Given the DIY nature of this issue, we thought it would be appropriate to address good soldering technique. If you’re willing to invest a few bucks in some modest tools and spend a little time practicing the basics, you can learn to wire up guitars, stomp kits, speaker cabinets, and even do some simple amp mods. Once you understand the fundamentals, you can save money and derive a lot of satisfaction from working on your own gear.

The tools.

You’ll want a decent soldering pencil (a small type of soldering iron) rated at least 25 watts, but no more than 60 watts. (Many guitar techs like a 30-watt soldering iron for working on guitars and amps, and a 15-watt iron for working inside stompboxes and on delicate printed circuit boards.) You’ll also want a stand to hold the hot iron when not in use, a damp sponge, and some rosin core solder made for electronic work (Photo 1).

Photo 2 — If your soldering stand doesn’t house a sponge, just put a damp household sponge in a glass or ceramic dish. Other helpful tools: a hemostat and small clamps to hold parts still as you solder them, and a “solder sucker” bulb for removing solder.

You should also have some basic hand tools, such as wire strippers, needle-nose pliers, wire cutters, and something to hold the wire in place while a solder joint cools (Photos 2 and 3).

Photo 3 — In addition to hook-up wire, you’ll want wire strippers. Alternatively, luthier suppliers offer old-school “push-back” wire with a waxed cotton jacket (center) that eliminates the need for stripping off the plastic insulation from the end of the wire. Electrical tape and heat shrink tubing come in handy when you need to protect or insulate your work.

There are tools sold specifically for holding wires and parts, available through an electronics supply house.

Step 1: Prepare the Joint

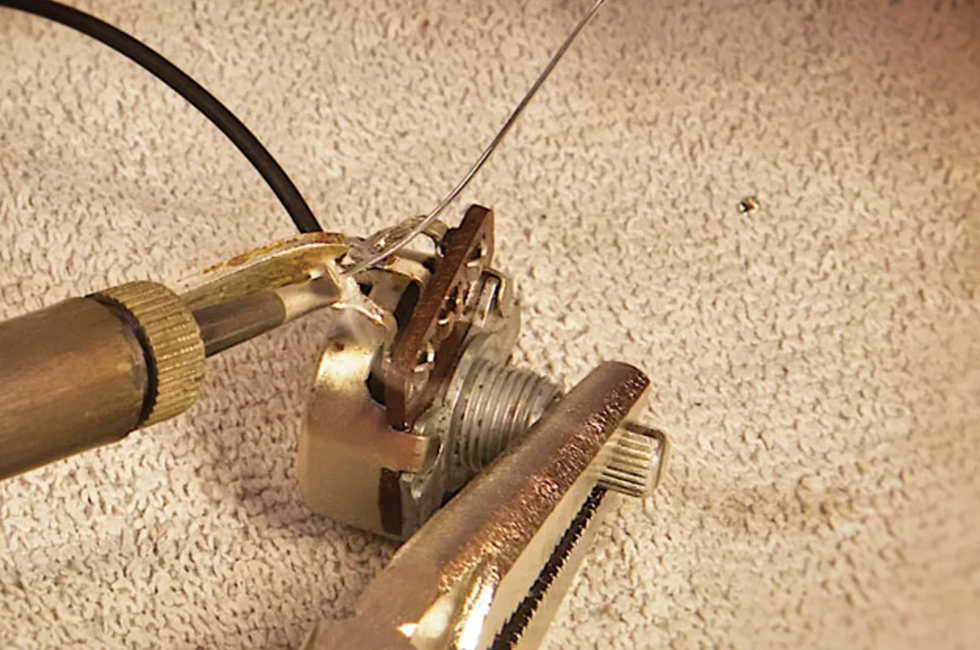

Photo 4 — Before you attempt to solder a connection, the wire and component must be secured to assure they remain absolutely motionless. Here, a spring-loaded heat-sink clamp holds the wire in place while a vice grip gently clamps the pot shaft.

For every joint, you need to find a way to hold the wire in position without using your hands (Photo 4). Wrap the wire through the solder lug once to make it hold tightly on its own, use tape to hold it in place, lay a pair of pliers on the wire to hold it firmly where you want it, or use a mechanical soldering aid to hold it. Use whatever works, except holding the wire manually. When you make a solder connection and rely on your hands to hold the soldered wire steady while the joint cools, you will fail—no human hands are steady enough to hold anything perfectly still, and you want the wire to remain absolutely motionless while it cools. If there is movement, the result will be internal fractures in the solder.

