Chops: Intermediate Theory: Advanced Lesson Overview: • Learn about the entire harmonic universe of the melodic minor scale. • Understand how to match the different modes to the appropriate chords. • Develop a deeper understanding of altered dominants. Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson's notation. |

It's interesting how scales develop their names. In particular, what makes Super Locrian super? I'm sure there are a whole host of reasons/theories surrounding that one, but let's save that for another time. Today I want to focus on a different scale that somehow has earned the most admirable of adjectives—the melodic minor scale. The name might lead one to believe that this particular group of notes is the only way to be “melodic" on your instrument. Can we all agree that isn't the case? Cool. Let's move on.

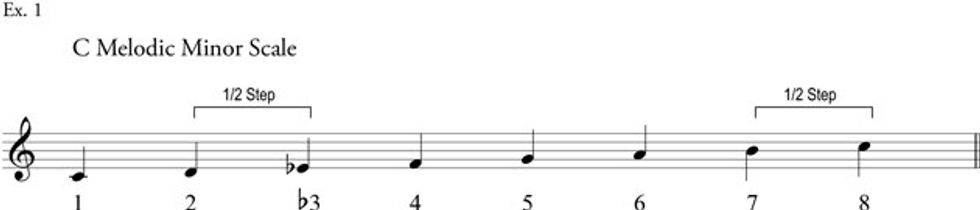

The ascending melodic minor scale is one of the three traditional minor scales. It is constructed with a W–H–W–W–W–W sequence of whole-steps (W) and half-steps (H). In the key of C that would give us C–D–Eb–F–G–A–B or 1–2–b3–4–5–6–7 as shown in Ex. 1. Other ways to wrap you brain around it could be a simple major scale with a b3 or natural minor with raised 6 and 7 scale degrees.

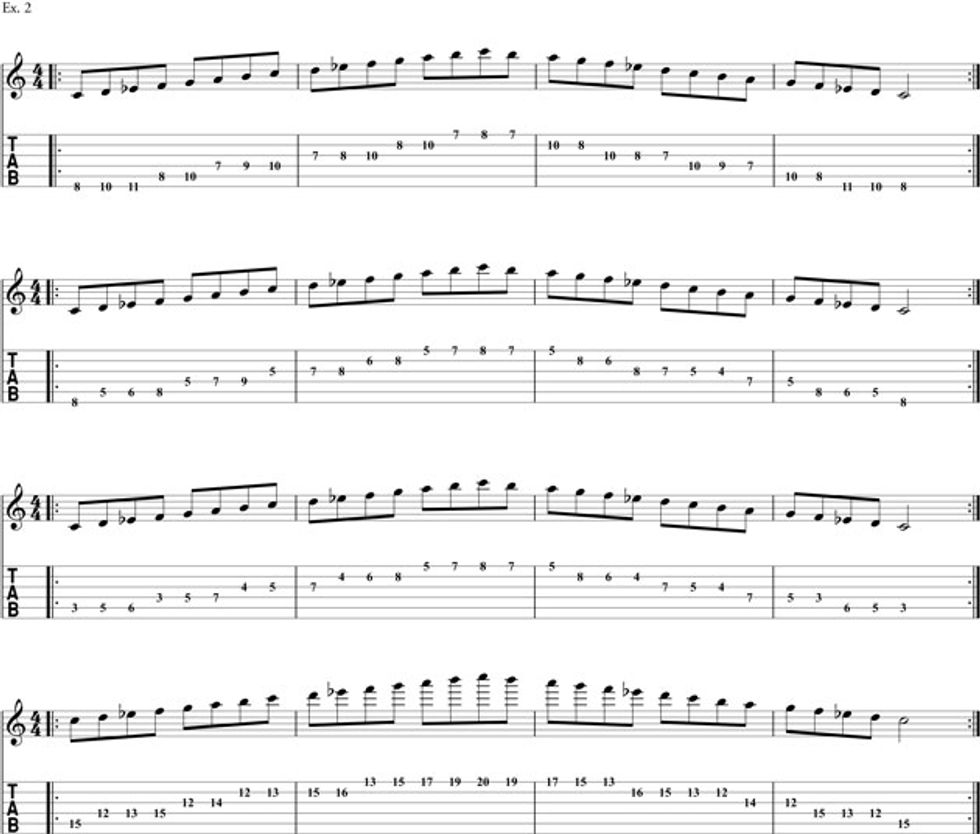

It has a bright sound due to the four consecutive whole-steps in the top half of the scale and is used primarily in jazz to create altered dominant seventh chords and modes that you can't get from the major scale system. Ex. 2 provides you with four common two-octave melodic minor scale patterns. This is an easy way to get the sound of the scale under your fingers and in your ears.

After learning how a scale is built, the next step is to dig into the diatonic thirds, triads, and seventh chords it creates. The better your understanding of the harmony of the scale, the easier it will be to compose and improvise with it. Essentially, figure out what's there, and then figure out how you're going to use it.

In Ex. 3, I've systematically mapped out all the diatonic thirds across five different adjacent string sets. I jumped down the octave when needed, but playing through these will help give you a more horizontal view of the scale. Check out that run of major thirds in the middle—that is the sound of the jazz melodic minor.

Click here for Ex. 3

Next up are the diatonic triads (Ex. 4). This linear view of the triads helps me see how each one is related to one another. The resulting harmonic pattern is Cm–Dm–Ebaug–F–G–Adim–Bdim. Playing through these triads a few times will also help outline the brightness of the scale.

