Initially conceived as the British answer to the American-made Maestro Fuzz-Tone (built by a subsidiary of Gibson), the Tone Bender—and its somewhat confusing iterative evolutions over the years—went on to carve out its own definitive place in history. Its rank in the sonic pantheon in the sky is assured by its use on seminal recordings by a plethora of legendary guitarists from the British scene in the mid-to-late 1960s. Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Mick Ronson, and Pete Townshend were among the many users who deployed the Tone Bender to devastating aural effect.

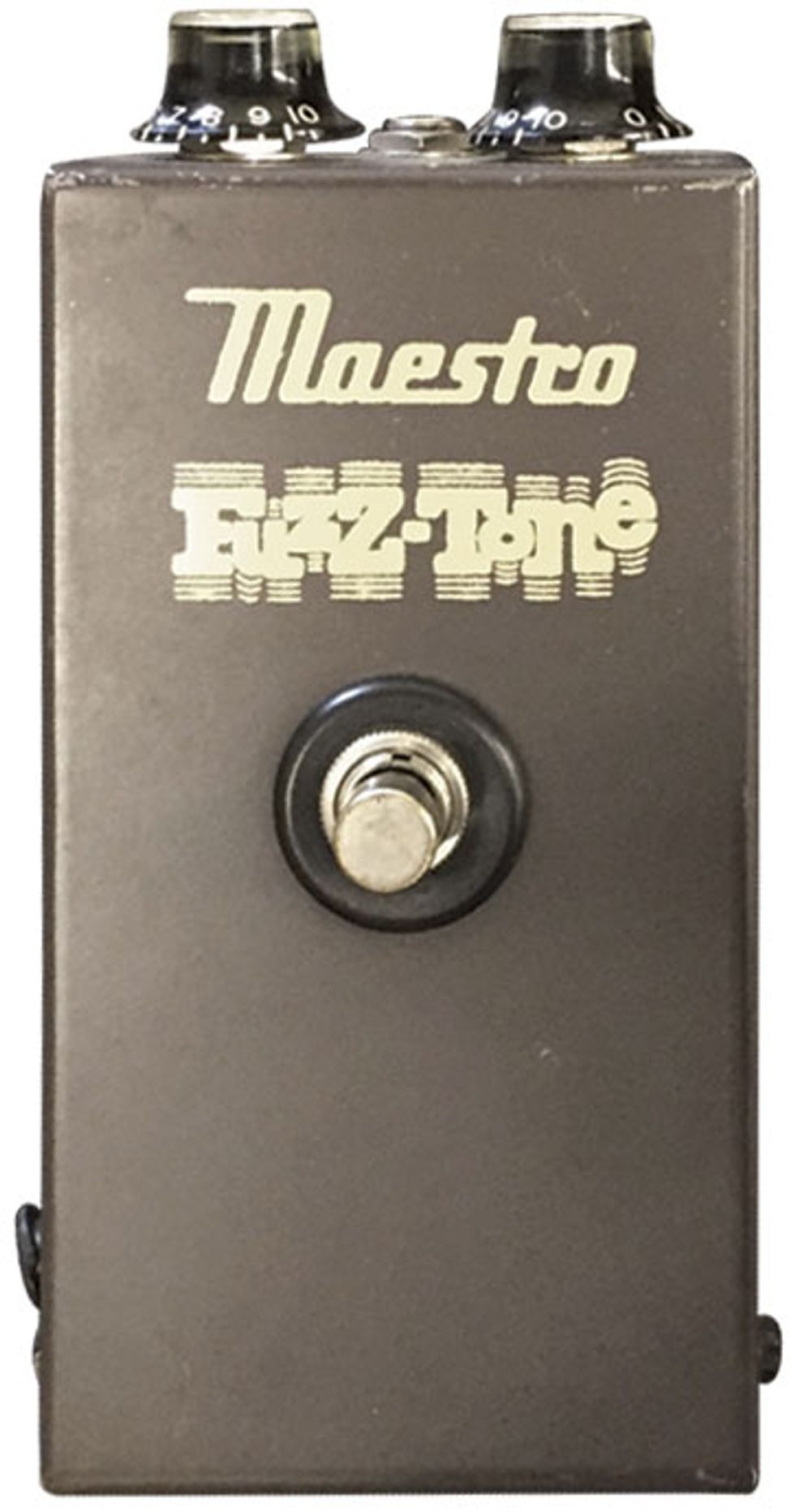

The popularity of the U.S.-made Maestro FZ-1—and its scarcity in the U.K.—were leading impetuses for the design of the Tone Bender. Photo courtesy of Tim's Gear Depot

To be sure, the Tone Bender has a convoluted, murky history. But while it went through many changes during its time, each version had something to offer to eager guitarists who were ready to kneel at its altar of fuzzy brilliance. A host of differing companies and individuals all played a part in bringing its thunderous tones to fruition, so let’s make our way through the haze of history and attempt to find some clarity on the story behind this titan of tone.