Step 2: Clean the Tip

Photo 5 — Wipe the hot tip with a damp sponge to keep it clean.

The tip must be cleaned before each and every joint—you can use the damp sponge for this (Photos 5 and 6).

Photo 6 — A clean, dross-free tip looks smooth and shiny.

Solder produces a by-product called dross very, very quickly, and the dross fouls the tip, preventing good heat conduction and introducing waste material into your solder joints.

Step 3: Tin the Tip

Photo 7 — Add a small amount of solder to a freshly cleaned tip just before you solder a connection. When you see this telltale puff of smoke, pull the strand of solder off the tip, shake off any excess, and then move quickly to the joint.

Immediately before you get on the joint with the heat, add fresh solder to the tip of the iron to “tin” it. Simply feed solder directly onto the tip so it’s completely coated (Photo 7). A tinned tip will provide much better heat conduction than a tip that’s clean but not tinned.

Step 4: Remove the Excess Solder

Shake off the excess solder after tinning—you want the tip coated, but not dripping. I have a fire-resistant container beside my soldering bench, and after tinning I tap the barrel of my iron on the edge of the container to knock excess molten solder into it. You can use any fire-resistant container for this, such as a tin can or ceramic bowl, but use care not to start a fire. Because solder melts at such a low temperature the risk of a fire is very low—molten solder is unlikely to ignite even highly flammable materials like paper—but use care anyway!

Step 5: Get on the Joint Right Away

As soon as you’ve removed the excess solder from the tip, get right on the joint. By “joint,” I mean the wire and the solder lug, or the wire and the back of the pot, or whatever it is you’re soldering. Dross will start to form on the tip very quickly, so as soon as the tip is prepared, get to work.

Step 6: Heat the Joint

Photo 8 — Gently press the iron’s hot tip against the joint to heat it before you bring the solder into the equation. The goal is to make the joint itself hot enough to melt the solder.

Heat the joint, not the solder (Photo 8). You want the joint to be hot enough to melt the solder. It’s a given that the iron is hot enough to melt it—just feed a little onto the tip and you’ll see—but you also want the joint itself to be hot enough to do the same.

Photo 9 — While holding the tip against the joint, feed the solder onto the heated joint, not the soldering iron tip. Here the emerging puff of smoke indicates the solder is melting.

If you feed solder onto the joint without it touching the iron (Photo 9), the solder will melt and be attracted right to the joint. You can watch the solder actually wick out onto the surface you’re soldering to—this is what you want.

Step 7: Get off the Joint

As soon as the solder has flowed onto the joint properly, remove the heat from the joint. Most components can stand a fair amount of heat, but some are more susceptible to damage than others, so there’s no need to push your luck. Pots are fairly durable (unless it’s a cheap pot), so it’s highly unlikely you’ll damage one by trying to solder a wire to its back. But again, there’s no need to push your luck, so as soon as you’ve completed the joint, pull the iron away and let the joint cool with the components remaining motionless.

Photo 10 — When the molten solder has flowed into the joint, pull away both the solder and iron. Keep the joint motionless as it cools and don’t blow on it—the moisture in your breath will enter the cooling connection and potentially cause it to fail.

If you’re soldering to a ring-shaped solder lug, then you’ll want to fill it completely with solder (Photo 10). This will maximize the mechanical strength of the joint.

Like most skills, soldering proficiency is acquired through practice. Employing good technique will allow you to become competent all the more quickly, so follow these steps, and you’ll be soldering like a pro in no time. You should probably practice on projects that aren’t expensive or mission critical—you might want to think twice about rewiring your only guitar before that gig with Clapton tonight. But if you keep at it, you’ll be one step closer to being a consummate DIY’er.

Two Ways to Improve Your Soldering Projects

After you master the basics, there are two more skills to add to your bag of tricks: removing old solder and installing heat shrink tubing. There are plenty of occasions where you’ll wish you could remove old solder and re-use a part. For example, you might have rescued a volume or tone pot from a previous mod or project. If it’s a high-quality pot, like those from CTS, why toss it and buy a new replacement when you can put the old one back into service? It’s easy to reverse the soldering process and remove old solder and bits of wire. You simply need a solder removal tool. There are several types, including disposable braided wire that’s designed to wick molten solder away from a joint, and various vacuum pump tools and “solder suckers.” I prefer a simple rubber bulb with a heat-resistant Teflon tip.

