Electric guitar pickups weren’t necessarily supposed to turn out the way they did. We know the dominant models of single-coils and humbuckers—from P-90s to PAFs—as the natural and correct forms of the technology. But the history of the 6-string pickup tells a different story. They were mostly experiments gone right, executed with whatever materials were cheapest and closest at hand. Wartime embargos had as much influence on the development of the electric guitar pickup as did any ideas of function, tone, or sonic quality—maybe more so.

Still, we think we know what pickups should sound and look like. Lucky for us, there have always been plenty of pickup builders who aren’t so convinced. These are the makers who devised the ceramic-magnet pickup, gold-foils, and active, high-gain pickups. In 2025, nearly 100 years after the first pickup bestowed upon a humble lap-steel guitar the power to blast our ears with soundwaves, there’s no shortage of free-thinking, independent wire-winders coming up with new ways to translate vibrating steel strings into thrilling music.

Joe Naylor, Chris Mills, and Pete Roe are three of them. As the creative mind behind Reverend Guitars, Naylor developed the Railhammer pickup, which combines both rail and pole-piece design. Mills, in Pennsylvania, builds his own ZUZU guitars with wildly shaped, custom-designed pickups. And in the U.K., Roe developed his own line of hexaphonic pickups to achieve the ultimate in string separation and note definition. All three of them told us how they created their novel noisemakers.

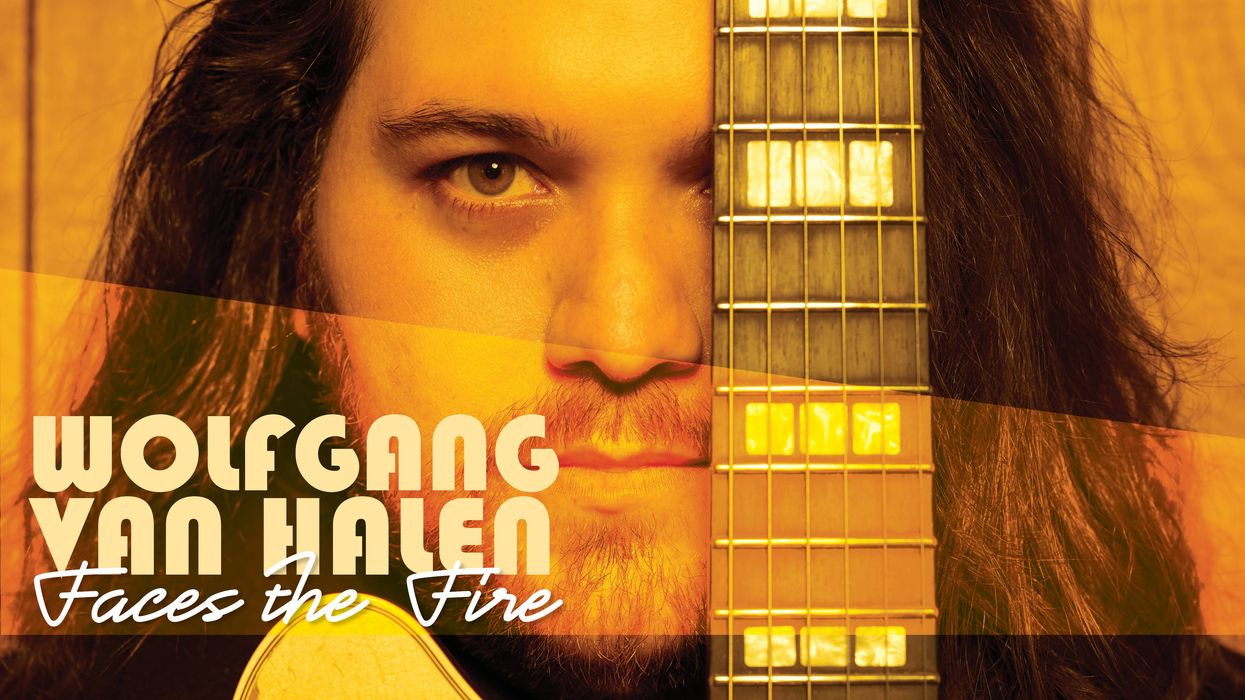

Joe Naylor - Railhammer Pickups

Joe Naylor, pictured here, started designing Railhammers out of personal necessity: He needed a pickup that could handle both pristine cleans and crushing distortion back to back.

