As a working musician, there’s never been a better time to be alive and wanting. There’s a near-boundless array of instruments, pickups, pedals, and amps for just about every budget, not to mention the increasingly convincing digital paths to previously out-of-reach tones now made available by modeling, profiling, and impulse-response software. In fact, as time goes on it often feels as if the lower end of the price range is where the real values are.

Some might mutter under their breath at that notion, and I get it. When I was coming up as a guitarist in the ’80s and ’90s, the more affordable models were almost universally shunned. Most players felt they simply weren’t up to snuff and were replete with tuning problems, inconsistent quality, and uninspiring tonal and visual aesthetics.

However, things have certainly changed in the modern era. Computer-aided manufacturing and other industry developments (such as boutique pickup builders developing improved designs for budget instruments) have streamlined production, broadened the types of instruments available, and greatly reduced variances in quality control. As a result, there are killer deals to be had in the sub-$500 range no matter what your taste. Whether you’re looking for your first instrument or one you can take to the pub in place of your irreplaceable 1960s custom color No. 1, there’s a guitar or bass out there that will scratch your particular itch with a price tag that’ll make your jaw drop.

But besides the killer deal that many of these models present in and of themselves, if you’re into modding—or having someone do mods for you—these more affordable designs can represent the perfect low-commitment value: For a few hundred bucks, you can often end up with a customized axe that, in many ways, is essentially on par with much pricier instruments, or you can explore unconventional new sounds on a familiar platform without having to worry about whether, say, adapting new hardware or expanding pickup cavities will devalue your high-end version. Whichever persuasion you hail from, breathe easy—you’re among friends!

For this year’s annual DIY issue, PG asked me to take a look at four of these common, low-cost models—three 6-strings and one bass purchased from an online retailer—and walk you through how I’d recommend turning them into more reliable stage and studio mainstays. (Before I get started, I want to give a big shout of thanks to Dan Michael of Rawton Customs for letting me make a mess of his workspace.)

If you’re new to modding, visit premierguitar.com/soldering101 for our comprehensive guide on soldering techniques and tips.

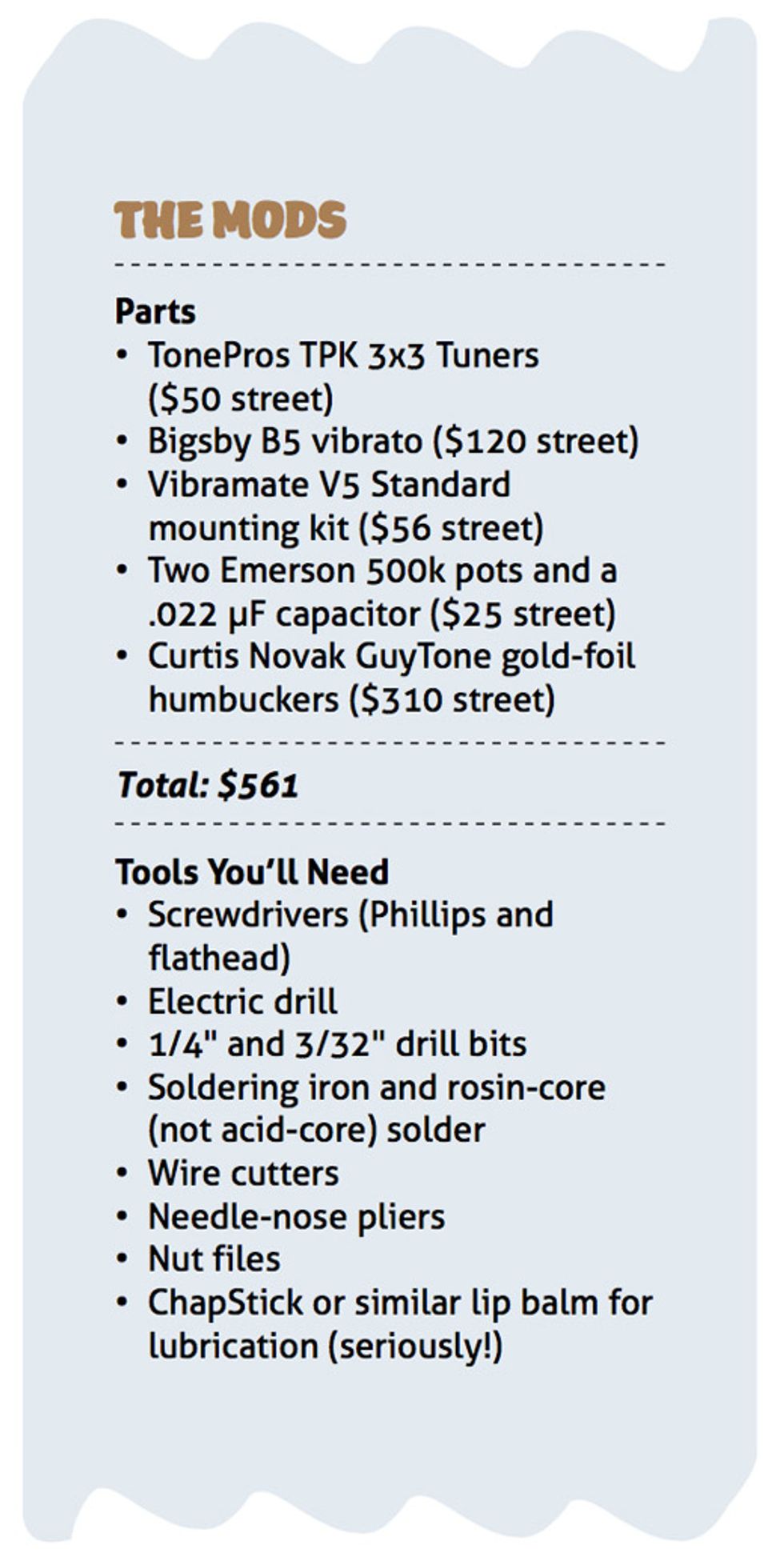

Gretsch G5426 Jet Club

$299 street, gretschguitars.com

Initial Inspection

The Jet Club comes in a flashy silver finish with enough chrome accoutrements to force a second glance. It’s an attractive instrument that begs to be played—and luckily it plays great right out of the box. Admittedly, it’s more or less a Gretsch-ified Les Paul, but it somehow fits the company’s classic aesthetic.

The G5426 has a gorgeous rosewood fretboard, and it’s fun to play thanks to the maple neck’s medium-C shape and nicely rounded shoulders. In defiance of conventional sentiment regarding bolt-on construction, it also delivers thick sustain. There’s even some midrange airiness, thanks to its chambered basswood body.

