Advanced

Intermediate

• Develop a more fluid jazz time-feel by using hammer-ons and pull-offs.

• Create elegant jazz lead lines.

• Understand how to navigate bebop harmonic passages.

Few figures in jazz history loom as large as Charlie Parker. His pioneering work in the 1940s remains a cornerstone of modern small-ensemble jazz and his playing still sounds fresh today. Parker’s legendary practice regimen combined with his brilliant artistic vision yielded a uniquely personal and virtuosic style. It’s a high bar, but let’s learn some Parker-style jazz language and see how well his style adapts to the fretboard.

We can experience some Charlie Parker greatness by checking out these clips.

Charlie Parker - Now's The Time

Where else to start but the blues? This is Parker’s classic blues tune “Now’s the Time,” which has become essential material for any budding jazzer. His economy of melody has become so codified that the intro to his solo has become a cliché on its own.

Anthropology

There are very few things as exciting as hearing an absolute master tear through a “rhythm changes” tune. Here we have “Anthropology,” which is a medium-up bebop standard. Just listen to how Parker weaves through the cycle of dominant chords on the bridge.

Charlie Parker - All the things you are

Naturally, Parker was also a master of interpreting classic jazz standards. Rhythmically, the melody to “All the Things You Are” is rather vanilla. Check out how Parker embellishes the melody without losing the through line.

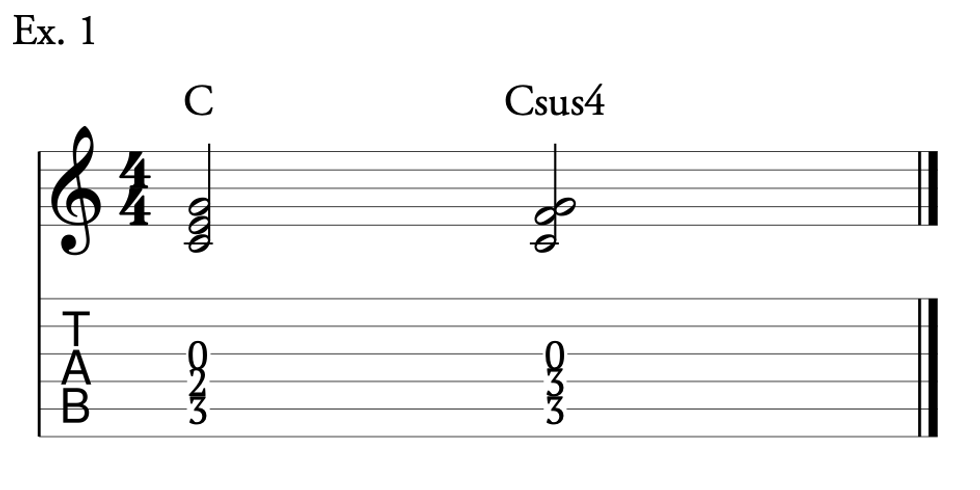

Since Charlie Parker began with the blues let’s start there. There’s a certain irony that bebop guitar players aren’t the bendiest bunch—we often favor slides over bends—but Charlie Parker would frequently bend notes. By changing his embouchure, Parker was able to imbue deep blue inflections in his lines. Ex. 1 is a Bb blues lick that has a few Db to D bends. Unlike typical guitar-based blues playing, these bent notes tend to come from very close to the target note—in other words, you can start with a tiny bit of a pre-bend. Parker would use licks like this in conventional 12-bar settings, but he would also use them in rhythm changes or even standards.

Ex. 1

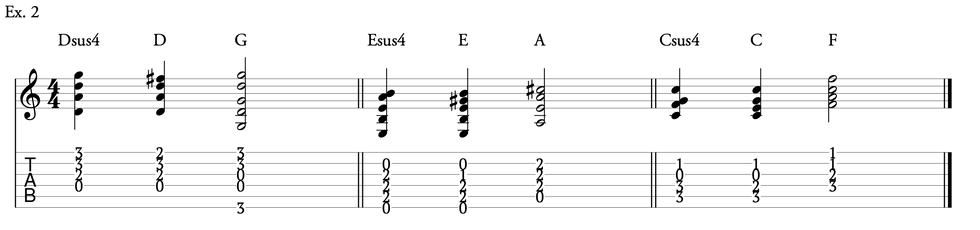

The lick in Ex. 2 is really bluesy and demonstrates a more down-home, Kansas City style. A reverence for blues roots is often present in Parker’s bebop style, especially in his moderate tempo blues tunes. As before, be careful not to overdo the bends—start with a tiny prebend so that you’re close to the goal note. If you’re playing a jazz box with some thick strings, sliding instead of bending is effective as well.

