Let’s take a dive into the swirling, shimmering waters of modulation and investigate the evolution of chorus, flanging, and phasing. It’s no exaggeration to suggest that nearly every electric-guitar-based album of the past 40 years—and every hearty pedalboard—features one or more of these classic effects. Their development is integral to the soundtrack of our lives. In charting their history, I’ll cover a mix of classic pedals, vintage studio units, and elusive rarities, giving examples of their use in recorded music.

I’ve had a lifelong fascination with vintage and unusual recording gear and effects, and my company, Soundgas.com, specializes in supplying them. So effects are definitely my bag and I could fill this magazine just writing about vintage phaser pedals. But such passions tend to be personal, so inevitably there will be omissions in this article that, for some readers, are glaring, and for that I apologize.

As a certified delay freak, it’s perhaps odd that my favorite of the three modulation effects, phasing, involves no delay at all. And my favorite chorus pedal happens to be a flanger. And my favorite flanger is the Tape Phase Simulator. Confused? Read on.

Modulation Demystified

What’s modulation? A source signal is modified by another signal, which, in phasing, chorus, and flanging, is a wave created by an oscillator. Chorus and flanging use a modulated delayed signal mixed back in with the source (or dry) signal. The main difference between the two is that chorus requires a longer delay than flanging. Phasing requires no delay: A series of evenly spaced frequency notches are slowly swept across the frequency bandwidth, resulting in phase cancellation. Flanging uses 1 to 5 ms of delay and swept harmonically spaced frequency notches that create deeper phase cancellations. Chorus is very similar to flanging, but uses 5 to 25 ms of delay time to create a thickening or doubling effect, and is often used to shape or widen a stereo image.The Hammond Organ Company was a pioneer in modulation, as they also were in the classic spring reverbs I covered in “Lords of the Springs” in the June 2018 issue. And the first electronic modulation effect was Hammond’s legendary Scanner Vibrato, which debuted in the mid 1930s. This was an electromechanical device that created a rich, distinctive chorus and vibrato effect. In 2015, Analog Outfitters resurrected this device as their Scanner, which was reviewed in PG’s January 2016 issue. That review includes an audio sample where you can hear the Scanner in action, and you can see a demonstration on YouTube, under the search term “Analog Outfitters The Scanner Vibrato & Reverb Effect Demo.”

All You Need Is Flange

If you take two tape machines or turntables and simultaneously play the same recording on each while manually slightly reducing the speed of one of them, you get flanging. Flanging got its name because you achieve this effect by pressing on the rim, or flange, of the tape reel. Or the term was coined by John Lennon—in response to a nonsense explanation of automatic double tracking (ADT) by George Martin. Whichever version you prefer, the technique predates the Beatles by at least a decade, and possibly two. Les Paul used acetate discs as far back as 1945 to achieve the effect, and David S. Gold and Stan Ross, the owners of Hollywood’s famed Gold Star Recording Studio, claim to have released the first commercial recording to feature flanging, “The Big Hurt,” by Toni Fisher, in 1959.Abbey Road engineer Ken Townsend invented ADT in 1966, when John Lennon became tired of recording double-tracked vocals. A second tape machine, previously used as a delay, was varispeeded by an oscillator to mimic the subtle pitch variations of a separate performance. The creative possibilities of this process were not missed by the Fab Four, and Revolver features many examples, although the most famous, Lennon’s vocal on “Tomorrow Never Knows,” is not ADT but an actual doubled recording. The following year, Glyn Johns engineered the Small Faces at Olympic Studios and created one of the most distinctive examples of ’60s flanging: the single “Itchycoo Park.” After that, and, of course, the Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” the studio gloves were off and tape flanging was all over classic ’70s recordings, from David Bowie’s “Station to Station” to Queen’s “Killer Queen” to the Eagles’ “Life in the Fast Lane.”

The Shin-ei Uni-Vibe was a descendent of the company’s Honey Psychedelic Machine and Jax Vibra Chorus—and Soviet propaganda radio transmissions.

Phasers Set to Stun

The first phaser devices came from the Far East, thanks to the propaganda transmissions of Radio Moscow interfering with Japanese medium-wave radio.According to Shin-ei designer Fumio Mieda, the powerful signals bounced off the ionosphere, which varies in height, to create “changes in pitch, phase, and amplitude.” That inspired him to build the circuit that first appeared in the company’s Honey Psychedelic Machine and Jax Vibra Chorus. The latter became better known as the Uni-Vibe. Listen to “Machine Gun” by Jimi Hendrix on the live Band of Gypsys to hear the unmistakable sound of the Uni-Vibe at work.

