Joe Bonamassa onstage with a Music Man Y2D outfitted with two

humbuckers, a single-coil, and a solid-brass tail block.

Joe Bonamassa, one of today’s hottest blues/blues-rock players, has enjoyed an extraordinarily charmed life—at least when it comes to all things guitar. His parents not only owned a music shop in upstate New York, they also owned a very cool record collection that turned him on to artists like Guitar Slim and Eric Clapton when he was practically a toddler. Later, they hooked him up with an enviable selection of instruments. Bonamassa proceeded to learn Stevie Ray Vaughan licks at the ripe age of 7, and by 12, as a protégé of Telecaster legend Danny Gatton, was skilled enough to open for blues god B.B. King.

Since 2000, Bonamassa, now 34, has perfected his trademark brand of electrifying blues-rock on more than a dozen albums. His searing lines and soulful vocals have proven just as popular with guitarists as with the general public. At press time, his latest solo album, Dust Bowl, had climbed to #37 on the US charts. But thanks to his insatiable playing appetite and tireless work ethic, Bonamassa has also been attracting attention in the rock super group Black Country Communion, which is fronted by former Deep Purple bassist/vocalist Glenn Hughes.

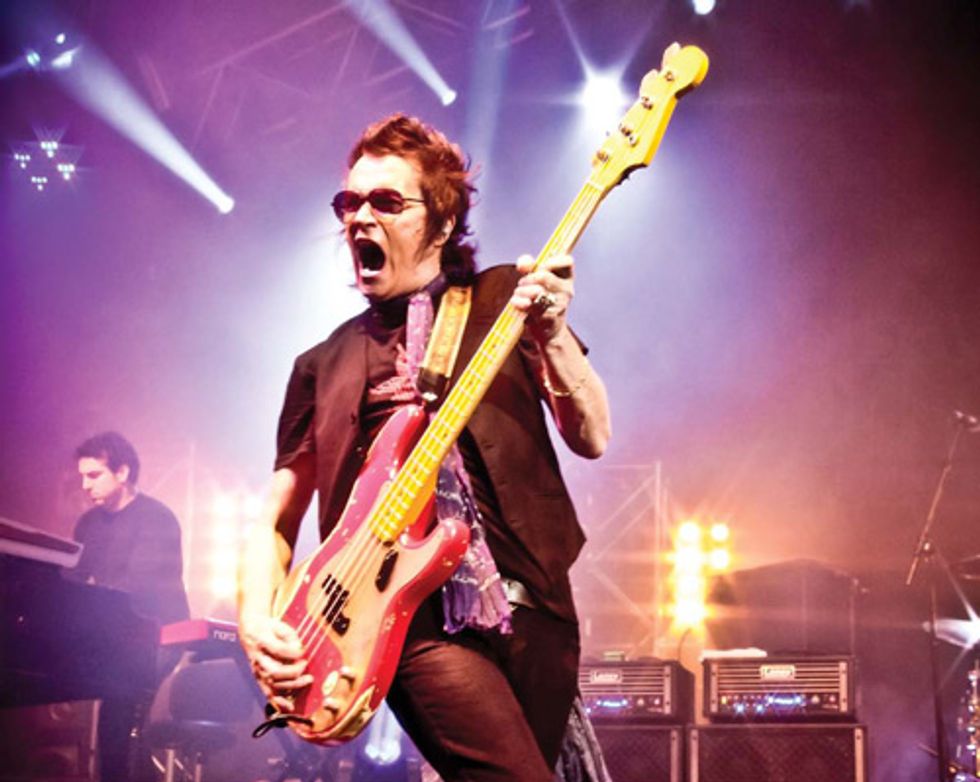

Black Country Communion vocalist/bassist Glenn Hughes wields

his Nash PB57 while Derek Sherinian pounds the ivories.

Having joined DP in 1974, and later doing a stint with Black Sabbath, Hughes had a hands-on role in shaping the heavier strains of the British blues-rock movement that is one of Bonamassa’s main benchmarks. In Black Country Communion, Bonamassa and Hughes are flanked by a pair of formidable musicians—the late Led Zeppelin drummer John Bonham’s son Jason on drums and ex-Dream Theater wizard Derek Sherinian on keyboards. On 2, the follow-up to BCC’s acclaimed 2010 debut, the Anglo-American quartet plays a tight, fierce brand of rock that shows another side of Bonamassa. We recently spoke to Bonamassa and Hughes about their new rock ’n’ roll adventures and how they approach their music.

