Gibson's history is rich with acoustic instruments built to be accessibly priced. The company's beloved and underrated B series guitars from the '60s, for instance, used laminate mahogany sides to make them more attainable. Even the legendary J-45 began as a relatively affordable model—cleverly using that beautiful sunburst finish to conceal less-than-perfect spruce pieces that were in short supply around World War II.

For most of recent history, Gibson's acoustics occupied more rarified upmarket territory—largely leaving the mid-price business to their Asia-built Epiphone Masterbilt instruments, Taylor and Martin's Mexico-built entry-level flattops, and a revolving cast of overseas manufacturers.

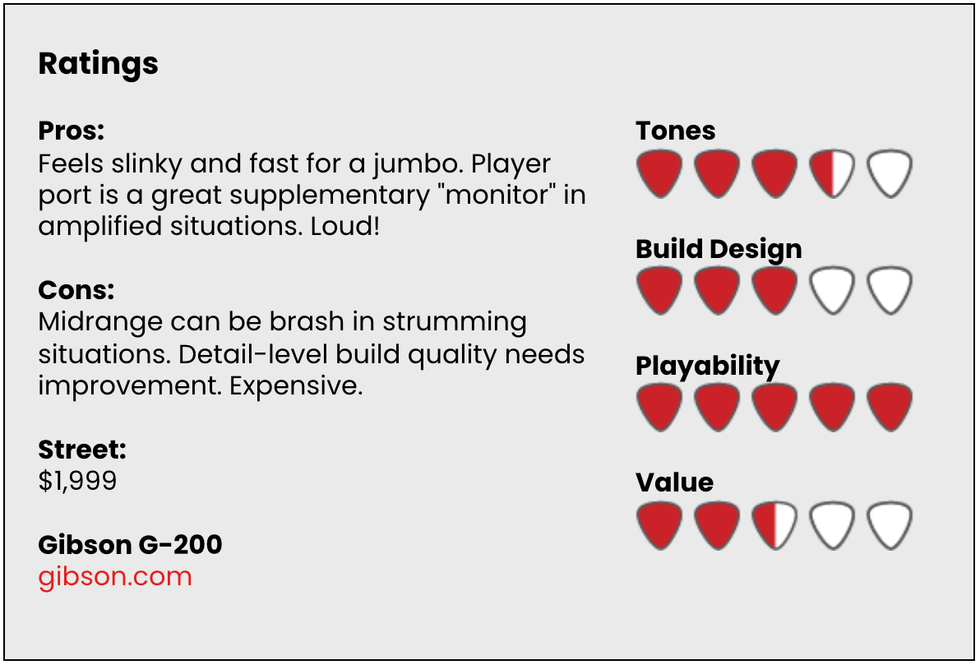

It's easy to understand Gibson's reticence to enter the mid-price acoustic game with a Gibson-branded guitar. It's a brutally competitive market: Asia-built instruments leverage lower manufacturing overhead to ape more expensive American inspirations, while legacy American brands offer less luxuriously ornamented guitars built with alternative and laminate woods—often in facilities in Mexico. With the Generation Collection of acoustics, Gibson chose a middle path to the mid-price market. Rather than move production to Mexico or overseas, or use laminates or wood composite materials, the Generation guitars are built with solid woods in the same Bozeman, Montana, facility that makes the company's top-shelf flattops. That means the guitars are pretty austere and more expensive than a lot of the mid-price competition. In fact, you could argue that the highest-priced members of the Generation series, the $1,599 G-Writer and $1,999 G-200, are not mid-priced at all. Yet the G-00 and G-200 offer a compelling playing experience, and each model is built with a side port (which Gibson calls the Player Port) that enables a subtly more intimate means of relating to each guitar's dynamic potential. For this review we looked at the two models that bookend the Generation Collection: the G-00 and G-200.

G-00: A Baby with Big Personality

Gibson G-00

For many players, this author included, the Gibson L-00 is a magical little instrument. Not only does it conjure images of Bob Dylan shattering folk convention circa '65 with his very similar Nick Lucas model, but it's one of those flattops that, when built right, occupies a sweet spot between power and sensitivity. They are fantastic fingerstyle instruments, and the Generation Collection incarnation of the L-00, the G-00, is particularly well suited for that task.

At $999, the G-00 is the least expensive of the Generation Collection, and it might be the instrument that wears the series' no-frills dressing most gracefully. The slim, compact lines are flattered by the lack of binding, giving the guitar an earthy, elemental essence that suits its folky associations. The solid walnut back and sides are beautiful pieces of lumber with abundant swirl and figuring that lend the otherwise plain-Jane styling a lot of personality. The solid spruce top, meanwhile, is straight-grained, high-quality wood. The neck is carved from a single piece of mahogany-like utile, and the headstock (which is fashioned from two additional "wing" sections of utile) is capped with walnut. The striped ebony, with its orange-red streak that runs from the soundhole to the 5th fret, lends a subtle sense of flash to the guitar's otherwise spartan visage, and the fretwork is largely flawless.

