In a world where Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube are literally saturated with teens and younger kids who have bass chops capable of scaring most grown bassists into an early grave, the prospects of ever becoming the next to achieve Jameson- or Jaco-level status seem bleak. Last week, a friend sent me a video of a very young girl ripping through John Coltrane’s “Giant Steps” solo as Coltrane played along in the background. She sounded great, and so did Coltrane! I, too, learned that solo in my late teens, so I know firsthand how hard it is to play up to speed, but she did it with a smile and made it look easy.

When I first began learning the instrument at 14 (I’m still learning), like most young people I was attracted to shiny things. For me, that particular shiny thing was Mark King of Level 42’s otherworldly ability to slap a bass at what seemed like the speed of light. His amazing technique was indeed so shiny that it was able to pull me from the guitar to the bass. I spent what seemed like an eternity (probably a year in adult years) learning how to slap really fast, and for my first two years as a bass player, slap was all I did!

Photo by Dimitri Louis

Many years later, I learned something else that was difficult to grasp, which becomes rarer by the day: “The bass” is not only an instrument, clef, or stave (nearer the bottom of most scores), it’s more importantly a role, or more aptly put, a function essential to almost all modern music. It’s the root of it all. Bass plays a role that forms a unique bridge betwixt rhythm, harmony, melody, and groove. The greatest bassists have all understood this fact in their own ways, and many of these masters never lusted for, and understood that they did not require, Paganini-like gymnastic mastery in the lower hertz. Don’t get me wrong … I personally love and have even pursued technical mastery. Thus, I’m a lover of great bass, sax, and whatever else solos. But those two things—soloing and becoming a technician—are not necessarily immediately related to the “bass function.”

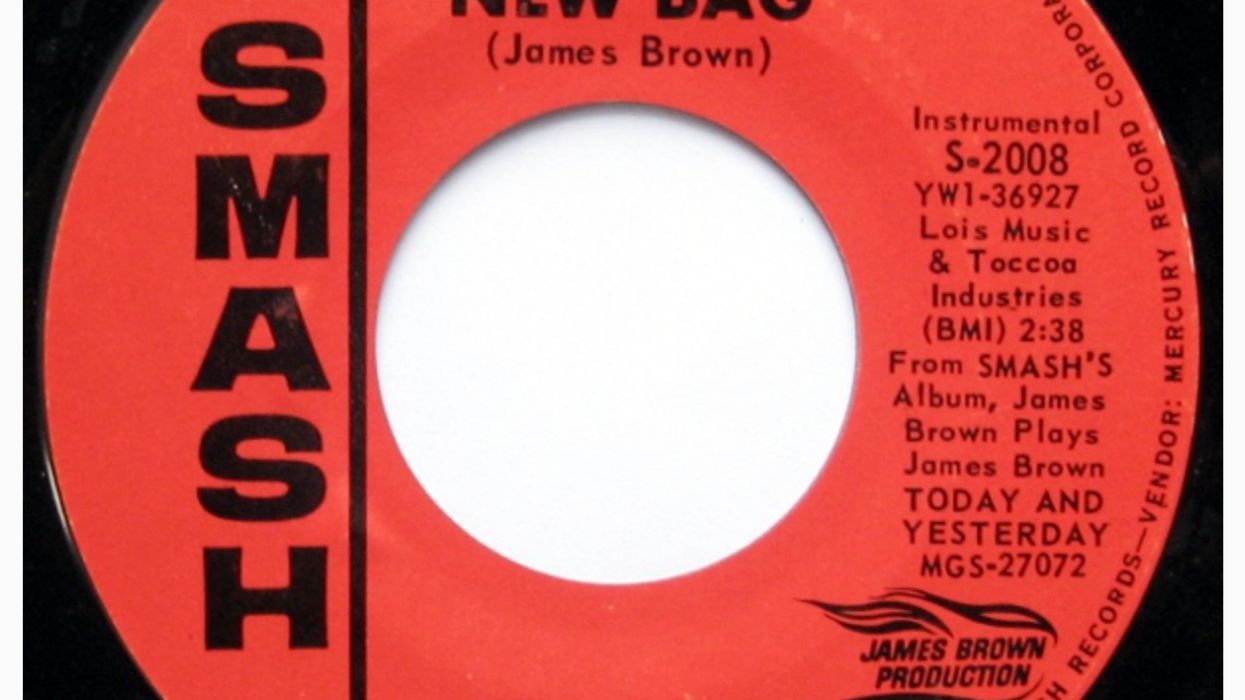

As we go back in time to the root, the number of players who focused on function over flashy technique, and support over soloing seems to increase. I soon learned there was more to bass than slapping. (I also learned that slapping—though not quite at the speed of light—went back decades before Mark King.) I had no idea of the long and storied history of bass, and how this fit into the African American musical canon, which included blues, jazz, gospel, rock ’n’ roll, R&B, funk, soul, disco, hip-hop, house, and a seemingly never-ending procession of subgenres—which is to say most American music.