In 1971, a young Tom Oberheim, the designer of many classic pedals and synthesizers, created the first phaser pedal for Gibson/Maestro: the 3-speed Maestro PS-1 Phase Shifter. The sound of Leslie speaker cabinets intrigued him, and he designed the PS-1 as a more compact option. It went on to sell 60,000 units and became very widely used by guitarists and keyboard players, and heralded the rise of the compact pedal phaser. John Paul Jones used a PS-1 live with Led Zeppelin on “No Quarter,” although the keyboard effect on the original recording was achieved by running the signal through an EMS VCS3 synthesizer. Three years after Oberheim’s PS-1, two of the most influential phaser pedals were introduced: the Electro-Harmonix Small Stone and the MXR Phase 90. Both have had many iterations over the years, and their enduring sonic appeal is a testament to their superb design.

The many flavors of Small Stone include the originals by Electro-Harmonix, with the rare treadle model (upper left) and their more contemporary counterparts, as well as versions made under license by Russia’s Sovtek.

Totally Stoned

I’ve owned a great many incarnations of the David Cockerell-designed Small Stone and still have several early examples from which I would not be parted. They just have that sound. Cockerell was also the designer of the famed EMS Synthi Hi-Fli, which I wrote about in PG’s July 2018 issue in “Monster Mutilators: Vintage Guitar Synth Pedals.” That cumbersome device was a key part of David Gilmour’s mid-’70s recordings with Pink Floyd.When you want the sound of a Small Stone, nothing else comes close, save for the clones several modern boutique pedal makers have been inspired to build. I could write a whole article on the Small Stone alone: from its gestation amongst the circuitry of the EMS Synthi Hi-Fli to the very early Electro-Harmonix versions, through the Sovtek years to today’s Nano.

There can be drawbacks with vintage Stones, from volume drops to noise, and there’s always the potential that used ones have been messed with, but it’s rarely something beyond the wit of a competent tech. I believe a good Small Stone is an essential ingredient in any serious audio arsenal, whether it’s for the studio or on a pedalboard.

While I’ve been less impressed with some later vintage versions of the Bad Stone variant, I have a very early example that is quite stunning, as is the rare treadle version. You can hear the Small Stone everywhere, from Jean Michel Jarre’s Oxygène to Radiohead’s OK Computer.

In addition to the ubiquitous Phase 90—used by David Gilmour, Jimmy Page, Eddie Van Halen, and many others—MXR also created the Phase 45 and Phase 100, which have more subtle sonic profiles.

Orange Juice

The MXR Phase 90 is a sonic giant in a minuscule enclosure. It was introduced in 1974 and quickly found favor with the era’s biggest guitarists, including David Gilmour, Jimmy Page, and Eddie Van Halen. Gilmour adopted his after employing the Uni-Vibe for the Wish You Were Here sessions. Page used a Phase 90 live with Led Zeppelin. And Eddie? “Eruption.”The early script-logo Phase 90s are more sought by collectors, and the very earliest, housed in ultra-lightweight aluminum “Bud Box” enclosures, are the ultimate in desirability. I’ve had many Phase 90s over the years, and there is little difference between script and block logo pedals of similar vintage, aside from the paintwork. But once I found a “Bud Box” version, my search ended. It sounds simply stunning. MXR also produced the Phase 45 and Phase 100, and both are excellent.

The Gerd Schulte Audio Elektronik Compact Phasing ‘A’ is known as the “krautrock phaser,” but guitarists can find a more relatable use of the device in “Catch the Rainbow” on the 1975 debut album by Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow.

The Krautrock Phaser

Remember when I mentioned that my favorite chorus pedal was actually a flanger? Well, my most coveted phaser is … actually a phaser. (Had you for a moment, didn’t I?) It’s the snappily named Gerd Schulte Audio Elektronik Compact Phasing ‘A’ Number 1. This Germany-made optical phase shifter was used so extensively by many of the most influential German bands of the ’70s that it became known as the “krautrock phaser.” If you’ve heard the whooshing sound of Tangerine Dream’s Mellotron on “Phaedra” or the thick sweep of Kraftwerk’s synthesizers on “Autobahn,” you’ve heard a Schulte. It can be counterintuitive to use, but it sounds like no other phaser and has a wide palette of effects—especially when partnered with a custom control pedal, which unleashes several otherwise hidden settings. Ritchie Blackmore and Jon Lord of Deep Purple also used the device, so its credentials are as much “rock” as “kraut.”

