Somewhere around 3 a.m., a young guitarist awoke wide-eyed and elated from a cannabis-fueled dream. It was the summer of love—a time when anything seemed possible—and his dream-state adventure had led to a powerful revelation he was sure would shake belief systems into dust. Instinctively, he grabbed a pencil and paper from the nightstand, jotted down his epiphany, then rolled over and fell into the most satisfying and peaceful sleep of his life. The next morning he awoke with excitement, certain that his world was about to change forever. He reached for the note he’d left for himself, unfolded it, and read the words: “I feel funny.”

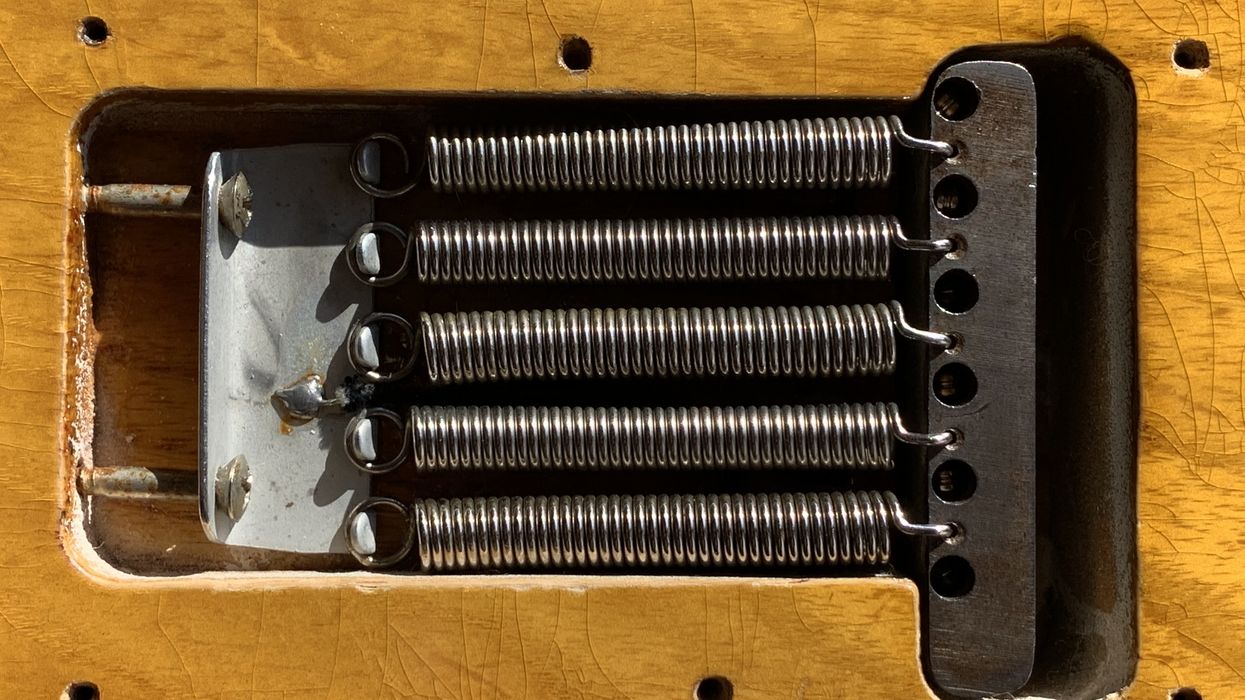

I think of this story when I see guitar designs that attempt to push the envelope of what is considered mainstream. Sometimes they work, other times not so much. Was the builder high? No doubt there have been groundbreaking changes in the electric guitar world. The humbucking pickup, the Flying V, the Stratocaster, wireless, the Floyd Rose tremolo, and DSP come easily to mind. For the most part the guitar marketplace was pretty staid up until those times, but Fender had fired the first shot in a space-race to capture a brave new guitar market that didn’t yet exist.

That isn’t to say that there hadn’t been advances in construction or presentation—there obviously had. Although the Telecaster presaged what was soon to come and had the attention of guitar manufacturers, it really wasn’t taken all too seriously. It’s arguable that the P-bass in 1951 may have been a wakeup call. Gibson and the old guard responded with 6-string solidbody variants of their own, but they were mostly scaled-down versions of their previous products in the classic “violin” mold. With the arrival of the Strat, things got real. And so, the first electric guitars of the modern era were born and fledged out into the world. It was a lukewarm reception at first.

“Valeno, Kramer, and Travis Bean married wood and aluminum, while Bunker and Steinberger broke the mold completely.”

This is a tale that has been told almost as many times as builders have cloned the Stratocaster. Yet as more and more people became interested in electric guitar, boosted no doubt by the arrival of the Beach Boys and the Beatles, the more experimental the design world became. It was clear that fashion was the ticket as much as mechanical or electrical innovation. The emphasis on the shape of a headstock and body as well as color became the new design canvas. Who could be the far-out grooviest? It hasn’t slowed down since.