For those who haven’t heard yet, how did you guys come to form Black Country Communion?

Hughes: I met Joe around the time that he was on the rise, about five years ago, at a NAMM show in Los Angeles. It was a pleasure to encounter this really nice lad who grew up playing my music and Led Zeppelin’s. We befriended each other immediately. Joe came over to my house a few times to have lunch and play some music, and we casually talked about making a record together. Jump forward three years, and producer Kevin Shirley [Rush, Dream Theater, Iron Maiden] suggested we get together with Jason and Derek. After that, it all happened so quickly. Within a month, we were in the studio making our first album. The rest is history.

Bonamassa (right) rocks a flamed-maple Les Paul plugged into a pair of Marshall JCM2000s and a vintage Laney Klipp head, while Hughes routes his Nash PB57 through dual Laney Nexus-Tube stacks.

Joe, what was it like to go from fronting your own blues-based band to playing in a rock super group?

Bonamassa: If someone had told me just a few years ago that I’d be in a huge rock band, I’d have said, “You’re crazy.” But that’s the way life goes—there’s no telling where it will take you. It’s such an honor to be playing in a great group with such high-caliber musicians, some of whom I grew up listening to. And it’s a very comfortable position, too, just being the guitar player—kind of a relief from fronting my own band, which I do 160 nights a year.

On the other hand, being in a band like this can occasionally be kind of like a rugby scrum. It gets kind of rough and tumble, with everyone jockeying for position and all going for it at once, as opposed to having other players take on more supportive roles in a solo context. But I think we all have a great chemistry together on account of our shared affinity for British blues-rock, and everything comes together so quickly in the studio for us, kind of like what it must have been like back in the day for bands like the Faces.

Glenn, what was it like to play with Joe—did you feel any sort of generational divide?

Hughes: Absolutely not. Joe plays with maturity beyond his years and has such a deep knowledge of, and respect for, the blues tradition. It’s very pure. But Joe’s not just a great bluesman, he’s one of those rare lads who can cross effortlessly between blues and rock, not unlike a Jimmy Page or an Eric Clapton or a Gary Moore. Most rock guitarists can’t really play the blues—it’s not in their DNA—and vice versa. And Joe’s also a consummate professional— he recorded everything mostly on one take and never more than two. I especially liked his signature sound on “Cold”—so painful, like a dying bird, but exquisitely beautiful.

|

Bonamassa: Neither, really. I like to think of myself as the Line 6 Pod of guitar players: You can set me to “Blues Breakers Clapton” and I’ll pull it off, you can set me to “British Blues-Rock 1974” and I’ll pull it off, you can set me to “Vintage Muddy Waters” and I’ll pull it off. Whatever the situation calls for, I like to think I can deliver in an authentic way.

Glenn, your bass lines on 2 are so soulful and melodic— even in such a hard-rock context. Who are your influences, and how do you go about writing bass lines?

Hughes: It all goes back to when I was a boy in short trousers living in the north of England and getting into the Beatles and, later, the Stones as a sort of rebellious thing. Then, in my late teens, I started getting excited about sounds from black America—some blues, but mostly Motown and Tamla soul records . . . players like James Jamerson and Carol Kaye. All of these sounds came together to inform my sound, and I obviously wear my influences upon my sleeve.

I’m a singer, and the bass is an extension of my voice, so what I write on the bass tends to be highly melodic. I also tend to bend the strings a lot to get a vocal-like sound. Because of that, I’ve used light-gauge strings since the 1960s, and I’ve never had a problem with them going out of tune. I’m not a hammer-on bass player—I don’t come from the ’80s school of thought, where more notes are better. In a nutshell, I write simple bass lines where what I don’t play is as important as what I do—tuneful bass lines that have a nice, old-school groove and anchor the song rather than busy it up.

What is your songwriting process like?

Hughes: It’s very natural—the cornerstone of my life, really. What I mainly do is hatch an idea for a song and watch it develop. It often begins for me late at night when my wife and I go into the bedroom, where four dogs are usually hanging out on the bed and an acoustic guitar is sitting next to it on a stand—a very relaxed environment for writing, unlike sitting at a desk and forcing myself to write. I believe, by the way, that all of the greatest songs were written on acoustic—take, for example, “Satisfaction” and “A Day in the Life.” In any case, as my wife and I wind down from the day, I’ll just pick up the guitar and play for a while, recording it onto a Dictaphone. The next morning, I’ll have a listen to the tape and see if I captured anything worth expanding into a complete song with lyrics.