The chorus circuit of the famed Roland JC-120 amp gave birth to the company’s first Boss pedal, the CE-1 Chorus Ensemble, which has been used on tracks by the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Rush, the Smiths, and Cyndi Lauper.

Join the Choruses

Roland’s Jazz Chorus amplifiers have proven hugely popular since their launch in 1975, finding favor with such bands as the Police, the Cure, and Steely Dan. Based on a bucket-brigade device (BBD)—an analog chip developed in 1969 by two engineers at Phillips Research Labs—the amp’s distinctive onboard chorus circuit was a hit, so when Roland launched Boss, their fledgling effects arm, it was with the pedal version of the JC’s chorus, known as the Chorus Ensemble or CE-1. As the 1970s gave way to the ’80s, the sound of chorus was everywhere. Red Hot Chili Peppers’ John Frusciante used a CE-1 on many of the band’s recordings, perhaps most notably, “Under the Bridge.”Peter Hook of Joy Division and New Order created his signature bass sound using the original Electro-Harmonix Clone Theory, and Kurt Cobain was another EHX chorus fan, owning both a Polychorus and a Small Clone. The latter contributed greatly to his guitar sound on Nevermind. I’ve never had a vintage Small Clone, but for over a decade my pedalboard chorus has been the Analog Man Bi-Chorus, which is based on the Small Clone.

While more recent examples of the EHX Electric Mistress Flanger/Filer Matrix are 9V, the original versions were 18V and had a distinctive tonal quality that inspired some of David Gilmour’s epic tones on Animals, The Wall, and his first solo album.

When a Chorus Is Not a Chorus

So, I mentioned earlier—twice, actually—that my favorite chorus isn’t really a chorus. It happens to be a flanger designed by David Cockerell for Electro-Harmonix. The original 18V Electric Mistress is the stuff of legend. Nothing that came thereafter bearing the name could touch the first version (of which there were several iterations). David Gilmour and Andy Summers both favored this flanger over then-contemporary chorus pedals. If you get a good one, you’ll be unlikely to ever let go of it, but do beware if you’re buying untried, for not all 18V Mistresses were created equal. In addition, the effects of age, misuse, and possible tampering by the uninitiated make these an especially tricky vintage item to purchase successfully online. Gilmour adopted his after the recording of Animals with Pink Floyd was completed. He used it for much of that tour and it was featured prominently on his first solo album. While the Electric Mistress was only used sparingly while recording The Wall, Gilmour had two boards built by Pete Cornish for The Wall Tour, with an 18V Mistress on each. Andy Summers used his on many Police recordings.

Original Mu-Tron boxes are legendary and have inspired many pedal builders and players with their three-dimensional tones. Their Phasor series of pedals, like the Phasor II (left), were compact and stage-ready, but the Bi-Phase (right) really found its home in the studio, becoming an essential element of dub recordings as well as rock albums, including Smashing Pumpkins’ Siamese Dream.

Phased In

Let’s get back to phasers. As I said, I could fill this magazine with ripping yarns about this device. I especially enjoy Mu-Tron Phasors, from their first Phasor though the Phasor II, and on to the big daddy that stretched the definition of a pedal: the Mu-Tron Bi-Phase. All are excellent effects, but it’s the Bi-Phase that I have to touch on here. It remains a studio essential much loved by dub producers from Lee “Scratch” Perry onwards, and was the effect at the heart of the Smashing Pumpkins’ Siamese Dream. The album’s producer, Butch Vig, has described the Bi-Phase as “One of the secrets to our secret sound—we run everything through it. Everything. It’s fabulous.” And producer Daniel Boyle reunited 82-year-old Lee “Scratch” Perry with a Bi-Phase for their 2016 album, Back on the Controls, highlighting the monstrously proportioned blue phaser’s impeccable dub credentials once more.

Producer Tony Visconti was an early adopter of Eventide’s Instant Flanger, which appears on David Bowie’s 1980 Scary Monsters album. It also played a key role in the soundtrack for the 1984 movie of Frank Herbert’s sci-fi novel Dune.

Another remarkable phasing device is the Eventide Clock Works Instant Phaser PS 101. Even though tape flanging was faster for John Lennon than doubling his vocal performances, it was a time-consuming process. Because studio time is expensive, pro audio manufacturers were keen to find a more convenient solution. Enter the PS101 in 1971. This rack unit was the result of Eventide’s attempts to create an electronic flanger. It delivered thick, lush phasing and mono-to-stereo effects. The PS 101 became a hit and was used on many classic recordings. Jimmy Page employed it while producing Physical Graffiti, both for his guitar and for John Bonham’s kit. Listen to “In My Time of Dying” and “Kashmir” for epic examples. Page also used an MXR Phase 90 live.