Though the G-00 has a lovely natural glow, the nitrocellulose satin finish seems exceedingly thin. That's no bad thing if you like your tone as wooden and unadulterated as possible, but if you're the kind of fastidious player that likes to keep your instrument in perfect shape you may long for a more robust finish. The G-00 also shows some signs of economizing on the guitar's interior, which is more visible for the presence of the player port. A sizable errant glue smear was plain to see just inside the player port and several sections of bracing could have benefitted from another pass with sandpaper. These aren't imperfections that affect sound or playability in any way. But they are details you'd like to see looked after more carefully when you're shelling out a grand for an instrument.

"The G-00 sounds especially lovely in detuned settings, exhibiting bass richness that's rare in a guitar this size."

Wrapped Up in It

One of the really lovely things about playing a guitar with the compact dimensions of the G-00 is the way it feels like an extension of yourself. Big guitars can sound beastly, but the G-00 lends a natural, effortless feel to the playing experience. The neck, which feels like a cross between a D and C profile, walks the line between slim and substantial gracefully. I might have preferred a touch more girth, but there's no arguing with the ease of playability.

The sense of being at one with the guitar is enhanced slightly by the player port. This design feature was, according to Gibson, a primary impetus behind building this line (the company uncovered blueprints from 1964 proposing a J-45 with a relocated sound port). Sound ports have been features on boutique instruments for decades. Just as on many of those guitars, the effect of the sound port is subtle on the G-00. But if you tune the guitar to an open chord and play the guitar while covering and uncovering the port, you'll hear a real difference—primarily in the way the low end blooms and the treble tones ring. And by the way, the G-00 sounds especially lovely in detuned settings, exhibiting bass richness that's uncommon in a guitar this size in this price range.

The G-00 does not come with a pickup, but as we found when testing the pickup-equipped G-200, the port works effectively as a supplementary monitoring solution in quiet performance situations. How it fits into the aesthetic whole is subjective. And how it affects performance will vary from player to player, but, at least in my experience, it lent an extra sense of detail in fingerpicking situations.

