With his latest album, Time and Emotion, Robin Trower reaffirms the promise he made when he first went solo more than 40 years ago: keep searching, keep pushing, and above all keep rocking, wherever the journey takes you.

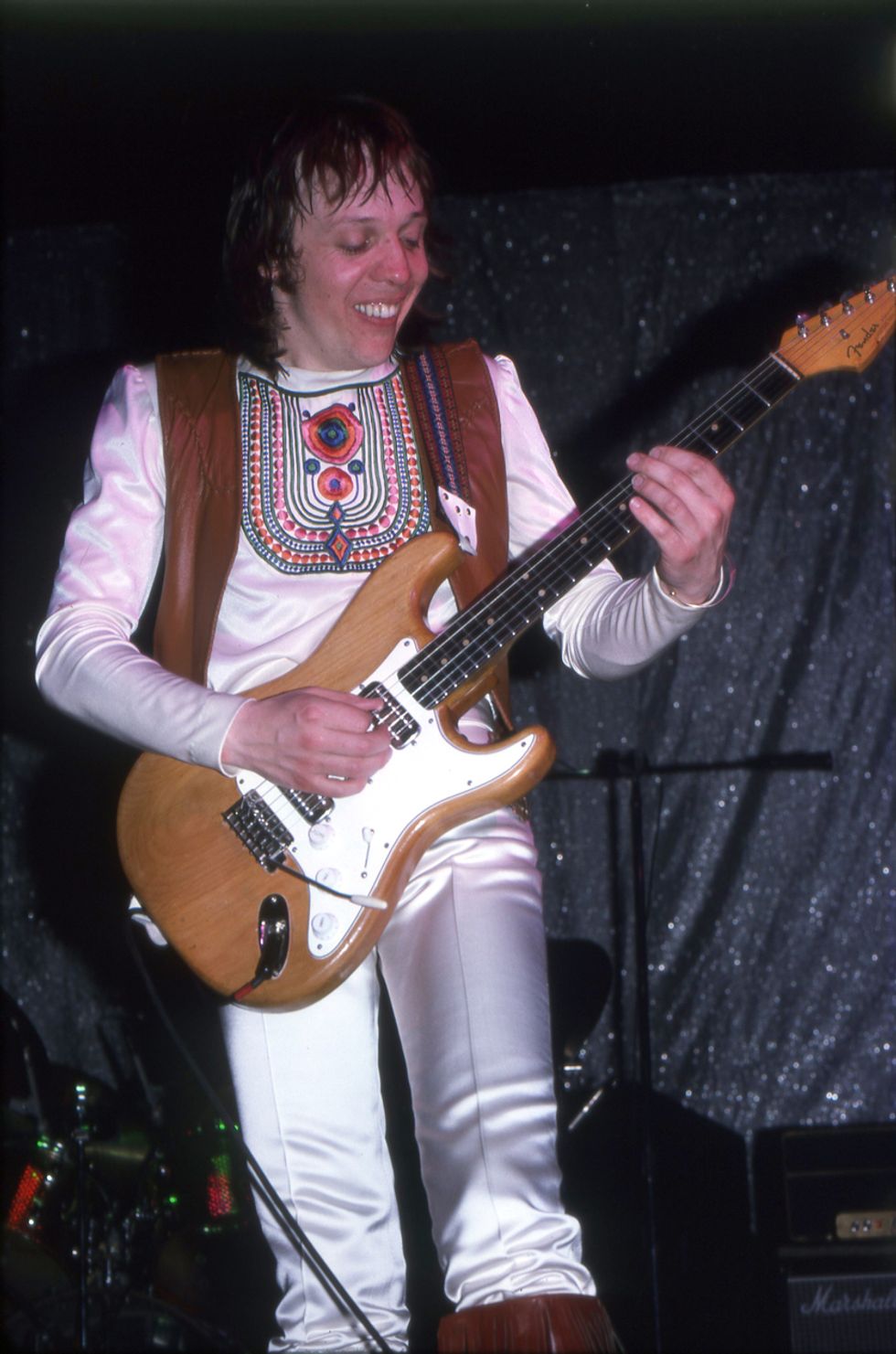

Guitar heroes aren't made—sometimes, as the saying goes, they're cornered. Trower ought to know. In the early 1970s, when he left the British rock outfit Procol Harum to launch his solo career, he was immediately hemmed in by comparisons to Jimi Hendrix. Rock critics dismissed him as an “imitator" of Jimi's sound and playing style, and to a superficial extent, they had a point. Trower was an avowed fan—he'd seen Hendrix up close for one of his last gigs, a September 4, 1970 festival date that Procol Harum shared with the Jimi Hendrix Experience in Berlin, and it wasn't long before Trower ditched his Les Paul for a Fender Stratocaster, a Marshall stack, and various Hendrixian effects (Uni-Vibe, Fuzz Face, and wah). But beyond the gear, there was a deeper dimension to Trower's musical path that just couldn't be chalked up to mere idol worship.

“There's no doubt that Jimi Hendrix was a huge influence," he concedes today. “You've got to remember, when he came along, it was a bit like when James Brown came along. There had never been anyone like that before, so what he was doing couldn't be ignored—that was the thing about it. And obviously, from that influence, I parlayed it into what I had to say myself. But it was never a matter of learning Jimi's licks or anything like that. I knew that was a non-starter. I think it was more his funky, soulful, and very atmospheric vibe, like what he was doing on Electric Ladyland. That's what got me, definitely."

what they're doing."

It's not hyperbole to assert that Time and Emotion, Trower's 25th studio album, is one of the best records he's made since his '70s heyday. As usual, the trio is his preferred format (with bassist, keyboardist, and co-producer Livingstone Brown and drummer Chris Taggart), but Trower takes on the lead vocals and a lot of the bass duties himself, and makes heavy use of overdubs to lend even more movement, fluidity, and volume to the guitars. From the sidewinding opener “The Land of Plenty" to the bluesy, Albert King-influenced “Returned in Kind," this is Trower at his most introspective and spiritual, his solos and riffs economical yet rippling with emotion, all with the intent of forging an atmosphere, of crafting an experience, that lingers long after the music ends. And at 72, Trower still feels like he has plenty more to explore.

