In the early 1980s, Austrian guitarist Wolfgang Muthspiel moved to Boston with something of a split musical identity. He went to the New England Conservatory and divided his time between jazz studies with legendary guitar instructor Mick Goodrick and classical lessons with noted composer, player, and teacher David Leisner. With Goodrick, Muthspiel flatpicked electric guitar and focused on jazz theory and improvisation, while with Leisner he embraced traditional classical technique and repertoire.

But for Muthspiel, the Conservatory proved to be a crossroads: By 1986 he'd not only transferred to Berklee and committed completely to jazz, but also started gigging, taking the coveted spot in noted vibraphonist Gary Burton's touring band—a gig akin to a rock shredder being invited to hit the road with Ozzy Osbourne. Other notable guitarists to hold that chair include Pat Metheny, John Scofield, and Julian Lage. And he began a decades-long musical collaboration playing in duos with Goodrick.

Although Muthspiel planted his flag firmly in the jazz camp, he never abandoned the nylon-string classical guitar. His live performances and recordings still feature him alternating between electric and acoustic, and he maintains a sense of purity to each approach. He plays acoustic guitar seated, sans amp or effects, his manicured nails hovering above the soundhole, while for electric-guitar pieces he stands, using either a flatpick or a hybrid picking technique, and runs his signal through a battery of pedals, loopers, and usually a Vox AC30.

But switching instruments is just one facet of what Muthspiel does. His discography includes more than 40 albums as a leader, and many other appearances as either a collaborator or sideman. He's also an accomplished composer and improviser, comfortable in multiple jazz idioms—from hard bop to free jazz. And although his core group is a trio, he's not afraid to experiment with other types of lineups.