Like virtually all guitar players, Joe Naylor was on a personal tone quest. Based in Troy, Michigan, Naylor helped launch Reverend Guitars in 1996, and in the late ’90s, he was writing and playing music that involved both clean and distorted movements in one song. He liked his neck pickup for the clean parts, but it was too muddy for high-gain playing. He didn’t want to switch pickups, which would change the sound altogether.

He set out to design a neck pickup that could represent both ends of the spectrum with even fidelity. That led him to a unique design concept: a thin, steel rail under the three thicker, low-end strings, and three traditional pole pieces for the higher strings, both working with a bar magnet underneath. At just about a millimeter thick, rails, Naylor explains, only interact with a narrow section of the thicker strings, eliminating excess low-end information. Pole pieces, at about six millimeters in diameter, pick up a much wider and less focused window of the higher strings, which works to keep them fat and full. “If you go back and look at some of the early rail pickups—Bill Lawrence’s and things like that—the low end is very tight,” says Naylor. “It’s almost like your tone is being EQ’d perfectly, but it’s being done by the pickup itself.”

That idea formed the basis for Railhammer Pickups, which began official operations in 2012. Naylor built the first prototype in his basement, and it sounded great from the start, so he expanded the format to a bridge pickup. That worked out, too. “I decided, ‘Maybe I’m onto something here,’” says Naylor. Despite the additional engineering, Railhammers have remained passive pickups, with fairly conventional magnets—including alnico 5s and ceramics—wires, and structures. Naylor says this combines the clarity of active pickups with the “thick, organic tone” of passive pickups.

“It’s almost like your tone is being EQ’d perfectly, but it’s being done by the pickup itself.” —Joe Naylor

The biggest difficulty Naylor faced was in the physical construction of the pickups. He designed and ordered custom molds for the pickup’s bobbins, which cost a good chunk of money. But once those were in hand, the Railhammers didn’t need much fiddling. Despite their size differences, the rail and pole pieces produce level volume outputs for balanced response across all six strings.

Naylor’s formula has built a significant following among heavy-music players. Smashing Pumpkins’ Billy Corgan is a Railhammer player with several signature models; ditto Reeves Gabrels, the Cure guitarist and David Bowie collaborator. Bob Balch from Fu Manchu and Kyle Shutt from the Sword have signatures, too, and other players include Code Orange’s Reba Meyers, Gogol Bordello’s Boris Pelekh, and Voivod’s Dan “Chewy” Mongrain.

