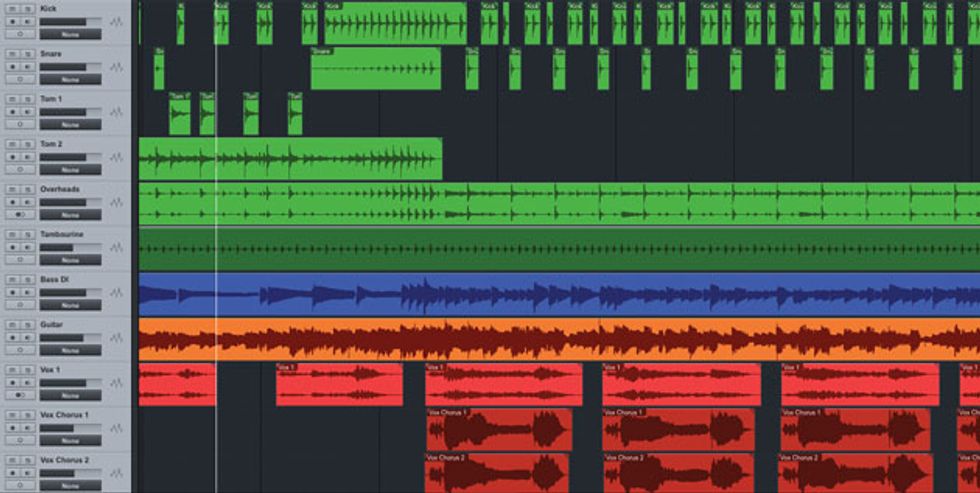

This session has been thoroughly cleaned. The kick, snare, and tom tracks are edited. The overheads need no cleaning—they’re supposed to contain all instruments. The tambourine was overdubbed, so no cleaning required. The bass was recorded direct—no cleaning required. There was only one section where the electric guitar didn’t play (not shown), where it was cleaned. The lead vocal, recorded in a large hall with stereo mics to capture reverb, was only gently cleaned. Chorus vocals have been cleaned, but not too stringently in order to maintain their live sound.

In last moth’s column [“Cleaning a Mix,” January 2014] we began cleaning our tracks in anticipation of actual mixing. We started by cutting the “bleed” among the various drum set mics to clarify the sound and reduce potential phase cancellation. But drums aren’t the only candidates for cleaning—anything recorded via microphone while another instrument or voice was sounding could have bleed issues.

Let’s go down the list of instruments.

Electric bass: Often recorded direct, in which case bleed isn’t a problem, though it may be if the bass amp is miked. Listen carefully: If the microphone is close to the speaker and the amp is turned up, the amp signal will be so much louder than the bleed that it probably won’t matter. Just cut out any larger sections of the track where the bass isn’t playing and bleed is audible.

Electric guitar: In most cases an electric guitar amp recorded in an ensemble situation will be close- miked. This means the bleed will be insignificant in comparison to the guitar’s signal. You’ll probably only need to cut sections where the guitar isn’t playing and bleed is audible.

Synthesizers and electronic/electric keyboards: These are almost always recorded direct without using microphones, so bleed will not be an issue other than possible hiss or hum from the instrument itself. One exception: Recording anything through a real Leslie rotating speaker cabinet requires as many as three microphones (two on the top rotor for stereo, and one on the bass rotor). Those mics are often pulled back a foot or two or three to smooth out response and reduce wind noise from the rotors. This opens them up for potential bleed issues if the organ is recorded at the same time as drums or other instruments without isolation.

Vocals: There may be bleed if the vocalist is singing in the same room as the band or is playing an instrument while singing. Hopefully the vocal mic was at least somewhat isolated. If not, hopefully the vocalist was singing loudly enough that bleed isn’t a problem, and you can just cut out the sections where the singer isn’t singing. Be careful about cleaning vocal tracks, especially lead vocals, too zealously. If you cut out the vocalist’s breaths and even some of the odd mouth pops and clicks, the performance can start to sound sterile and unnatural. However, throat clearing, bumps from hitting the mic stand, obnoxious mouth noise, whistling breaths, and so on, are all candidates for excision.

Acoustic guitar or bass: While these instruments are often amplified onstage using piezo pickup systems, in the studio they’re usually miked. If they’re played in the same space as drums or electric guitar, bleed can be a real problem. Acoustic stringed instruments just don’t create enough volume to overcome significant mic bleed. The best solution is to isolate such instruments or simply overdub later. Otherwise, careful cleaning may help bring the bleed under control.

Acoustic piano: As with acoustic guitar and acoustic bass, acoustic piano can be susceptible to bleed. A lot depends on where the microphones are placed, whether the piano’s lid is open, where the piano is placed in relation to the other instruments, and so on. I’ve worked on a number of live multitrack recordings by jazz ensembles, both big bands and small combos. Bleed into the piano mics is always a major issue. But with a combination of filtering (as described in last month’s column) and track surgery, piano tracks can be cleaned up, at least somewhat.

Pianos are often captured using two mics: one on the high strings and one on the low ones. This means you can sometimes process those mics differently—different filter points for the high and low mics, for example. You could even experiment with automating the filter frequencies to follow what each microphone captures throughout a song, though this could be a tedious process. Often though, the piano plays notes that get into the bass range, making it hard to scrub bass and bass drum bleed, as well as the mid and treble ranges, making it hard to clean guitar, snare drum, and cymbal bleed.

Heavy bleed into piano mics leads me to the final point for this month: You can only do so much. If you go beyond realistic cleaning, it will become audible to listeners and the music will lose its life and energy. There is definitely a point of diminishing returns when it comes to track cleaning. My advice is to get the “big stuff”—the most audible bleed problems. The rest you simply have to live with, or figure out a way to use the bleed as ambience in the track. Remember, some of the best recordings in history were made with the band all in one space—bleed be damned! Bleed can add a certain “live” quality and energy to band tracks. Don’t lose that by getting carried away with your DAW tools.