As always, things settled into routine again. Paul Reed Smith wanted to morph two or more of the most popular shapes in electric guitar history. To his credit, he split the difference almost perfectly. Others, like John Suhr and Tom Anderson, sought to refine the Fullerton blueprint with admirable success, while Bernie Rico created a fever dream of wild shapes, string arrangement, and electronics. Many others gave it their best shot: Valeno, Kramer, and Travis Bean married wood and aluminum, while Bunker and Steinberger broke the mold completely. At Hamer, we looked to the vintage past for our future. Then things got stale again and everything seemed to be a rehash. It seems like we’ve been in a holding pattern of mix and match for a while now. Sure, playability has never been better, and choices are abundant beyond anything I’d ever imagined. Things are good.

As the guitar world becomes all the more deep and wide, with almost every neighborhood hosting a custom guitar maker, it becomes harder and harder to come up with something new. So, like every fashion house on earth, the name of the game is to dig into the past and blend parts and materials in the hope of catching a little lightning in a bottle. Once you realize that as long as the nut, fretboard, and bridge stay in the correct and same relationship, anything else can be changed. Like Legos, you can build your dream guitar by swapping influences—mixing and matching until you have that earth-shaking, world-beating gumbo that puts you on the map. Or not.

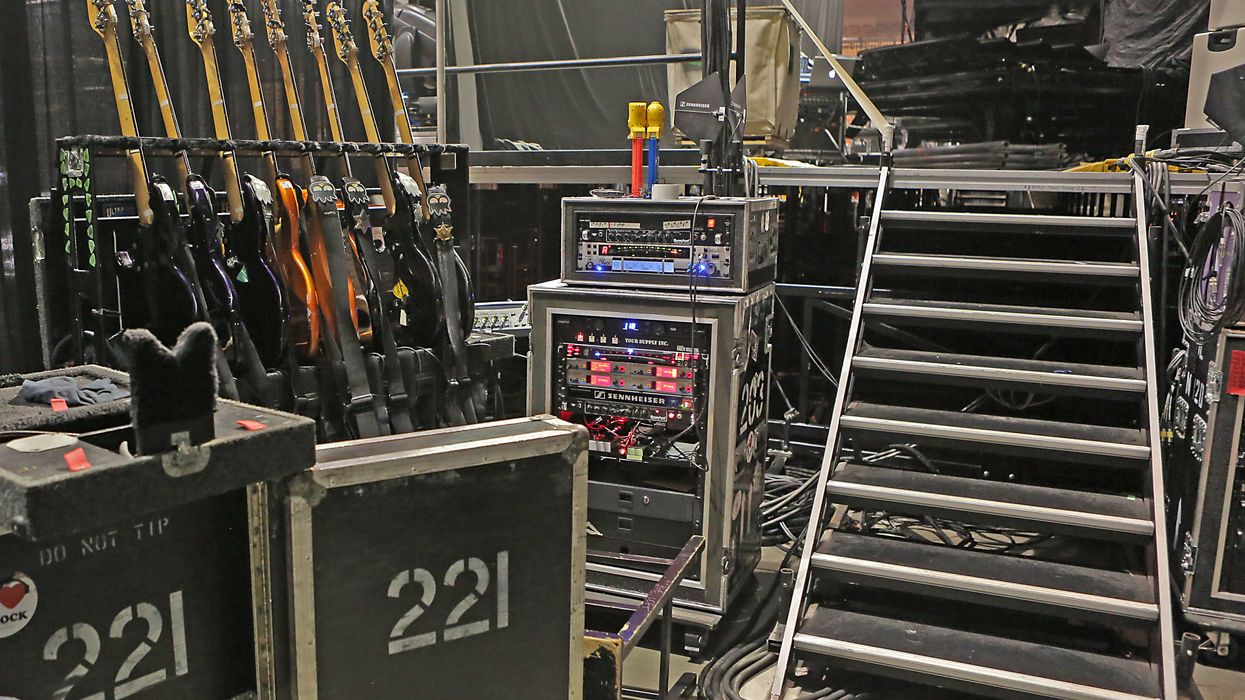

I’m not complaining, and neither should you. I constantly see new takes on old ideas and think, “Why didn’t I think of that?” You can now buy a $300 guitar that can make it through a stadium gig—at least once or twice. The old guitars have the romance and the new guitars have the muscle. I still look at Reverb and wish I had more money and space. Occasionally, I build out of my comfort zone but don’t worry about finding that life-changing thunderbolt. I also suggest avoiding ideas that are funny in the moment. And that brings us right back to that piece of paper on the nightstand.