Perhaps it’s best if I start this article with a confession: I’m mostly known for being “the guy who built guitars for Sonic Youth.” Actually, I only built one guitar for one member of SY—Lee Ranaldo. Even so, I will probably live with this “stigma” for the rest of my life. Not that this worries me—it could be much worse. Here’s the story of how it happened.

(Be sure to check out the video of Dutch avant-garde luthier Yuri Landman delivering the DIY drone guitar he built for former Sonic Youth guitarist Thurston Moore. Bonus: see and hear Thurston demo this bad boy. Watch it all here.)

In 2006, I built a 12-string, zither-like instrument called the Moodswinger and donated it to Liars, an experimental band based in Los Angeles, as a form of mutual promotion. Full disclosure—this was a setup: I knew they had opened for Sonic Youth a few years before and that the connection might help me get my foot in the door with Lee and Thurston Moore. As soon as I finished that job, I contacted Sonic Youth’s management and offered them the same instrument deal. Within an hour I got a reply saying my request had been forwarded to Lee. The next day Lee enthusiastically replied that he was interested in such a project and proposed something like a harp guitar. The conversations with Lee eventually culminated in the 18-string Moonlander.

After that I did a third instrument called the Bachelor for Jad Fair of Maryland art-punk outfit Half Japanese—which meant I had my weird instruments in the hands of a fresh, hip young band, a famous veteran outfit, and a legendary cult act. They’re three of my favorite bands, for different reasons.

Left to right: The Moodswinger, Moonlander, and Bachelor.

Again, I stress that all three instruments were donations. I insisted on this, since I don’t possess the level of skills most expect from a bona fide luthier. I just have odd ideas and I’m not afraid to try them out. In order to both ensure that I didn’t get complaints and that I could maintain absolute autonomy in the builds, the first condition was not taking any money.

Regardless of this fact, media attention exploded almost immediately after all this happened. It first came from Pitchfork, then from basically every newspaper in my home country (the Netherlands), and then from the U.K.’s Guardian (which touted me as their “favorite luthier”—the latter being theirterm, not mine!). CNN then published an interview, which caused the whole media thing to spiral into a somewhat nervous situation for me: Bands starting asking me to build stuff—this time for money. But the strange reality was that nobody really played my instruments publicly! Liars did one track (“Leather Prowler,” on their album Liars), Blood Red Shoes did a couple of overdubs (“Colours Fade” and “When We Wake,” from Fire Like This), and the Luyas used it on three tracks (“Canary,” “Moodslayer,” and “Spherical Mattress,” on the album Too Beautiful to Work)—that’s probably the extent of it. My stuff and status was close to a big hoax.

Luckily, in 2009 I stumbled upon a suitable niche for my work—workshops and performances that revolve around my approach as a designer and musician. I dived underground and bid good riddance to the hysterical world of “indie pop,” where I really didn’t belong. I thrive in the world of research music, where there’s less media attention.

In 2012, Bart Hopkin and I published the guitar education book Nice Noise: Preparations and Modifications for Guitar, which soon prompted Premier Guitar to ask me to write an article about a crazy mod we ended up calling the Flying Double Dutchman Crunch. So I did: I trashed a cheap guitar and modded it in the rudest, fastest way possible. Predictably, the response was polarizing. Plenty of adventurous players were intrigued, but many others were livid that I would do such an evil thing. Personally, I think the guitar deserved it—it was a pretty bad Gibson copy in the first place.

Despite all the people up in arms about the Dutchman (me and the mutilated 6-string), I’ve been asked once again to walk the brave, courageous, and slightly crazy among you through another building project. But instead of damaging an existing guitar, this time I decided to do something to the best of my skills as a “luthier.” On top of that, I proposed to give it away to one of my favorite guitarists. Since I’ve already built something for Lee Ranaldo but not for Thurston Moore, I reached out to Thurston to see if he had any interest. He responded positively.

Both former Sonic Youth players are often credited for being exceptionally talented, but unlike many guitarists you’ll find on various best-guitarists-of-all-time lists, Lee and Thurston are not fast-playing virtuosos. They stand out from the crowd because of how they’ve worked out a wide range of extended techniques—banging their guitars with drum sticks, sticking screwdrivers under the strings to get strange sounds, strumming behind their Jazzmasters’ bridges, using radical alternate tunings, and doing whatever else they can think of to deconstruct traditional guitar playing. And they are capable of writing good songs with this “language.”

