Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Intermediate

Lesson Overview:

• Learn about traditional flamenco tensions

• Add new chords to jazz tunes and rock songs

• Explore a new picking-hand technique

Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson's notation.

The sound of flamenco guitar has always attracted me, maybe because of my Spanish roots. The color of the chords used in the traditional style is something I find transporting, otherworldly, and enchanting. For a long time, those harmonies remained a mystery to me, until I heard and studied jazz and rock players who used flamenco-inspired chords in a non-traditional way. Attending a clinic by Al Di Meola some 15 years ago unlocked a lot of things. For one thing, it made me realize I didn’t need to be a traditional flamenco player to borrow some of those colors and techniques. Truly mastering flamenco guitar is a lifelong endeavor—I consider it almost an entirely different instrument—but it’s exciting to borrow sounds from very specific styles and apply them to your own music. It adds more dimensions to your playing and it makes you grow as a guitarist.

While the rhythmic aspect of flamenco is vast and fascinating, this lesson will focus mostly on the fretting hand—harmonies and chord tensions—with a little picking-hand activity thrown in for good measure.

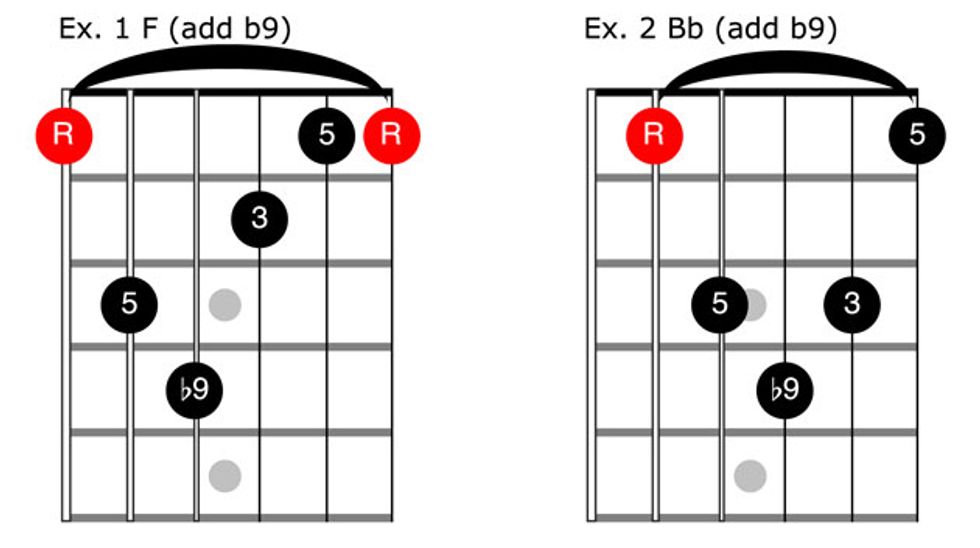

To my ears, the chord that embodies the flamenco sound best is a major chord with a b9. It can be seen as a moveable, basic barre chord with the root either on the 6th string or the 5th string. For the 6th-string version, take a basic F chord shape and raise the middle octave root up a half step (typically using your fourth finger). Move it around up and down the neck. As for the root on the 5th string, grab a Bb chord shape and raise that same middle octave root up a half-step. This will take some finger rearranging, as you’ll see in the diagrams in Ex. 1 and Ex. 2.

To understand how to use those chords and make the most of their added colors, it’s important to place them in a harmonic context. Ex. 3 is a simple progression in A minor, but with two chords that are outside the key: G and F.

Click here for Ex. 3

The next progression (Ex. 4) draws on the sound of the Phrygian scale by using a bII chord (Db) in the key of C.

Click here for Ex. 4

The maj(b9) chord that we introduced can be used as the V chord (Ex. 3), and as the I chord (Ex. 4). In Ex. 3, the V chord truly functions as a dominant chord because it resolves to the root chord. In that way, it’s similar to a jazz harmonic approach, and you can substitute this new, colorful chord for any V chord that will resolve to a I chord. Ex. 5 is an example of the traditional downward progression, implementing the maj(b9) chord.

Click here for Ex. 5

In a ii-V-I jazz context, we have Ex. 6—a colorful way to comp through this D minor progression.

Click here for Ex. 6

Ex. 7 works a little differently because the colorful, unstable chord is the root. Coincidentally, the root motion between the I and the bII can be reminiscent of a metal sort of sound, so using this new chord in that style could be interesting and fresh.