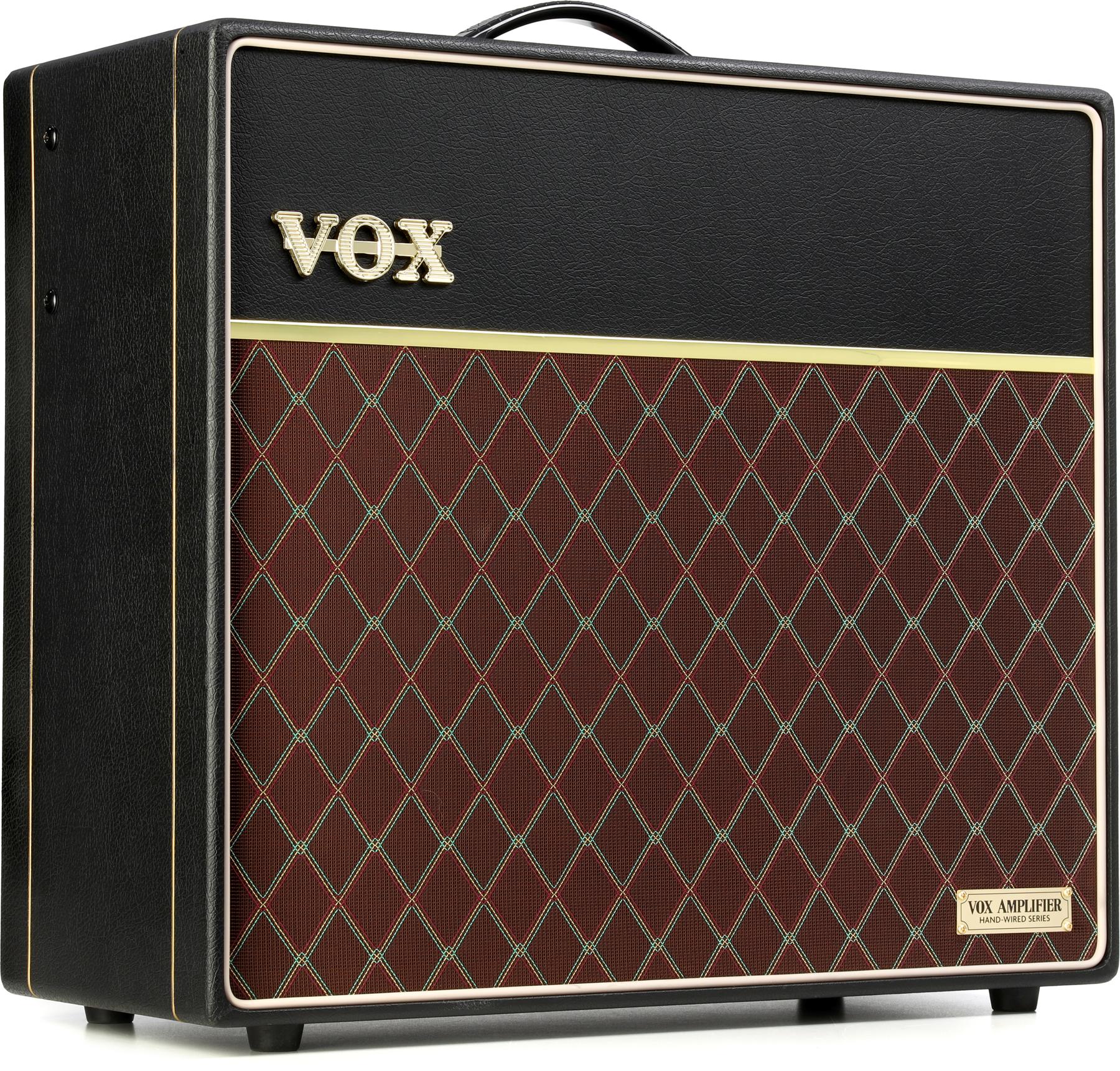

G-200: Mama Bear Makes a Racket

Gibson G-200

Gibson's list of iconic designs is lengthy to say the least. But while it may not be as famous as some of its other acoustic and electric kin, the J-200 is one of the most beautiful and impressive Gibsons of all. The Generation Collection version, the G-200, does many things that a good jumbo should. It compels a player to dig deep into chugging, choogling rhythm moves and it's loud. Man, is it ever loud. In the case of the G-200, though, that loud can sound just a touch one-dimensional at times. How you relate to strong midrange may determine how much you love or just like the G-200 in a strumming context. But it can sometimes read as brash—particularly when you use the heavy rhythm approach that makes a J-200 the acoustic of choice for power strummers like Pete Townshend.

The bass tones are quite pleasing—a quality revealed, again, by the presence of the player port. And if you use a lighter, more dynamic flatpicking approach, you can coax a much more even tone profile that lets the resonant low end and ringing highs shine. Jangly Johnny Marr and Peter Buck arpeggios sound lovely for this reason—especially when you use a capo. In fingerstyle situations, the guitar feels a little less dynamic and balanced, largely because coaxing an even response from a body this big takes a fair bit of muscle. But when you do get a feel for how to make the G-200 sing with a lighter touch, the walnut and spruce tonewood recipe dishes some very pretty tones, indeed.

Gibson G-200 Review by premierguitar

Stream Gibson G-200 Review by premierguitar on desktop and mobile. Play over 265 million tracks for free on SoundCloud.Like the G-00, the G-200 is an absolutely lovely player. While the action feels slinky and low-ish, there isn't a buzzing string to be found anywhere—and that's a beautiful thing given how much the guitar begs to be played hard and that the cutaway makes lead runs all the way up to the 20th fret a workable proposition.

But while the playability is hard to top—and reflects a great deal of care for how this guitar was built and set up—there is still evidence of some economizing to keep the price in that high-mid category. As on the G-00, there are clearly rough cuts on the bracing that could have been remedied with a light pass with the sanding block. And while none of that undoes the satisfaction of playing a guitar that feels this smooth, it does potentially undo some of the enthusiasm you might feel after parting with nearly $2K for the instrument. What's more, the soundhole revealed a less than flattering view of the wire connecting the otherwise excellent L.R. Baggs Element Bronze preamp to the soundhole-mounted volume control. You don't want to use hardware to affix a length of wire to bracing or the top that are so critical to tone, but there must be some way to fix a wire so you don't see it flopping through the player port.

"The guitar begs to be played hard and the cutaway makes lead runs all the way up to the 20th fret a workable proposition."

The Verdict

Gibson is taking a noble shot at threading a needle with the Generation Collection. The company's commitment to building a more affordable flattop in the U.S. is a welcome development—not to mention a good way to help guarantee a little more resale value on the back end for players that see a lot of churn in their collections.

There is a lot that is special about the G-00. In tone terms, it compares favorably with more expensive Bozeman-built flattops in the high-mid-price grand concert category. The playability is superb, and the player port adds a subtle but unmistakable extra dose of detail in fingerstyle situations. The G-200 is less flattered by the Generation Collection recipe—at least in its new-from-the-factory state. The midrange could use some of the mellowing that often comes with the passing of a few seasons and sessions. And it's hard to avoid longing for a little more responsiveness to a light touch. That said, it sounds—and feels—massive in detuned situations and its copious capacity for volume makes the possibilities of the G-200 as a rhythm guitar super tantalizing. Whether or not you'll ultimately want to spend a few hundred more for a Gibson with more upscale appointments (a solid rosewood-backed J-45 Studio, for instance, costs just $250 more) will be down to how you bond with the guitar in person. But both guitars exhibit tons of potential for the right player.