For this particular album, even though I was working with brilliant improvisers, I didn’t want to just go into the studio and jam. It’s nothing against jam music—in fact we’ll probably morph into jamming a bit when we take these new songs on the road. Luckily, I had the luxury of spending about four months on writing the songs, rather than rushing something together at the last minute. I brought about a half-dozen barebones sketches, with melodies, chord progressions, and lyrics, into the studio and gave my mates permission to kick my babies around the room. That’s the way I look at it—songs are like children. It was hard to let go of them at first, but in the end I trusted everyone to add and subtract little bits and pieces. That’s the best way to do it in a band, democratically. In this case, it made my music better to share it with a group of strong individuals— which is something I hadn’t done in a long time until BCC got together.

Bonamassa: I think one of my biggest models, in terms of songwriting, is Jimmy Page. I try to take old blues music and make it my own like he did. In terms of the process, a lot of guitarists start out with licks or riffs, but I usually come up with the lyrics first—or, at the very least, the title. When it comes time to write the music, I use whatever guitar I have close by—I have about 100 in my collection—and try to come up with things that are as much about the song as the solo.

Joe, what was it like to go from fronting your own blues-based band to playing in a rock super group?

Bonamassa: If someone had told me just a few years ago that I’d be in a huge rock band, I’d have said, “You’re crazy.” But that’s the way life goes—there’s no telling where it will take you. It’s such an honor to be playing in a great group with such high-caliber musicians, some of whom I grew up listening to. And it’s a very comfortable position, too, just being the guitar player—kind of a relief from fronting my own band, which I do 160 nights a year.

On the other hand, being in a band like this can occasionally be kind of like a rugby scrum. It gets kind of rough and tumble, with everyone jockeying for position and all going for it at once, as opposed to having other players take on more supportive roles in a solo context. But I think we all have a great chemistry together on account of our shared affinity for British blues-rock, and everything comes together so quickly in the studio for us, kind of like what it must have been like back in the day for bands like the Faces.

Glenn, what was it like to play with Joe—did you feel any sort of generational divide?

Hughes: Absolutely not. Joe plays with maturity beyond his years and has such a deep knowledge of, and respect for, the blues tradition. It’s very pure. But Joe’s not just a great bluesman, he’s one of those rare lads who can cross effortlessly between blues and rock, not unlike a Jimmy Page or an Eric Clapton or a Gary Moore. Most rock guitarists can’t really play the blues—it’s not in their DNA—and vice versa. And Joe’s also a consummate professional— he recorded everything mostly on one take and never more than two. I especially liked his signature sound on “Cold”—so painful, like a dying bird, but exquisitely beautiful.

|

Bonamassa: Neither, really. I like to think of myself as the Line 6 Pod of guitar players: You can set me to “Blues Breakers Clapton” and I’ll pull it off, you can set me to “British Blues-Rock 1974” and I’ll pull it off, you can set me to “Vintage Muddy Waters” and I’ll pull it off. Whatever the situation calls for, I like to think I can deliver in an authentic way.

Glenn, your bass lines on 2 are so soulful and melodic— even in such a hard-rock context. Who are your influences, and how do you go about writing bass lines?

Hughes: It all goes back to when I was a boy in short trousers living in the north of England and getting into the Beatles and, later, the Stones as a sort of rebellious thing. Then, in my late teens, I started getting excited about sounds from black America—some blues, but mostly Motown and Tamla soul records . . . players like James Jamerson and Carol Kaye. All of these sounds came together to inform my sound, and I obviously wear my influences upon my sleeve.

I’m a singer, and the bass is an extension of my voice, so what I write on the bass tends to be highly melodic. I also tend to bend the strings a lot to get a vocal-like sound. Because of that, I’ve used light-gauge strings since the 1960s, and I’ve never had a problem with them going out of tune. I’m not a hammer-on bass player—I don’t come from the ’80s school of thought, where more notes are better. In a nutshell, I write simple bass lines where what I don’t play is as important as what I do—tuneful bass lines that have a nice, old-school groove and anchor the song rather than busy it up.

What is your songwriting process like?

Hughes: It’s very natural—the cornerstone of my life, really. What I mainly do is hatch an idea for a song and watch it develop. It often begins for me late at night when my wife and I go into the bedroom, where four dogs are usually hanging out on the bed and an acoustic guitar is sitting next to it on a stand—a very relaxed environment for writing, unlike sitting at a desk and forcing myself to write. I believe, by the way, that all of the greatest songs were written on acoustic—take, for example, “Satisfaction” and “A Day in the Life.” In any case, as my wife and I wind down from the day, I’ll just pick up the guitar and play for a while, recording it onto a Dictaphone. The next morning, I’ll have a listen to the tape and see if I captured anything worth expanding into a complete song with lyrics.

