So far, we've explored ways to clean and condition your guitar with an emphasis on the fretboard, bridge, and hardware [“The Great Guitar Cleanup," December 2013]. We touched on caring for the finish, but this subject warrants further discussion.

Over time, sweat, dirt, and oils build up on the guitar's finish and slowly break it down. This causes the finish to develop a hazy film and become discolored. In addition, if your sweat has a high acid content (low PH balance), it can actually cause the finish to deteriorate, especially where you rest your arm. Sweat contains water, acids, salt, and several minerals that are corrosive to finishes and hardware. When you add in environmental issues, such as dust and pollen, it's no wonder our guitars get so filthy.

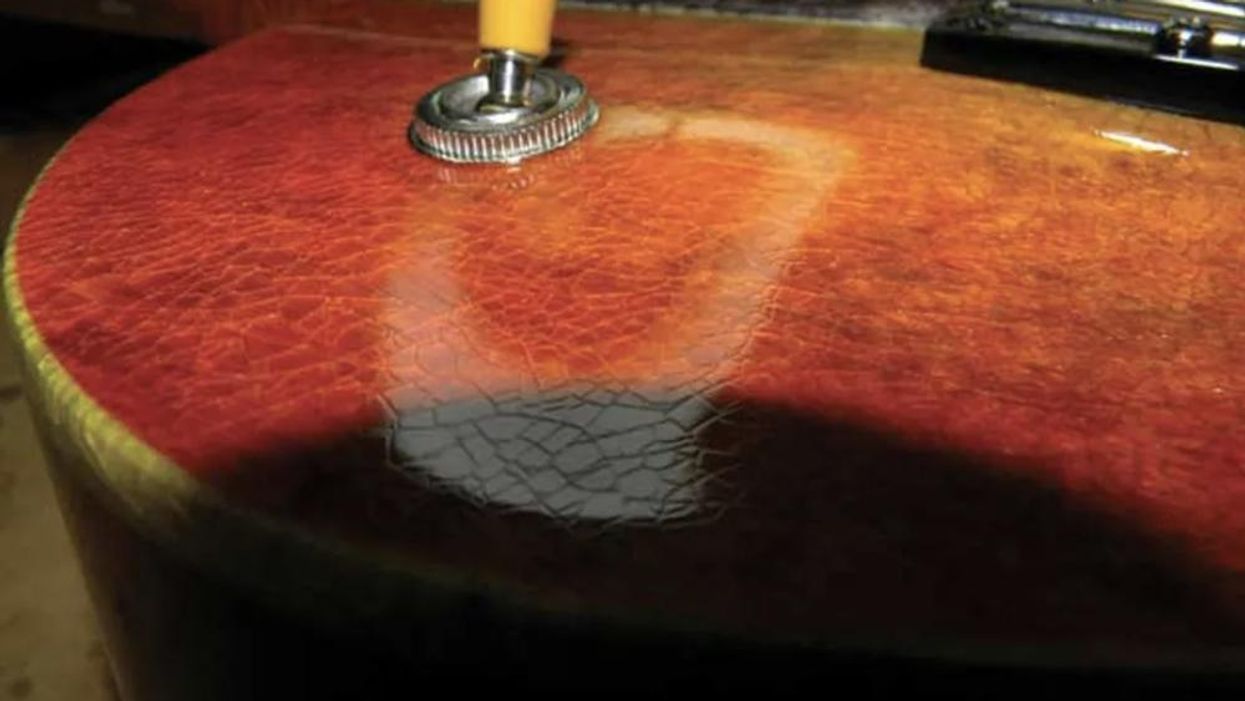

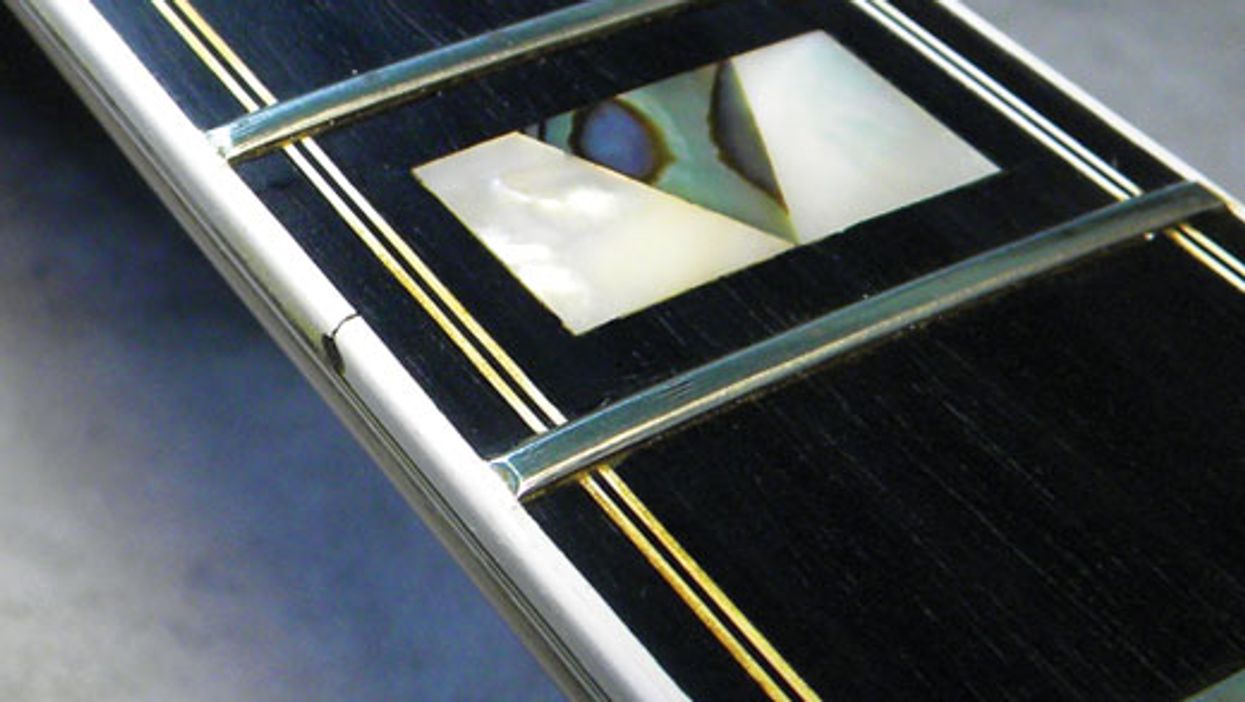

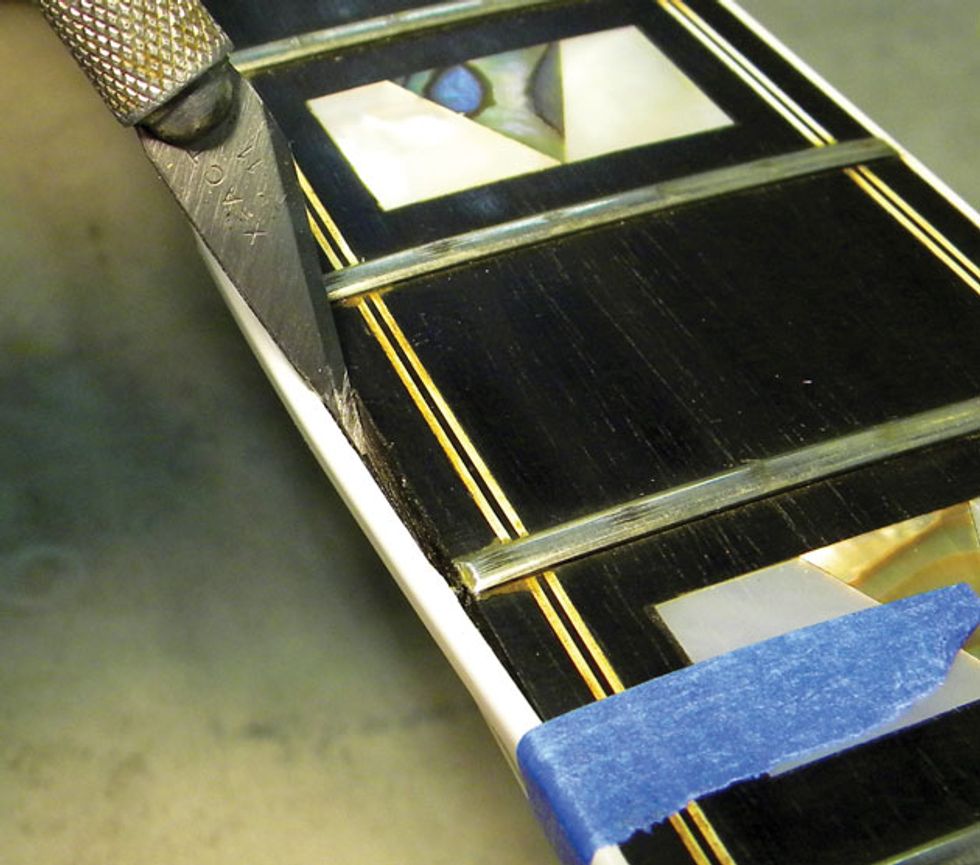

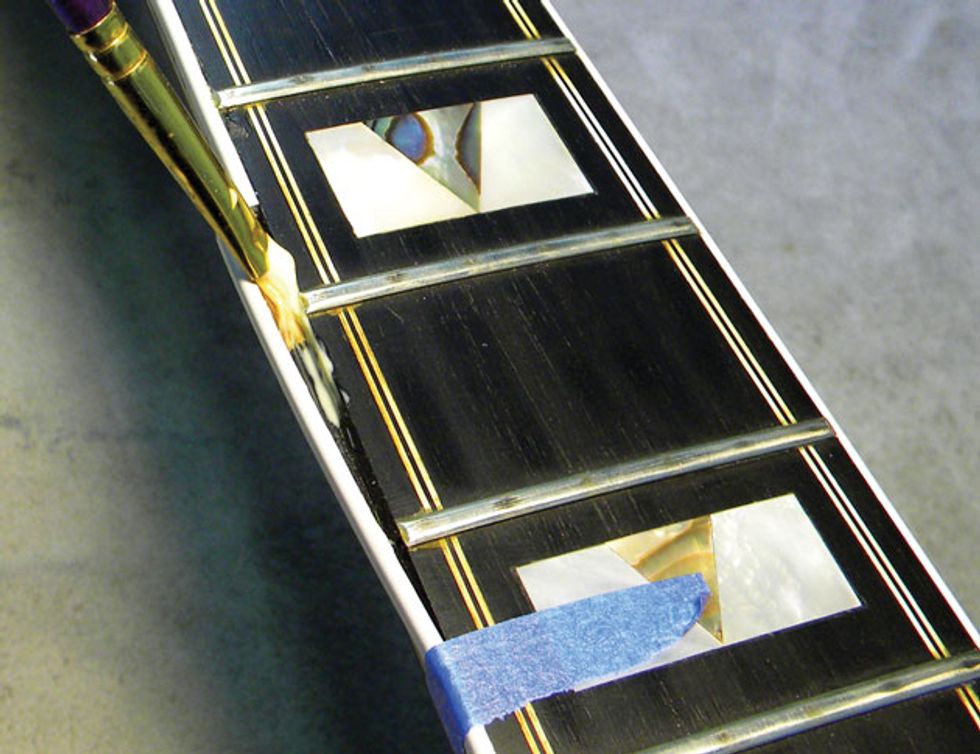

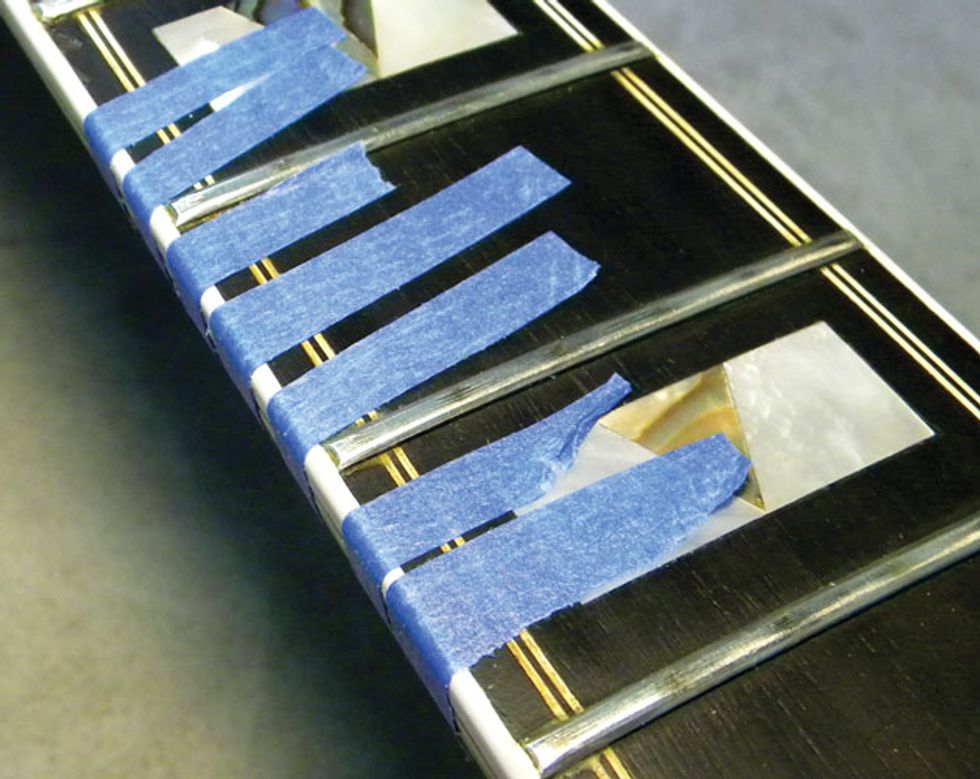