Ex. 2

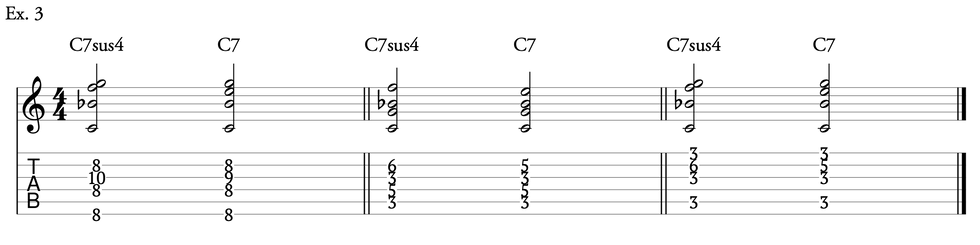

Slurs are integral to creating a convincing Charlie Parker style, on any instrument. We might not be able to capture all of his details (saxophone vs. guitar), but it’s crucial to make the effort. Listen to his original records to notice how he uses legato techniques. This is especially important if you’re playing his compositions in your repertoire—and aren’t we all? It can take some time, but careful study of the music will help you mark up your transcriptions and lead sheets. There is a tendency to slur notes in pairs. Typically, the upbeat is connected to the subsequent downbeat, but Parker isn’t as committed to this approach as later players, such as John Coltrane.

Ex. 3 is a quick little lick over Gm7 where I keep almost entirely within the G Dorian (G–A–Bb–C–D–E–F) scale. Keep an eye on the reverse sweep at the end of the second measure and maintain that rhythmic pulse going through the legato bit at the end.

Ex. 3

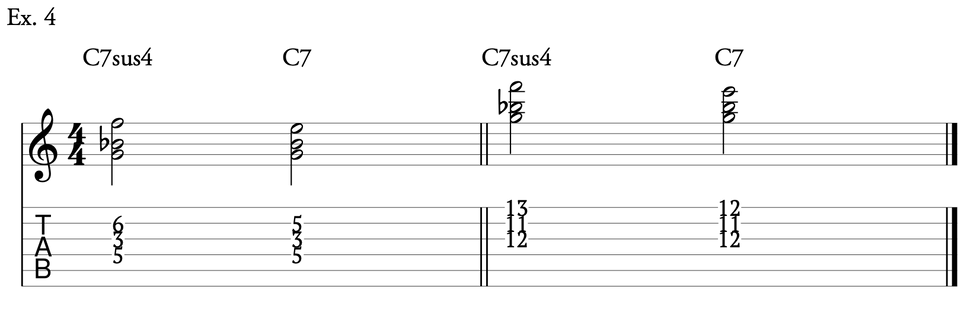

Here’s a typical bebop lick over a IIm7–V7–I in G major (Ex. 4) that incorporates slides and hammer-ons to match Parker’s articulations. We also get to learn some bebop melodic devices here, such as the chromatic embellishment around the note D in the second measure. It’s crucial to get a working knowledge of these non-harmonic tones to establish a convincing bebop vocabulary. Merely applying a chord/scale approach doesn’t cut it here. Follow the notated fingering, as it’s designed to enable a phrasing that matches Parker’s. It might be challenging at first, but the musicality wins out in the end.

Ex. 4

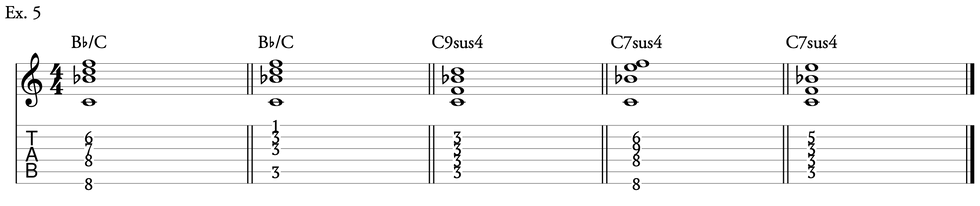

Here’s another IIm7–V7–I in G, similar to the previous line, musically speaking, but fingered in a different way (Ex. 5). The third measure has a bebop rhythmic cliché: an otherwise all-eighth-note line but with a triplet on beat two. This rhythm is super common in Parker’s improvisations and in his original tunes. Invariably, slurs and economy picking are employed to make these triplets work well on guitar. If you are a staunch alternate picker, licks with fingerings like this one will give you a more horn-like sound.