Like a lot of affordable instruments these days, the original hardware isn’t anything to write home about, but it’s also acceptably functional. The tuners turn smoothly, although to me they don’t feel super solid. Tuning stability could likely be improved by swapping them for upmarket units. In addition, I’ll look at dressing the synthetic bone nut’s slots—not because they’re particularly rough or disappointing, but just to fine-tune performance. To be honest, most guitars these days, regardless of price, could use similar attention.

Plugged in, the stock Jet Club sounded a bit dark, but that’s fairly common with entry-level imports, as lower-grade electrical components comprise a significant cost-saving measure. Even so, the Club’s stock tone is loud and surprisingly bombastic, so I’m thinking that giving some attention to the pickups and circuit will bump up the clarity factor. This one’s got some soul, and I intend to bring that out.

The only complaint I had with the Jet Club was that some of its fret ends stuck out a bit too far, resulting in prickly playing in some positions. This is something I can fix on my own without much effort—and, in defense of Gretsch’s overall attention to detail, the leveling and crowning work on the frets was flawless. I couldn’t find any notes that choked or buzzed during my initial playing tests.

All in all, this is a great guitar for the price. I’m looking forward to digging into this one—and I’m thinking we’ll go a slightly different direction with our mods, rather than try to turn this into the stereotypical “ultimate Gretsch.”

Photo 1 — A Vibramate V5 Standard kit enabled us to add a Gretsch must—a Bigsby B5 vibrato—to the Jet Club

without any drilling.

For the most part, the mods we chose for the Gretsch Jet Club couldn’t have gone more smoothly. Each bit of hardware, including the tuners, fit without any extra drilling or routing required. (The circuitry upgrades required a little extra work. More on that shortly.) The Vibramate V5 Standard kit made installing the Bigsby B5 vibrato (Photos 1 and 2) an especially painless exercise—no more difficult than turning a few screws into place! (If you’re not familiar with it, the Vibramate is a U-shaped metal platform that lets you add a Bigsby to an instrument already outfitted with a Tune-o-matic-style bridge and stop-tail without having to drill extra holes. If you can change your strings, you can install a Vibramate.)

Photo 2

Photo 3 — To ensure your new Bigsby has comfy, squishy action right out of the gate, place the spring on the floor and put all your weight on it 30–45 times.

One thing I like to do with new Bigsby vibratos is eliminate the break-in period for the spring—which can otherwise yield rather stiff arm action for quite some time. In the spirit of generosity, I pass this trick onto you: Place the spring on the ground and step on it 30–45 times (Photo 3). I’m telling you, it works! Oh, and one more tip—toss the nylon washer that’s supposed to go under the spring in the trash, and use a penny instead. It’ll last longer and yield to pressure less.

The only Gretsch alterations that required some slightly more significant alterations were the potentiometer holes. I had to gently enlarge the existing holes to accommodate the new Emerson parts. This is a common distinction between most U.S.-made instruments and those made overseas—in fact, we encountered it with every instrument modded for this article.

Photo 4 — As with most import electrics, the G5426’s potentiometer holes are a bit narrow to fit higher-end Emerson pots. I used a 1/4" drill bit—operating in reverse—to very carefully widen the holes and minimize the likelihood

of unsightly wood tears.

With the Gretsch, making the pots fit required a 1/4" drill bit and a technique called reverse drilling that’s as self-explanatory as it sounds––you’re literally drilling in reverse: When the drill turns counterclockwise, it eliminates the chance that the bit will grab the wood and tear it out, which comes in handy when you need to get rid of a little wood in an area that may be partially visible. After only a moment, the new pots fit right in place (Photos 4 and 5).

Photo 5

For the wiring tweaks in all four of these instrument-modding projects, I prewired harnesses to make quick work of pickup installation—in this case, Curtis Novak’s brand-new Guytone gold-foil humbuckers. I’m really excited to try out these pickups, which are based on the old Guyatone pickups but in dual-coil format.

Photo 6 — The Jet Club’s original pickup rings had holes for three (rather than the standard two) height screws. To accommodate the new pickups’ two-screw setup, I drilled a new hole in the center of the two-hole side of each ring, then rotated the rings around so the unused holes would be obscured by the pickguard.

The one problem I ran into with the pickups should have been obvious from the start, had I been paying closer attention: The Jet Club’s original chrome mounting rings have three holes for pickup-height screws, not the standard two. Remedying the problem wasn’t too tough, though: I simply used a 3/32" drill bit to drill a new hole in the center of the side of the pickup ring that had two holes, then rotated the rings so that the side with the two unused original holes was hidden under the pickguard (Photos 6 and 7). Problem solved!

Photo 7

Once everything was in place, I restrung the guitar and put in some extra maintenance that often gets overlooked on trem-equipped instruments. Often the reason vibrato units get a bad rap isn’t because of any shortcoming with the whammy itself: It’s due to a poorly cut nut, bad stringing techniques, and bridge saddles that weren’t intended to have strings grinding away at their rough edges. A little filing of the nut and saddle slots, some lubrication in key areas, and the Gretsch G5426 Jet Club was good to go.

Post-Mod Thoughts

The guitar we started with was pretty good, but the one we ended up with had far greater depth and dimensionality to its tones and playing flexibility. Dressing the nut and fret ends made worlds of difference for playability, and the Curtis Novak pickups are fantastically dynamic—every bit as vocal as any good gold-foil I’ve heard, but far quieter. The guitar now has a bright midrange character that just sings. It’s equally at home with clean tones and gritty fuzz. Honestly, this Gretsch may be the biggest surprise of the group!

Squier Vintage Modified Jaguar

$399 street, squierguitars.com

Initial Inspection

As has been my experience with the whole of Squier’s Vintage Modified line, the Jaguar offers serious bang for the buck. I really can’t say enough about the consistency of this series. I’ve owned and worked on several, and overall I’ve been really impressed with the fundamental aspects—the neck shapes, the average weight, and the fit and finish—of each.