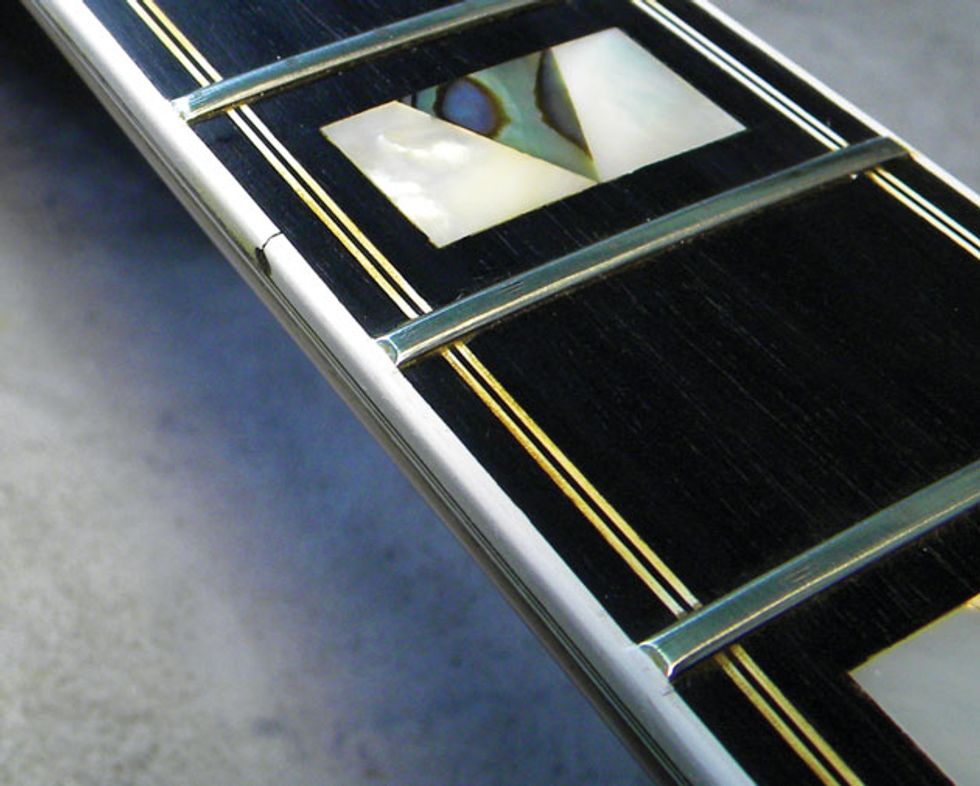

A little background. There are many different types of finishes used on stringed instruments. Vintage instruments typically sport nitrocellulose lacquer—a thin, hard finish that lets the wood resonate well. But nitro is also prone to checking and cracking over time (Fig. 1), especially when the instrument is exposed to sudden temperature and humidity changes. To combat this, many modern guitar builders and manufacturers cover their instruments with finishes that are more impervious to environmental conditions. These include urethane, acrylic, polyester, and epoxy formulations. In some cases, the switch from nitro is a way to save production costs, but builders can also be motivated by a desire to spray materials that are less harmful to the planet and workers. For example, in recent years there has been a trend toward UV-cured and water-based finishes, both of which reduce chemicals released into the atmosphere during production.