This new guitar I’ve built is based on many of those extended techniques, but even more specifically I hoped to achieve these four main goals on a single instrument:

Banjo-inspired drone strings. The 5th string on a bluegrass banjo starts at the 5th fret. So I figured, why not drill holes in the neck and add tuning pegs to the body—only our guitar will have four extra strings rather than just one! This allows you to play sets of drone-y open strings up to a certain fret position, and from there the extra strings go up the neck along with the normal strings. I’ve never seen a guitar with a mod like this.

More frets. I dislike that most guitars only have 21 or 22 frets (or 24 on some shred guitars). I understand frets get too narrow if you go beyond that, but I decided to add a few more frets that I think make particularly logical sense (while leaving out the in-between frets that are less likely to be used). These extra frets are on the body of the guitar, but they are not just “extra frets”: The added frets take the instrument into the microtonal, just-intonation realm used in a lot of non-Western music. In other words, the added frets will let the player access notes and harmonic intervals that are in-between the 12 notes typically heard in Western music.

Variable behind-the-bridge playing area. The Flying Double Dutchman Crunch guitar featured a behind-the-bridge playing area with an extra pickup behind the Tune-o-matic-style bridge and a new anchor point for all 6 strings at the butt end of the guitar. The scale length of the portion of the strings that extended from the Tune-o-matic to the new bridge/anchor was about a quarter of the guitar’s standard bridge-to-nut scale. I’m quite keen on this sort of setup, because it works excellent if you are hunting for dreamy, Sonic Youth-y overtone screams. Because of this, our new drone guitar features a similar behind-the-bridge playing area as well. However, here I’ve expanded the idea to include a metal bar that functions like a pivoting second bridge, altering the scale of the behind-the-bridge playing area so you can create a sky full of sparkling overtones at various positions.

Djent bars (sort of). Last year I performed at the Resonate music, visual-arts, and digital-culture festival in Belgrade, Serbia. During my soundcheck I met the experimental noise duo Senyawa from Indonesia. The “guitarist,” Wukir Suryadi, plays an incredible tube-shaped stringed instrument that he made from a piece of bamboo. Before he joined vocalist Rully Shabara to create Senyawa’s fascinating blend of folk, punk, and neo-tribal music, Wukir played the same instrument in metal bands. In addition to its strings, the bamboo guitar has three thin slices of steel that are mounted quite floppy on the instrument. When he dials in the parameters of his amp, he searches for an EQ setting that resonates with the pieces of steel and achieves the typical scooped-distortion djent sound of metal music. Instead of palm-muting his low E, he strums the metal bars to get a similar result. What a wonderful, efficient, and smart invention! I tried to copy that idea on this guitar by mounting three metal pieces (which have their own 1/4" output) above the low E string.

Okay, enough background info. The only other thing I’m going to point out before we begin is that all my measurements for materials, drill-bit sizes, etc. are in the metric units that we use here in Europe (and much of the rest of the world). For other readers, we’ve converted measurements to the simplest decimal equivalent in inches, but you may need to adjust some slightly to accommodate materials at your disposal.

All right—let’s dive in!

Stuff You'll Need

Guitar Parts and Raw Materials- One 25 1/2"-scale, Strat-style aftermarket neck

- Standard Strat-style neck plate

- One set of six-on-a-side (Strat-configuration) tuners

- Four open-gear acoustic tuners

- One 3'-long piece of .7"- thick (18 mm) meranti furniture paneling (real wood glued in rows of 2")

- One 2.4" x 4" (6 cm x 10 cm) piece of .27"-thick (7 mm) meranti board (or fretboard blanks of same size)

- One standard 10" x 16" pickguard blank

- 23.5" (60 cm) stainless-steel rod

- One 10" (25 cm) piece of .4” x .4" (10 mm x10 mm) brass

- One 10" (25 cm) piece of .08" x .4" (2 mm x 10 mm) brass

- One 6" (15 cm) piece of .08" x. 6" (2 mm x15 mm) brass

- One 6" (15 cm) piece of .08" x 1.2" (2 mm x 30 mm) brass (for the outputs)

- One 3'-long piece of round .04" (1 mm) spring steel

- One Duesenberg 12-string bridge (available from rockinger.com, product no. 3643N)

- Spool of preferred fretwire weight

- Full set of multi-colored acrylic paint OR colored dot stickers (for marking harmonic fretboard positions)

- Small can of brush-able or aerosol-spray acrylic varnish (for the body)

- Two strap buttons

- Three high-quality, Strat-style pickups (preferably with alnico magnets)

- Box of steel Phillips-head wood screws in sizes ranging from .4" to 1.4" (10 mm to 35 mm) in length