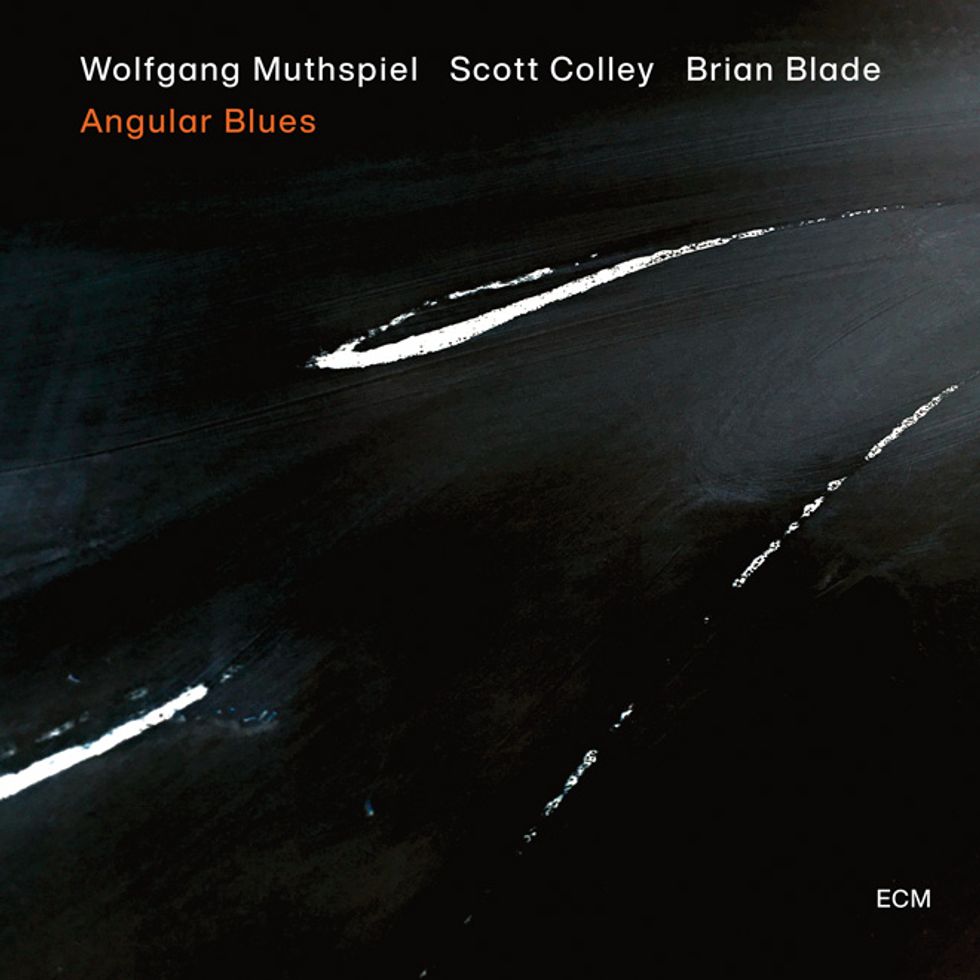

Muthspiel's most recent trio release, Angular Blues, features bassist Scott Colley and drummer Brian Blade, and is both forward-looking and traditional. The 55-year-old shows off his technical prowess on the angular, intricate, and harmonically challenging title track, and blows through choruses on “Ride," his first time recording bop-style "rhythm changes" tune for ECM. The album features two “Kanons"—one in 5/4 and one in 6/8— which incorporate his unique approach to delays in a classical-style contrapuntal round. The album's overall sound conforms to the ECM playbook as well: recorded live with minimal edits and pristine fidelity. And while Muthspiel didn't fly his hefty AC30 to the Tokyo studio where Angular was tracked, they had a vintage Fender Princeton on hand that did the trick.

We spoke with Muthspiel just as it was becoming clear that his spring tour of the U.S. was about to be canceled. We discussed his apprenticeship under Burton and Goodrick, the distinct phases of his recording career, his never-ending fascination with loopers and delays, the intricacies of right- and left-hand technique, his long-term relationships with luthiers Nico Moffa and Jim Redgate, and why he still keeps his approaches to the electric and acoustic guitar separate.

Did you start as a classical player?

I started playing violin when I was 6, and I started playing guitar when I was 12. My whole first years, until I was about 14 or 15, were spent with classical music. Then I discovered jazz, got into it, and started playing electric guitar. I listened to Ralph Towner and people like that who made a bridge to the improvised world, and I went that way. I kept both things up, classical and jazz, until I was 22. I went to the States and studied in Boston with Mick Goodrick, who was at the New England Conservatory and teaching jazz, and David Leisner, who was teaching classical guitar. I went to Berklee two years later, because I had decided to go for jazz all the way, and then I met Gary Burton and so on. But the jazz and classical thing was parallel for a while.

Your studies with David Leisner were straight classical?

Totally. I was playing concerts with classical guitar and doing competitions and all that stuff. It's a small repertoire of really great music. There is a lot of great music you can play on the guitar, but strictly classical written music, some of the top guys have not written for the instrument. You have that wonderful lute stuff that Bach wrote, and all the great Renaissance lute music that you can play on guitar, and then some really cool modern music, but it is not such a big pool of music as compared to violin or piano. That also contributed to my decision to go all the way into jazz.

How long were you with Gary Burton?

I was playing in his band for two years, and it was an amazing thing for me to be hired by him. We toured quite a bit. I was still studying at Berklee, but we toured a lot in the States. That was a nice band. I met bassist Larry Grenadier in that band for the first time—who I played with a lot up until now—and Don McCaslin was on saxophone. Gary is a very clear and strong leader, and very supportive. It was really a good experience for me.

Did you start recording around that time as well?

My first record under my own name was a trio album that I recorded in the States, but I already did some recordings before, with my brother. The first phase of my improvised music was together with my brother, Christian, who's two years older. He is a pianist, trombonist, and composer, and we played together at home with every instrument that we had—with all the tools and toys we could find. We didn't know anything about jazz then, but it was the start of this kind of improvised music. My first records I did with him. But I did a trio record on my own, and Gary Burton was really helpful. He produced another album for me, where I could pick and choose who I played with. That was a great thing. He was generally really supportive. Him and Mick Goodrick, who was also a huge guy for me.

TIDBIT: Muthspiel says ECM's approach to recording is “an aesthetic where the natural flow of the improvisation of the musicians is captured as well as possible. It is about the moment—to catch the moment of the jazz musicians' conversation."

Mick was a strict, tough, great teacher, and, at the same time, we had a duo going on. Eventually we made a record much later. He has many cool approaches to harmony, and to the fretboard. Mick has a mathematic brain, and also a philosophical brain. He's thought very deeply about the instrument his whole life, and he knows how to communicate that to students. He was such a legendary teacher. He taught a lot of great players, and he was a fantastic influence.