In the Beginning…

Electronics engineer Gary Stewart Hurst, a former Vox employee, designed the first iteration of the Tone Bender MkI in 1965. Heavily inspired by the Gibson-built Maestro FZ-1 Fuzz-Tone, which was hard to obtain in England at the time, Hurst produced a 3-transistor circuit after being asked by session musician Vic Flick for a pedal that would emulate the sound of the FZ-1 but with more sustain. (Flick, an in-demand session player of the era, is now most famous for playing the iconic James Bond riff.)

A critical Maestro design element that Hurst changed was the use of 9V power. Although this is now standard in virtually all guitar pedals, the few pedals that existed in 1965 were powered by 1.5V or 3V. This voltage boost, along with a few resistor-value tweaks, allowed the MkI—which features level and attack knobs, much like the Maestro’s volume and attack controls—to be louder and achieve greater sustain than the FZ-1.

A raspy yet articulate fuzz with laser beam focus, the MkI offered guitarists the ability to coax the gritty, distorted sounds that were coming into vogue without having to resort to Kinks guitarist Dave Davies’ method of taking a razor blade to his amp speakers for more breakup.

A classic early example of the MkI in action can be found on the 1965 Yardbirds’ single “Heart Full of Soul.” The story of how this came about is rather interesting, too: Originally a tabla and a sitar player had been booked to play on the song, but they purportedly had trouble with the 4/4 time signature, prompting Jeff Beck to use a MkI in his attempt to give the riff a more Eastern sound.

Early versions of the MkI were built by Hurst (in wooden enclosures) and sold by Macari’s Musical Exchange, a music store on Denmark Street in London. Hurst built approximately 100 MkI Tone Benders in the wooden enclosures before changing to a wedge-shaped, folded-steel enclosure with a gold-and-black finish.

Around the time of the introduction of these steel enclosures in mid-to-late 1965, the pedal began being marketed under the Sola Sound name—a brand created by brothers Joe and Larry Macari in late 1964.

Tone Benders were then sold both through Macari’s stores around the U.K. Starting with fuzzes and other effect pedals, the Macari’s later expanded into a range of musical products including amplifiers, mixers, spring reverbs, and microphones under the Colorsound brand, which they also started.

A leading proponent of the MkI was David Bowie sideman Mick Ronson. Frequently pairing it with a wah set to different fixed positions, Ronson used the Bender to push his sound through the sonic stratosphere on songs like “Moonage Daydream” off The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.

The MkI.5 was sold under both the Sola Sound and Vox monikers. Here we have a 1967 specimen of the latter in a sandcast-aluminum enclosure. Photo courtesy of Jimmy Behan/SuperElectricEffects.com

The Tone Bender MkI.5

In early 1966, the Tone Bender went through the first of its many circuit changes. Reportedly looking for a cheaper, easier-to-produce design, Sola Sound equipped the Mk1.5 with two transistors (rather than three) and morphed the enclosures from the wedge style to a sleeker sandcast-aluminum design.

Tonally speaking, the MkI.5 has a different feel and response than its predecessor. Less saturated and with more low end, it’s a more controllable, less gnarly fuzz than the MkI.

The MkII, famously used by Jimmy Page during his Yardbirds and early Zep years, became so popular that Sola Sound agreed to build it under other monikers for such companies as Marshall, Vox, and Rotosound.

Photo courtesy of Stuart Castledine

The Tone Bender MkII

Only a few months after the MkI.5 arrived on the fuzz scene, the MkII was born. Arguably the most famous Tone Bender, the MkII reverted back to its original 3-transistor spec to yield a complex, harmonically rich tone with plenty of saturated, soaring gain. Like its forebears, the MkII features the dual level-and-attack control setup, and uses germanium transistors for its distinctive tone—usually OC75 transistors, though a few extant examples feature OC81Ds.