- 20 mm M6 headless Allen bolt

- Three 1/4" mono outputs

- One 250k volume pot

Tools

- Standard Phillips-head screwdriver

- One sheet of 60-grit sandpaper

- Belt sander with 60-grit sandpaper

- Drill press

- 2 mm / .08" drill bit (for new string holes)

- 3.5 mm / .14" drill bit (for screw holes)

- 5 mm / .2" drill bit (for bridge-post holes)

- 6.5 mm / .26" drill bit (for tuning-peg holes)

- 7 mm / .28" drill bit (for volume-pot hole)

- 9 mm / .35" drill bit (for 1/4"-output holes)

- 10 mm / .39" drill bit (for leg-rest and upright-stand steel bars)

- Electric screwdriver/drill

- Brush

- Wood saw or hacksaw

- Angle grinder

- Fret-slotting saw

- Nut-slotting files

- Standard adjustable wrench

- Wood glue

- One container of wood filler (just in case)

- Soldering iron

- Rosin-core solder

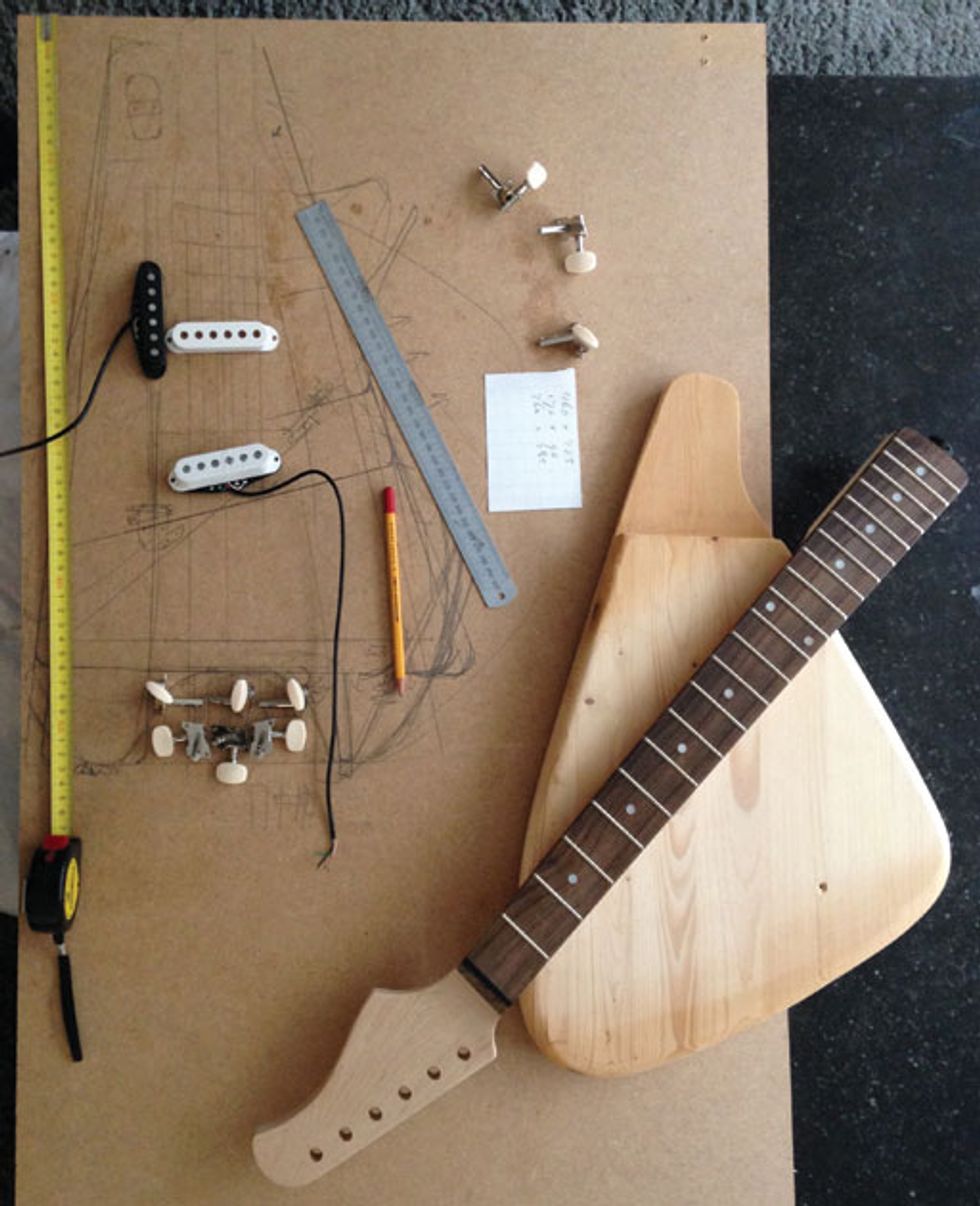

Photo 1 — The raw materials for our drone-guitar body: three pieces of .7" store-bought solid wood that we will

later glue together.