The one thing I’ll concede often isn’t great on floor (or online-purchased) models of Leo Fender’s unique Jaguar design (as well as the similarly equipped Jazzmaster) is the setup. This holds true for the Squier VM we’ve got here. Straight out of the box, all the familiar complaints you hear about “offset” guitars (a nickname for instruments with asymmetrical inner body curves like those on the Jag and Jazzmaster) were realized, from loose, rattling bridge saddles to poor tuning stability. This is because Jazzmaster/Jaguar hardware and construction peculiarities are often misunderstood by the average player and shop setup person. Optimizing Jaguar and Jazzmaster performance requires specialized knowledge that can seem foreign to players used to Stratocaster-, Telecaster-, or Les Paul-style instruments. Thankfully, the retailer’s setup oversights and shortcomings can be corrected by following the Jazzmaster/Jaguar setup techniques I outlined in PG’s May 2017 issue.

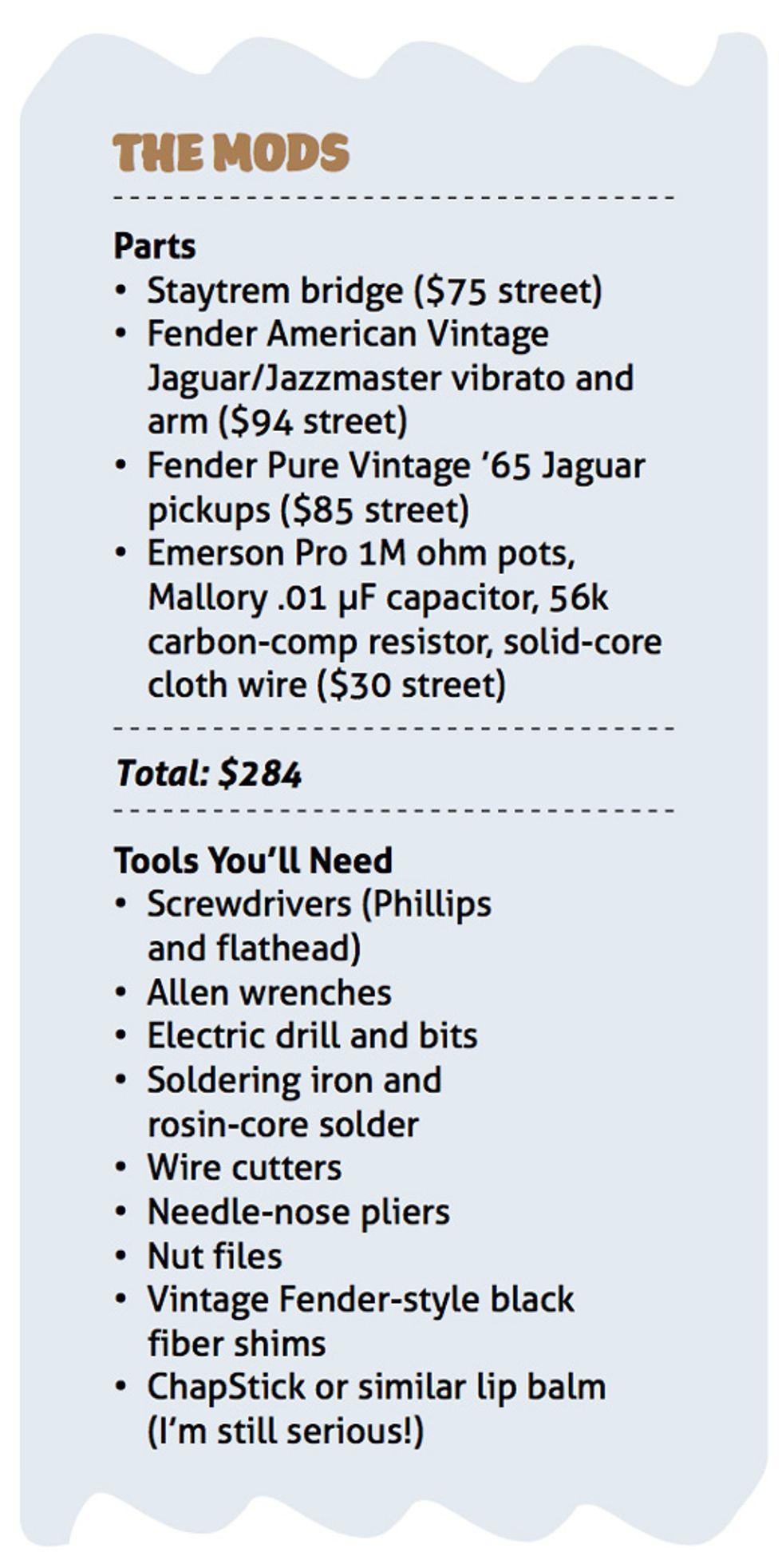

I’ll be focusing on two major areas in our Jag mods: electronics and hardware. We’ll be upgrading the bridge, vibrato, pickups, and lead-circuit electronics, but we’ll leave the less-used rhythm circuit (the panel on the upper, bass-side bout of the guitar) alone. There’s no reason to change out the tuners, as they’re sturdy and reliable as-is.

If you’re enough of a Jaguar or Jazzmaster nerd to have tried installing a U.S.-made Jag/JM vibrato on Fender’s Japanese-made versions of either model, you very likely had to do some extra routing to make it fit. Luckily that’s not the case with these Indonesian-made Squiers. I suspect they’re using U.S. templates, because the American Vintage reissue vibrato fits perfectly without any extra finagling. Even Fender American Vintage pickguards line up, just in case you feel like adding a more minty or parchment-y vibe to your Jag. I’m just in awe of how right they got all this!

