to soundcheck and the band starts to jam on an idea, I record from the board.”

Slash is a self-taught zookeeper and has housed and cared for countless wild animals, so it makes sense that animals served as inspirations for some of the songs on 4. He got his first pet rat, a black-and-white creature named Mickey, from disco/funk legend Sly Stone. One of Slash’s anacondas, Sam, resides at the Nashville Zoo, and whenever Slash is in town, he’ll go visit him. Once, Slash snuck his mountain lion, Curtis, into the opulent Four Seasons hotel after the Northridge earthquake displaced him.

Given that history, it’s fitting that the album closer, “Fall Back to Earth,” began while Slash was on safari in South Africa at Kruger National Park, inspired by the sounds of monkeys and hippos he heard in the nighttime as he looked up at the stars in the majestic sky. “I took my guitar to the park, yes [laughs],” says Slash. “I just came up with this melody, which was the main theme of ‘Fall Back to Earth,’ and I stuck with that. I loved it because it came from a place of inspiration because of the environment that I was in.”

“For me, as a sort of semi-insecure guitar player, there are things that I did want to go back and fix, but Dave was like, ‘Come on, man.’ I was like, ‘I know, I know.’” —Slash

Kennedy, a self-proclaimed softie, also took inspiration from an animal. He wrote “Fill My World” from the imagined viewpoint of his Shih Tzu, Mozart. “It was a few years ago and I was on tour. My wife had come out to see me, and we were both trying to get home. We have a little dog named Mozart and he usually stays with friends or a dog sitter. They dropped him off thinking we’d be back in an hour or two. Unfortunately, a storm rolled in, so we basically got stuck. As the storm hit, we were freaking out because we were watching on the cameras. He was at the house by himself and the thunder and the lightning—which the dogs just hate—were just scaring the hell out of him. You could see it. It was kind of heartbreaking so I thought it would be interesting to write a song from his perspective. What might have been going through his head at that point.” At one point in the song, an audible crack in Kennedy’s voice can be heard.

Enter Dave Cobb

After the songs were written, it was time to make studio arrangements. “I talked to a couple of trusted executives in the industry that I know, and I said, ‘I’m looking for a good rock ’n’ roll producer,’” recalls Slash. “And, of course, the list was very short. I had four guys to look at. Two of them were interesting, two of them were, no.”

Grammy-winning producer Dave Cobb easily got the gig. “We just talked about records we loved,” recalls Cobb. “We talked about how records used to be made where you came into the room and recorded to tape with no separation and played as if you were a band playing live instead of making it a big procedure. And that’s how we hit it off. I remember growing up and learning how to play guitar, and Slash was huge to me. I was a little nervous to talk to him.”

TIDBIT: Slash and his band, Myles Kennedy and the Conspirators, recorded 4 at Nashville’s iconic RCA Studio A. Dave Cobb produced the album, which is also the inaugural release for Gibson Records.

“He wanted to record a rock band live in the studio and I wanted to be a rock band that recorded live in the studio, so we hit it off right away,” says Slash. The band set up at Nashville’s RCA Studio A, a legendary space that Chet Atkins’ built where every country music luminary from Dolly Parton to Waylon Jennings has recorded. “The vibe in that place is so inspiring, I have to say … everybody’s recorded there,” says Slash. “Steve Cropper’s got an office upstairs. I never got to meet him but just the fact that he was in the building was just so cool.”

Guitars, bass, and drums were recorded live in one room, and Kennedy did his vocals live in an adjacent booth. Everyone was at ease, just rockin’ out, which made for a particularly stellar vocal performance from Kennedy. “I thought I was just laying down vocals for scratch tracks. I thought I was just helping guide the band, so they know, ‘Okay we’re on the verse, or we’re on the chorus.’ Then I assumed that in a week or so we’d go in, and I’d re-cut the vocal,” says Kennedy. “But Dave was happy with them. That’s the way they get a singer to relax—tell him it’s just a scratch track (laughs).”

Cobb’s ability to embrace the moment also relaxed Slash’s usual quest for perfection. “For me, as a sort of semi-insecure guitar player, there are things that I did want to go back and fix, but Dave was like, ‘Come on, man.’ I was like, ‘I know, I know,’” Slash says.