The Build

I’m not sure if every country has this, but in the Netherlands we have ready-made wooden plates called “furniture paneling” (Photo 1), and they come standard in 18 mm (0.7") sheets. I find them very handy, since you can simply glue two of them together for a perfect guitar-body thickness. The ones I bought are made of Shorea, a southeast Asian wood sometimes sold under the name “meranti” or “Philippine mahogany.”

Photo 2 — As I sketched out plans, I realized there wouldn’t be enough space to fit my four main design goals onto my previous favorite body style, a rough blank of which is shown here under our aftermarket neck.

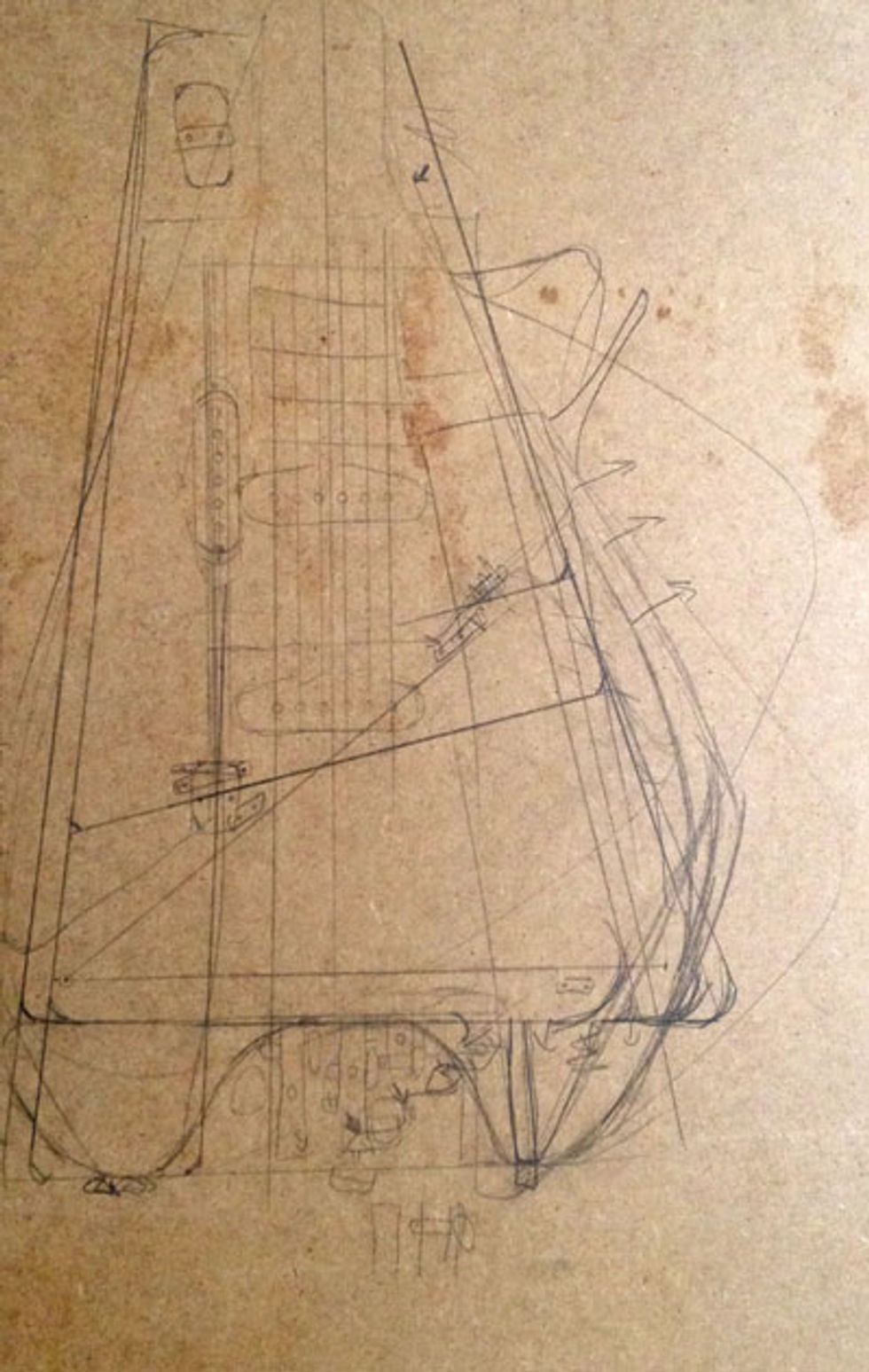

I used to make guitars with a rather uncommon body shape (Photo 2)—a hybrid of two of my favorite guitars: the Vox Mark VI “Teardrop” and the Fender Jaguar. My design was kind of like a Mark VI with an offset waist.