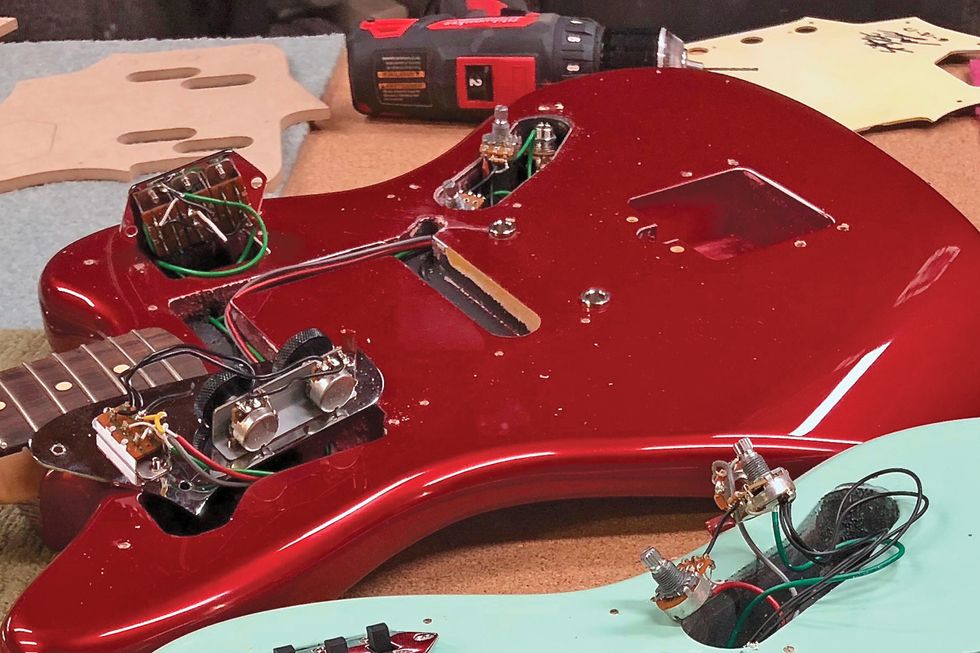

Photo 8 — Squier’s Vintage Modified Jaguar is a modder’s dream—the factory routes and screw holes allow easy, drop-in replacement of the most common components that offset fans like to upgrade.

Another bit of good news: The Jag’s control-cavity routes were more than ample to fit full-size U.S.-made potentiometers. That said, the pot holes in the lead-circuit body plate (the control section nearest to the vibrato) did need to be drilled out in order to go from mini pots to the larger shafts in full-size ones. As for the switches, I often recommend upgrading them, but these ones felt solid enough.

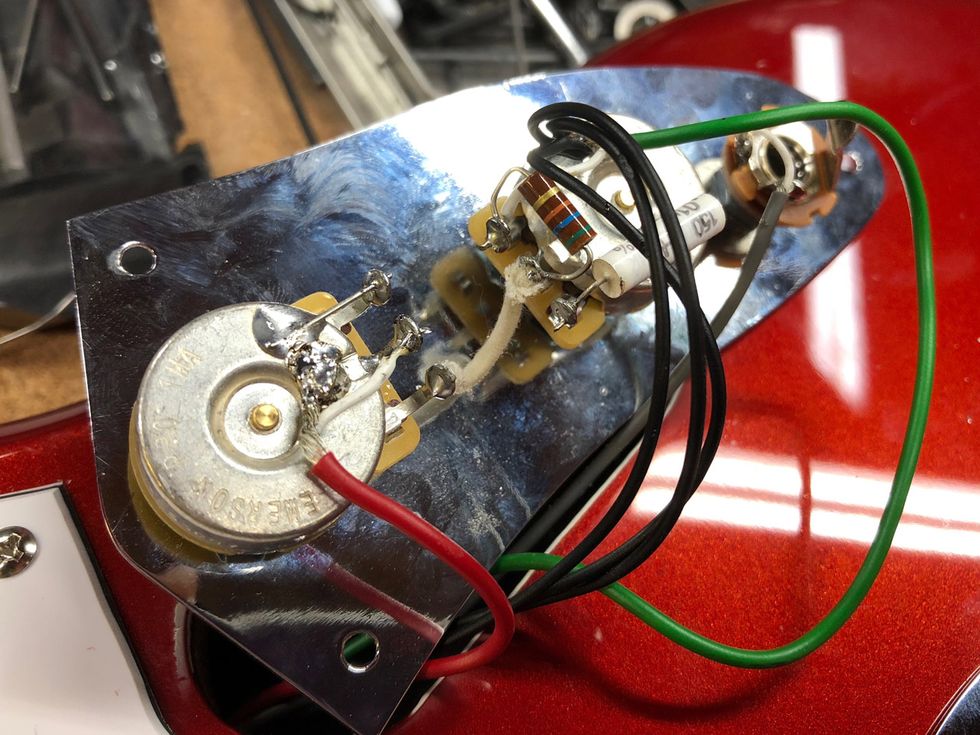

Photo 9 — The Jag’s lead-circuit control panel after widening the pot holes and installing U.S.-made 1M potentiometers and a Mallory .01 μF capacitor on the tone pot.

Instead of completely rewiring the guitar, I built a harness for the lead circuit (the two treble-side panels, one of which houses three sliders, and the other of which has standard-sized volume and tone knobs) using solid-core, vintage-style cloth wire, Emerson 1M pots, a Mallory .01 µF capacitor, and a 56k carbon-comp resistor for the “strangle” function (a bass-reduction function engaged by the treble-side slider closest to the bridge pickup). I paired the wired-up harness (Photo 9) with Fender’s fantastic Pure Vintage ’65 Jaguar pickups, which are nice and deep on the low end, and bright but not tinny on the highs.

As I mentioned before, we’ve tossed the VM’s original vibrato in favor of a Fender American Vintage unit, which offers a serious upgrade in performance, thanks to more consistent manufacturing. While I have a personal preference for the playing response of actual vintage Fender Jag/JM vibratos, as well as Mastery Bridge’s JM-style vibratos, I’ve happily installed these American Vintage units for many a budget-minded musician without reservation.

Photo 10 — With the new U.K.-made Staytrem bridge and Fender American Vintage vibrato installed, the Squier is starting to look more and more like an offset obsessive’s dream.

To remedy the Jaguar’s usual loose/buzzy/unstable saddle situation, I’ve installed a Staytrem—a popular upgrade for offset obsessives (Photo 10). Made in the U.K. out of solid stainless steel, the Staytrem is a more robust Mustang-style bridge that aims to retain the feel and sound of Leo Fender’s original Jag/JM design while also featuring deep grooves in its fixed-radius saddles to prevent strings from slipping out of place under aggressive attack—a common Jag/JM problem.

Once the new hardware was in place, I restrung the Jag with .011–.048 strings, since many enthusiasts find heavier strings to be a better option for the guitar’s shorter 24" scale. I also took some time to appropriately shim the neck to assure adequate clearance and comfortable playing action with the new bridge (see the aforementioned Jazzmaster/Jaguar setup piece for more detail on this).

Photo 11 — Because we’ve increased the Jag’s string gauge from the stock .009 set to an .011 set, filing the nut slots to match the new set’s gauge is imperative for both comfortable action and tuning stability.

Because Jaguars come from the factory with .009-gauge strings, it’s imperative that the nut slots be dressed to match the thicker gauge. Nut slots that are too small or poorly cut will grip the string, causing tuning problems—especially on a vibrato-equipped instrument. You can easily widen nut slots yourself, provided you have access to a decent set of files. I’ve been using the same Stew Mac files for years, but any gauged file with a rounded bottom will do just fine (Photo 11). After opening up the nut, the strings glide smoothly and stay in tune perfectly.