Slash’s Gear on '4'

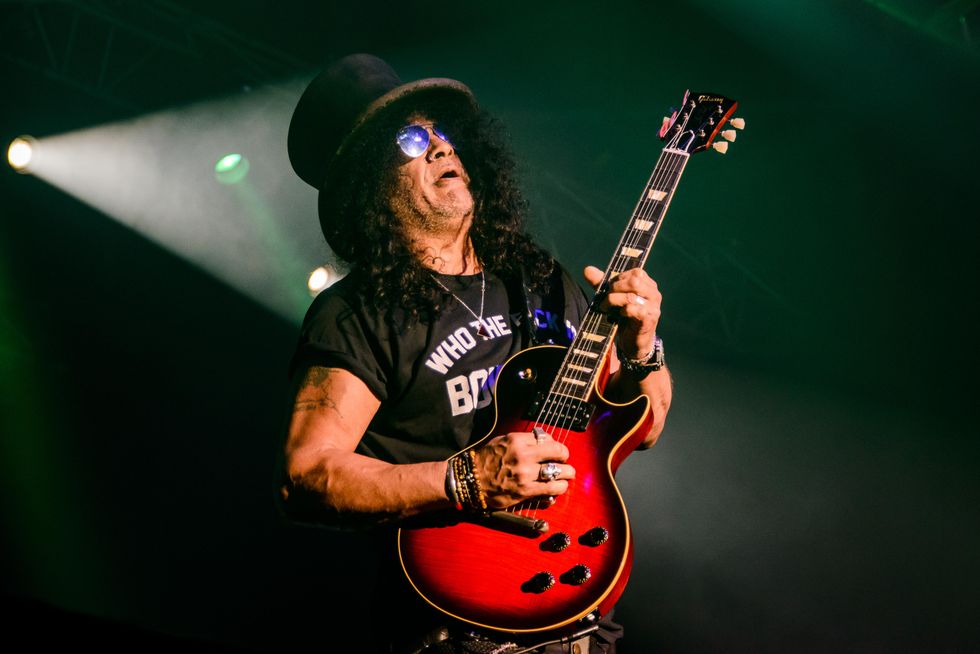

One of the most expressive combos of all-time: Slash and his inseparable Les Paul. He wrote one of the songs from 4 while at a game park in Africa. “I took my guitar to the park, yes,” he says with a laugh.

Photo by Annie Atlasman

Guitars

- Gibson ’59 reissue Les Paul (2)

- Gibson ’68 reissue Les Paul Custom

- Gibson ’69 reissue Flying V

- Kris Derrig Les Paul replica (1986)

- Most of Slash’s guitars are outfitted with his signature Seymour Duncan APH-2 Alnico II Pro Slash humbuckers

Strings & Picks

- Ernie Ball Slash Signature (.011–.048)

- Dunlop custom picks 1.14 mm

Amps

- Marshall Silver Jubilee 2555 JCM Slash Signature 100-watt head

- 1960 Marshall 4x12 cabinet loaded with Celestion Vintage 30s

Effects

- MXR EVH Phase 90

- MXR CAE Boost/Overdrive

- Dunlop Heil Talk Box

- Hammond Leslie

- Hughes & Kettner Tube Rotosphere

Dangerous Times

When Slash was in Guns N’ Roses, they were called “The Most Dangerous Band in the World” because of their hedonistic excesses. Now, older and wiser, Slash isn’t quite as carefree. For the recording session, to avoid public exposure and reduce the chance of getting Covid, the band hired a tour bus to bring them from Vegas to Nashville.

The bus first picked up Slash in L.A. and brought him to Vegas, where most of the other band members live. Myles drove into Vegas from Washington. Upon arriving in Sin City, they met up at a clinic, and after all testing negative, got on the bus and headed to Nashville. After a night’s rest, they got straight to business the next morning. At a breakneck rate of two songs per day, 90 percent of the record was done in five days. And then on the sixth day, when Slash was gearing up for some guitar overdubs, he got an unexpected call from Kennedy.

“He called me on my cell phone, which was odd to begin with,” recalls Slash. “Then he said that he had tested positive. Because we had to do regular testing, I was like, ‘Oh fuck.’ I couldn’t understand how that could possibly have happened because we hadn’t gone anywhere. Consequently, Brent, Todd, and one of the engineers at the studio were positive as well.”

Slash is synonymous with vintage Les Paul guitars and has collaborated on 17 signature models since 1997. Here he’s playing a ’59 reissue at the Fillmore Detroit with Myles Kennedy in 2015.

Photo by Ken Settle

Kennedy was also baffled. “The first time we tested was like three days before we got there and the next time we tested was the morning we walked into the studio. Everybody was fine and I was fine,” Kennedy recalls. “Then about 24 hours later I started to notice some strange symptoms. I thought they were allergies initially and, especially since I just tested, I thought, ‘There’s no way it’s Covid.’ But unfortunately, as the symptoms continued to evolve, I realized it was something a little more serious.”