How has your approach to recording changed since you started?

I had three periods of recording. One was for a label called PolyGram, which later became Universal. That was a certain era of recording, and there was a lot of [sonic] separation. There was an aesthetic of a certain sound—everyone was so proud of the highs and the crispness—and everything was super thin and sharp. It was not favoring the most organic, acoustic vibe.

Later, I founded my own label, in 2001, which is called Material Records. On this label, I've done about 45 records. Some are mine, but also from other people. That was another era of recording for me, where I could do whatever I wanted. I didn't have to ask anybody what I should record, but, at the same time, I also ran into restrictions.

What sorts of restrictions?

In order to really place a record in the world, it needs more than a good recording. It needs a network and a plan behind it, and people who will distribute it and promote it. I didn't have that with my record label, so those were years where I made a lot of records but they were not that much noticed. Then I got to ECM, which was the label that influenced me most when I was young. When I was getting into jazz, my heroes were on ECM. This is the last period, so to speak, with ECM.

How would you describe your experience recording for ECM?

ECM has a very conscious approach to sound and recording. It's an aesthetic where the natural flow of the improvisation of the musicians is captured as well as possible. It is about the moment—to catch the moment of the jazz musicians' conversation. It is not about editing or creating layers of tracks. It's like a very well-recorded live concert. That's due to the character and taste of Manfred Eicher, who built the label.There is some editing possible, but not with single instruments. You can edit a whole section away of everybody, but you can't go in and change a note, because it is recorded without separation, and everything bleeds into each other. It isn't only the technical aspects of it, but it is another attitude as well. It's like in a concert. It counts from the first note to the last, and that is a nice vibe. Also, the people I have been playing with on the last five records, which are on ECM, this is what they do. This is their game—what they're good at. Sometimes one take doesn't work, so you do another one, maybe with a different approach, but you don't splice together an album. That is not a bad thing in itself, by the way. There are some heavily edited records that I love. But it is not the way ECM does it.

This nylon-string classical guitar was made by Jim Redgate, who builds about 20 instruments each year in his solar-powered workshop in Australia. Photo by Scott Friedlander

Do you use the same gear when you record versus playing live?

I use the same guitars, for sure. Regarding the amp, if I can manage to bring the amp to the place where we're recording, yes, and if not, I make sure they have something that I really like. The last album, Angular Blues, was recorded in Tokyo. They had an old Fender Princeton in very good condition, so that was great. Normally, I have an older Vox AC30 that I like to use.

Do you play acoustic guitar using classical technique, and do you care for your nails like a classical player?

Absolutely. I have to—otherwise my sound is not happening. Every time you play for a few hours, your nails need some filing again so that the sound stays well. I do some simple things every day on the classical guitar just to keep that sound.

Do your nails get beat up when you fingerpick on your electric?

Yes, they tend to. On the electric, when I am playing lines, I pretty much use the pick. But with harmony and counterpoint, I use my nails. I play differently on the electric for sure. On the acoustic guitar, I have a technique where I pluck the string kind of hard, with an apoyando, where the finger rests on the next string after the stroke. It's like how the flamenco guys play. That's a technique that you can't use on the electric. For me, acoustic and electric are two quite different animals. I love both of them, but they need a different technique.

You must have been older when you first started using a pick.

Exactly. I was already playing quite fluently before I played with a pick, and I had to learn the whole pick thing from scratch.

Your left-hand technique appears to stay the same on acoustic and electric, though—you seem to keep your thumb in the center of the neck, which is a more traditional approach.

I would say so, yes. At this point, I am not consciously putting my hand in a certain way. But, of course, my whole first years were classically trained, so that stayed. Also, when the fingers come from really above the string, that is the easiest way to play with the least strength. With classical guitar, it is a little harder to press the string down, and if you don't have the right technique, your hands get tired, which is why they stress that so much. You use whatever technique uses the least pressure and muscles.

Recently you seem to use a lot of pedals when you play electric. Is that a new thing or have you always done that?

I always did and, I think early on, even more. I've been playing with loopers from the time they came out. Delays were a big sensation, and whenever a delay came out with a long delay time—it was way before the idea that you could have a loop or that you could record two minutes, it was totally out of reach—I went with all those technological steps. I also used loops a lot to practice and for solo concerts. There are two pieces on the album called kanons. One is a kanon in 5/4 and one is in 6/8, and they both use a delay with which I play the kanon. A kanon is nothing but a delay, so I figured out how to use it in that way.