Ex. 5

How about something fast and flashy? Ex. 6 works over Gm7 or C7. Parker played versions of this figure often, so it’s clearly something that he practiced a lot and loved to use as double-time virtuosic line. I should mention, it’s never the same in Parker’s hands. He’ll apply little variations and tweaks, which you can hear as he as he plays this in variety of songs from blues to standards. I’ve incorporated a sweep and single-string legato playing to make it work on guitar.

Ex. 6

Parker’s blues playing was deep and varied. He was equally comfortable on simpler versions of the 12-bar form as well as a variety of more sophisticated versions that he developed as a bebop innovator. (Compare the chord changes on his compositions such as “Now’s the Time” or “Cool Blues” to tunes such as “Au Privave” or “Blues for Alice.”) Ex. 7 shows how even if the rhythm section is playing a basic blues with four measures of the I chord (or a “quick IV” variant) he could play a line that was more harmonically adventurous.

In this case, we hear a melodic idea that implies its own substitute chord changes: a back-cycling idea that would lead to the IV chord in bar 5 (not shown). It’s as if the changes are C7 | Bm7b5 E7 | Am7 D7 | Gm7 C7 rather than four measures of C7.

Ex. 7

The line in Ex. 8 is the final phrase of a C blues (measures 9–12 of the form), in which we hear the typical IIm7-V7 idea followed by a I–VI–II–V turnaround. This is a classic phrasing that highlights upbeat notes, which are picked, sliding into the downbeat notes. There’s a two-fold benefit: easier picking and matching Parker’s phrasing. The turnaround uses chromatically descending arpeggios. Notice the use of an Ebm7 arpeggio on the A7 chord. We can hear this as a loose interpretation of a tritone sub or merely an easy way to get some dissonant upper extension to the chord (including the b5, 13, and b9). The Dm7 gets a purely diatonic treatment while the G7 chord gets a true tritone substitution via the Db arpeggio.

Ex. 8

Ex. 9 works over the beginning of rhythm changes. (“Rhythm Changes” is the name given to any of numerous songs that use the fundamental chord changes from George Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm.” Parker and the beboppers wrote dozens of new melodies and embellished chord changes.) Again, fingerings are not going to seem so intuitive, but the musical expression is worth the effort. This example begins with a diatonic approach in the first measure, but gets more chromatic in the next with the C# over the F7 chord and the smooth chromatic passing tone (Gb) at the end of the measure. There’s a typical descending line in measure 3. You can think of it as implying G7b9 (it does) or as a movement down the C harmonic minor scale.

Ex. 9

Here’s a really long line (Ex. 10) that’s played over the bridge section of rhythm changes. The progression is a sequential cycle of dominant chords. Each chord is the V of the subsequent chord (D7 is V of G, G7 is V of C, and so on.) The D7 idea is mostly diatonic, but there is a b9 in the triplet figure. The G7 also begins diatonically but has a stylistic b9 #9 b9 figure (bar 4) and some chromatic passing tones. This hints at some of the knowledge required for convincing bebop playing: Basic chords and arpeggios must be mastered in order to apply chromaticism and non-harmonic tones.

Ex. 10

The C7 section is interesting because of the note B. This note isn’t a typical choice by beginning players over a C7 chord, but Parker would use it often, but quite judiciously—either as a neighbor tone to the tonic (measure 5) or as a passing tone (bar 6). The use in measure 6 is particularly important. Music theorists after Parker would describe this as the “bebop dominant scale,” which is a form of the Mixolydian mode. In the key of C, instead of the usual seven notes, a B natural is added. This B natural is played as a passing tone on an upbeat so that the tonic (C) and b7 (Bb) can appear as downbeat notes, exactly as done here.

While Parker’s vocabulary doesn’t lay as easily on the fretboard as a Led Zep riff or a Clapton solo, it does offer a glimpse into the mind of a harmonic master. Parker could logically dissect jazz harmony and improvise some of the most engaging and beautiful melodies every created. Even if jazz isn’t your bag, learning a few of these licks will undoubtedly open your eyes, ears, and fingers.