Photo 3 — I like to think of the shape as a cross between a Vox Mark VI and a Fender Jag.

During sketching for this project, I quickly found that my four previously mentioned goals wouldn’t work within that body contour, so I decided to go for a shape that’s more like a cross between Gibson’s Flying V and Explorer body styles (Photo 3).

Photo 4 — The main body parts are cut and laid out to double-check overall fit.

After sketching for half an hour to arrive at the final shape and positioning for the various pieces and components, I cut the wooden panels according to the sketch and then laid the pieces out with our aftermarket neck to see if it looked good and still seemed like it would accommodate all our design goals (Photo 4).

Photo 5 — Pickup cavities have now been routed, and the edges of the body pieces have been smoothed out for more comfortable playing.

Next, I routed holes for the pickups in the top body piece, smoothed out some rough edges on all the shapes, glued the body pieces together, and then smoothed and polished things again so it felt and looked nice (Photo 5).

Photo 6 — I originally hoped to add 5 banjo-inspired strings, but as I drilled holes to rout the new strings through the 7th and 12th fret positions I realized there was no way to safely execute the hole at the middle of the 12th fret without damaging the neck’s truss rod. I later used standard wood filler to patch that hole.

After that I drilled holes in the neck for our four extra, banjo-inspired strings (Photo 6). Actually, I initially planned to add five extra strings by drilling holes between the six standard strings at a couple of different fret locations. I thought it might be possible to angle the middle hole a bit to avoid hitting the truss rod, but unfortunately this turned out to be impossible to accomplish, so I ended up filling that hole later.

Also, because I couldn’t decide which fret positions would work best while playing—this is uncharted territory, after all!—I decided to drill two holes behind the 7th fret for the low strings, and two holes behind the 12th fret for the high strings. Admittedly, there’s not a lot of logic about this choice, since only the final result will reveal whether it worked or not. On the bright side, it’s rather easy to fill holes and add more at desired positions if I wish. This is an experimental instrument, so we need not be afraid of taking chances!

Photo 7 — With wiring holes now drilled for all three pickups, we can now install our 12-string bridge.

The next step was to attach our aftermarket neck and locate where to install the bridge—which is a 12-string Duesenberg model. Since our neck is intended for a 65 cm- / 25.5"-scale instrument, I carefully measured 25.5" from the nut to the body, marked the spots for the two bridge posts, drilled holes for the anchors, and began installing the bridge (Photo 7).

Photo 8 — Measuring and marking locations for five extra pieces of fretwire to be installed in an extra fretboard that will be mounted to the thin, pickguard-like piece of wood (shown here in rough, yet-to-be-shaped form with four guide holes for two perpendicularly mounted single-coil pickups).

Remember how my second goal (after adding the banjo-y drone strings) was to add extra frets to the body? That’s what I worked on next. The extra fretboard—which is simply a piece of .27"-thick (0.7 mm) 2.4" x 4" (6 cm x 10 cm) meranti—will sit atop a thin, almost-rectangular piece of wood that’s attached to the top body piece like a pickguard—except that A) we couldn’t care less about scratching the body of this delightful abomination, and B) it’s really only functioning as a base for the extended-range frets and as an anchor point for two of our three single-coil pickups (Photo 8). The faux-pickguard/pickup plate is made from a 5.7" x 4.7" (14.5 cm x 12 cm) piece of the same .27"-thick meranti, although you may opt to fashion yours out of a standard 10" x 16" pickguard blank.