Roland’s Rack Series—including the SDD-320 Dimension D chorus, the SPH-323 Phase Shifter, and the SBF-325 Stereo Flanger—quickly became studio favorites, employed by a range of producers, engineers, and guitarists.

The next big step in electronic flanging followed in 1976, with the arrival of the Eventide Instant Flanger, which was used by Tony Visconti for the distinctive piano sound on David Bowie’s “Ashes to Ashes,” and the famous blue face MXR Flanger/Doubler, which was also loved by dub producers. Roland’s Rack Series brought the excellent SDD-320 Dimension D chorus, the SPH-323 Phase Shifter, and the SBF-325 Stereo Flanger, which all remain widely used and sought-after. Stevie Ray Vaughan fell in love with the sound of the Dimension D when he worked with Nile Rogers and David Bowie on Let’s Dance, and it became one of his secret studio weapons, used in the mixing stage to subtly widen his guitar on solos.

More Modulators

The aviary of chorus, phasing, and flanging has even more rare birds. Here’s a smattering of additional species you might find interesting:

These are three iterations of the EMS Synthi Hi-Fli, which was responsible for many of the glorious modulation guitar effects on Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon.

EMS Synthi Hi-Fli. It may seem strange to consider using one of the most complex and expensive guitar effects on the planet as a simple phaser, but David Cockerell’s masterpiece is quite superb and flexible when put to the task. If you don’t have a Hi-Fli on hand, console yourself with an early Small Stone—an aural close relative.

It’s double the fun with the AMS DM 2-20 Tape Phase Simulator, which uses two delay lines to achieve the through-zero effect, allowing for more dramatic phasing and flanging sounds.

AMS DM 2-20 Tape Phase Simulator. My favorite flanger is, indeed, this phaser. The AMS DM 2-20 is without equal, and one of the only vintage units to really perfectly nail the through-zero effect by using two delay lines rather than one.

Now, it’s worth taking one more digression to explain the through-zero effect. In flanging, one signal is played back at a fixed rate while the other is alternately slowed down and speeded up, and it either lags behind or moves in front of the original signal. When the modulated signal momentarily aligns in time with the original, total phase cancellation briefly occurs. That’s called the “zero point.” In the AMS Tape Phase Simulator, this effect is far more pronounced and dramatic than with most traditional flangers and requires complex and clever circuitry. Achieving the through-zero effect also requires two delay lines, as both the original and the modulated signal have to be capable of moving in time.

Marshall Time Modulator 5002 A System. Legend has it that Stephen St. Croix’s incredible device was designed in 1975 to win a bet and was promptly exhibited at the AES convention a few days later. Finally released in 1979, the MTM is capable of a mind-bending array of effects, including positive (or additive) flanging, negative (or subtractive) flanging, automatic double and triple tracking, resonant flanging, and Leslie sounds. Stevie Wonder used one on Songs in the Key of Life. Soundgas’ studio MTM came from Musicland Studios in Munich and was used on Queen’s “Another One Bites the Dust.” That song’s reversed piano sound displays all the hallmarks of an MTM. The later 5402 A System is even rarer and features extended delay times for even wilder effects.

AMS DMX-1580S Digital Delay and DMX-K Chorus Controller. The AMS stereo digital delay, fitted with a controller board and paired with the ultra-rare Chorus Controller, is your ticket to an ultimate classic ’80s stereo pitch-shifting chorus and vibrato that ranges from subtle sweetening to full-blown craziness.

Roland PH-830 Stereo Rack Phaser. The ultimate Roland monster rack phaser features two channels for true stereo operation. It’s very rare and simply superb.

Foxrox Paradox TZF. I’ve not heard later versions, but the original blue TZF was the first pedal I found that completely blew me away with its classic through-zero flanging effect. I still have it and use it almost daily.

Publison DHM 89 B2 Stereo Digital Audio Computer. This is a super-rare early digital pitch shifter/delay that’s capable of classic chorus sounds. Listen to the guitars on Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time” for an example. But beware when buying: Publison scratched off all chip IDs and schematics are non-existent outside of France. Repairs can be expensive, but these are stunning units and worth the trouble.