As the MkII increased in popularity, Sola Sound manufactured it in various guises for companies such as Marshall, Rotosound, and Vox—although the latter eventually took over production of their own version, which was built at JEN in Italy.

Perhaps the most well known MkII user is Jimmy Page, who used one during his tenure on guitar with the Yardbirds and in the early Led Zeppelin years. The first Zeppelin album is particularly laden with examples of thunderous MkII tone. Paired with a Telecaster and Supro amp, the Tone Bender’s classic, throaty midrange response can be heard on tracks such as “Dazed and Confused,” “You Shook Me,” and “How Many More Times.”

In addition, Donovan’s psychedelic ode, “Hurdy Gurdy Man,” features a fine example of white-hot MkII tone. Guitarist Alan Parker—not Jimmy Page, as widely thought—played the slippery solo with a Gibson SG and a MKII routed through a Fender Deluxe Reverb.

Although early Marshall Supa Fuzzes were identical to Sola Sound MkIIs, when Marshall later assumed manufacturing responsibility for the pedal, it was slightly modded for more low end. It also ended up with an inexplicable “filter” label for its attack control. Photo courtesy of Noise Floor

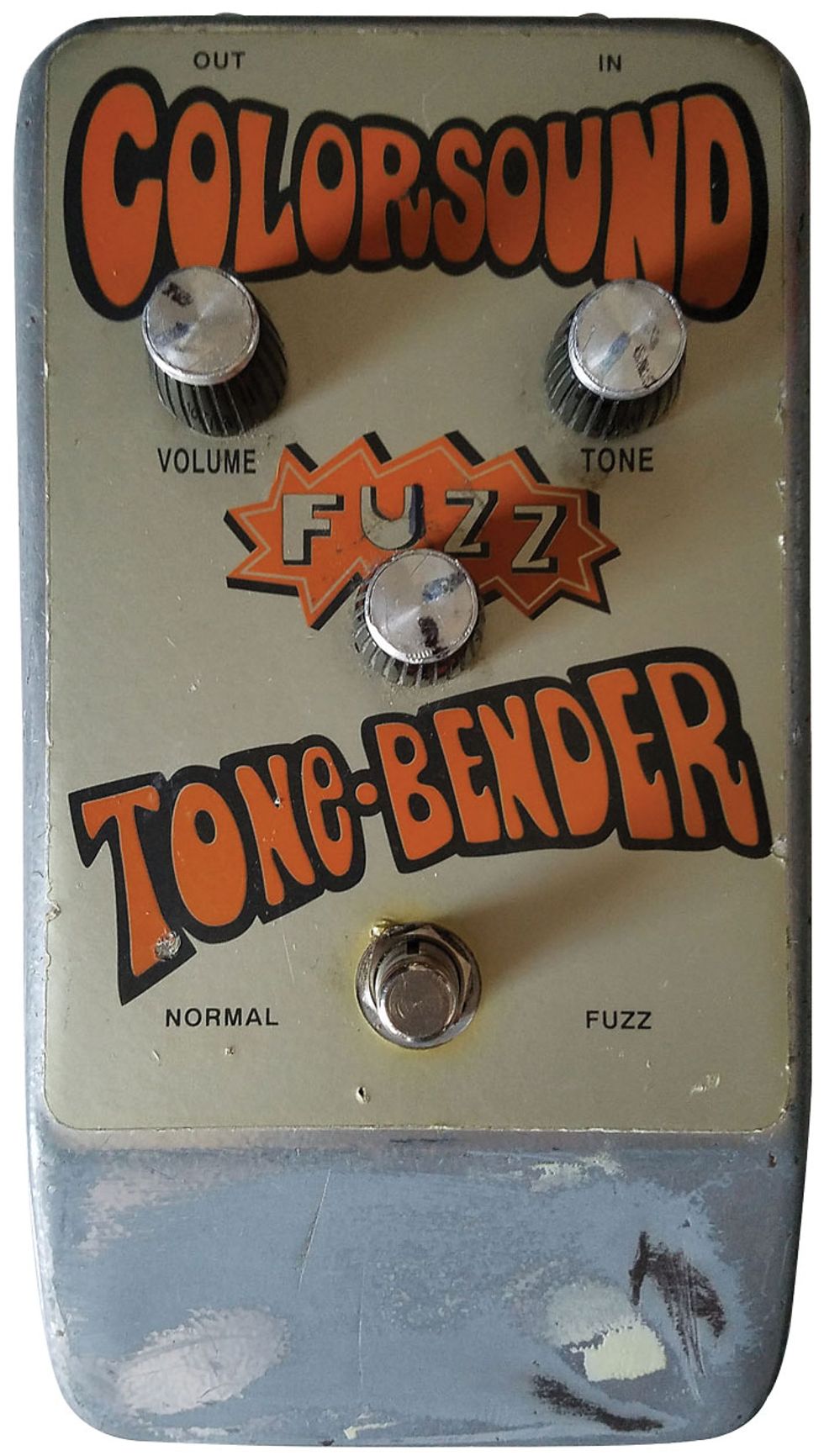

The Marshall Supa Fuzz

Initially made for Marshall by Sola Sound, the Marshall Supa Fuzz was essentially a Tone Bender MkII, as it had identical specs to the Sola Sound version. The longest-running production version of the MkII circuit, the Supa Fuzz was made from 1966 to the early ’70s. However, Marshall eventually took over manufacture of the pedal and modified the circuit for a touch more bass response. Confusingly, the Supa