For a 65 cm- / 25.5"-scale guitar, the first octave is, of course, at the 12th fret (approximately 32.5 cm or 12.8" from the bridge), while the second octave is 16.25 cm / 6.4" from the bridge. Once I determined where I’d attach our faux-pickguard/fretboard base, as well as where the new fretboard will attach to the base, I drew a line on the second fretboard at the 16.25 cm / 6.4" second-octave mark. I also added a line at the third octave, which is 8.1 cm / 3.2" from the bridge. I also drew marks for a minor third at 13.8 cm / 5.4" from the bridge, a perfect fourth at 12.3 cm / 4.8", and a so-called harmonic seventh. The harmonic seventh is not part of the 12-tone scale, but you can hear it when you pluck a harmonic between the 2nd and 3rd frets on the guitar neck. A harmonic seventh can be heard at 1/7 of the scale length, as well as at five other spots on the strings—2/7, 3/7, 4/7, 5/7, and 6/7 of the total scale length. The one I drew is the one closest to the bridge (the 6/7-scale one), which is about 9.3 cm / 3.6" from the bridge.

[Left to right] Photo 9 — Our extra fretboard after I used a fret saw to cut five new fret slots. Photo 10 — The extra fretboard after pounding in the new frets. Photo 11 — The new frets after beveling with a belt sander.

From there I secured our new fretboard blank with a set of clamps so I could use a fret saw to carefully carve out channels for our new fretwire (Photo 9). I then hammered them in (Photo 10) and sanded off the frets with my belt sander until they looked smooth enough to play comfortably (Photo 11).

Next I installed the drone guitar’s electronics. Naturally, the instrument’s unusual pickup arrangement could lead to an equally unusual control setup. However, I never work with complicated circuits, tone knobs, or switching like you’ll see on Fender, Gibson, or other mass-produced guitars. I once read that the guys in Sonic Youth used to strip out as much of their guitars’ electronics as possible in order to keep the signal fresh. That’s basically what I do, too, so our wiring is pretty simple: I installed three separate 1/4"outputs—one for each single-coil, and a single volume knob that only affects the main pickup in the standard body location. That’s right, there are no controls whatsoever for the pickups located behind the bridge and under the steel bars—they go straight to the output. I prefer separating the pickups’ outputs and combining them with an outboard mixer, and I use a tuner pedal’s muting function to switch additional nonstandard pickups like the ones on the drone guitar in and out of the mix. This enables me to dial in the exact amount of desired extra sound coming from different regions on the guitar. However, you could just as easily equip a similar instrument with a single output, individual volume knobs for each pickup, and either a master tone or tone knobs for each pickup.

Photo 12 — Using three clamps to glue the extra fretboard to the wired-up and installed pickup plate.

After installing the electronics, I again used a set of clamps to glue the new fretboard to the pickup plate (Photo 12). After doing so, I realized that I needed to sand the pickup plate a bit thinner in order to get the action of these frets correct.

Photo 13 — Inspired by an instrument played by Wukir Suryadi in the Indonesian experimental duo Senyawa, I used brass tailpieces to mount three pieces of resonant spring steel above the standard playing area.

Next I worked on the djent-bars portion of the build inspired by Senyawa instrumentalist Wukir Suryadi’s bamboo “guitar.” I used an angle grinder to cut three .04" (1 mm) pieces of spring steel and mounted them to the body in a spot that felt easiest to access from a typical guitarist’s right-hand playing position. I again used the angle grinder to cut two 1.5" long (4 cm) pieces of brass—one that’s .4" x .4" (10 mm x 10 mm) and one that’s .08" x .4" (2 mm x 10 mm)—and then used four screws to mount the rods (Photo 13). I prefer brass because it’s strong, isn’t difficult to work with cleanly, and you can make screws thread in it (unlike aluminum, which is too soft). Steel is both harder to work with and prone to rust.

As I described earlier, my plan was to copy Wukir’s invention, but once I mounted the pieces I noticed the sound of the rods was more resonant—almost like hitting a metal fence. After some experimentation I found that the rods would need to be muted with foam in order to get the Senyawa sound. However, I found the “fence” sound just as interesting, so I decided to leave it as is. If Thurston decides he’d like to get a sound more like Wukir’s steel strips, I’ll advise him to prepare the steel with a piece of foam.

Photo 14 — Intonating our drone guitar’s nine strings.

After working on the steel rods, I moved on to stringing the instrument and setting intonation (Photo 14). Even though our modded guitar is only set up to accommodate 10 strings, I used a 12-string bridge because it allows me to easily vary string spacing at the bridge. Also, you’ll notice in the photo of the finished instrument (Photo 17) that I initially only installed nine strings instead of 10. I didn’t use the standard 5th-string tuner because I felt it would be easier for me to play that way. My choice of tuning was (from bass bout to treble bout): low E, mid E, low A, mid A, low E, high E, followed by all four top strings (two anchored at the headstock, and two extending from the new holes at the 12th fret) tuned to high E. In other words, when you press the 12th fret all four thin strings are the same pitch. Of course, there’s a good chance Thurston will add the 10th string or opt for a completely different stringing approach—that’s up to him. There are no rules for this instrument!