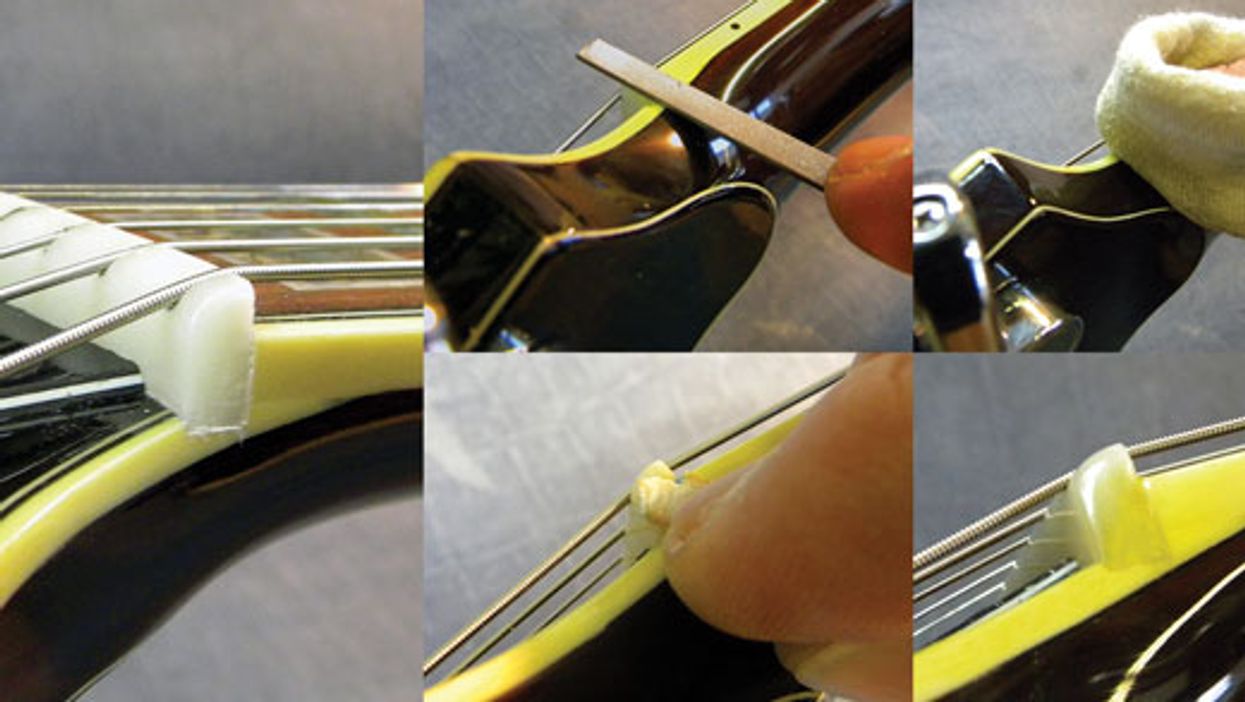

Fig. 2. A gloss finish (left) looks shiny and usually feels smooth and glass-like to the touch. Fig. 3. A satin finish (right) has a softer, less reflective sheen, allowing you to often feel the wood grain.

Modern finishes come in two styles: gloss and satin. Gloss finishes are shiny and have a glass-like look (Fig. 2), while satin finishes have a softer, hazy sheen (Fig. 3) and sometimes can actually feel "unfinished."

Cleaners and polishes. No matter what kind of finish is on your instrument, it's a good idea to keep it clean to prolong its life. There are hundreds of products on the market that claim to be the best for cleaning and polishing an instrument. The truth is many of them will cause the finish to slowly deteriorate. These cleaners contain petroleum products and solvents that can damage a nitrocellulose finish, and some polishes contain abrasives that will remove a vintage instrument's natural patina. The best guitar care products won't leave behind residue and do not contain solvents or petroleum products.

There's a debate about whether polishing a guitar is more harmful than helpful. When you polish a guitar, it creates a seal or coating that's intended to protect the finish. However, I've found that the outcome is more cosmetic than functional, and many finishes don't benefit from waxing or polishing. Polishes and waxes build up over time and can eventually dampen the sound of your guitar—almost like wrapping it in a bed sheet.