Fuzz’s attack control was mislabeled “filter” due to the fact that a different circuit design—a MkI variation in which the filter knob was a basic tone control—was initially intended to be used. Favored by Justin Hayward of the Moody Blues for its full, singing sustain, the Supa Fuzz also appeared at the feet of Pete Townshend in live shows between 1967 and ’68.

MkIII (including this Rotosound-branded specimen from 1969) and MkIV Tone Benders were overhauled to include a new treble control that yielded tones similar to the Burns Buzzaround. Photo courtesy of Chris Nelson

The Tone Bender MkIII & MkIV

In 1968, the Tone Bender went through another sonic makeover. However, rather than just losing or adding a transistor, this time the circuit was totally revamped—including with a new “treble” control. The result was a more mid-focused tone and a wider range of fuzz ferocity. The MkIII sound is so different, in fact, that it’s actually more similar in tonal characteristics to the Burns Buzzaround—a lesser-known fuzz produced in small numbers by the Baldwin Burns company in England. (At the time, the Buzzaround was King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp’s fuzz of choice.)

Jimmy Page was spotted deploying a Rotosound MkIII at the filming of the French TV show, Tous En Scène. Further, it is thought that Page used the Rotosound MkIII for some of the songs on Zep’s BBC Sessions double album. “The Girl I Love She Got Long Black Wavy Hair” certainly has the midrange bark characteristic of a MkIII.

A later MkIV Tone Bender featured largely cosmetic changes in the form of different graphics and enclosure style. Production of that version continued until 1976.