Chris Mills - ZUZU Pickups

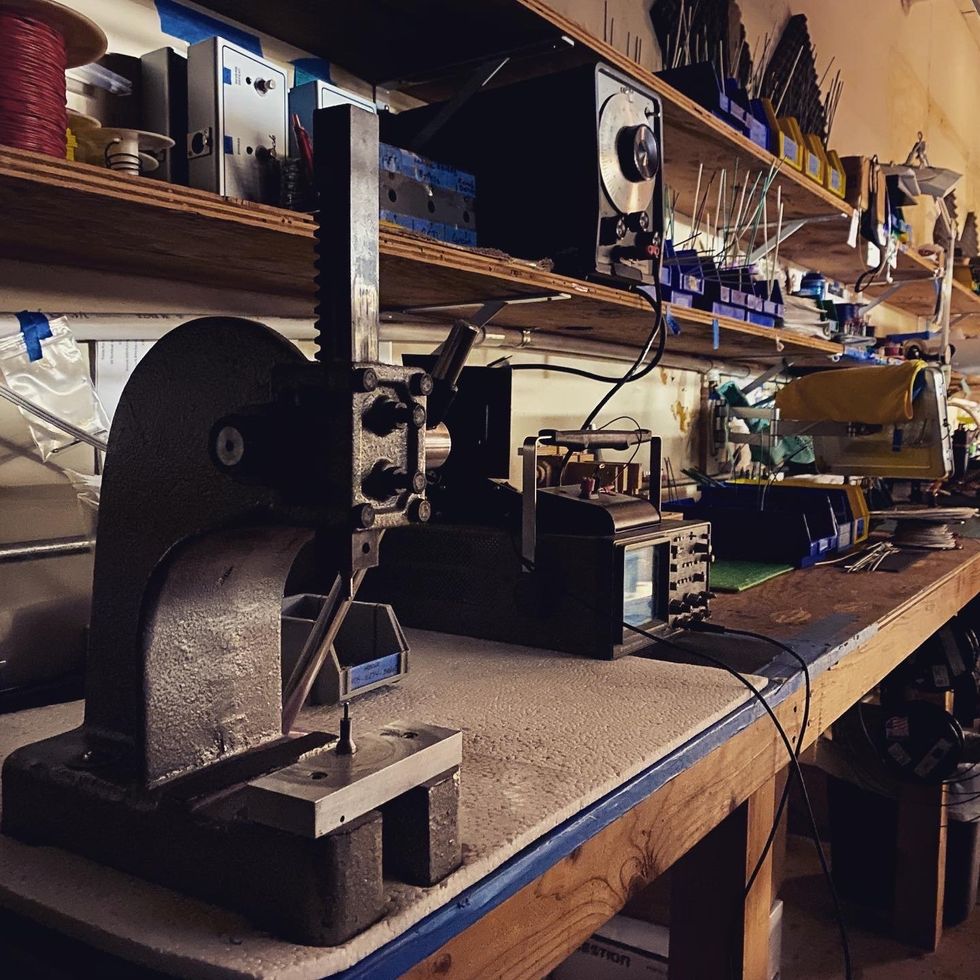

When Chris Mills started building his own electric guitars, he decided to build his own components for them, too. He suspected that in the course of the market’s natural thinning of the product herd, plenty of exciting options had been left unrealized. He started working with non-traditional components and winding in non-traditional ways, which turned him on to the idea that things could be done differently. “I learned early on that there are all kinds of sonic worlds out there to be discovered,” says Mills.

Eventually, he zeroed in on the particular sound of a 5-way-switch Stratocaster in positions two and four: Something glassy and clear, but fatter and more dimensional. In Mills’ practice, “dimensional” refers to the varying and sometimes simultaneous sound qualities attained from, say, a finger pad versus a fingernail. “I didn’t want just one thing,” says Mills. “I wanted multiple things happening at once.”

Mills wanted something that split the difference between a humbucker’s fullness and the Strat’s plucky verve, all in clean contexts. But he didn’t want an active pickup; he wanted a passive, drop-in solution to maximize appeal. To achieve the end tone, Mills wired his bobbins in parallel to create “interposed signal processing,” a key piece of his patented design. “I found that when I [signal processed] both of them, I got too much of one particular quality, and I wanted that dimensionality that comes with two qualities simultaneously, so that was essential,” explains Mills.

Mills loved the sound of alnico 5 blade magnets, so he worked with a 3D modeling engineer to design plastic bobbins that could accommodate both the blades and the number of turns of wire he desired. This got granular—a millimeter taller, a millimeter wider—until they came out exactly right. Then came the struggle of fitting them into a humbucker cover. Some key advice from experts helped Mills save on space to make the squeeze happen.

Mills’ ZUZUbuckers don’t have the traditional pole pieces and screws of most humbuckers, so he uses the screw holes on the cover as “portholes” looking in on a luxe abalone design. And his patented “curved-coil” pickups feature a unique winding method to mix up the tonal profile while maintaining presence across all frequencies.

“I learned early on that there are all kinds of sonic worlds out there to be discovered.” —Chris Mills

Mills has also patented a single-coil pickup with a curved coil, which he developed to get a different tonal quality by changing the relative location of the poles to one another and to the bridge. Within that design is another patented design feature: reducing the number of turns at the bass end of the coil. “Pretty much every pickup maker suggests that you lower the bass end [of the pickup] to compensate for the fact that it's louder than the treble end,” says Mills. “That'll work, but doing so alters the quality and clarity of the bass end. My innovation enables you to keep the bass end up high toward the strings.”