Note: When filing nut slots, remember to keep the file angled slightly down toward the headstock, so the highest point of the slot remains on the edge of the nut that’s closest to the fretboard. To avoid “sitar buzz,” the slot must guide the string down toward the string post.

Post-Mod Thoughts

When all was said and done, I was blown away by how the Squier Vintage Modified Jaguar came alive. Besides having all the usual offset kinks worked out, it’s got newfound brightness and depth on tap, as well as a wiry, tough, taut feel availed by heavier strings that are more reliably channeled and anchored by the Staytrem bridge and smoother-performing vibrato. I’d gladly take it onstage with me—that I can say for sure.

Squier Vintage Modified Precision Bass PJ

$299 street, squierguitars.com

Initial Inspection

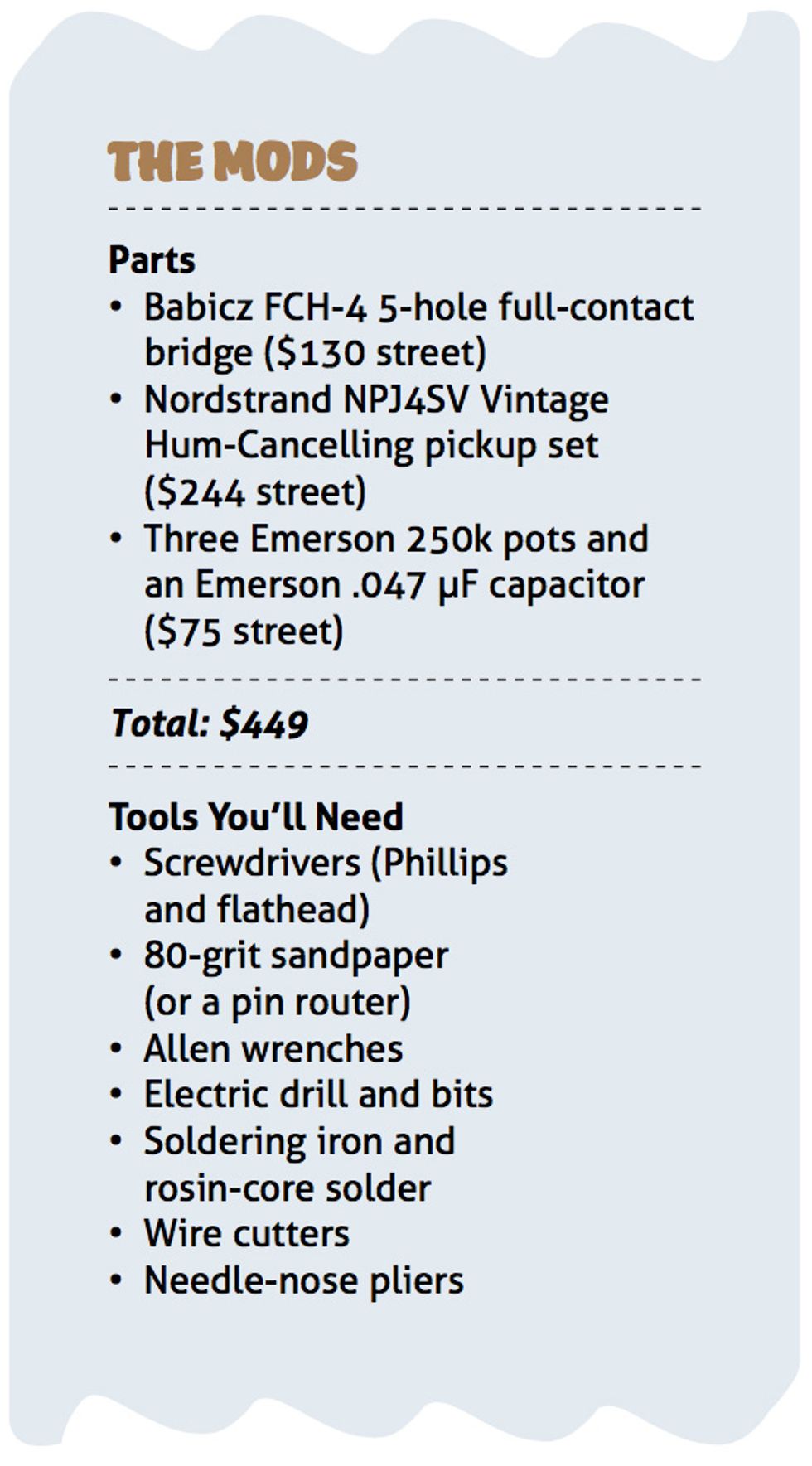

As the only bass we’ll be working with in this DIY round, this Squier Vintage Modified Precision PJ has a lot of pressure on it to bring home the bacon. Thankfully, the $299 instrument is actually quite good.

I’d have no problem recommending it to anyone in need of an affordable backup or a replaceable touring instrument. I love the color and the weight, and I was even rather impressed with the sound of the stock electronics. It plays pretty great, too. Honestly, if there weren’t a whole to-do about mods for this issue, I’d probably just leave it be. But where’s the fun in that?

The mods for the PJ were all pretty straightforward. The Babicz bridge is hugely popular with bass wizzes because its hefty aluminum construction and double-locking saddles tend to improve both sustain and intonation. But it’s also a hit because it uses the same five-screw pattern as the original Fender Jazz and Precision bass bridges, making it a no-brainer swap because it doesn’t require any extra filling or drilling of holes.

The only area where I hit a snag was fitting the new full-size tone pot at the lower tip of the pickguard. Standard Precision basses have two knobs—a volume and a tone—with a pickguard-mounted output. But since our Squier Precision PJ has two volumes and its tone knob is located where the P’s jack would normally be, the PJ’s output jack is mounted on the side. Unfortunately, the jack also isn’t far from the tone control, which means its inner portion comes quite close to the tone pot.

Photo 12 — Before using a pin router to slightly expand the PJ’s control cavity to accommodate a larger, higher-quality tone pot,I marked the pickguard outline and the area that needed to be trimmed with a marker and masking tape.

On the bright side, using a pin router (80-grit sandpaper and a little elbow grease will work, too), I was able to remove enough wood from the cavity (Photo 12) to fit the upgraded tone pot. Even so, there wasn’t enough room to fit the sweet—but also very large—.047 µF Emerson capacitor (Photo 13). I had to substitute a thin metal-film capacitor instead.