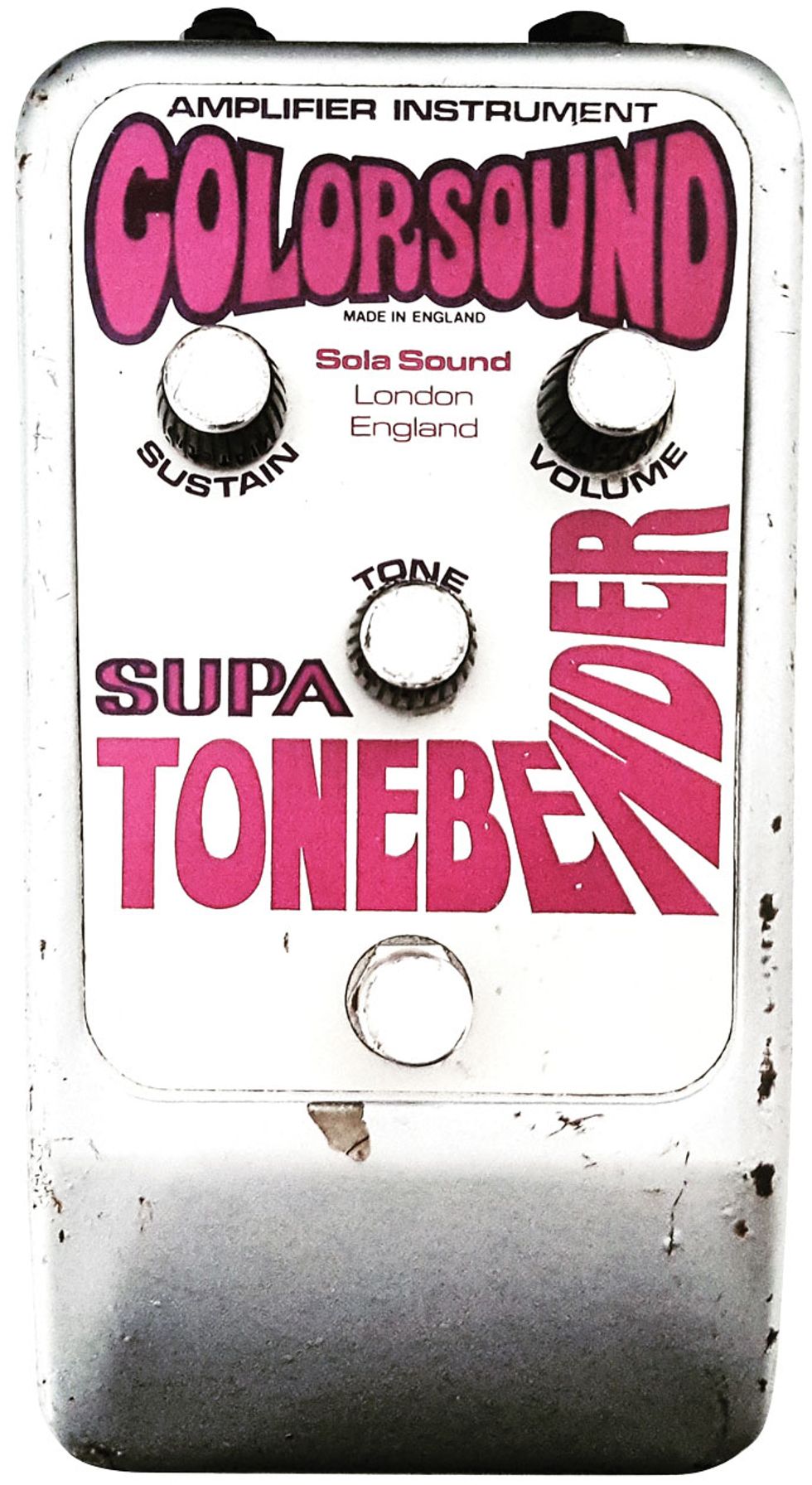

A notable user of the colorfully housed Supa Tone Bender was Steve Hackett during his tenure with Genesis. He also used a Marshall Supa Fuzz. He mounted the Supa on an early custom pedalboard. Photo courtesy of PedalPawn.com

The Supa Tone Bender

Released in 1973 under the Colorsound brand, the Supa Tone Bender had a noticeably different tone and feel to the previous pedals in the series. This was due to the fact that it didn’t use germanium transistors like previous Tone Benders, and was essentially a mildly modified Big Muff—complete with four silicon transistors and diode clipping. Based on the “ram’s head” Muff of the same period, the Supa removed two of the clipping diodes from the popular Electro-Harmonix circuit and added an extra capacitor, resulting in increased output volume compared to the Muff. Supa Tone Benders also differed in that they were housed in a wider, much more colorful enclosure.

Sonically, the Supa Tone Bender was far removed from its germanium-driven ancestors. Less harmonically intricate, its signature sound is a hefty, woolly fatness, with thundering low end and scooped midrange. Later versions of the Supa Tone Bender removed the last gain stage, thus lowering its output volume a bit.

Around late 1975, Colorsound further added to the confusing Tone Bender legacy by renaming the Supa Tone Bender as the Jumbo Tone Bender. The Jumbo was sold through the end of the decade under multiple brands and in a variety of enclosures, including the B&M (Champion) Fuzz, B&M Fuzz Unit, CMI Fuzz Unit, G.B. Fuzz, G.B. Fuzz Unit, or Pro’Traffic Fuzz Unit, or in a smaller enclosure labeled as the Eurotec Black Box Fuzz Module. (The B&M version powered Edwyn Collins’ 1994 hit, “A Girl Like You”—a Bowie-esque, 60’s-style pop gem featuring liberal use of the fuzz’s thuggish buzz.)