Even Mills’ drop-in pickups tend to look fairly distinct, but his more custom designs, like his curved-coil pickup, are downright baroque. Because his designs don’t rely on typical pickup construction, there aren’t the usual visual cues, like screws popping out of a humbucker cover, or pole pieces on a single-coil pickup. (Mills does preserve a whiff of these ideals with “portholes” on his pickup covers that reveal that pickup below.) Currently, he’s excited by the abalone-shell finish inserts he’s loading on top of his ZUZUbuckers, which peek through the aforementioned portholes.

“It all comes down to the challenge that we face in this industry of having something that’s original and distinctive, and also knowing that with every choice you make, you risk alienating those who prefer a more traditional and familiar look,” says Mills.

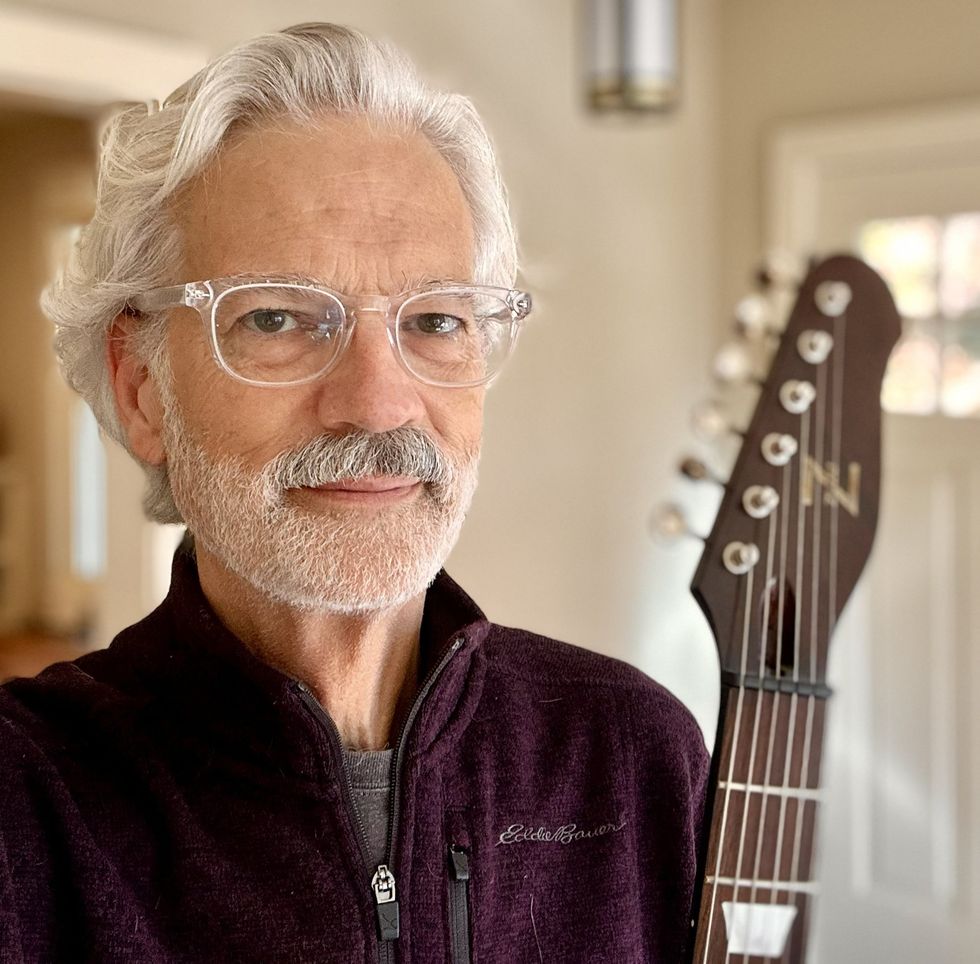

Pete Roe - Submarine Pickups

Roe’s stick-on Submarine pickups give individual strings their own miniature pickup, each with discrete, siloed signals that can be manipulated on their own. Ever wanted to have a fuzz only on the treble strings, or an echo applied just to the low-register strings? Submarine can achieve that.

