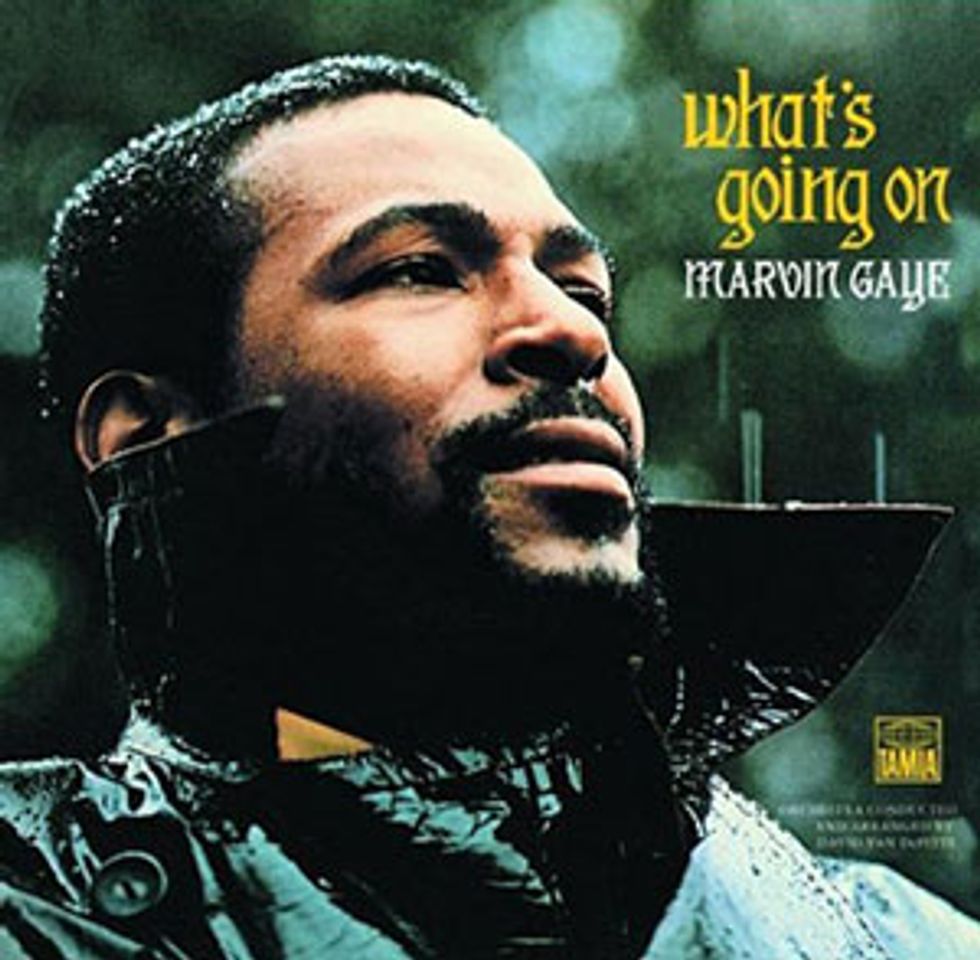

To hear an example of how to play for the song, listen to “What’s Going On” by Marvin Gaye and marvel in the beauty of James Jamerson’s simple low-end groove.

A short time ago, I was at a bar with some of my touring friends just enjoying some late-night shuffleboard action and stories of time on the road. Sadly, the jukebox wasn’t offering much in the way of entertainment by belting out mind-numbing dancehall and the latest dubstep from the self-appointed DJ of the hour. The music was just glorified ambient noise on this chill evening—insipid and uninspiring.

But the forces of good soon took over when an anonymous bar patron loaded the jukebox with some musical sensibility. The back room speakers started vibrating with the opening strain of “What’s Going On” by Marvin Gaye, and suddenly, moods started to change and heads started to bob. It was as if the wet blanket was pulled off the night. My drummer turned to me at that moment while air playing Jamerson’s bass part and said, “Man, listen to that—so simple, so perfect. Why isn’t it like this anymore?”