For this particular album, even though I was working with brilliant improvisers, I didn’t want to just go into the studio and jam. It’s nothing against jam music—in fact we’ll probably morph into jamming a bit when we take these new songs on the road. Luckily, I had the luxury of spending about four months on writing the songs, rather than rushing something together at the last minute. I brought about a half-dozen barebones sketches, with melodies, chord progressions, and lyrics, into the studio and gave my mates permission to kick my babies around the room. That’s the way I look at it—songs are like children. It was hard to let go of them at first, but in the end I trusted everyone to add and subtract little bits and pieces. That’s the best way to do it in a band, democratically. In this case, it made my music better to share it with a group of strong individuals— which is something I hadn’t done in a long time until BCC got together.

Bonamassa: I think one of my biggest models, in terms of songwriting, is Jimmy Page. I try to take old blues music and make it my own like he did. In terms of the process, a lot of guitarists start out with licks or riffs, but I usually come up with the lyrics first—or, at the very least, the title. When it comes time to write the music, I use whatever guitar I have close by—I have about 100 in my collection—and try to come up with things that are as much about the song as the solo.

One of Bonamassa’s favorite guitars—a 1959 Gibson Les Paul he calls “Magellan”—getting

cozy with a Native Americanthemed blanket and pillow.

A close-up of Magellan, which features a beautiful honeyburst finish and is all original except for its tuners.

Joe, you’re known as a big-time gear aficionado. What were some of the guitars you used on 2?

Bonamassa: I had something like 40 freakin’ guitars at my disposal for the record. I used a bunch of Gibson Les Pauls—some of my goldtop signature models and a real ’59 burst that I’ve nicknamed Magellan because it’s traveled around the world with me. It’s all stock except for the tuners, which I swapped out. I also played a Gibson Custom Don Felder doubleneck, an ’82 Explorer with three humbuckers like a Les Paul Custom, a Fender Jeff Beck Stratocaster, and a Music Man Steve Morse Y2D. For acoustic, I used an extremely rare 1969 Grammer Johnny Cash model.

Which amps and effects did you record the album with?

Bonamassa: I selected from a wall of Marshalls: four Jubilees and four ’69 metal-panel Super Leads that I kept powered up continuously during the sessions. For cabs, I had two old Marshall Super Basses and two Mojo cabinets, all with Electro- Voice EVM12L speakers. I made pretty minimal use of effects on the record—just a Tube Screamer, a Boss DD-3, my signature Fuzz Face, and a new signature wah-wah that was custom-made by Jeorge Tripps of Dunlop Manufacturing and Way Huge Electronics. [Ed. note: According to Tripps, the wah has a copper top with a gloss-black bottom and features a Halo inductor and full-size components mounted on a through-hole board for sweet, vintage tone.]

Glenn, what are some of your go-to basses?

Hughes: I have a number of old Fenders, but lately I’ve been playing a couple of P-bass-style instruments—one in Dakota Red and the other in Olympic White—made by Bill Nash, the great relic builder. His basses not only look realistically old, they sound remarkably like ’50s models. I’m utterly blown away by them—they work staggeringly well for me. And, in case you’re wondering, I don’t get paid to play them.

Black Country Communion—keyboardist Derek Sherinian (left), Hughes, drummer Jason Bonham, and Bonamassa—smoking onstage.

What about effects and amplification?

Hughes: I don’t use any effects in Black Country Communion. I’m pretty organic and don’t really fly with processed stuff. Instead, I plug straight into a pair of 400-watt Laney Nexus- Tube amps, which have an amazingly thick sound that reminds me of the Hiwatts I used back in my Deep Purple days.

Joe, on 2, you get a sound that could be described as metal-like in spots—like in the dropped-D riffing in “The Outsider.” Have you always been into that genre?

Bonamassa: Yes. It might not always be obvious from listening to my other music, but I’ve long been a big fan of metal for its mystery and intrigue. It makes a lot of sense when you think about it, since metal is rooted in the blues.

One of Bonamassa’s favorite guitars—a 1959 Gibson Les Paul he calls “Magellan”—getting

cozy with a Native Americanthemed blanket and pillow.

A close-up of Magellan, which features a beautiful honeyburst finish and is all original except for its tuners.