Photo 13 — Although expanding the control allowed the tone pot to t, the output jack was too close to accommodate the hefty Emerson capacitor. I had to swap it with a metal-film cap.

From there, things got easy again. The upscale Nordstrand pickups fit perfectly and wired up incident-free—though I was thankful for the “Where Does the Small Gray Wire Go?” info sheet, as I was in the process of asking that very question the moment I saw the wire. That’s some thoughtful customer service, right there!

Post-Mod Thoughts

For its price range, the Squier Vintage Modified Precision PJ was already an impressive bass, but after these mods it became something quite different. It’s louder, more authoritative, and sounds positively enormous. Sure, it still has that vintage Fender bass midrange with the P pickup soloed, but the Nordstrand pickups excel when used in tandem. The bass now straddles vintage and modern sounds with ease, and it’s also dead quiet no matter which pickup you favor. It loves fuzz, too!

Epiphone Les Paul SL

$99 street, epiphone.com

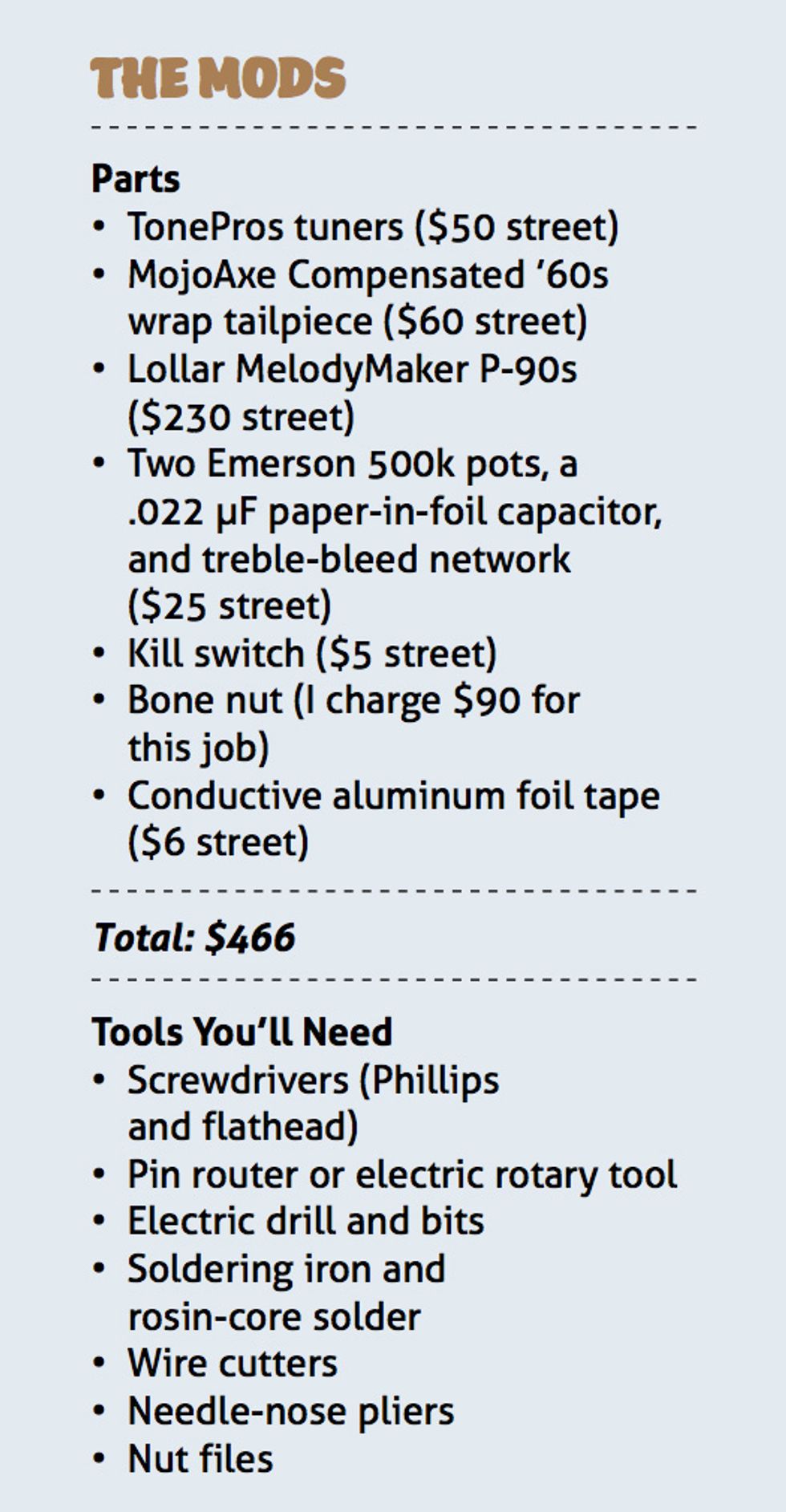

I remember when Epiphone announced this model at NAMM last year. The moment I heard the ridiculous price I wanted one—even though I damn well didn’t need another guitar for literally any reason. The pickguard lines echo ’60s Gibson Melody Makers, and the colors—which range from the black we chose here to a couple of bursts and a few candy-like pastels—just drew me in. Somehow, though, I didn’t get a chance to play one until our project guitar arrived on my doorstep.

Initial Inspection

At the paltry sum of $99, the Epiphone Les Paul SL is far and away the least expensive guitar of our group, and it wears that price point on its sleeve. It’s rudimentary and uncomplicated, neither refined nor streamlined. And, to be honest, playing an unmodified specimen can conjure conflicting feelings: At times it’s pleasant and enjoyable … at others it’s uninspiring, even a little confusing.

But who are we kidding here? No reasonable person would expect a flaw-free experience at this price point, so minor finish issues and thin-sounding pickups shouldn’t surprise us. Given its dimensions and pedigree, it’s no surprise that the poplar-bodied instrument is light, but to some it might even feel unsettlingly so. The mere presence of tuners seems to throw off its balance when worn on a strap, and in some ways the SL makes one wonder whether, long-term, it will handle the rigors of guitar life.

Considering all that, the question became: Can the SL be elevated by a few thoughtful alterations? I firmly believe any guitar can be made to play and sound better, so from this point on I’ll be treating the Epi the same way Ed McMahon treated daytime TV viewers in the 1980s: Little friend, you may already be a winner.

I’ll be swapping out the nut, electronics, pickups, pickguard, and hardware. And, since the fret ends were jagged enough to do some minor skin damage while unboxing the guitar—not to worry, I didn’t bleed on it—I put fretwork on the mod list as well.