Click here for Ex. 7

Now that we have some of the shapes and sounds under our fingers and in our ears, play through Ex. 8. Watch where to mute strings and where to let them ring for maximum effect!

Click here for Ex. 8

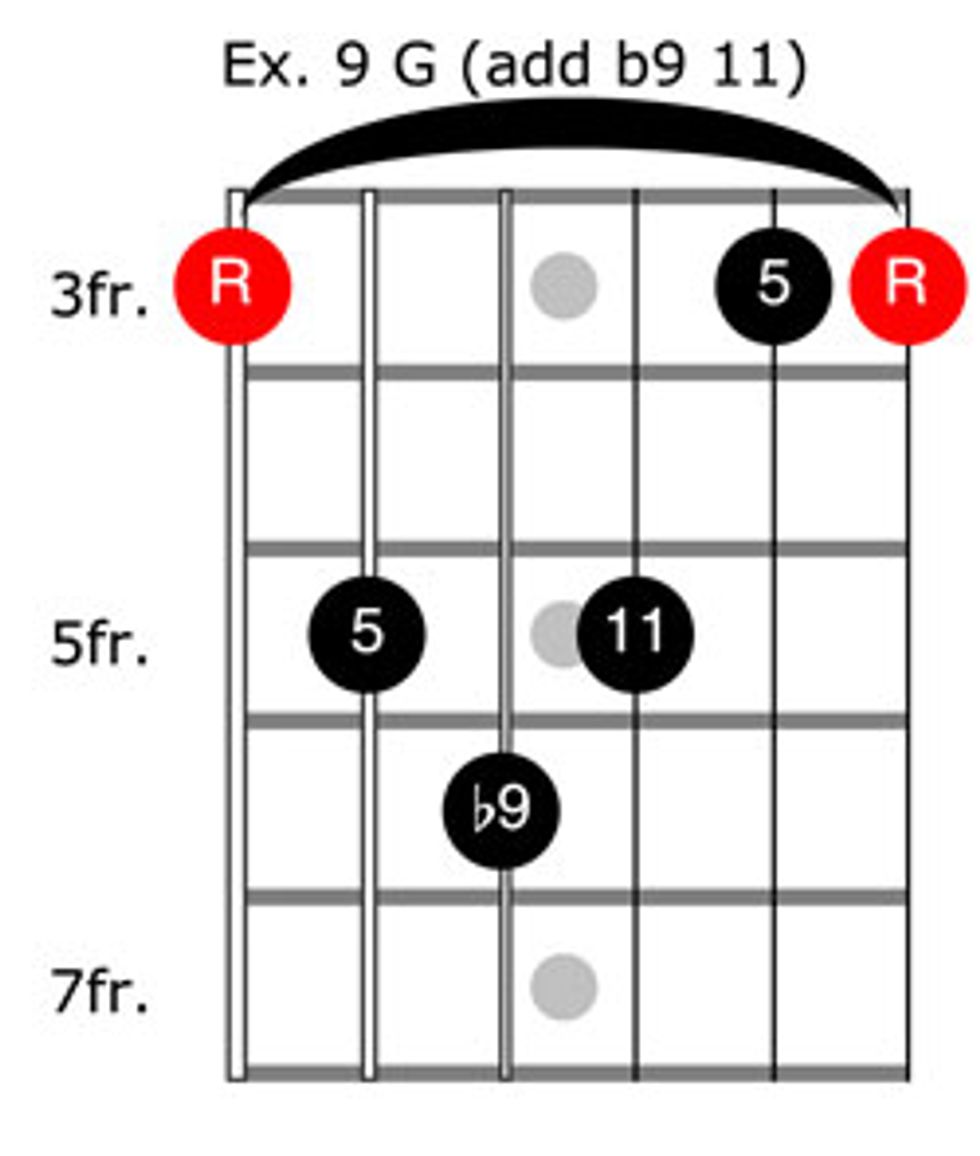

Even more tensions can be added to those maj(b9) chords. In a very guitaristic manner, the choice of tension is often dictated by the chord shape and its finger accessibility. Let’s start by taking the shape with the root on the 6th string and adding an 11 to make it very dense (Ex. 9).