Everyone had to go into quarantine, but that didn’t mean the music making had to stop. “I started to do what little guitar overdubs I had—I had some harmonies, and some sitar parts,” says Slash. “Then two days later I tested positive. It was inevitable because we were all living in the same house and sharing a communal kitchen. The house was now effectively called ‘Covid Manor.’” Only Sidoris avoided getting Covid.

Luckily, the setup of their accommodations made it possible to quarantine and still be productive. “It was perfect,” says Kennedy. “I had a little separate house outside the house. I think it was like a pool house or something. I ended up recording Todd’s vocals because Todd ended up getting sick as well. He would come out during the day, and I would set up my DAW and we would do the backing vocals.”

“Spirit Love,” “Whatever Gets You By,” and “Fall Back to Earth” were all finished in the pool house, and then the files were sent to Cobb.

“Seeing him actually in the studio, it was a ‘Holy Shit’ level of guitar playing. I knew he was incredible, and I knew he was a legend, but he’s way better than that when you see him in person.” —Dave Cobb

Dumble Destiny

Cobb’s gear inventory is impressive, and during the sessions Slash crossed paths with a true bucket-list item. “It was the first time I consciously knew I was playing through a Dumble amp. I’ve been hearing that name forever, but I didn’t know what it was,” admits Slash. “[Cobb] introduced me to a Fender that Dumble had customized, and it sounds fuckin’ amazing. I didn’t actually record anything with it, but it just sounded really good.”

Cobb recalls, “You know, Slash sounds good through a lot of things. He sounded great through that Dumble. When he plugged into it, it sounded like Slash—rock ’n’ roll, over the top, classic. It sounded like a great rock ’n’ roll amp when he played through it.”

Sadly, Alexander Dumble passed away in January, a few weeks after this PG interview with Slash took place. It seems almost like fate that their worlds collided shortly before Dumble’s passing. Slash commissioned Dumble to build him an amp, which may be one of the last projects the famed builder completed. “I got in touch with Alex after the session and he actually did a Fender for me,” Slash says. “It sounds really great. He’s not easy to get in touch with or to get him to do something, it became very apparent. So it was an honor to have him do something for me. But I didn’t know the history before. There was some discrepancy over the cost of it for a second, but he and I got to be good friends as a result of that. I didn’t know how much it cost, I thought five meant five-hundred bucks [laughs].”

Photo by Annie Atlasman

While Slash enjoys his Dumble amp—the new discovery—he stuck to a tried-and-true formula for 4. His iconic Marshall Silver Jubilee 100-watt heads into a 4x12 straight cabinet with Celestion Vintage 30s was the rig of choice.

For guitars, Slash had his staples at the ready. “I used my Kris Derrig replica, which is like my go-to guitar for recording,” he says. “But I also used a ’69 reissue Flying V, which I got last Christmas, that sounds great on a couple songs. I used two ’59 reissues, one apiece on two different songs, a ’68 Custom reissue on one song, and that was basically the setup.”

As Cobb put it, it doesn’t really matter what the gear is: Slash is going to sound like Slash. “Slash’s tone—the way he plays through a Silver Jubilee—is the ideal tone for Slash, you know what I mean?

“I’ll tell you what’s really cool. I know from being a fan, how good he is as a guitar player, and as a writer, and all of that,” Cobb continues. “But seeing him actually in the studio, it was a ‘Holy Shit’ level of guitar playing. I knew he was incredible, and I knew he was a legend, but he’s way better than that when you see him in person. I mean the solos on the record are live and he’s going for it, and it came out so classic and timeless. And his playing has so much feel and heart and soul. I didn’t realize how much better he is than I even thought he was. That was probably the biggest revelation. When he plugs in, it’s like, “I know why he’s Slash.” I was in the room with the engineer and the assistant in the control room, and we were all like, ‘Holy shit. This is way bigger and better than we even thought it was going to be.’”

Slash ft.Myles Kennedy & The Conspirators - Anastasia | Live in Sydney

Slash is a master of coaxing an impressive array of sounds out of his beloved Les Pauls. In the intro to “Anastasia,” he gets an acoustic vibe by using a fingerstyle approach combined with the Les Paul’s rhythm pickup setting. Once the distortion kicks in, he launches into a post neo-classical, pedal-point riff, before launching into all-out carnage once Myles Kennedy’s vocals enter.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.