Photo 14 — To improve the Les Paul SL’s tuning stability, I used a drill press to carefully widen the existing tuner holes to accommodate a set of smoother-operating TonePros machines.

As we’ve discussed, lower-quality electrical components are one way manufacturers often cut costs on more affordable instruments. On a guitar as inexpensive as the Epi SL, hardware is definitely going to come into that picture, too. It was soon apparent that its tuners just aren’t worth salvaging, so I installed a set of white-button TonePros for a visual and functional upgrade. Because these tuners have a stabilizing lip surrounding the tuner shaft, I had to remove some material around the existing (unevenly drilled) tuner holes to make room. We used a drill press for a clean look, but you can get away with some careful reverse drilling (Photo 14).

As previously hinted at, fretwork was the SL’s Achilles’ heel. Notes were choked off in some playing positions, especially at the second fret. Using a Stew Mac Fret Rocker, I was able to pinpoint a number of frets that weren’t seated properly. Pressing them back into their slots with an arbor was the only option—not exactly a job for a first-time modder, but nevertheless it was essential for our guitar. During this process, I was rather surprised to note that the neck wood (which is listed as being mahogany on the company’s website) was soft enough that slight to moderate pressure left a small depression in it.

Photo 15 — The underside of the Les Paul SL’s pickguard, prior to removing the stock pickups and electronics.

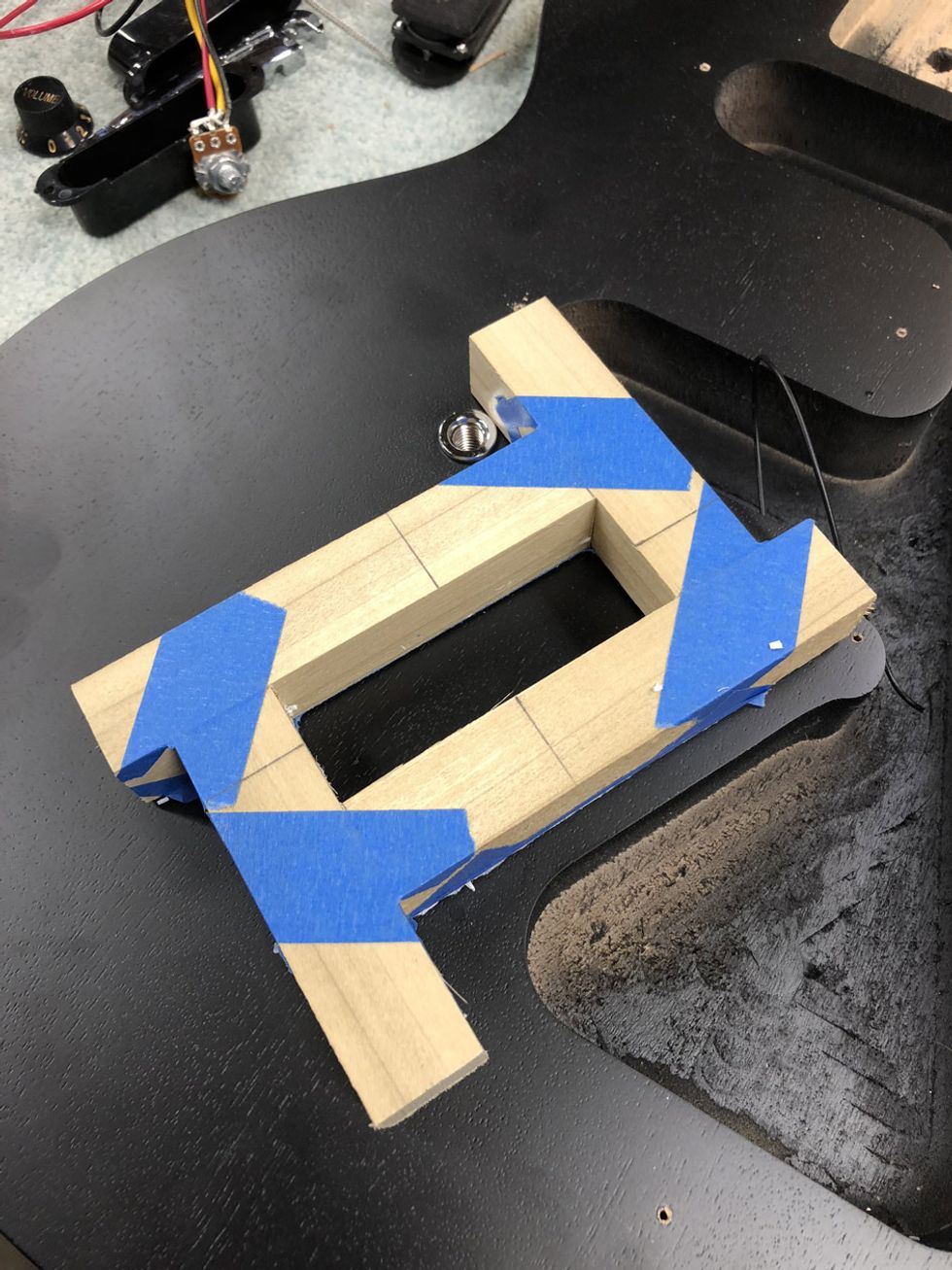

Perhaps the most valuable upgrade––literally and figuratively––was the pickups. The stock single-coils sounded thin and lacked punch, so I chose pickups from the opposite end of the spectrum: Lollar MelodyMaker P-90s. The SL’s pickguard had to be tailored to fit them—a job that can be done easily with a rotary tool like a Dremel—but I used a pin router and a makeshift jig that my friend Dan whipped up from scrap wood and tape (Photos 15 and 16).

Photo 16 — To expand the pickup routes in the SL’s pickguard to accommodate our new Lollar MelodyMakers, I used a pin router and a jig we made out of scrap wood and tape.