Pefftronics Super Rand-O-Matic SB-101. Dating from the end of the last millennium, but sounding unlike anything that had gone before or has come since, this unassuming little box of joy does chorus, flanging, and phasing, and a whole lot more. Check out this rare stomp if you can.

Lovetone The Flange With No Name. This is the rarest Lovetone pedal of all, and I’ve yet to corral one. If it’s half as good as the Doppelganger (their gorgeous twin phaser), then I’m not going to stop searching until I finally find mine.

Another futuristic-looking member of the Mu-Tron clan, the Flanger has parameters that are manipulated—after their initial settings—by a treadle.

Mu-Tron Flanger. The monster Mu-Tron treadle-controlled Flanger is by no means the wildest of the Mu-Tron family of devices, but, in keeping with its phase-shifting brethren, it’s a sonic delight. As with many Mu-Tron stomps, you might need a bigger pedalboard to accommodate it.

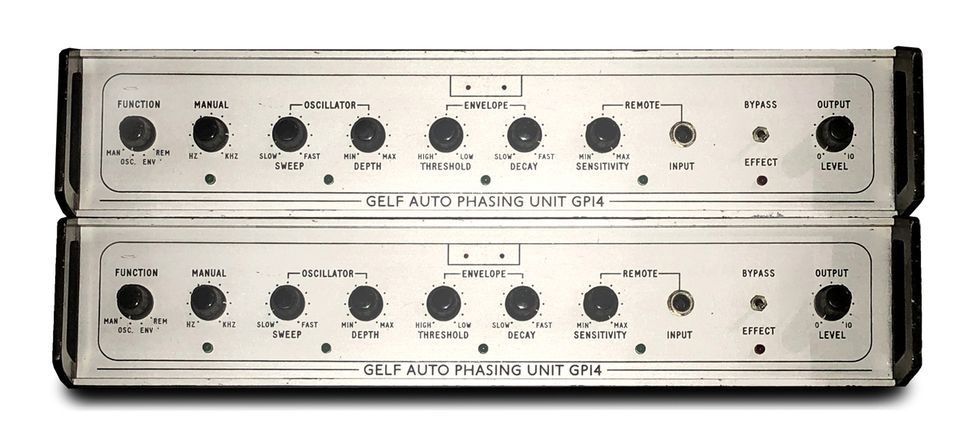

This pair of Gelf Auto Phasing Units reside in the author’s studio, but were originally in Pink Floyd’s legendary room, Britannia Row. Their dials are basic but allow for precise control of phasing effects.

Gelf Auto Phasing Unit. These are insanely rare and very little is known about their development and manufacture, but their sound is legendary. We have a pair in the Soundgas studio that came from Pink Floyd’s Britannia Row Studios.

Dytronics CS-5 Tri-Stereo Chorus. Session royalty, including Michael Landau, Steve Lukather, and Dann Huff, used this huge-sounding rack chorus to achieve thickly layered ’80s guitar tones.

A/DA Final Phase and A/DA Flanger. Both of these pedals are worth investigating—whether vintage originals or ’90s and more recent reissues. The flanger, in particularly, is a serious contender for the sonically astute, and especially if you love getting wilder results.

If you’re looking for classic phaser “swoosh,” a Roland Jet Phaser is the charm—great for adding sonic magic to both guitar and bass.

Roland Jet Phaser. It wasn’t what Ernie Isley used on “That Lady”—he actually plugged into a Big Muff and a Maestro PS-1—but it gets you very close in a single pedal. And it’s part of the core sonic strategy of bass great Larry Graham.

Apologies for any omissions, but please feel free to chip in with comments and suggestions at the end of this article on premierguitar.com.

Classic recordings have a wealth of timeless examples of phasing, flanging, and chorus.

First up:

Jimi Hendrix’s “Machine Gun”This distinctive guitar tone is practically part of the genetic code of the rock guitar canon. And, of course, it’s live, unadulterated Hendrix at his improvising best, displaying the virtues of the Uni-Vibe phaser—set on stun.

David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance”

It’s Bowie’s song, but the scene-stealing solo is by Stevie Ray Vaughan, aided by the Roland Rack Series SDD-320 Dimension D chorus. After producer Nile Rodgers turned Vaughan on to the device, it became his secret studio weapon.

David Gilmour’s “Mihalis”

Listen to one of the most hallowed flanger pedals, the Electro-Harmonix Electric Mistress, and go deep and wide under the control of David Gilmour on “Mihalis,” the opening track from his debut solo album, simply titled David Gilmour.