But that's not all: If your guitar has finish checking, polish will build up in the hairline cracks, and this can discolor the wood underneath or even cause the finish to flake off. Based on experience, I believe cleaning your guitar is more beneficial than polishing or waxing it. Polishing will make your guitar look better, but really doesn't benefit the finish other than making it shiny. If you feel compelled to polish your instrument, look for products that contain pure carnauba wax—it's the safest for your guitar.

Fig. 4. Professor Green's Instrument Polish (left) is a water-based "guitar soap" that cleans effectively and leaves no residue. Fig. 5. Planet Waves Hydrate (center) is formulated to condition and clean unfinished fretboards. Fig. 6. Naphtha (right)—the main ingredient in lighter fluid—is safe and effective for cleaning most finishes and hardware. However, it's toxic and flammable, so you must carefully follow the manufacturer's directions.

Three products I've found to be both safe and effective for cleaning a guitar's finish are Professor Green's Instrument Polish (Fig. 4), Planet Waves Hydrate (Fig. 5), and naphtha (Fig. 6). Though each is radically different, they can all be used with a damp cloth.

Here's the breakdown: Professor Green's Instrument Polish is a natural, water-based liquid cleaner with no harsh chemicals. I'd classify it as "guitar soap" rather than a modern polish. It does an excellent job cleaning dirt, oil, sweat, and oxidation. Being water based, it's very easy to clean up without leaving any residue.

Planet Waves Hydrate fretboard conditioner is a paraffinic hydrocarbon-based liquid. Effective for removing dirt and oils from most any finish and unfinished fretboards, it's non-toxic and non-flammable.

Which is not the case for naphtha—essentially lighter fluid. It is a gentle and high-flash solvent that's safe for most finishes. (Naphtha-saturated Q-tips do a great job cleaning rusty saddles and bridge hardware.) However, naphtha fumes and liquid are toxic to humans, so if you use it, I recommend wearing a mask and gloves. It's highly flammable, so avoid open flames!

No matter what brand or type of cleaner you choose, always avoid those that contain silicone, heavy waxes, lacquer thinner, bleach, etc. Household furniture polish and all-purpose cleaners—such as Pine Sol, Windex, and 409—will also damage your finish. The only household product that's safe to use to clean your guitar is white distilled vinegar. It will clean the finish, but do you really want a guitar that smells like a pickle?

Fig. 7. A damp paper towel (left) or microfiber cloth works well to clean a guitar's finish. Fig. 8. Use a Q-tip (right) to clean hard-to-reach nooks and crannies.