You’ll probably also notice that I abandoned the holes at the 7th fret and drilled extra holes in the headstock near the standard 6th- and 7th-string locations. Why? Unlike the thinner strings that begin at the 12th fret—which work very nicely and yield a dreamy, mandolin-like drone—I found the result with low strings starting at the 7th fret too impractical—a nasty, rumbly, out-of-tune situation that didn’t work with my playing skills.

As you can see, I drew three lines on the extra fretboard, but didn’t add frets in those locations. However, I did apply lacquer over the penciled-in lines to prevent them from fading. These lines represent harmonic positions. In the picture of the finished guitar you’ll also see a series of color-coded dots at different positions along the neck and extra fretboard. I use this system on my Moodswinger and Home Swinger instruments to indicate a harmonic series. A gray dot (which isn’t used on this drone guitar) indicates half of the string length, red indicates a third of the string length, orange indicates a quarter, yellow is a fifth, green is a sixth, aqua is a seventh, blue is an eighth, and purple is a ninth. Most frets on the extra fretboard correspond with the harmonic positions, except the ones on either side of the yellow dot. There’s no particular reason for this except that I often play melodies that involve the open strings in combination with the minor third and perfect fourth (frets 3 and 5 on the neck), so I included the 27th and 29th fret instead of the 28th fret that overlaps with the yellow dotted line.

Helpful hint: The harmonics available at these positions are much easier to get when you’re playing with heavy distortion rather than a clean signal. A loud, dirty tone should enable you to access a second octave at the orange dot, a minor third at the 2nd fret of the extra fretboard, a major third at the yellow dot, a perfect fourth at the 3rd extra fret, a perfect fifth at the green dot, a harmonic seventh at the aqua dot, a third octave at the blue dot, and a major second at the purple dot. (If you are a math geek, I recommend reading Genesis of a Music by microtonal composer Harry Partch. Its 400 nightmarish pages about math and musical harmony explain all of what I just described. If you are a soft science person, forget this info as soon as possible and just strum the strings and make music!)

Photo 15 — Here I used a couple of spoons to help me determine the proper angle for two pieces of brass that will keep our pivoting, behind-the-bridge metal bar high enough to function as a second bridge.

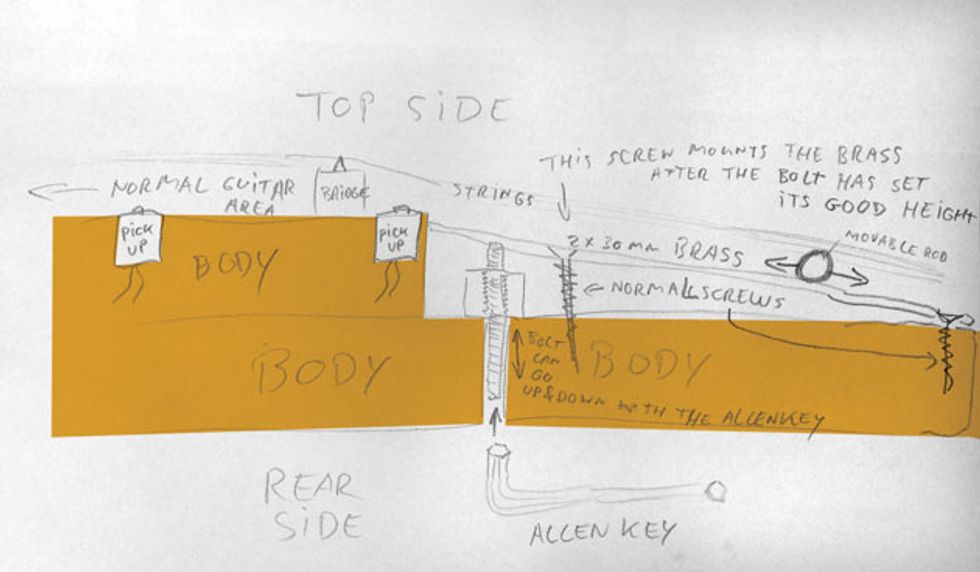

Next up in this demented project is the movable rod that alters the scale of the behind-the-bridge playing area. To make this work correctly, I had to figure out a way to push it up a bit and make it function like a slide or a second, adjustable bridge. Spoons were handy tools in determining the proper angle: I propped one end of two raw brass blanks up with the spoons, then moved them around to determine the best angle and height for the bar (Photo 15). I thought I would need two brass guides, one on both sides of the strings, but after I installed the first one on the bass side I found that it worked just fine by itself. To hold the brass guide in place, I secured two pieces of brass that I fashioned with the angle grinder—a small one measuring 1.5" x .4" x .4" (4 cm x 10 mm x 10 mm) and a thinner, longer one measuring 4.3" x .08" x .6" (11 cm x 2 mm x 15 mm)—in a T-like arrangement using four wood screws: one at the tail end that’s .6" long (15 mm) and three others that are .8" long (20 mm). See Diagram 1.