Pete Roe says that at the start, his limited amount of knowledge about guitar pickups was a kind of superpower. If he had known how hard it would be to get to where he is now, he likely wouldn’t have started. He also would’ve worked in a totally different way. But hindsight is 20/20.

Roe was working in singer-songwriter territory and looking to add some bass to his sound. He didn’t want to go down the looping path, so he stuck with octave pedals, but even these weren’t satisfactory for him. He started winding his own basic pickups, using drills, spools of wire, and magnets he’d bought off the internet. Like most other builders, he wanted to make passive pickups—he played lots of acoustic guitar, and his experiences trying to find last-minute replacement batteries for most acoustic pickups left him scarred.

Roe started building a multiphonic pickup: a unit with multiple discrete “pickups” within one housing. In traditional pickups, the vibration from the strings is converted into a voltage in the 6-string-wide coils of wire within the pickup. In multiphonic pickups, there are individual coils beneath each string. That means they’re quite tiny—Roe likens each coil to the size of a Tylenol pill. “Because you’re making stuff small, it actually works better because it’s not picking up signals from adjacent strings,” says Roe. “If you’ve got it set up correctly, there’s very, very little crosstalk.”

With his Submarine Pickups, Roe began by creating the flagship Submarine: a quick-stick pickup designed to isolate and enhance the signals of two strings. The SubPro and SubSix expanded the concept to true hexaphonic capability. Each string has a designated coil, which on the SubPro combine into four separate switchable outputs; the SubSix counts six outputs. The pickups use two mini output jacks, with triple-band male connectors to carry three signals each. Explains Roe: “If you had a two-channel output setup, you could have E, A, and D strings going to one side, and G, B, and E to the other. Or you could have E and A going to one, the middle two strings muted, and the B and E going to a different channel.” Each output has a 3-position switch, which toggles between one of two channels, or mute.

“I’m just saying there’s some unexplored territory at the beginning of the signal chain. If you start looking inside your guitar, then it opens up a world of opportunities.” —Pete Roe

This all might seem a little overly complicated, but Roe sees it as a simplification. He says when most people think about their sound, they see its origin in the guitar as fixed, only manipulatable later in the chain via pedals, amp settings, or speaker decisions. “I’m not saying that’s wrong,” says Roe. “I’m just saying there’s some unexplored territory at the beginning of the signal chain. If you start looking inside your guitar, then it opens up a world of opportunities which may or may not be useful to you. Our customers tend to be the ones who are curious and looking for something new that they can’t achieve in a different way.

“If each string has its own channel, you can start to get some really surprising effects by using those six channels as a group,” continues Roe. “You could pan the strings across the stereo field, which as an effect is really powerful. You suddenly have this really wide, panoramic guitar sound. But then when you start applying familiar effects to the strings in isolation, you can end up with some really surprising textural sounds that you just can’t achieve in any other way. You can get some very different sounds if you’re applying these distortions to strings in isolation. You can get that kind of lead guitar sound that sort of cuts through everything, this really pure, monophonic sound. That sounds very different because what you don’t get is this thing called intermodulation distortion, which is the muddiness, essentially, that you get from playing chords that are more complex than roots and fifths with a load of distortion.” And despite the powerful hardware, the pickups don’t require any soldering or labor. Using a “nanosuction” technology similar to what geckos possess, the pickups simply adhere to the guitar’s body. Submarine’s manuals provide clear instruction on how to rig up the pickups.

“An analogy I like to use is: Say you’re remixing a track,” explains Roe. “If you get the stems, you can actually do a much better job, because you can dig inside and see how the thing is put together. Essentially, Submarine is doing that to guitars. It’s allowing guitarists and producers to look inside the instrument and rebuild it from its constituent parts in new and exciting ways.”