No doubt due to the resurgence of fuzz on the Pacific Northwest’s surging grunge and garage-rock scene, Colorsound began releasing Tone Benders (above right) like this 1994 “ram’s head” Big Muff-inspired Jumbo Tone Bender, as well as other iterations, in the mid ’90s. Photo courtesy of Ken Rose/HeroJrMusic.com

The Dark Ages

During the 1980s, fuzz largely fell out of favor among guitarists, so the Tone Bender lay commercially dormant. However, in 1994 Colorsound reissued the 3-transistor, Muff-based Jumbo Tone Bender circuit. The company also unveiled an op-amp-driven Tone Bender bearing no resemblance in tone or circuit to the originals. Closer to a distortion than a fuzz, it is generally regarded as underwhelming at best.

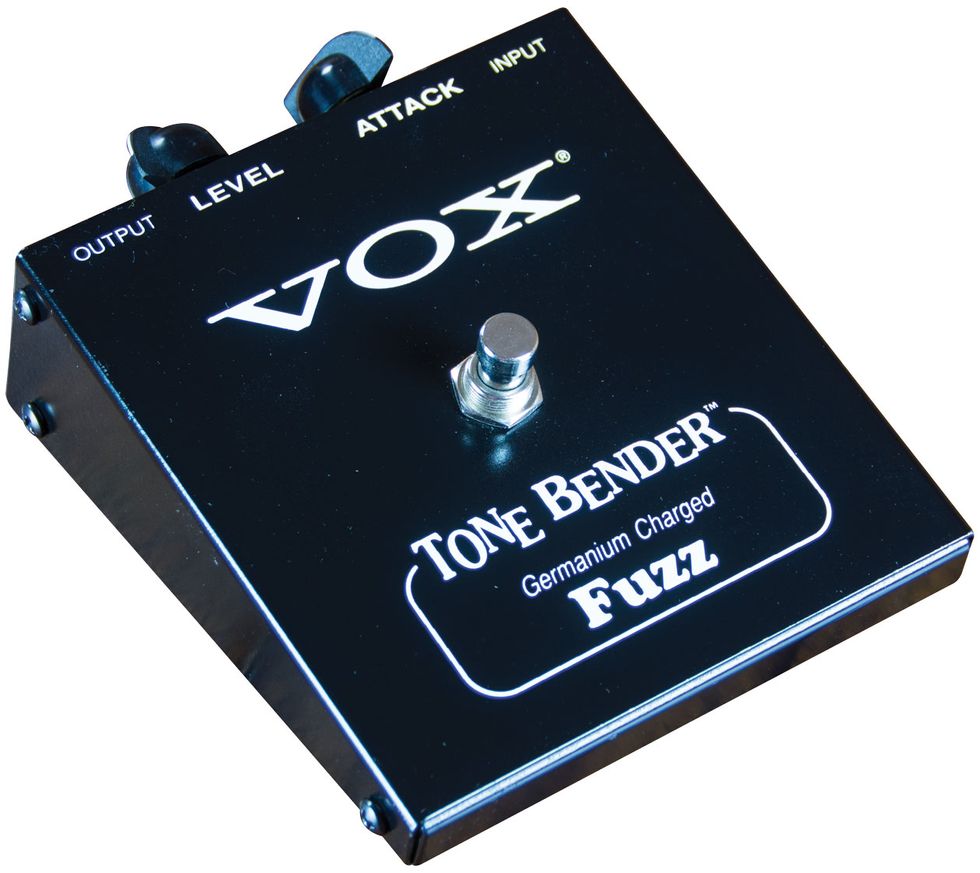

From 1994 to 1997, Vox sold a reissue of its V829 Tone Bender circuit in a smaller housing. Photo courtesy of Guitar Emporium of Louisville

Meanwhile, between 1994 and 1997, Vox issued the V829 Tone Bender, which was based on their late-’60s MkI.5 but housed in a smaller enclosure. Then, in 2004, Gary Hurst released a short run of MkI reissues, which he built himself and issued under his own name—sans any legal connection with Sola Sound, Colorsound, or the Macaris. Perhaps because of this, 2007 saw the “Tone Bender” name trademarked by Macari’s Ltd. in the U.K. and Europe. The legal claiming of the name by the originators paved the way for an official reissue of the Tone Bender.