“I think I'm always looking for something," he says, a hint of amusement in his voice. “Sometimes I'm not quite sure what, but you just have to keep pushing. When I started working on this album, I had it in my mind that it would be a bit more complex—not necessarily with the sound, but with the songwriting. Atmosphere and mood are very important ingredients in that. Not for every song, but it's a big part of what I'm looking for—to create that feeling coming off the music so a listener can get lost in it. If something soulful comes across in the music, that's exactly what I'm hoping to achieve."

Of course, there are connotations to the title Time and Emotion. What does that mean for you?

Well, I felt that song in particular stood out for me as far as the story I was trying to tell. In general, I'm definitely drawing on my experiences with my lyrics on the last few albums, and as they've become more personal, that's why I've felt I had to sing the songs myself.

Trower co-produced his 25th studio album with bassist and keyboardist Livingstone Brown. “When I started working on this album," Trower says, “I had it in my mind that it would be a bit more complex—not necessarily with the sound, but with the songwriting."

I really started to get serious about it maybe three albums ago. I was writing a lot of lyrics that were very personal, so I thought that I ought to be singing them to bring over the correct viewpoint and emotion. And I liked that the tracks were starting to sound like one voice. Even though I've worked with much better singers than me, I like the character being “all of one" with the whole thing, if you know what I mean. That's really why I got into singing more.

There's always been a real lyricism to your solos, too. Very often they sound like their own composed pieces of music. Do you have any set method to how you approach a solo?

Before I go in the studio, I'm trying to get a handle on where I would like the lead work to be, but I don't really plan much further than that. I get a flavor in my mind about what I could play, but more than anything, the main thing is to have a blast doing it and let it rip. I'm not sure I really have concrete ideas going in. I just sort of go for it, but I do feel like, in the end, it has to work as a composition, too. Basically, it's like you're trying to compose a great melody, you know? And for me, it's about being as soulful as I can make it.