Click here for Ex. 4

What's next? Why, seventh chords of course! In Ex. 5, I wrote out voicings for the chords with roots on the 5th and 6th strings. Here, the harmonic pattern is a bit more complicated: Cm(maj7)–Dm7–Ebmaj7(#5)–F7–G7–Am7b5–Bm7b5. If you haven't seen a m(maj7) chord before, it's simply a minor triad with a natural 7 on top.

Click here for Ex. 5

The previous examples show these dyads and chords lined up and down the neck. You can obviously play the notes together or separately using different rhythms and string patterns. In Ex. 6, Ex. 7, and Ex. 8 I've outlined a few different practice patterns for this scale. I didn't do all the work for you, but I think you will get the gist of it pretty quickly. Over the years I've worked on playing these structures as ascending, descending, and alternating between the two. Obviously, there are other intervals and chord structures that you could work on (and you should), but because most jazz harmony is built by stacking thirds, this is a good place to start. Practicing in this way increase your technical ability, and you'll have something ready to play if you're not inspired by anything else at the moment.

Click here for Ex. 6

Click here for Ex. 7

Click here for Ex. 8

Now, let's dive into the modes of the jazz melodic minor scale. In Ex. 9, I've written out a fingering for each one of the diatonic modes and below I've written out their corresponding formulas.

- C melodic minor 1–2–b3–4–5–6–7

- D Dorian b2 1–b2–b3–4–5–6–b7

- Eb Lydian augmented 1–2–3–#4–#5–6–7

- F Lydian dominant 1–2–3–#4–5–6–b7

- G Mixolydian b6 1–2–3–4–5–b6–b7

- A Locrian #2 1–2–b3–4–b5–b6–b7

- B Super Locrian 1–b2–b3–b4–b5–b6–b7

Click here for Ex. 9

Suppose you need to find the parent key of A Lydian dominant. Simply find the melodic minor scale that has an A as the fourth note. Spoiler: It's E melodic minor. In Ex. 10, each mode of the jazz melodic minor scale is played in order starting on C. Playing them from the same root allows you to actually hear how different each mode sounds. When played diatonically, it's easy to miss their individual characteristics. Memorizing the order of the modes will help you find the parent key of any single melodic minor mode.

Click here for Ex. 10

The next step, of course, is figuring out how and where to use these modes. You have to think about chord type and chord function, just like the modes of any other scale. The melodic minor scale can be used over any min(maj7), m6, or any chord that functions as the tonic in a minor key. That means if you're playing a blues in C minor, you can use the C melodic minor scale. Check out Ex. 11 to hear what this mode sounds like over a simple Im–V progression in C minor.

Click here for Ex. 11

The second mode, Dorian b2 can be used over a IIm7 chord. It's a darker sound compared to the Dorian mode due to the b2. In Ex. 12, I'm playing the A Dorian b2 (G melodic minor) over an Am13 vamp, focusing on triads and thirds to bring to the 13th and b2 sound of the mode.

Click here for Ex. 12

If the Lydian mode is bright enough for you, then get into the Lydian augmented scale, the third mode of melodic minor. Ex. 13 uses the E Lydian Augmented (C# melodic minor) over a G#/E to F#/E vamp. I'm still utilizing thirds and triads to get the sound of the mode, but also targeting chord tones of Emaj7(#5).

Click here for Ex. 13

Jumping ahead to Locrian #2, this mode is used over m7(b5) chords to get a slightly brighter half-diminished sound with a little more tension. Ex. 14 uses the F# Locrian #2 mode (A melodic minor) over an F#m7(b5) vamp, exploring the #2 sound in a couple different positions.

Click here for Ex. 14

The next three examples explore dominant seventh sounds and each example is over a IIm7–V–I–VIm progression in D major. First up is Lydian dominant in Ex. 15. When confronted with a 7(#11) chord, this is the mode to use. It's almost identical to Mixolydian, but with a raised fourth scale degree. Over the V chord, I'm playing A Lydian dominant (E melodic minor), and B Lydian dominant (F# melodic minor) over the VI chord.

Click here for Ex. 15

In Ex. 16 we dive into Mixolydian b6. Again, it's almost identical to Mixolydian but with a flatted 6th scale degree. Over the V chord I'm playing A Mixolydian b6 (D melodic minor) and over the VI I'm using B Mixolydian b6 (E melodic minor).

Click here for Ex. 16

Last but not least is Super Locrian. Even though this mode builds a m7(b5) chord, it is often used over a dominant chord to get all the altered tones (b9, #9, b5, #5), hence the “altered scale" name. It's also known as the diminished whole tone scale because it begins like a half-whole diminished scale and ends with whole tones. In Ex. 17, I'm playing A Super Locrian (Bb Melodic Minor) over the V chord and B Super Locrian (C Melodic Minor) over the VI chord.

Click here for Ex. 17

The jazz melodic minor scale can be used over all the seventh chords found in the major scale system. It will add new color tones and tension to your soloing and chord voicings. You could potentially substitute a mode of the jazz melodic minor over every seventh chord in a jazz standard and create an alternate diatonic universe. Obviously, that would eat up a lot of clock time in your weekly schedule, but in the meantime, you can add these new flavors to your favorite lines and come up with a brand new you. Enjoy!