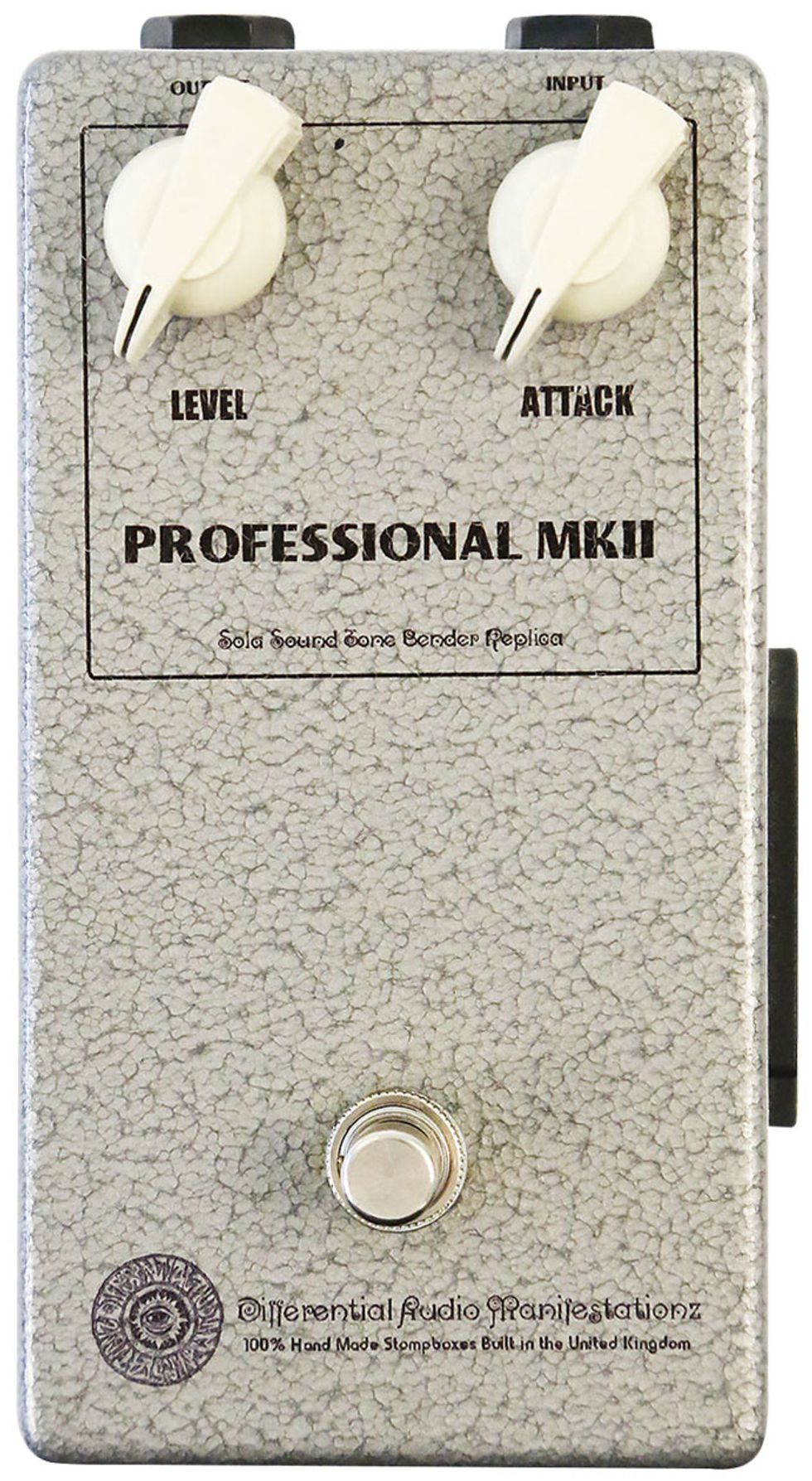

The Now

You don’t have to be any sort of fuzz aficionado whatsoever to see that, today, fuzzes are more popular and abundant than ever. For the last several years, companies, large and small have been reviving circuits of yore and churning out their own takes on the effect. Sola Sound is part of that action, too. After decades being lost in the wilderness, the brand has roared back to life. Since 2009, Sola Sound-branded Tone Bender MkIIs have been available through Macari’s in London (macaris.co.uk). Built by fuzz wizard Dave Main from Differential Audio Manifestationz (D*A*M), these accurate, painstakingly researched recreations are made to exceptional quality and deliver classic Tone Bender tone in spades, allowing the players of today to follow in the hallowed footsteps of those original ’60s guitarists. In fact, after the success of the D*A*M-built MkII reissue, Macari’s also tapped Main and his crew to recreate the MkI.5 and MkIV circuits under the Sola Sound name. In addition to D*A*M, companies such as Pigdog, Castledine, and a host of others now build stunning recreations of the various Tone Benders.