“I've got a good sense of getting to the nitty-gritty as a player," says Trower, “so maybe I've pared away a lot of superfluous stuff. I can get to something I can put my heart and soul into a lot easier now."

Photo by Laurence Harvey

How did you and Livingstone Brown set about laying down the tracks for this album?

It always starts with a guitar part. I'd get the guitar down to a click—basically a drum machine—and then do a guide vocal, and then probably put the bass on myself. So I've got to have that part worked out pretty early, because everything else goes up from there, and then the drums are added later. The basic tracks were all cut at Livi's studio, and then I went back to Studio 91 [in Newbury, Berkshire, England] to do the lead work. Quite often, I revisit the guitar parts after the drums have gone on, and it's quite nice to sing it last, as well. I mean, to have the whole song on there when you're singing—that's pretty important.

Have you played bass as long as you've played guitar?

No. I only really took it up about three albums ago. I just started to come up with bass parts, and I was happy with what I was doing, so I carried it through. I bought a couple of Fender Precisions some years ago, and I'm using one of them. They're both reissues—not vintage—and I think I used a Marshall [VBA] 400 stack to record them. On a couple of tracks, I got Livingstone to replace the bass because I wasn't really up to being able to play the part I'd come up with. It really needed the proper player to do it right. On “You're the One," for example, the bass was the last thing to go on there, because we did it in the mix.

You've worked on your tone for a long time, and it has remained very consistent. What are some of your secrets behind that?

Well, I've always maintained that to get a decent sound out of the guitar, especially a Strat, you have to get a good acoustic sound. I have quite a high action, so you're getting more resonance. It's important to get that from the start, before you even amp it up or put it through a pedal. That's one of the reasons why when I chose what I would have on my signature model Strat, I went for the bigger headstock because I thought that might add a little bit more resonance—a bit more wood. All these little things add up when it comes out the amp—the tuning, the heavier strings, the higher action—but also for many years now, I've only played through overdrive pedals made by Fulltone. So it's a matter of the way the Strat is set up, using the various Fulltone pedals, and a Marshall amp.

You also tune down a whole-step, which adds a lot of depth to your tone.

That's so I can use heavier strings on the top two and get a bit more of a fat tone out of them. And if you're going to use heavy strings, you've got to tune down anyway so you can bend them and vibrato them—that's the thing. You do get a fatter sound out of it. If you use a normal gauge on a Strat, the top two strings always sound a bit slinky.

Robin Trower's Gear

GuitarsFender Custom Shop Robin Trower Signature Stratocaster with Custom '54 (neck), RW/RP Custom '60s (middle), and Texas Special (bridge) single-coil pickups.

Amps

Marshall Bluesbreaker 2x12 combo

Marshall 50-watt MK II 1987x reissue head with 2x12 or 4x12 cabinets

Effects

Fulltone Deja-Vibe

Fulltone Soul-Bender

Original Fulltone Full-Drive

Fulltone RT Signature Overdrive

Fulltone OCD V2

Fulltone Clyde Wah

Fulltone WahFull

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball custom set (.048, .036, .026, .017, .015, .012)

Dunlop 483 heavy celluloid 1.0 mm

What's the main Strat that you're playing on this album?

Actually there are two different ones, and even though they're built to my specifications, each one has its own character. I think that's more to do with the wood it's made of than anything else. But there's a Pacific Blue Strat I play on most of the album, and just as an aside, Fender is putting out my signature Strat in that color, too.

When you and the Fender Custom Shop's Todd Krause worked together on your signature Strat, what did you talk about as far as the specs were concerned?

It was pretty straightforward. It uses quite a flat radius on the neck, with jumbo frets and the bigger headstock, as I said. I wanted the vintage saddles and the tremolo arm, and a 5-way switch. With the pickups, we were going for a pretty specific sound.

The neck pickup is a '50s reissue, the middle is a '60s reissue, and the bridge pickup is what they call a Texas Special. The thing is, I'm on the neck most of the time, and with that '50s pickup, it's quite light-sounding and low output, so you get a nice lot of top end and a lot of the strings.