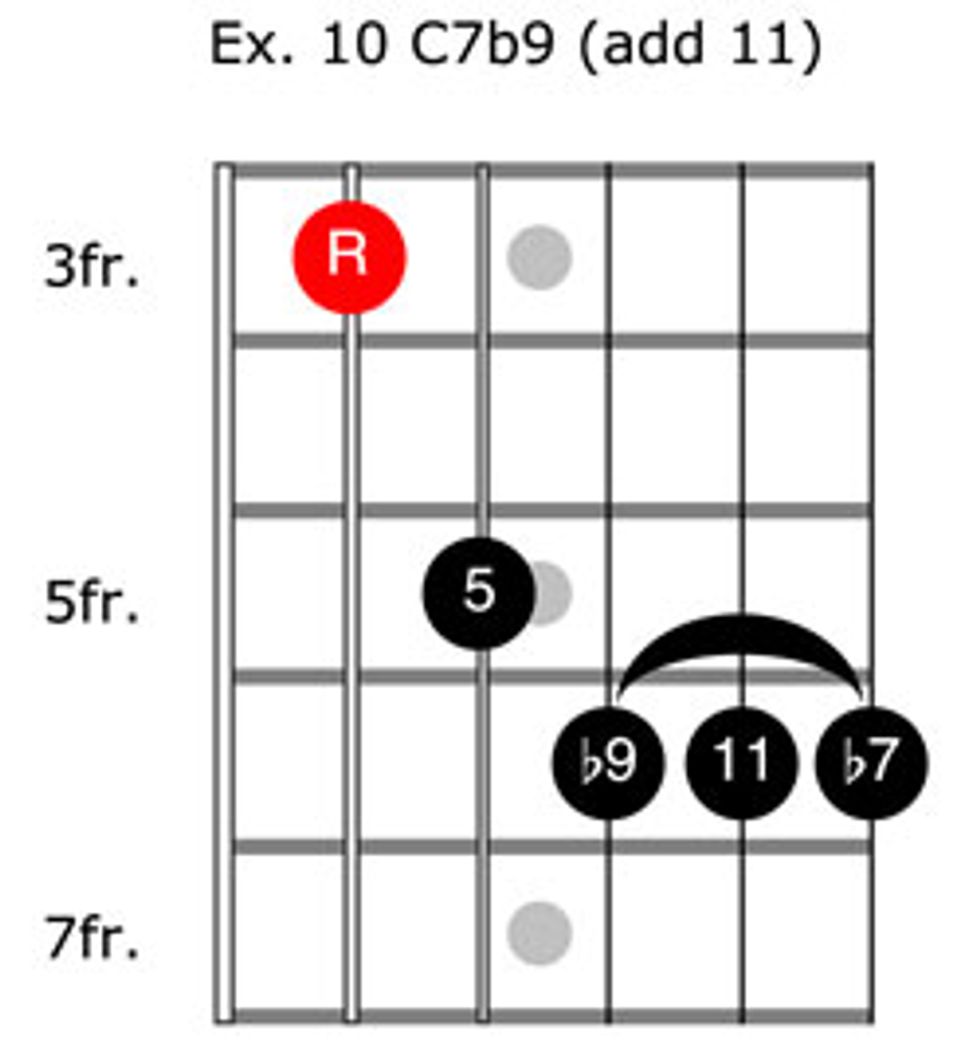

As for the 5th string shape, we can similarly add 11 to our maj(b9) chord, but we can go another level deeper and add a b7 as the top note (Ex. 10).

Using the harmonic concepts we’ve just investigated, you can mix, match, and choose the tensions you want to use on the chords. Nothing needs to be systematic or repetitive. Explore and find which sounds you like best. You can strum the chords, or play them in a more arpeggiated fashion, or a bit of both, like Ex. 11.

Click here for Ex. 11

Finally, let’s look at a picking-hand technique that emulates the traditional sound of flamenco. It’s targeted specifically to electric and acoustic guitarists who use a flatpick, so let me stress that it is far from an authentic, traditional flamenco technique, but rather an attempt to reproduce one of its sounds.

It is a very textural, non rhythm-specific sound. Your fretting hand just needs to hold down the chord. Your picking hand will quickly sweep up through the strings and back down. As the pick changes directions, you’ll need to hit both the 1st and 6th strings again. Make sure to keep the rhythm even throughout—even though it’s not a specific subdivision. Here’s a tip: Aim to hit the last bottom note on a downbeat.

Click here for Ex. 12

This is far from an exhaustive course on flamenco guitar, but I hope it will help open up your ears to new sounds and lead you to discover more of this beautiful music.