There are three different ways to configure the volume and tone controls in an electric guitar. Typically referred to as “modern," “'60s," and “'50s wiring," they perform differently and are a subject of great debate amongst tone fanatics. These wirings are often discussed in the context of a Les Paul, but the schemes apply to any guitar with a volume and tone control—whether it's a master-volume-plus-master-tone configuration, as with a Telecaster, or a guitar with individual volume and tone controls for each pickup, such as a Les Paul, ES-335, SG, and so on.

Let's examine these three systems and see how they differ. But first, some background: In a standard electric guitar, the potentiometers are used as variable resistors. We use two of the three lugs on each pot, and the tone cap is connected between the volume and tone controls. To keep it simple, we'll say each pot has an input lug, an output lug, and a third lug connected to ground.

As you close the pot—i.e., turn it counterclockwise—the wiper moves towards the grounded lug, sending more and more of your signal to ground. With the pot completely closed, all of the signal is sent to ground. In the case of a volume control, this results in silence. For the tone control, this yields the darkest tone. How dark depends on the capacitance of the connected tone cap.

With the pot completely open (turned fully clockwise), essentially the input and output are directly connected. This allows all the signal to pass through the output, which means you get full volume and, in the case of the tone control, maximum high-end chime because the tone cap has almost no influence on the sound.

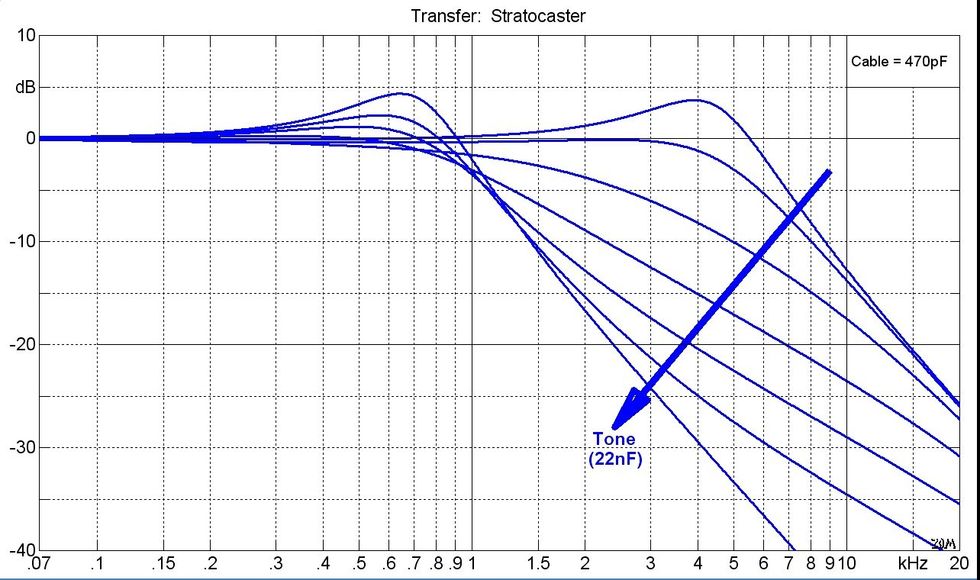

On a tone pot, instead of sending the complete signal to ground, the capacitor only sends a part of the signal to ground. The capacitance of the tone cap determines the cut-off point of the high frequencies. A low-capacitance tone cap—3300 pF, for example—will pass the least amounts of high-end chime to ground. Thus, when you roll the pot completely back, you'll hear only a subtle change in the high end. This value keeps your sound alive and vital, creating something I like to call a "warmth control." A higher capacitance value, like 0.022 µF, will roll off much more of your high end, creating a darker tone. With capacitances of 0.1 µF or even higher, your tone will be close to clinically dead with the tone pot fully closed.

Okay, now that we've done our homework, it's time to compare the three wiring schemes. We'll begin with the configuration that's so commonly used in today's production guitars that it has become a quasi-standard.

Modern Wiring

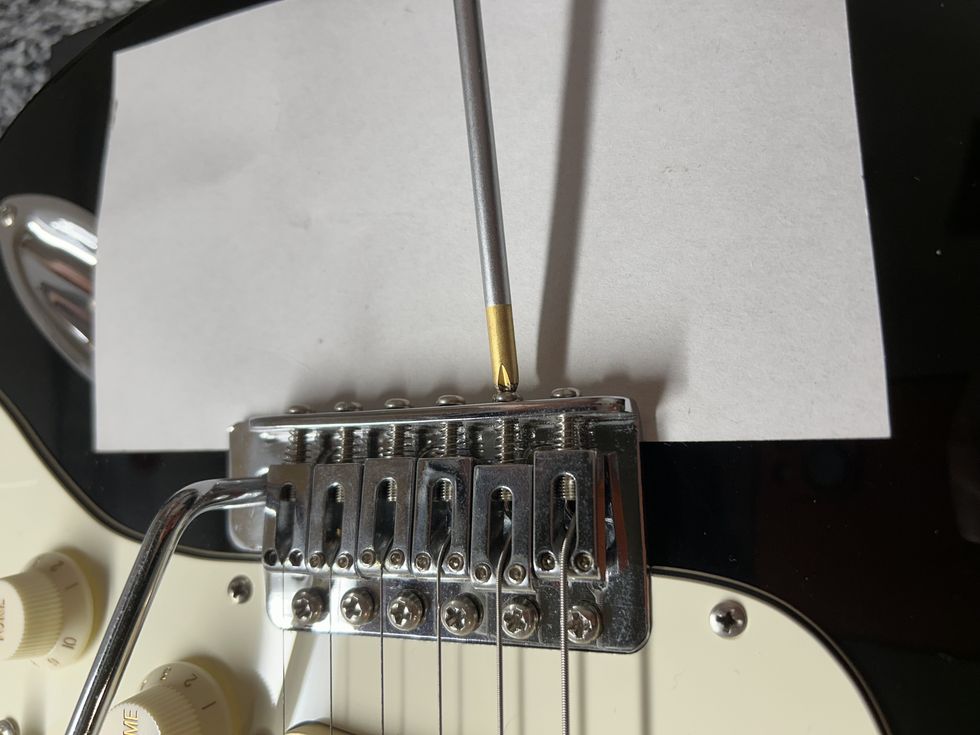

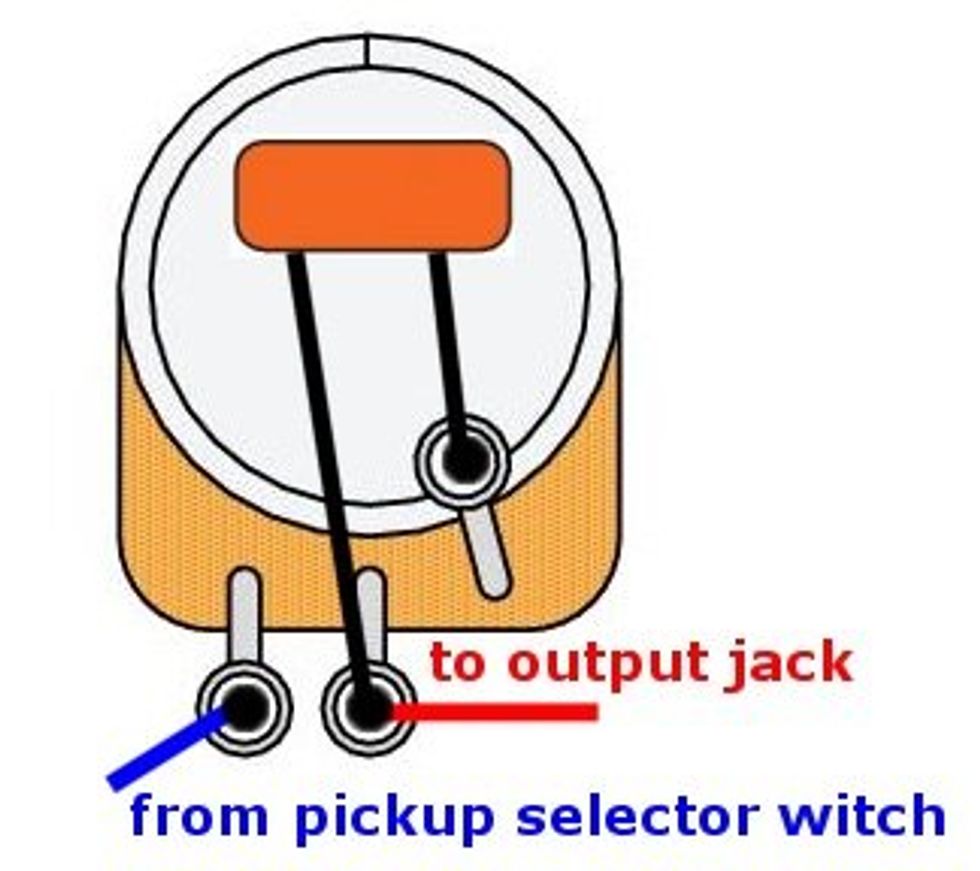

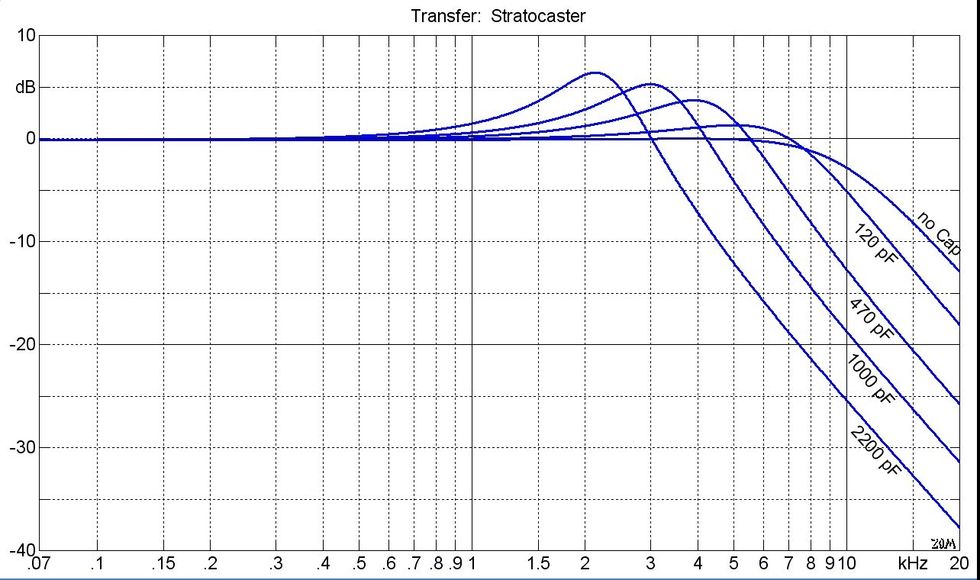

As shown in Image 1, in this wiring scheme the tone cap is connected between the volume pot's input and the tone pot's middle lug (aka wiper), which in this case is also the output. This configuration yields the behavior we've come to expect from a passive guitar. When you turn down the volume (even just a bit), the treble loss is disproportionate to the drop in volume. In other words, a small cut in volume creates a far greater loss in your guitar's treble response. That's the nature of the beast—something we all know well. There is only one real solution to combat this "volume-versus-tone" problem: active electronics. All other solutions are just a compromise … but as is often the case, some compromising can make things much better.

This natural behavior in passive electronics is not an issue for all players. Many guitarists aren't bothered by it because they've gotten used to it over the years. Others really like this effect because it gives them a second tonal color from the same pickup. "Cool—I simply roll back the volume to fatten up the tone."

That said, many players prefer to have a consistent amount of treble at any volume setting. If that describes you, putting a carefully calculated treble-bleed network on all volume pots can be a good compromise. I explain how to do this in "Diving Deep into Treble-Bleed Networks."

There's one other thing to consider: How a control responds depends a lot on the pot's taper and ratio. Today, typical audio (aka logarithmic) pots have a 90:10 ratio, which results in a more or less "on-off" effect early in the rotation, rather than a useable range of control. Our human hearing simply doesn't work like this. To feel and sound right, a control needs a different ratio—preferably 60:40 or at least 65:35, which was the standard in the '50s and '60s. Sadly, most modern guitars come equipped from the factory with 90:10 audio taper pots.

People often talk about the magical tone of late-'50s sunburst Les Pauls. Well, part of this mojo is due to the '50s wiring.

Linear pots have a different problem: Over almost the whole rotation, you won't hear a significant change in tone or volume, but when you reach the end of the rotation, the "on-off" effect suddenly appears. This is exactly the opposite of an audio pot with an ineffective taper. For more on this subject, read "Dialing in the Passive Tone Control."

Classic '60s Wiring

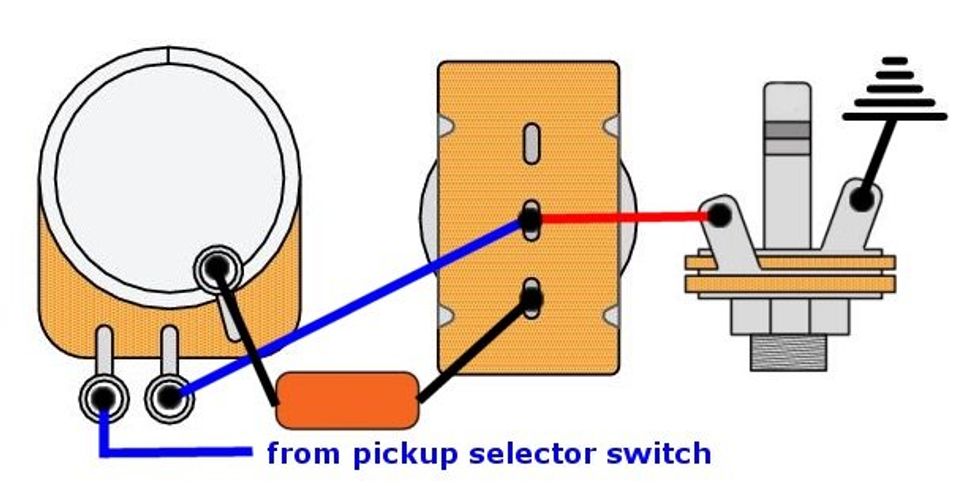

As you can see in Image 1 (middle diagram), in this configuration, the tone cap is still connected to the input of the volume pot, but on the tone pot the middle lug is now connected to ground. Electrically, the '60s wiring is completely identical to the modern wiring with the same tone, behavior, and problems. But there is one significant difference: In terms of shielding, the '60s wiring is superior to the modern wiring scheme. When electromagnetic interferences enter a guitar, they will also stray into the tone pot's unused pin and therefore into the middle lug (the wiper) in both wirings. With the wiper connected to ground, as in the '60s wiring, the interferences will stop at this point. But with the tone cap connected to the middle lug, like in the modern wiring, electromagnetic interferences will find their way through the cap and carry on.

So, compared to the modern wiring, the signal-to-noise ratio in the '60s wiring is superior. This is technical knowledge from yesteryear: The wiper of a variable resistor is connected to the low resistance part of the circuit. This knowledge was really important when designing and building tube amps, radios, and televisions, but is almost forgotten today.

So why did Gibson switch from the '60s to the modern wiring? My personal theory is that this allowed them to use pre-configured pots for both volume and tone, with the same third lug soldered to the case as the grounding point. I don't know if this is true, but if you know the reason or have another theory, please share it.

Vintage '50s Wiring

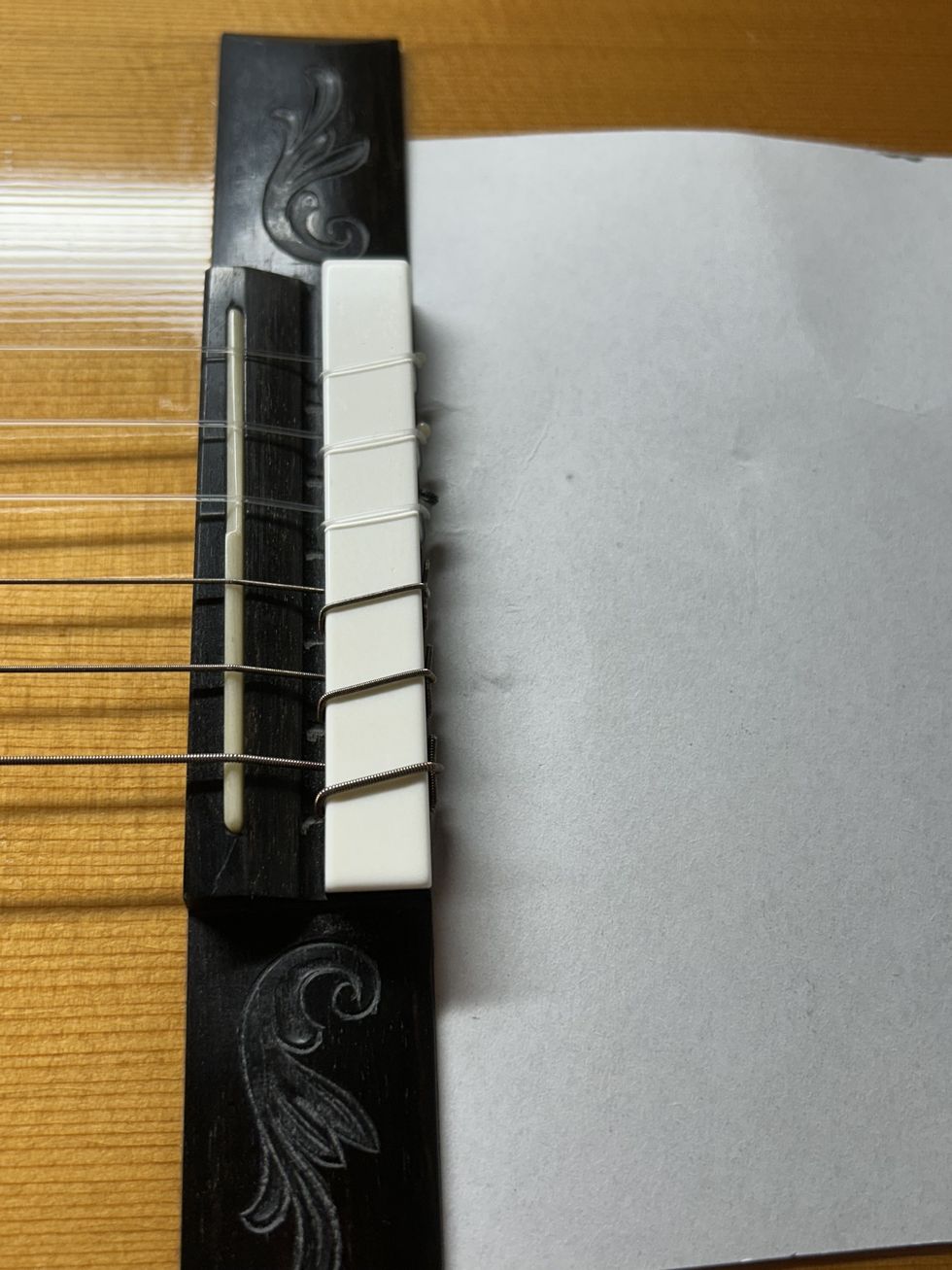

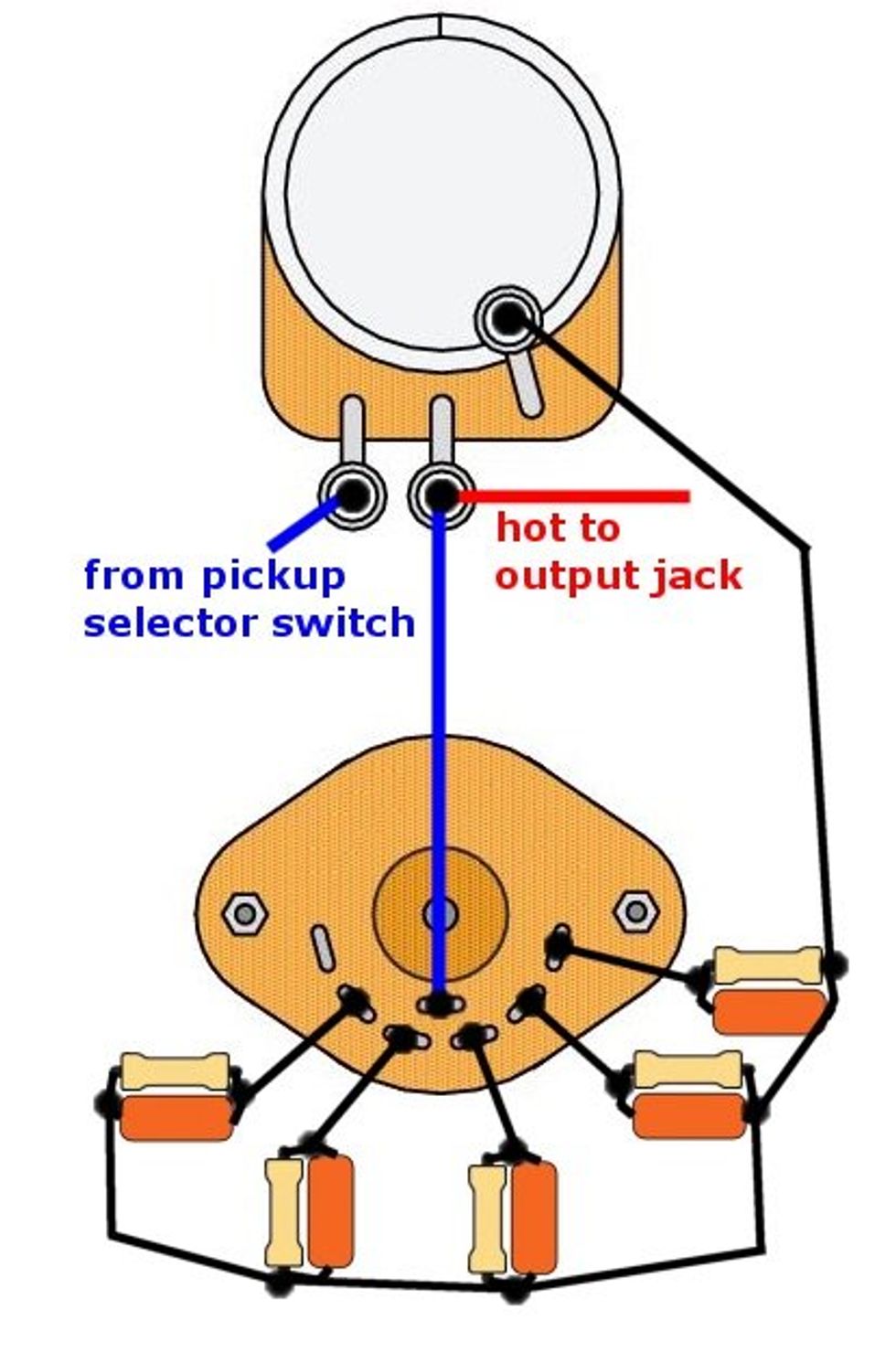

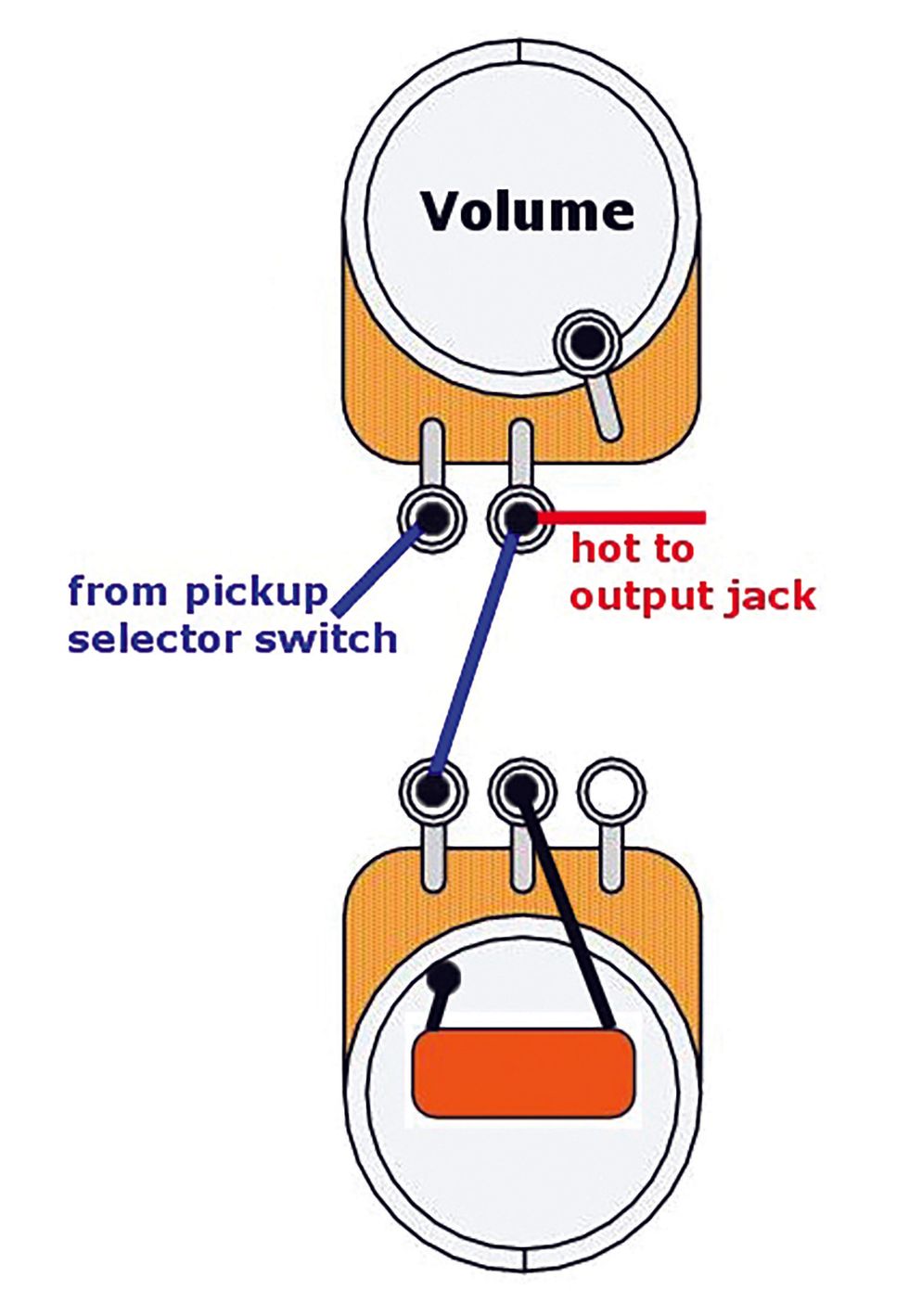

In closing, let's look at the almost legendary '50s wiring, which is by far the most discussed wiring scheme when it comes to Gibson guitars (Image 1 — bottom diagram). Here, the tone pot's middle lug is also connected to ground, like in the '60s wiring, so it also offers the benefit of superior signal-to-noise ratio. But in this case, the tone cap connects to the volume pot's output lug, rather than its input.

With the volume fully opened, the '50s wiring is identical to the modern wiring: In both versions, the tone circuit is galvanically connected to the pickup's output, so the behavior and operation are comparable. The magic starts when you turn down the volume. With the modern wiring, the tone circuit is still directly connected to the pickup, but with the '50s wiring, the tone circuit is uncoupled from the volume, which is now electrically located between the pickup and the tone circuit. Because the tone circuit can no longer react directly to the inductance of the pickup, no resonance superelevation and no resonance shift can happen at this point. With the tone pot almost closed, the bass frequencies will be relatively raised—perfect for creating the "woman tone" that's often associated with Cream-era Eric Clapton.

What's so special about the '50s wiring? It will influence the guitar's performance in three major ways:

- The overall tone gets stronger and more transparent. It's difficult to describe, but I think of it as more "in your face."

- The typical treble loss that occurs when rolling back the volume is greatly reduced, and both the volume and tone controls react more smoothly and evenly without the typical hot spots. As a side effect, it's easier to clean up an overdriven amp by simply rolling back the volume on your guitar a bit.

- The tone and volume controls interact with each other—something you may know from certain early Fender tube amps. When you change the volume, the tone also changes a little bit and vice versa. Such interaction may feel strange at first, but it only takes a few minutes to get used to.

People often talk about the magical tone of late-'50s sunburst Les Pauls. Well, part of this mojo is due to the '50s wiring. The guitar responds differently—notes seem to "bloom," as if they're opening up after leaving the guitar. Why not give it a try? You might love it.

Next time, we'll resume our exploration of different types of guitar wire and how to use and handle them, so stay tuned. Until then ... keep on modding!

[Updated 9/9/21]