Joe, you’re known as a big-time gear aficionado. What were some of the guitars you used on 2?

Bonamassa: I had something like 40 freakin’ guitars at my disposal for the record. I used a bunch of Gibson Les Pauls—some of my goldtop signature models and a real ’59 burst that I’ve nicknamed Magellan because it’s traveled around the world with me. It’s all stock except for the tuners, which I swapped out. I also played a Gibson Custom Don Felder doubleneck, an ’82 Explorer with three humbuckers like a Les Paul Custom, a Fender Jeff Beck Stratocaster, and a Music Man Steve Morse Y2D. For acoustic, I used an extremely rare 1969 Grammer Johnny Cash model.

Which amps and effects did you record the album with?

Bonamassa: I selected from a wall of Marshalls: four Jubilees and four ’69 metal-panel Super Leads that I kept powered up continuously during the sessions. For cabs, I had two old Marshall Super Basses and two Mojo cabinets, all with Electro- Voice EVM12L speakers. I made pretty minimal use of effects on the record—just a Tube Screamer, a Boss DD-3, my signature Fuzz Face, and a new signature wah-wah that was custom-made by Jeorge Tripps of Dunlop Manufacturing and Way Huge Electronics. [Ed. note: According to Tripps, the wah has a copper top with a gloss-black bottom and features a Halo inductor and full-size components mounted on a through-hole board for sweet, vintage tone.]

Glenn, what are some of your go-to basses?

Hughes: I have a number of old Fenders, but lately I’ve been playing a couple of P-bass-style instruments—one in Dakota Red and the other in Olympic White—made by Bill Nash, the great relic builder. His basses not only look realistically old, they sound remarkably like ’50s models. I’m utterly blown away by them—they work staggeringly well for me. And, in case you’re wondering, I don’t get paid to play them.

Black Country Communion—keyboardist Derek Sherinian (left), Hughes, drummer Jason Bonham, and Bonamassa—smoking onstage.

What about effects and amplification?

Hughes: I don’t use any effects in Black Country Communion. I’m pretty organic and don’t really fly with processed stuff. Instead, I plug straight into a pair of 400-watt Laney Nexus- Tube amps, which have an amazingly thick sound that reminds me of the Hiwatts I used back in my Deep Purple days.

Joe, on 2, you get a sound that could be described as metal-like in spots—like in the dropped-D riffing in “The Outsider.” Have you always been into that genre?

Bonamassa: Yes. It might not always be obvious from listening to my other music, but I’ve long been a big fan of metal for its mystery and intrigue. It makes a lot of sense when you think about it, since metal is rooted in the blues.

How did you get that molten liquid lead sound on “Faithless”?

Bonamassa: B

with a Jim Dunlop brass slide. |

Which parts on the record are you most proud of?

Bonamassa: I really like what I did on “Save Me,” which is built around this riff that is very Zeppelin-inspired. The sound is all Marshall amp and EV speakers, and for the solo I just went for it with a bunch of sixteenth-notes that were appropriate for the urgent vibe we were going for.

Were your solos generally preplanned or improvised?

Bonamassa: They were all definitely spontaneous. That’s the way I play, to maintain a fresh sense of inspiration and to avoid sounding contrived—to keep both me and the listener from getting bored too easily.

Glenn, all of your bass lines on the record are uniformly excellent, but the one on “The Battle for Hadrian’s Wall” really stands out.

Hughes: Yes, I think that bass line is a good example of what I’m talking about when I say that the bass is an extension of my voice. Also, the song sounds a bit like the pastoral side of Led Zeppelin, doesn’t it? That’s only appropriate, being as John Bonham’s lad was in the drum chair.

You’re both in tip-top form on the record. What do you do to maintain your chops?

Bonamassa: Not a lot, to be honest. Mostly I just play two or three hours every day and that seems to do the trick.

Hughes: I play a bit every day, but more often on guitar than on bass. I’m kind of eccentric. I’ve got guitars everywhere in my house—even in the kitchen . . . vintage Les Pauls and Strats, a lovely Gibson Dove, and an old mahogany-bodied Martin. I don’t go about it in any structured way—I’ll just pick it up and play what comes naturally, whether for two minutes or two hours at a stretch, listening to the chords that come out and thinking about how I can turn them into a song. Music and songwriting really are at the center of my universe.

Hughes, Bonham, and Bonamassa in a groove. Note that Bonham’s kick drum bears the symbol used by his father, John, on Led Zeppelin IV—a rune that reportedly represents a father, mother, and child.