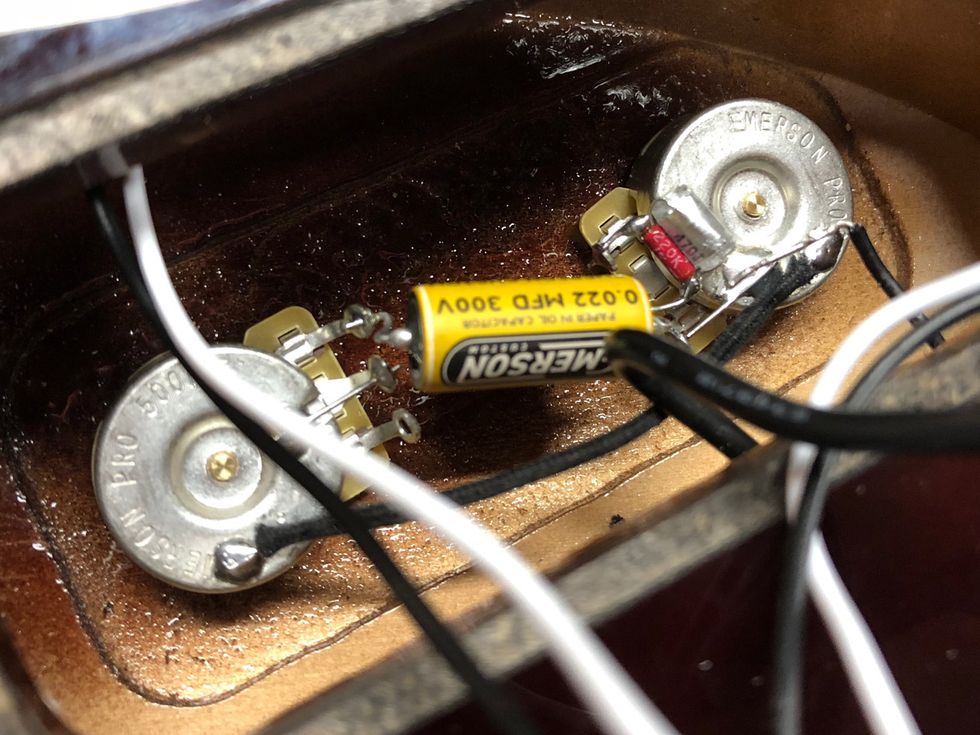

For the new wiring harness, I opted for a ’50s-style Gibson approach: two 500k pots, a .022 µF capacitor, and one of Emerson’s lovely treble-bleed networks to preserve high end with volume roll-off.

As a bonus, I threw in a spare kill switch that my tech friend Ed Dualetta gifted me years ago, which I thought might be fun. It’s wired between the volume pot and output jack, and sends the signal to ground when the button is pressed.

Photo 17 — Although our replacement MojoAxe tailpiece fit on the SL’s existing posts, there was a gap that could cause unwanted rocking with the bridge.

The MojoAxe bridge slid right on, although the stock bridge posts left some extra wiggle room (Photo 17).

Photo 18 — A quick, easy way to rectify the rocking situation is to nab a couple of leftover pot washers, clip out a small section from each, then slide one into place on each bridge post.

One of my favorite, cheap fixes for this is to use the leftover washers that come with pots as fillers under each side of the bridge to keep it from rocking (Photos 18 and 19).

Photo 19

Use a pair of wire clippers to turn them into a C shape, push them onto the post, and—voilà!—you’ve got a tight fit (Photo 20).

Photo 20 — The clipped washers make our new compensated bridge fit snugly on the posts.

I went the extra mile and cut a fresh bone nut to replace the Epi’s original plastic one. I just couldn’t help myself! My only regret here is that I absentmindedly copied the slim string spacing of the original—I wish I’d spread it out a pinch. Ah, hindsight. For those inclined to dip their toes into the nut-making process, StewMac.com has some great resources for starters.

Photo 21 — To improve the Les Paul SL’s tuning stability, performance, and tone, I fashioned a new nut out of bone.

No tricked-out guitar would be complete without some thoughtfully applied shielding—your first, best defense against the sorts of unwanted noise that are more common with single-coil pickups like our new Lollars.

Photo 22 — Aluminum-foil tape in the interior cavities helps decrease extraneous noise. Before removing the tape’s backing, I unroll a length of tape to estimate how much is needed, then press my finger along the cavity edge to create a line I can follow when cutting the tape. Applying tailored pieces of foil is then much easier.

As long as it’s done right, it’s super effective. I used a roll of conductive aluminum-foil tape that I picked up at the hardware store for a scant $6. Rather than address the copper vs. aluminum debate here, I’ll simply agree that, yes, copper is the better insulator, but I’ve never found it to be so much better as to justify the added expense. No matter which material you prefer, the most crucial part of shielding is that it must be comprehensive—that no interior surface is left unlined. Continuity is also vitally important, so it’s best to use bigger pieces of tape instead of many small, overlapping bits.

Photo 23

To start, I’ll estimate the length of tape I’ll need, cut it, then gently trace the shape of the cavity with my finger to create an outline that I can cut out with a razor blade on a separate surface. Once the shape’s sorted, laying it down in the channel is a snap.

Photo 24 — Notice that little strip of foil at the far right end of the body cavity? (It looks like blue tape because of reflections from the blue wall.) That ensures that the cavity shielding connects with the pickguard shielding to create a complete barrier against unwanted noise.

For the cavity walls, I use the longest piece of tape possible and affix it vertically around the perimeter with some overlap where it meets the other pieces. Be sure to leave a small overhang onto the body to make contact with the pickguard, which I’ve already lined with foil and trimmed to fit. Boom—Faraday cage!

Post-Mod Thoughts

So, was all of that work on the crazy-affordable Epiphone Les Paul SL worth it? For sure! Thanks to the new components and fine-tuning touches, it’s a much more robust instrument but still retains its delightfully scrappy character. Especially with those Lollars, this could be the knock-around stage brawler of a post-punk rocker’s dreams. It can do subtle, don’t get me wrong, but it seems happier when it’s cranked up and thrown around.

Why Not Just Buy Better Instruments?

For a lot of players—especially those who aren’t particularly fond of projects—the most “obvious” question with all of this is, “Why not just save up a little and buy a better guitar (or bass)?” And sure, that’s valid for some people. For others, finances are simply too tight to get the combination of classic aesthetics, features, and tones they want in a higher-end instrument. Not to mention, the worth of a guitar can’t be strictly quantified in dollars and cents. Sure, you can throw down a few hundred more from the start and get a fine player, but being a musician and a tinkerer seem to go hand-in-hand. Never mind the fact that lots of us spend thousands more than we did here and still find ourselves wanting new pickups and swapping components. And, in all honesty, I’ve played instruments costing as much as four times what we spent on any one of these guitars, and I still felt like they needed many of the same mods we did for these instruments.

Just as importantly, at least for a lot of us, modifying these guitars was fun. To me, that’s priceless. Buy a cheap guitar, open it up, make some changes, and learn something along the way. Maybe you’ll find that you’re more self-sufficient on the other side.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig