In the early 1970s, mobile recording studios were the size of trucks. Actually, they were trucks. The first famous example—the legendary Rolling Stones' Mobile Studio—sat atop the chassis of a British Motor Corporation Laird lorry.

Today, a mobile studio can be as small as a laptop, tablet, or smartphone. Throw in the growing power of compact stand-alone recorders, and you have an overwhelming number of potential tools for recording that can fit in a backpack—or back pocket. The combination of power and portability is redefining our very understanding of the concept of mobile recording.

“[A mobile device] is capable of recording everything from a songwriter's demo to a fully finished track, but in its own way and time," says Vincent Leonard, co-author with Thomas Rudolph of The iPad in the Music Studio: Connecting Your iPad to Mics, Mixers, Instruments, Computers, and More! and Musical iPad: Creating, Performing & Learning Music on Your iPad. “It can [also] function as an extension of a desktop system"—allowing you to work on projects remotely and finish them in your home studio.

“I would define [mobile recording] as recording music anywhere in the world outside of a commercial studio or your own home setup," says Rich Tozzoli, whose credits include production and engineering for artists like Al Di Meola, Ace Frehley, and David Bowie, as well as composing original music for Fox, the NFL, Pawn Stars, Duck Dynasty, and others. “For mobile situations, less complicated recording systems are better."

Choosing a mobile recording device is about balancing factors like portability, simplicity, fidelity, and flexibility. The sweet spot is often less about the equipment than it is about your working method and the task at hand. Rather than make some blanket recommendations, let's look at things to consider for a number of common situations.

Capturing Ideas: Keep It Simple—and Light

The Muse can be a cruel mistress. She shows up unannounced—and she doesn't like to stick around. So while she's there, you'd better be ready to grab everything she's giving you. For mobile Muse patrol, you need a recorder that's easy to keep close at hand and that gets ready to track as quickly as possible.

A standalone recorder or a smartphone with a basic recording app can each work well here. Even a compact camera, like a GoPro, can serve you well. But no matter what hardware you're using, readiness is more important than any other feature. Your device needs to be charged and it needs to have enough available storage memory to capture the idea. Most important, you have to have the device with you. A small stand-alone recorder is great—if it's handy. But that's a big if. A smartphone, on the other hand, is likely to be within arm's reach most of the time. How else would you play Candy Crush Saga while you're on a conference call? So even if you do have a stand-alone recorder, it pays to set up your phone for recording as well.

How elaborate does that setup need to be? Again, readiness is your goal. You can plug in an external high-end mic for better sound. There are a growing number of options from leading manufacturers like Shure, Sennheiser, Audio-Technica, and others. But if it means shifting focus from the creative flow, don't bother. You don't need great sound to capture an idea.

That said, recording quality isn't completely unimportant. You don't want things to be so distorted or lo-fi that you can't hear that brilliant, complex chord you just played by accident. With a stand-alone recorder, this isn't much of an issue as long as you position the mic close enough to the source and adjust the input levels accordingly. If it has direct inputs and your guitar has a pickup, all the better.

Using a Shure MOTIV MV88 stereo condenser mic and free MOTIV iOS app, you can add quality audio to iPhone videos of rehearsals and impromptu performances.

If you're using a phone, tablet, or computer, the device's internal mic may even be okay. Remember, you're looking for clean, not studio quality. The app you're using can make a difference, however. The audio apps that come with most phones are usually designed for voice. They tend to offer limited frequency response and store recordings in space-saving (but bad-sounding) low-resolution audio files.

You're actually better off using your phone's video camera to capture sound. The sound quality can be quite good, but because video is data intensive, the file will be huge. Use the camera for quick captures, not long sessions. I've run out of storage space in the middle of recording, didn't realize it, and lost some ideas as a result.

So it pays to invest in a basic audio-capture app designed for music. One of my favorites happens to be free. We wrote about Spire in “Recording Roundup 2016." What makes it especially good for mobile use is that itboots fast, records up to 4 tracks of high-resolution audio, and provides a number of file-sharing tools. Its DSP enhances the sound of the phone's built-in mic, and while it won't make the mic sound better than a quality external interface or microphone, it's quite an improvement over the unprocessed input.

If you're using a portable device, make it a point to copy the files from your device regularly and keep them organized. Not only will this make it easier to back things up, it frees memory on your recorder, which can become an issue more quickly than you might think—especially with tablets and smartphones that also store games, movies, books, and other apps.

A number of mobile recording devices, including IK Multimedia's iRig series, are designed specifically for guitar.

Doing Homework: Stand-alone Devices Rule

If you're serious about performing, few things are as valuable as the “homework tape"—a simple but clear recording of your band's practices and performances. I always think of these as “capture" sessions more than recording sessions. You want an accurate representation of the music, not a self-conscious recording.

As a result, the ideal tool will be something that can run happily in the background, without forcing you to stop. Recording time and ease of use are primary considerations, but flexible inputs and other extras are welcome additions.

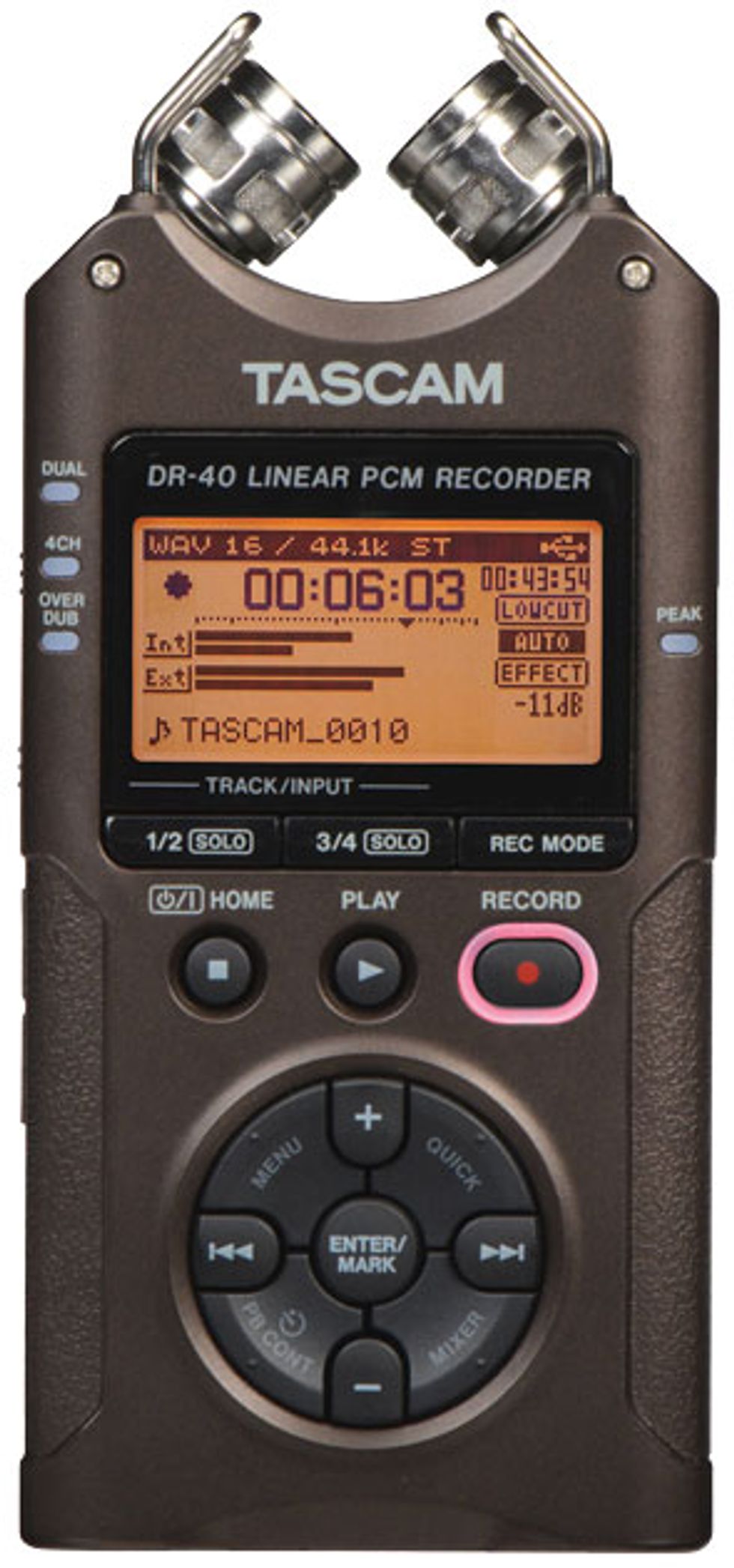

Stand-alone recorders—especially those with built-in mics and removable storage—can be ideal for this. You can set the machine up some distance away, point its mics at the music, hit record, and forget about it for the rest of the night.

A mobile phone or tablet may be able to get you through an entire session, but for piece of mind, a stand-alone recorder is probably a better choice thanks to its larger storage space and the fact that it won't be interrupted by phone calls, texts, and other intrusions that can plague phones and tablets.

And avoiding interruptions is the key: Most stand-alones—even those at budget prices—can record in both compressed (like MP3) and uncompressed (AIFF or WAV) audio formats. And although the uncompressed audio offers higher fidelity, you'll save space—and therefore increase potential recording time—by using a compressed format. When you're tracking with mics from across the room, you'll hardly notice the trade-off in sound quality.

In addition to storage, you also want to make sure that your device isn't going to run out of juice midway through the session. If it's an option, run it on a plug-in power supply. If you are using batteries, make sure they're fresh or freshly charged.

When it comes to placing the unit and setting your recording levels, that's a matter of trial and error. If you're recording in the same space regularly (such as a rehearsal studio), pick a spot and use it as consistently as possible.

Take the time to do a quick level check by recording a song at the start of rehearsal or during soundcheck. Listen back, and adjust your input levels and placement as needed. I always keep the levels just a little lower than optimal because bands tend to get louder as the night progresses.

Here's an idea to consider when you're capturing a live show: If your recorder can use its internal mics and external line inputs simultaneously, combine the mics with the feed coming from the PA's front-of-house mix. This can be especially good if each input is saved to its own audio file, because you can then upload the files to a digital audio workstation (DAW) and mix the room sound from the mics with the board mix from the direct feed.

Multitracking: Apps and Interfaces To Go

Sometimes I think multitrack recording should be called “multi-personality" recording, because so many different approaches fall under the multitrack umbrella. Are you working alone and building tracks one at a time? Recording a band? Are you only recording acoustic and amplified instruments like voice guitar, drums, and tuba? Or are you using electronic and software instruments along with your guitar?

As you're putting your system together, consider what you hope to do with the tracks after you record them. Do you plan to produce and mix complete tracks with your mobile rig? Or are you going to hand your tracks off for later overdubs and mixing?

Although some stand-alone recorders can handle multitrack recording, we'll focus on more “production" oriented setups—DAW software running on a computer or mobile device that's mated to an audio interface. For guitarists, the software might include the recording app itself along with amp-modeling plug-ins, other effects, software instruments, and more.

If you're looking for a small footprint, you'll find a number of options for iPhone or iPad. Apple's own GarageBand ($4.99) is built for these devices, and offers easy compatibility between mobile and computer versions of the software, as well as Apple's professional DAW, Logic. PreSonus Capture ($9.99/free demo) offers basic multitrack recording in an elegant interface. If you're willing to spend more, $24.99 will get you Steinberg's Cubasis for iPad (a streamlined yet powerful version of the company's Cubase Pro PC/Mac sequencer), or Auria by WaveMachine Labs, an audio-focused app that seems to be modeled on Avid Pro Tools.

Although these tools can be used to produce complete mixes, they are limited to some degree by the platform. “Tech always has a tradeoff," Leonard says. “An iPad, for example, offers a lot of production power in a small package, but that comes with restricted storage and a limited use time unless you're able to charge the unit while you work. When you finish a session, you will need to transfer your tracks so the device doesn't fill up. That process is a little slower than copying files over a computer network. Get into the habit of transferring files in any free time. Because once you've filled up your device, you can't work until you free up more space."

For production work, an external interface and a quality external mic is definitely recommended. On the lower end of the price scale, you'll find options that use the mobile device's headset input. This category includes a number of devices designed for guitar, including IK Multimedia's iRig series, the RapcoHorizon iBLOX, and others, which have 1/4" connections for an electric guitar or bass, as well as a jack for stereo headphone monitoring. But the headset input still uses your phone's analog-to-digital converters, so the sound isn't great.

For serious recording, an external interface that connects to the phone's USB input (currently Lightning for iOS devices) will offer much better sound. The options continue to grow, including several that boast instrument inputs for direct recording of your guitar or bass. Many of these compact interfaces can also be used with a computer, making them both economical and flexible. Guitar-friendly models include IK Multimedia's iRig PRO, Fender Slide Interface, Line 6 Sonic Port VX, and Apogee Jam (among others). You'll also find all-purpose interfaces that let you plug in a 1/4" cable, standard microphone, or use an internal mic. The compact Apogee One, for instance, has a built-in mic as well as a removable harness with 1/4" and phantom-powered XLR inputs. The Focusrite iTrack Pocket iOS interface acts as a dock and has built-in DSP. PreSonus AudioBox has a more traditional USB audio interface form factor and connects to both computers and mobile devices.

If the USB interface has its own power supply, it can even be used to charge your mobile device—something that seems like an “extra" when you read the features list, but turns out to be a big deal when you're in the field.

A stand-alone recorder, like the Tascam DR-40, is ideal for making a “homework tape"—a clear recording of your band's practices and performances. The advantage? Larger storage space and the fact that a dedicated recorder won't be interrupted by calls, texts, and other intrusions that can plague phones and tablets.

For a mobile setup that can come close or even match a home or project studio, a laptop and interface seems like the way to go. It can still be portable, and it's easy to add or subtract peripherals as needed. If you want something truly portable and don't need to record more than two independent sources at a time, a small bus-powered USB interface should have you covered.

“Make sure that all components are of good quality and work well together," adds Steve Oppenheimer, VP of marketing at PreSonus, which makes audio interfaces for computers and mobile devices, digital mixers, and software. “In addition to selecting a quality, bus-powered interface—you want bus power because an interface that requires AC power is not entirely mobile—you'll need a good microphone, headphones, and cables, as well as recording and production software and a reliable laptop or tablet computer, such as an iPad."

If you need more inputs, there are plenty of mid- to high-end interfaces to choose from. A good unit capable of recording eight or more individual tracks will fit in a single rack space and can be shoved into a laptop bag in a pinch. If the interface has built-in mic preamps and instrument inputs, it can serve as the sole peripheral (minus mics, headphones, and cables). With eight inputs, you can record a whole band, capture an electric-acoustic guitar on two independent tracks using its internal pickup and an external mic, and much more.

Packing for Tracking: Be Prepared

According to Tozzoli—who regularly does pro-level sessions away from his main studio—the specific equipment you choose for your mobile rig is less important than the way you organize your gear. One missing piece—no matter how small—can sabotage a session.

“For me, the essentials include a computer—usually a laptop—interface, speakers, headphones, and all the necessary cables," he explains. “I have several setups that vary in scope. The simplest is a MacBook Pro with a Universal Audio Apollo Twin interface running Pro Tools 12 and Propellerhead Reason. The next level up is a Universal Audio Apollo 16, with a variety of FireWire outboard eight-channel preamps from Focusrite and Audient, again running Pro Tools 12.

“With either rig, whenever I go remote, I like to bring the same gear, packed in exactly the same way—every time. For example, in my laptop bag, I have the charger, the external hard drive, all cables and adapters, and even the iLoks in the same place. That way, if something is missing, it has a better chance of registering with just a quick glance.

“I also create a written checklist in my iPhone to make sure I have everything. It gets easier the more you do it, and now its second nature."

A few years ago, a studio like the one Tozzoli just described would take a desktop computer and card-based audio interfaces, not to mention a rack of gear. Now you can do it all with a laptop. Will tablets and smartphones go the same way?

“When I started working with music on the iPad four years ago I thought it might become the new Portastudio," Leonard says. “When we started writing The Musical iPad, the industry was exploding with products. In some ways, it's like watching a repeat of 30 years ago when MIDI and the computer were starting to come together—dealing with the limitations of the hardware and watching the software developers ask for more power and flexibility."

Making albums on iPads

In late 2011, the music industry went abuzz after learning that Gorillaz's album The Fall had been recorded on co-founder Damon Albarn's iPad during a U.S. tour. “I literally made it on the road," Albarn told the Guardian. “I didn't write it before, I didn't prepare it. I just did it day by day as a kind of diary of my experience in America."

Albarn used a wide range of apps to make the album (which was mixed when he got back to England), but indie punk duo the Ultramods described how they only needed GarageBand for iPad to make Underwear Party. “I see [the GarageBand app] as an everything-combined-into-one package," lead singer Max “Bunny" Sparber told Wired magazine. “Both new musicians and professional musicians are going to be very surprised with what they can do with it."

YouTube It

Blur frontman Damon Albarn recorded his side project Gorillaz's 2011 album, The Fall, entirely on his iPad while on a U.S. tour, using a wide variety of apps including AmpliTube, SoundyThingie, StudioMini XL Recording Studio, and Bassline.

These days, there's a lot less gee-whiz factor around mobile devices, so it's unlikely that recording on a tablet is going to be any more central to an album's publicity campaign as recording with a laptop. But whether mobile devices are used as a complete “studio" or as a part of the production process, it's clear that pros are finding a place for such gear in their work.

In a detailed 2014 MacWorld article, Andrea Pejrolo, Assistant Chair of the Contemporary Writing and Production Department at Berklee College of Music, explains how he used the iPad as a complete production system to record sessions for indie artist and composer Ella Joy Meir. While admitting that the iPad had some limitations compared to laptops in terms of storage, he notes that there are also advantages that go beyond its small form factor. “If you are planning to record in a space where your sound engineer and performer are in the same room, the iPad has the advantage of being dead quiet," he says. “And then there's the cost: iOS offers the convenience of a touch display and the portability of a laptop, but with a much smaller price tag."

With an iPad, recording software, and a battery-operated interface like the Apogee One, you can record wherever and whenever inspiration strikes.

The Ins and Outs of Mobile Inputs

The idea of recording an album on a phone or tablet seems like more fun than hauling around a laptop or stand-alone recorder. Computers are for work; smartphones and tablets are for play.

Then again, there's nothing fun about recording music and having it sound like, well, you recorded it on a cell phone. Fortunately, a growing number of manufacturers are bringing better—and, in some cases, pro-level—audio quality to mobile devices. As with computer interfaces, these connect to a data port—currently, the majority work with Apple's Lightning—and offer analog-to-digital-to-analog conversion. Among them are a number of options offering 24-bit resolution at sample rates as high as 192 kHz. (All prices listed are street.)

Apogee—known for making high-end A/D converters and interfaces—was one of the first computer audio companies to get serious about mobile. The development shows in their latest array of mobile accessories ranging from the $129 Jam 96K to the $1,395 Quartet. The latter boasts four mic preamps, an 8-channel Lightpipe I/O, and the ability to work with both Mac and iOS devices.

PreSonus has affordable and compact interfaces that can connect directly to both computers and iOS devices, including the 2x2 AudioBox iTwo ($99), which offers both audio and MIDI I/O and comes with the company's free multitrack mobile app, Capture Duo.

Shure made a splash last fall by introducing MOTIV series microphones and interfaces designed specifically for the latest generation of iOS devices. Priced between $69 and $199, the series includes mono and stereo mics, as well as the MVi, a guitar-friendly interface that can also work with a computer. Other pro audio mic makers have been going mobile as well. Sennheiser offers a pair of clip-on mics that seem targeted more to video work than music, but with Apogee converters, the $199 ClipMic Digital does the trick.

Rode's lineup of iOS mics includes two stereo condensers: the iXY-L ($199) has a Lightning connector, while the iXY ($149) is both less expensive and sports the increasingly hard to find 30-pin connector of old. And Blue Microphones' Mikey Digital ($99) can mount directly to an iOS device and has an auto-sensing level and multiple gain settings.

In addition to making a number of popular handheld stand-alone recorders, Zoom recently released the iQ series of versatile Lightning-compatible mics, ranging from $69 to $99. Focusrite's stable of iOS interfaces includes the two-channel, 24-bit/96 kHz iTrack Dock ($199), which lets you dock and charge your iPad while feeding it mic, line-level, or MIDI signals.

While IK Multimedia's original iRig series connected via the headphones jack, the company's new iRig Pro series, topped by the two-channel PRO DUO ($199), uses Lightning for better audio quality. The Line 6 Sonic Port ($99) offers both Lightning and 30-pin connections and comes with a mobile version of the company's POD amp/effects modeling app.

You'll also find an array of compact USB interfaces and microphones that can be made iOS compatible with an Apple Camera Kit or Lightning-to-USB Camera Adapter, such as Apple's $31 MD821AM.

Among the latest is Steinberg's new UR22mk2 ($149), which can record at sample rates as high as 192 kHz and comes with Cubasis LE, an iOS version of the company's popular pro-level DAW, Cubase. Roland's $179 Duo-Capture EX offers 48 kHz A/D recording, MIDI, and more. The Audio-Technica AT2020USBi ($199) mates a large-diaphragm side-address condenser with a USB interface that can work with Windows, Mac, and iOS devices.

Finally, if you're looking to make your iOS recording rig part of your performing setup, you'll find a few mobile interfaces in the pedal format. Sonoma Wire Works $299 GuitarJack Stage has four footswitches, high-Z inputs specifically designed for guitar and bass, and knobs that can be used to control iOS or computer amp modelers.