Joe Bonamassa’s Gearbox

Guitars

1959 Gibson Les Paul nicknamed “Magellan,” Gibson Joe Bonamassa Les Paul, Gibson Don Felder “Hotel California” EDS-1275 6/12 doubleneck, Gibson Explorer, Fender Jeff Beck Stratocaster, Music Man Steve Morse Y2D, 1969 Grammer Johnny Cash acoustic

Amps

Four Marshall Jubilee heads, four 1969 Marshall Super Lead heads, two Marshall Super Bass 4x12 cabinets with Electro-Voice EVM12L speakers, two Mojo 4x12 cabinets with Electro-Voice EVM12L speakers

Effects

Ibanez Tube Screamer, Boss DD-3 Digital Delay, Jim Dunlop JBF3 Fuzz Face, Jim Dunlop Joe Bonamassa Signature Wah

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

Ernie Ball Slinky (.011–.052 sets on both electric and acoustic guitars), signature Jim Dunlop Jazz III Joe Bonamassa picks, Jim Dunlop metal slide

Glenn Hughes’ Gearbox

Basses

Two Nash Guitars PB57s, assorted vintage Fenders

Amps

Two Laney Nexus-Tube heads

Strings

D’Addario EXL170 (.045–.100)

How did you get that molten liquid lead sound on “Faithless”?

Bonamassa: B

with a Jim Dunlop brass slide. |

Which parts on the record are you most proud of?

Bonamassa: I really like what I did on “Save Me,” which is built around this riff that is very Zeppelin-inspired. The sound is all Marshall amp and EV speakers, and for the solo I just went for it with a bunch of sixteenth-notes that were appropriate for the urgent vibe we were going for.

Were your solos generally preplanned or improvised?

Bonamassa: They were all definitely spontaneous. That’s the way I play, to maintain a fresh sense of inspiration and to avoid sounding contrived—to keep both me and the listener from getting bored too easily.

Glenn, all of your bass lines on the record are uniformly excellent, but the one on “The Battle for Hadrian’s Wall” really stands out.

Hughes: Yes, I think that bass line is a good example of what I’m talking about when I say that the bass is an extension of my voice. Also, the song sounds a bit like the pastoral side of Led Zeppelin, doesn’t it? That’s only appropriate, being as John Bonham’s lad was in the drum chair.

You’re both in tip-top form on the record. What do you do to maintain your chops?

Bonamassa: Not a lot, to be honest. Mostly I just play two or three hours every day and that seems to do the trick.

Hughes: I play a bit every day, but more often on guitar than on bass. I’m kind of eccentric. I’ve got guitars everywhere in my house—even in the kitchen . . . vintage Les Pauls and Strats, a lovely Gibson Dove, and an old mahogany-bodied Martin. I don’t go about it in any structured way—I’ll just pick it up and play what comes naturally, whether for two minutes or two hours at a stretch, listening to the chords that come out and thinking about how I can turn them into a song. Music and songwriting really are at the center of my universe.

Hughes, Bonham, and Bonamassa in a groove. Note that Bonham’s kick drum bears the symbol used by his father, John, on Led Zeppelin IV—a rune that reportedly represents a father, mother, and child.

Joe Bonamassa’s Gearbox

Guitars

1959 Gibson Les Paul nicknamed “Magellan,” Gibson Joe Bonamassa Les Paul, Gibson Don Felder “Hotel California” EDS-1275 6/12 doubleneck, Gibson Explorer, Fender Jeff Beck Stratocaster, Music Man Steve Morse Y2D, 1969 Grammer Johnny Cash acoustic

Amps

Four Marshall Jubilee heads, four 1969 Marshall Super Lead heads, two Marshall Super Bass 4x12 cabinets with Electro-Voice EVM12L speakers, two Mojo 4x12 cabinets with Electro-Voice EVM12L speakers

Effects

Ibanez Tube Screamer, Boss DD-3 Digital Delay, Jim Dunlop JBF3 Fuzz Face, Jim Dunlop Joe Bonamassa Signature Wah

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

Ernie Ball Slinky (.011–.052 sets on both electric and acoustic guitars), signature Jim Dunlop Jazz III Joe Bonamassa picks, Jim Dunlop metal slide

Glenn Hughes’ Gearbox

Basses

Two Nash Guitars PB57s, assorted vintage Fenders

Amps

Two Laney Nexus-Tube heads

Strings

D’Addario EXL170 (.045–.100)

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)