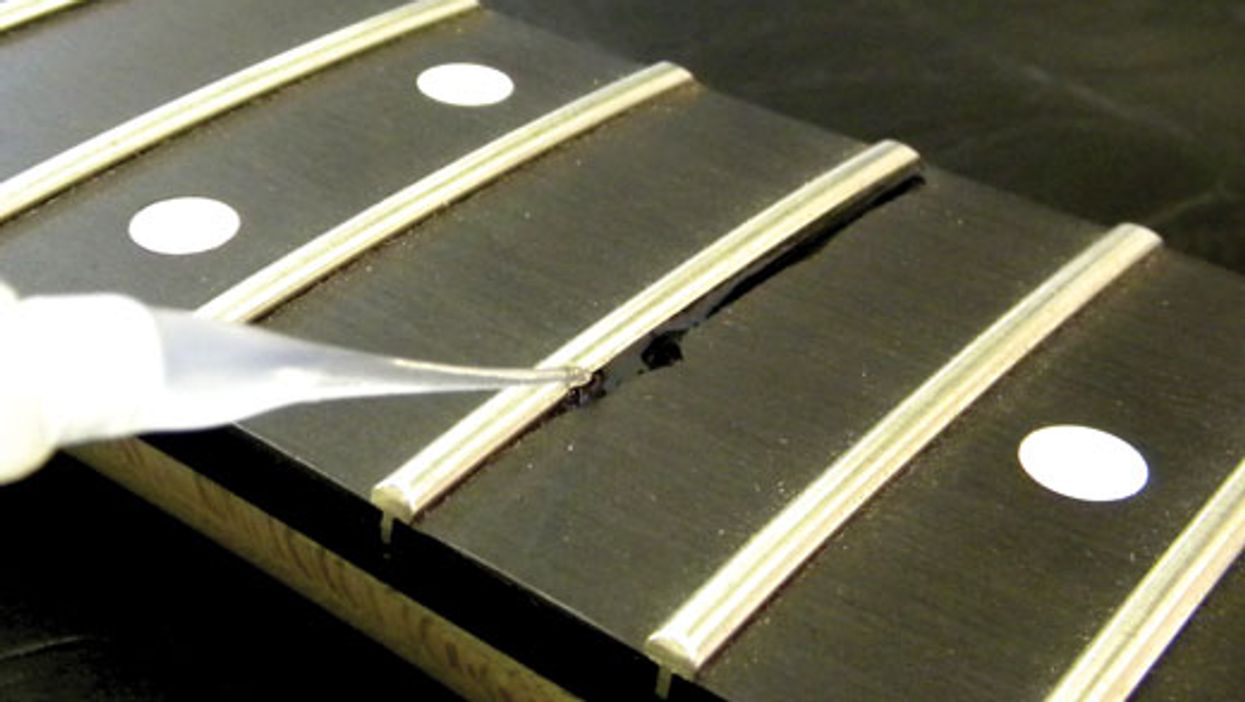

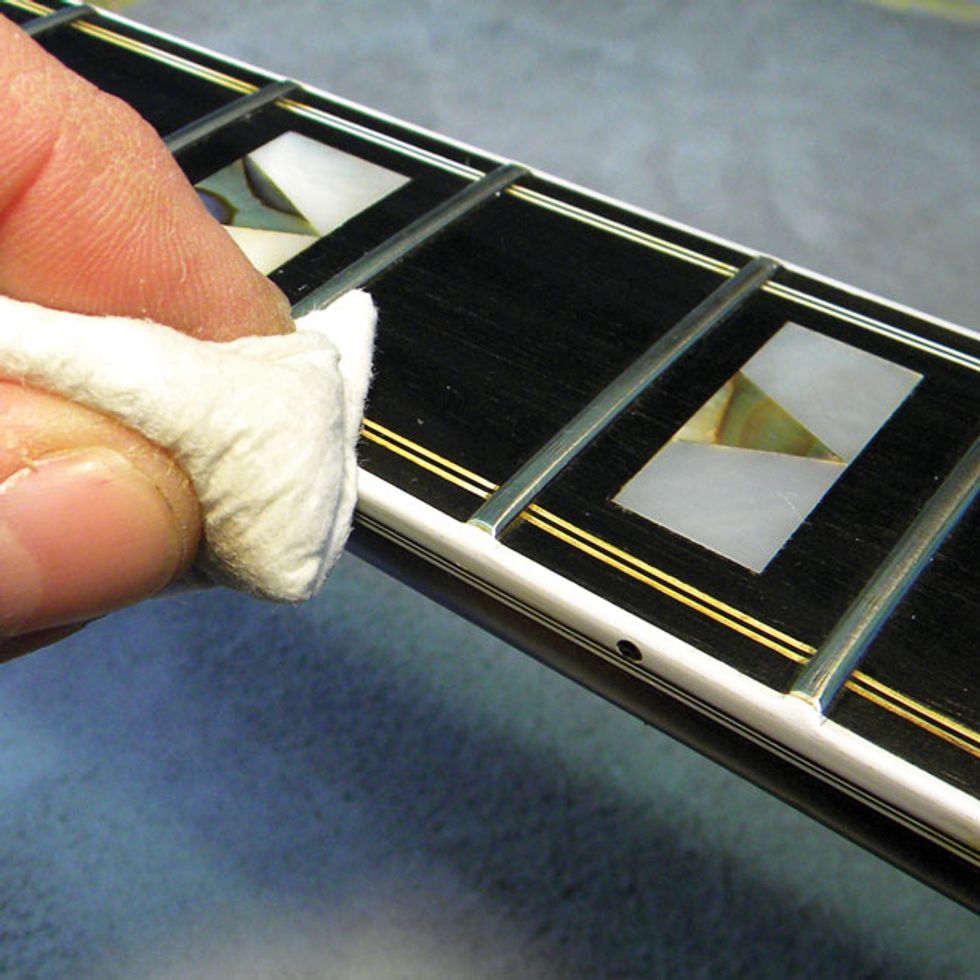

Cleaning the finish. When cleaning your guitar, I recommend using a damp paper towel or microfiber cloth. Spray or dab a little cleaner on the towel and gently wipe away the dirt (Fig. 7). Avoid saturating your guitar with water. It's okay to use a lightly damp cloth, but don't waterlog it. Use a Q-tip for those hard-to-reach areas (Fig. 8). Once the guitar is clean, go over it once more with a clean, damp cloth. That's it—quick and simple.