Do you approach the kanon that way live, even with the band?

Yes, and in the band setting this delay that creates the kanon is tap-tempo. If the band changes tempo slightly—it's not that exact—I can tap the tempo along with my playing and I am always with them.

How does your role change playing with a trio as opposed to a larger group, like a quintet?

In the trio, I am responsible for more things—I can influence every harmonic move. It is basically a conversation with the bass and the drums, but as far as harmony and how I lay something out, it is really up to me. In the quintet, I see that we are equals in a big conversation. For example, the albums I did with pianist Brad Mehldau: Harmonically I was also letting him steer the music, and I was really enjoying being able to solo on top of his comping.

Guitars

Nico Moffa Mithra archtop electric

Jim Redgate classical

Amps

Vox AC30

Effects

Mad Professor Forest Green Compressor

Tonehunter Tasty Flakes

Boss OC-3 Super Octave

Boss DD-5 Digital Delay

Electro-Harmonix Superego Synth Engine

MXR Carbon Copy Analog Delay

GFI System Specular Reverb V3

DigiTech JamMan

Lehle switchers

TC Electronic Polytune Clip

Strings and Picks

Thomastik, D'Addario, or Elixir strings (.011 sets)

D'Addario medium-tension nylon strings

Dunlop 1.14 mm picks

When I play in a trio, only the bass comps for me harmonically, so I have to either imply the harmonies in my lines, or I have to provide them with chords. It is quite a different role. I like both, but the trio is the core discipline.

Piano and guitar have similar roles when someone else is soloing. You have to be able to navigate each other.

Exactly, which is fun and can be a great adventure, especially if you comp together. The easy way would be to say, “You comp on this song and I comp on this solo," so you don't get in each other's way. But it's much more fun to play together. If somebody's listening—and somebody like Brad Mehldau is listening very hard to everything—he would immediately react to what I do, or the other way around. Somebody would play something dense, and the other would play just a line or a tone and so on. That's a very interesting game to comp together with two harmonic instruments.

The new album has rhythm changes for a few standards, too. Is that a first for you?

It's the first time it's been recorded on ECM. I've done that for a while, of course. Getting into jazz, going to Boston, trying to learn that language, I dealt heavily with standards. When I got into jazz, I had the feeling that I had to make up for a lot of stuff that I missed when I was younger, because I was playing everything else but jazz. I knew the harmony of Bach, but I didn't know any harmony of [Duke] Ellington. I had to learn the language quickly, and standards were a big step for me. I kept them—not so much in concerts—but just for myself, and also as a teacher. But now it is nice to share that side again.

What inspired you to do that for this album?

Basically the fact that we played in a jazz club in Japan. It just felt right to add some standards. Also the fact that I played with Scott Colley [bass] and Brian Blade [drums]. Those two guys know this music inside out. It is second nature to them, and it was a luxurious situation for me.

Who built your electric?

It's built by an Italian luthier, Nico Moffa. He's been building me different ones. He's a wonderful, great guitar maker, and for 10 years we have been in touch a lot. He sends me stuff and I try it. I go to his workshop. The model is called Mithra. The acoustic guitar I play is made by a guy from Australia named Jim Redgate. In the last 10 years I've played a lot in Australia, so every time I go, I visit him, and he's another deep craftsman. For me, these relationships have become really important. The builders make them with you in mind. They listen to your music while they make the guitar. And the instrument influences the musician. If it works, everybody can learn from each other. The luthier needs your feedback and you need his guitar, so it is a good marriage.

Are the necks on your electrics built similar to a classical guitar neck?

The neck on the electric is much smaller. It's good that it is very different for me, because then I touch it and know I am in that world. It is a different thing, and my fingers react differently. When I touch the classical, it's that spacing. It is really two different instruments. Also, with acoustic guitar, I sit like a classical guitarist, and with electric guitar I stand. With electric guitar, I use a lot of effects, with acoustic guitar, none—and so on. I want to keep them two different worlds.

Based on his study of classical counterpoint, Wolfgang Muthspiel composed two “kanons" for his latest album. Here's a live trio version of his “Kanon in 6/8." Check out his use of delay and looping at 1:50 and 9:35, respectively.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)