How did you first hook up with Mike Fuller at Fulltone?

Well, the earliest pedal I got from him was in '93, I think. That was a very early Full-Drive, with three controls on it, and I still use it now and again. In fact, I was using it on the whole of the last tour until the end, when he sent me a new OCD [Obsessive Compulsive Drive V2], so I switched to that. I really like it and I'm using that at the moment.

Eventually, Mike came up with the idea of making an overdrive especially for me. I was using that for years [since 2008], and I still go to it in recording, but on the last tour I didn't use it. I went back to the original Full-Drive because it's got a more open sound, which suited the rig better for some reason. But this new OCD is really good, very smooth. So yeah, I'm switching about all the time.

Back in 1975, Trower played a Strat with humbuckers, but these days his signature model Strat sports a trio of carefully calibrated single-coils he selected with the help of Todd Krause from the Fender Custom Shop.

Photo by Frank White

You've said that B.B. King and Albert King rise to the top for you. After all its evolution as an art form, are there any limits to where the blues can go?

Well, it's a difficult thing, because all the real blues guys have more or less passed away now. Most of the giants have gone. I don't really think of myself as playing real blues. I just think there's a lot of blues influence in what I do. I'd rather think about it in those terms, because if we start comparing it to what I call real blues, then I'm wasting my time. It's just nowhere near it. You know, a song has to stand up. Whatever label you might put on it, it has to have some strength to it. I mean, there are songs like “Make Up Your Mind," where the blues influence is very obvious, but the same thing applies to that as applies to every other track on the album. I've tried to make them as emotional as possible. That's the overview, anyway.

There's been a lot of speculation recently about the death of the guitar and rock music in general. Guitar sales are down and there's a glut of guitar makers out there. Are we losing our guitar heroes?

To be honest, I think kids aren't picking up on the guitar because it's too hard, you know? It's too hard to get really good. There are plenty of young musicians that can bang away and make it sound good, but to take it to another level is very hard work.

What would you tell a young player just starting out?

I know that almost every way you play, you'll be trying to play like someone you really admire. But my advice would be not to do that. It's impossible not to be influenced by people when you really love their playing or their music, but my advice would be not to copy what they're doing, and not to learn their lead licks note-for-note, because that can put up a block to your own creativity.

You know, on the guitar, the hands do tend to go to set places. Once you've learned somebody else's stuff, that can never be your music. That's their music. I was lucky enough when I started out to realize that. Even though I was a big fan of B.B. King in the early '60s, I was more interested in the emotion behind the notes, rather than what he was actually playing technically. I think that's the thing. You've got to find your own way to express your own emotions.

That really comes through in a song like “Returned in Kind." It's just locked in this dark, funky pocket with a lot of bluesy imagery seeping through.

I actually think that's the best thing I've ever done, and it's certainly my favorite song on the album. Well, I've got two favorite tracks—the other one is “What Was I Really Worth to You," but I think “Returned in Kind" is the best. The actual chord sequence is one of those things—like everything I write, I'm feeling around on the guitar and I stumble across something, and it goes on from there. With the lyrics, I don't know where I got the first line—it just appeared. Then I started to work on it from there. You know, I'll spend anything up to three days working on one lyric, and I'll just concentrate on that. And with the chorus “All that was given shall be returned in kind," there's nothing original about it, but I think what I'm saying is whatever you do, you're gonna get back. If it's bad, that will come back on you, and if it's good, that will come back on you in a better way.

It's one of many songs on Time and Emotion that has a real groove to it.

It gets under your skin.Well, that's a big, big thing in my playing. When I first come up with a musical idea, they always have, as you say, a pocket. And making sure that it's still there at the end when the track is finished is the key thing, really. It's good that it's emotionally strong, but it's also got to move you.

YouTube It

This multi-camera, full-concert video captures every nuance of Robin Trower's trademark vibrato, biting riffage, and fluid, Uni-Vibe-drenched chording. Packed with extended, close-up shots of his fretting and picking hands, it's a masterclass in how to make a Stratocaster sing.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)