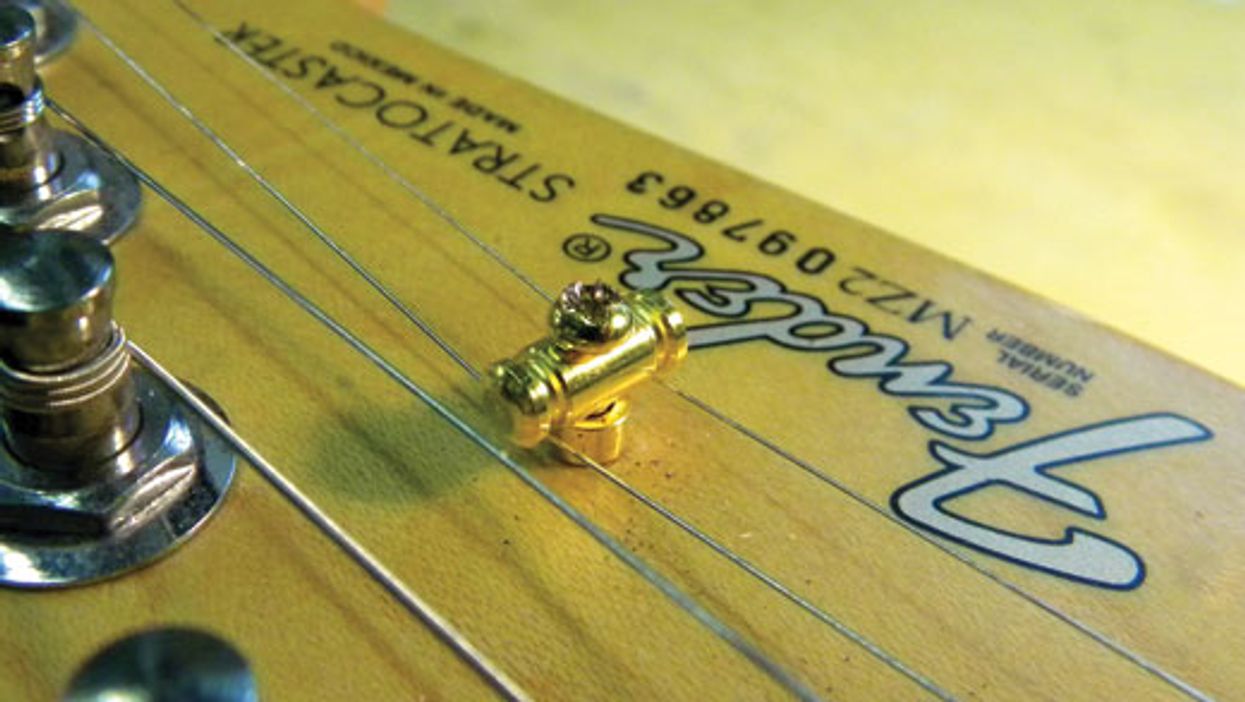

Polishing a gloss finish. If there are a lot of light scratches and swirl marks in a gloss finish, you need to decide if it's worth buffing them out. This really depends on how old the guitar is and what type of finish it has. If it's a fairly new guitar, it's okay to use a gentle buffing compound, such as Meguiar's M85 Mirror Glaze or Planet Waves Restore (Fig. 9), with a microfiber cloth to remove these marks. Keep in mind that every time you use any compound to buff out a finish, you are removing finish, so use polish sparingly and with great discretion.

Fig. 9. Buffing compounds can remove swirl marks and light scratches in a gloss finish,

but you should never buff or polish a satin finish.

Please note: If your guitar has a satin finish, never buff or polish it. Cleaning is fine, but buffing and polishing a satin finish will make it look blotchy.

Another cautionary note: If you have a vintage instrument with a nitro finish, be aware that as a normal part of the aging process, most nitro finishes will change color and develop a sheen or patina. When cleaning a vintage guitar, go easy—you simply want to remove the dirt, oils, and sweat. The underlying patina adds to the instrument's value, and removing it to make the finish shiny and pretty will devalue your guitar.

[Updated 7/25/21]