Diagram 1

On the bass side of the instrument, I secured the movable rod/bridge with a 1.4" (35 mm) wood screw and two metal washers to help achieve the proper height (Photo 16). Although you can’t tell from the photos, if you look again at Diagram 1 you’ll see that, underneath the portion of the two bars that’s closest to the bridge, there’s an M6-sized headless Allen bolt threaded through the bottom piece of brass. This setup allows me to alter the tension of the rod/bridge against the strings by adjusting both the Allen bolt and the brass-bar screw on the top of the guitar (the one nearest to the Allen bolt) in tandem with each other.

Photo 16 — After installing the first brass height “ramp” and attaching the bar at its pivot point, I realized that the second brass height ramp wasn’t necessary. Here you can see the tuner-protecting rod that also functions as a built-in stand, and the instrument’s control panel: a volume for the main pickup, and a 1/4" output for each single-coil pickup. The left output is for the steel bars’ pickup, the middle one is for the behind-the-bridge pickup, and the right output is for the main pickup.

Okay, let’s talk about the tailpiece I created at the butt end of the guitar. If you look closely, you’ll see that it’s a pretty handy string-mounting system. I used the angle grinder to cut two pieces of brass that sandwich the strings. The thicker base piece is 4" x .4" x .4" (10 cm x 10mm x 10mm). The thinner top piece is 4" x .08" x .4" (10 cm x 2 mm x 10 mm) and it screws to the guitar’s top using .8" (20 mm) wood screws. Between the two brass pieces are three M3-sized nuts that I drilled out a bit and use, basically, as washers, because standard washers aren’t thick enough and are too wide. The M3 nuts create space for the strings to fit between the brass pieces, as well as help keep their ball ends in place. I developed this system on my early Springtime guitars, and what I love about it is that it allows me to tweak string spacing. A series of holes would also work, but I think this is more flexible.

Photo 17 — The finished drone guitar.

After completing some minor touches that I’m sure you can figure out on your own (like adding strap buttons), I was pretty much done with the drone guitar. As you can see from Photos 16 and 17, I also added two steel rods that I cut with the angle grinder: one protects the rear tuning pegs and enables the guitar to stand up when placed against a wall or amp, and the other enables the guitar to rest on your leg so you can play more comfortably while sitting. I secured them by first drilling holes to the desired depth in the body, then drilling a 3.5 mm / .14" hole near one end of each rod; then driving a screw from the exterior through the hole and into the wood on the other side of the rod.

First Playing Impressions

So how do I feel about my first try at this crazy amalgam of ideas? Perhaps Thurston is the best one to ask. The extra holes in the fretboard obviously open new possibilities by accommodating new strings, but, of course, they also limit some of your fingering options in the same vicinity. The instrument was designed largely to open up lots of drone possibilities, but even for the average adventurous player it will probably only be feasible for one or two songs rather than for a complete repertoire—but the same can be said for the hordes of alternate-tuning guitars used by Thurston Moore and Lee Ranaldo. I’ll admit that the holes in the bass side of the neck didn’t work for me—although they might for Thurston and other players. I found the ones on the treble side more to my liking, with the holes near the 12th fret offering more playing freedom than the ones at the 7th fret.

Also, the Senyawa-inspired steel rods ended up sounding different from how I’d envisioned them. However, I liked the steel “fence” sound so much I didn’t mute the rods. As for the extra fretboard, to me it’s killer. Guitarists who prefer neck-pickup sounds will have to adjust to the fact that the extra fretboard must be located where a neck pickup would normally be, but I always play the bridge pickup anyway so the adjustment was no problem for me. It works perfectly for the way I play, and I’m certain it will appear on many of my future guitars.

The slider behind the bridge is great, too. I love having an onboard stick available at all times, instead of having to grab a drumstick or screwdriver. The disadvantage is that I had to abandon my plan for a vibrato arm. It would be nice to have both, so perhaps in a future design I’ll figure out how to combine both elements.

Thanks, PG and Thurston, for letting me try out this project!