Ah, the good ol’ days. We seemed to live more simply then. The days were all about just playing music—simple, sweet music. We didn’t concern ourselves with licks and flash, or effects and solos. We played for one reason: To woo women! But then drugs eased into our culture and so did effects pedals. Labels were directing traffic from behind the dark curtains, and many hundreds of amazing musicians were being screwed out of pay, credit, and residuals. Good ol’ days, indeed.

These “easier” days (or much more difficult if you ask someone who recorded 50+ years ago) were not better or worse. We simply didn’t know better. When recording was in its infancy, bassists were rarely heard, and the flash and glory went to the melodic instruments: Django had his guitar, Satchmo his trumpet, and Woody his clarinet. The amazing bassists backing these legends were playing perfect, simple (and probably scripted) parts for the arrangement. The solos came and went, and we just did our jobs holding it together. We hadn’t moved into busy bass-lick-land … yet.

As the electric-bass parts on records moved from quarter-notes on 1 and 3 to dotted eighths to blazing-fast Jaco licks, bassists started feeling the freedom of expression. Thankfully, producers and more level-headed bassists kept it pretty much in check during the recording process, but live playing took on a whole new approach. It seemed that playing more notes—or that dreaded fill after every eight bars—became the norm rather than the exception. As the urge to be busier crept in, bassists that were usually easy to deal with were getting fired from gigs.

Here in Nashville, I learned a hard lesson very early on. I was right-off-the-bus new to town and was hired to play a showcase for an aspiring singer who happened to be a friend. The rest of the band was made up of hired A-list players from Nashville, but instead of using a trusted gun on bass, I was brought in. After the first rehearsal, no one from the band spoke to me, but the manager of the artist took me aside. “Man, it was good,” he said. “But can you kinda not play so much? Like, be cool with it, you know? Let the guy soloing solo.”

After that amazingly humbling experience, it still took several years before those words actually sunk in. As bassists, our role as the foundation can get skewed, especially after we hear John Entwistle or Cliff Burton playing so many notes. We can get excited in a hurry, and if we don’t show restraint, the groove or the song we’re tracking can lose focus just as quickly.

There is an expression I’ve heard around Music City that rings true throughout the world: Play for the song. This means it’s your job to capture the essence of what the producer or songwriter has envisioned when coming up with the formula to make the song come to life. Let’s set aside your style, reputation, and resume for one minute, and figure out how it all fits in.

For example, you’ve been hired to play on a rock track—just straight-ahead, eighth-note, pounding rock. It’s a hard-edged song but you decide to throw good sense out the window and play a 32nd-note slap groove in the verses. This is not playing to the song. Just because you can play a slap line doesn’t mean you should play it. You can, however, take this moment to maybe put one big pop in the bridge to add something different, which endears you to the producer. It’s a delicate combination of taste, talent, and ultimately, execution.

The real crime usually happens in a live situation. First of all, it’s a bit looser than a recording session and generally without others looking over your shoulder at what you’re playing. Beer is flowing and people are rocking, so you decide to play whatever you want. But are you really making the songs better by flashing all your chops every time there is musical daylight? Leave the hole filling to the drummer. Your job is to anchor the whole thing and shine when it’s your time, which is actually all the time if you anchor it well.

But why do the Entwistle and Burton types get all the fun? Well, because they are in a band and maybe their bass riffs are the song, which guarantees they won’t go away. The rest of us mortals have to rely on our broad musical knowledge and taste to play just the right notes and grooves for the songs we’re working on.

Playing for the song doesn’t mean there’s no artistic feeling involved or that your style can’t be incorporated. Those early recordings sound so good because the bassists aren’t stepping all over the other players. And quite frankly, they wanted to keep working. Being the tasteful bassist goes further than being the flashy one, and it’ll help you keep working, too.

Steve Cook has been fighting his rock-star frontman

urges for decades, holding down the low

end for such artists as Steve Cropper, Sister

Hazel, and Phil Vassar. Join in his “touring

therapy” on Twitter @shinybass.

Steve Cook has been fighting his rock-star frontman

urges for decades, holding down the low

end for such artists as Steve Cropper, Sister

Hazel, and Phil Vassar. Join in his “touring

therapy” on Twitter @shinybass.