Macari’s of London, owner and originator of the Sola Sound and Colorsound brands, now commissions Dave Main and the team at Differential Audio Manifestationz (D*A*M) to create authentic replicas of vintage Tone Bender circuits, such as this downsized iteration of a MkII. Photo courtesy of Chris Nelson

Tone Bender-style fuzz pedals are perfectly suited to boutique companies due to their ability to devote time to details such as transistor selection and fine-tuning of the circuit bias in each product produced—details that can be difficult to execute for larger outfits that rely on mass production. This is particularly important, as the style of circuit design they use and the temperamental nature of germanium transistors require a level of attention and time expenditure that a machine-made factory line often can’t offer. Thus, the Tone Bender has come full circle. Starting life as a unique wonder built by hand in London, the Tone Bender once again is a handbuilt tone marvel—only now it’s lovingly made at all sorts of shops around the world.

What to Look for in a Tone Bender-Style Fuzz

Present-day guitarists are spoiled for choice when it comes to quality fuzz. And while that is a great situation to find ourselves in, it also means choosing the right fuzz for our needs can be daunting. If you’re looking for a Tone Bender-style stomp but are bewildered by the available choices, here are few tips to help you narrow your search.

Firstly, it’s important to go into this knowing that many Tone Bender clones are built in the spirit and style of the originals—which means many have no DC power option or LED. If these are features you feel you need, be sure to check out whether the clone you are interested in has them. Size is another consideration: Originals were housed in enclosures that are, well, huge by today’s standards. Some clones replicate the larger sizes, while others offer a more compact solution. Check your board and see how much space you can spare before you start your search.

As far as using a Tone Bender goes, the vintage nature of the design means it generally sounds best with your signal going straight from your guitar to the fuzz, before any buffered effects in your signal chain. So be aware that you may need to alter your signal chain to get the sort of iconic tones that have come to be associated with the Tone Bender.

Prior to the MkIII, with its added treble control, Tone Benders came with level and attack controls. It is not unusual to see clones add extra controls. A bias control—which alters the electronic tuning of the transistors—can be useful, as germanium transistors are temperature sensitive. This means the bias—and therefore tone—of the pedal can change, depending on the weather. A bias control, whether an internal trim pot or a standard, top-mounted knob, allows you to compensate for changes in tone due to temperature, as well as shape the overall tone of the pedal.

Price-wise, Tone Benders can be more expensive than other pedals. Due to the scarcity of the original parts, especially germanium transistors, obtaining a Tone Bender clone that is 100-percent true to vintage specs can be quite hard on the wallet. This is because not only are the original transistors hard to obtain, but they are also from an era when components were manufactured with a much wider range of tolerance in the labeled electrical values. (In other words, while a part might be labeled at a certain spec, its actual value when measured with a meter may be off the labeled spec enough to significantly alter how it will sound in a fuzz circuit.) This component inconsistency means discerning builders must spend extra time and effort sifting through and testing the transistors’ actual values. Thus, you are paying for a builder’s ears, skill, and time, as well as the components in the box. For the Tone Bender, transistor selection and biasing is key. Each transistor needs to be individually tested to check for noise levels, and to determine what the gain and leakage of the transistor is. To work with the Tone Bender circuit, gain and leakage of each transistor needs to be within a certain range.

If you cannot find—or afford—a painstaking Tone Bender replica with the extremely rare original OC75 or OC81D transistors, don’t fret. Any quality germanium transistors with the right specs and that have been well selected, tested, and biased can make a fantastic-sounding Tone Bender-style fuzz. Ultimately, selection and biasing of the transistor is much more key than the part number or brand printed on the side of the component.

If you want to go all out and get as close to the originals as possible, I suggest checking out the big guns: D*A*M, Pigdog, and Castledine. All of these brilliant builders are intimately familiar with every aspect of the original pedals and build brilliant recreations with vintage-spec parts. If your budget won’t stretch that far but you still want the best, check out Super Electric Effects. Run by Jimmy Behan, this up-and-coming outfit produces stellar, vintage-spec Tone Bender-style fuzzes at a slightly more affordable price compared to the heavy hitters.