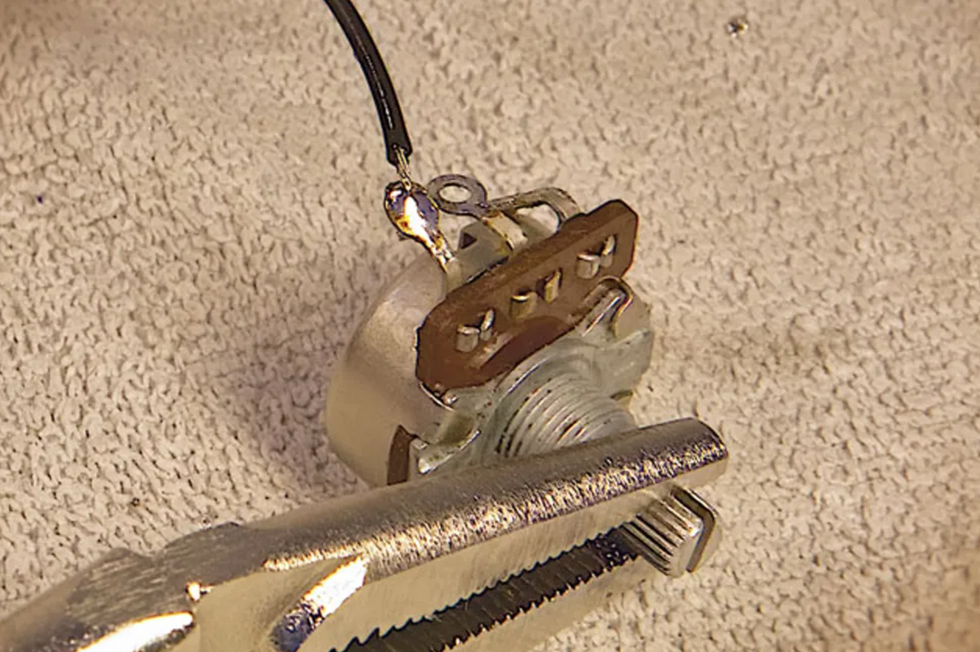

Photo 11

Here’s how it works: Stabilize your component, in this case, a pot (Photo 11). See how one lug is filled with solder? Let’s make that go bye-bye. Apply heat to the lug with a freshly cleaned soldering-iron tip.

Photo 12

When you see the solder turn shiny and molten, hold the bulb away from the lug, squeeze and hold the bulb, and then bring its tip to the lug and release the bulb. Fffffft! The molten solder goes up the tip and into the bulb (Photo 12).

Photo 13

Look at that—a nice clean lug ready for its next mission (Photo 13).

Tip: It’s good to recycle pots and parts, but never try to reuse old solder. Clean it off and start fresh.

In case you’re wondering what happens to the old solder, every few months you simply work the tip out of the bulb, shake the collected cold solder beads into the trash, and reinsert the tip into the bulb. Good to go.

When you’re working with wire and electronics, you’ll often encounter instances where you need to insulate a connection from other wires or components. For example, you want to install a favorite old pickup into another guitar. However, the pickup leads have been cut back over the years and now they won’t reach the intended switch or pot, which means it’s time to splice short extensions to the pickup leads. No problem, except if the exposed wires touch each other or other components, they’ll create a short and you’ll hear only silence (or an annoying hum).

Electrical tape will do the job to insulate the splices, but heat shrink tubing—aka heat shrink—offers a more elegant solution. To make this work, you’ll need a heat source. Some folks use a lighter, but I prefer a heat gun because I like to avoid open flame in my workshop. Heat guns aren’t expensive and they get the job done efficiently and safely.

Photo 14

The details: Designed to slide over wire of different gauges, heat shrink comes in various diameters. After you select the right diameter to comfortably slip over your wire, cut off a piece that will straddle the solder splice or joint you plan to cover. The pros suggest a length that’s about three times as long as the exposed section. Use hemostats or a clamp to temporarily hold the ends together while you gauge the length you’ll need to cut (Photo 14).

Photo 15

Next, remove the clamp, slide the heat shrink over one end of the wire (keep it far away from your hot iron) and solder the wires. When the solder has cooled, slip the heat shrink over the new joint, center it, and fire up the heat gun. The tubing will start to immediately contract around the joint (Photo 15). Don’t worry, air from the heat gun doesn’t get hot enough to compromise the solder joint. Once the tubing has completely closed up around the wire, you’re done. The joint now has a tough, new skin to protect it. —Andy Ellis

[Updated 1/13/22]