“The bass” is not only an instrument, clef, or stave (nearer the bottom of most scores), it’s more importantly a role, or more aptly put, a function essential to almost all modern music.

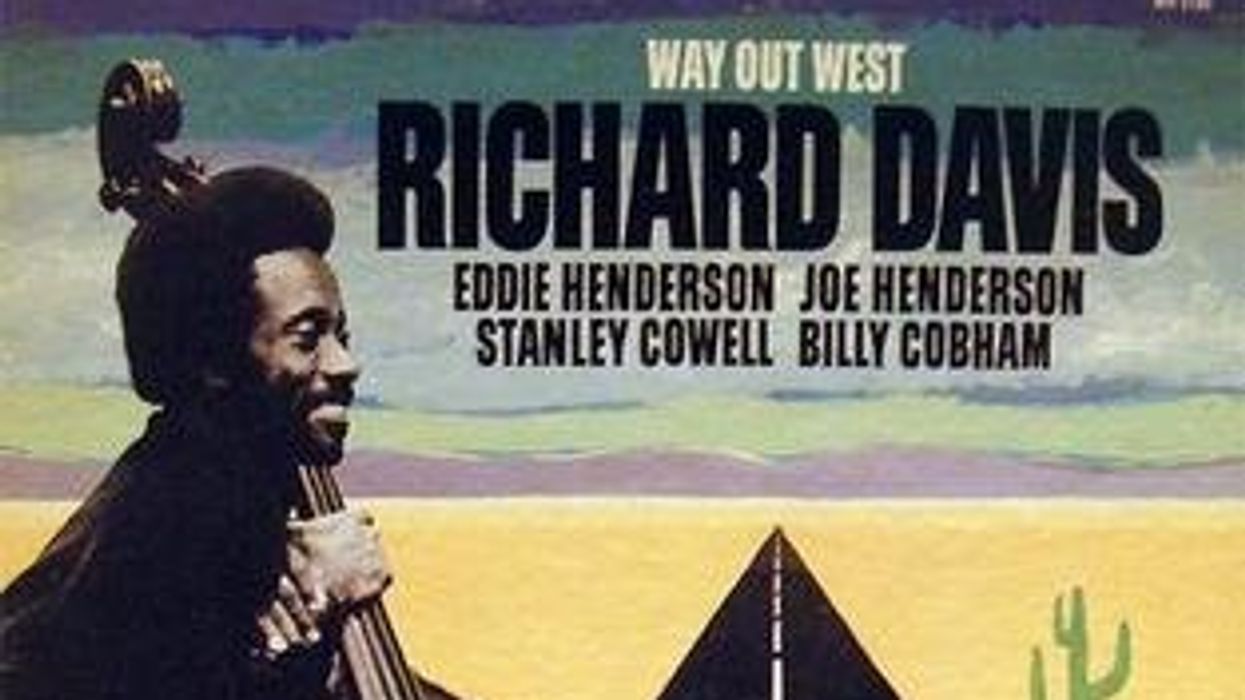

Eventually, with the help of American mentors Rich Nichols and Steve Coleman, my quest to understand bass, and music in general, would lead me to Philadelphia (and, later, to Harlem, NYC). Through Rich, a Philly native who also happened to be manager and patriarch of the Roots, I became an integral part of the exciting mix of music happening in Philadelphia in the late ’90s and 2000s. This formed the foundation of my education as a producer and provided opportunities for me to produce records for many well-known names in hip-hop, soul, funk, pop, etc. Through Steve—a Chicago native who moved to NYC in the ’70s and was responsible for creating the M-Base movement, which many consider to be the font of at least 50 percent of today’s NYC jazz scene—I learned about America’s rich jazz tradition. Between decades of touring, hanging out listening to much older musicians, and the wealth of things that Steve and others taught me directly, this formed the foundation of my music education. It gave me the tools to begin the Creative Music Program, which served as a foundation for many young creative musicians coming out of Philadelphia.

Philadelphia is home to some of America’s greatest bass legends, and it was once I moved to the city that I met Jymie Merritt, a relatively unsung hero of the bass, but a legend if there ever was one. Not only was Jymie a master of the upright, but he was also an early pioneer of the electric bass within jazz, and a fantastic composer. I met so many other great American bassists who, like me, continue a tradition and culture which stretches all the way back to the days of tubas, wash tubs, and broomsticks—a time somewhere between the abolition of slavery and Louis Armstrong first meeting the horn. These are players such as Henry Grimes, Stanley Clarke, Charles Fambrough, Victor Bailey, Jamaaladeen Tacuma, Reggie Workman, Christian McBride, Gerald Veasley, Reggie Washington, Anthony Jackson, Matt Garrison, Rich Brown, Richard Bona, and many others.

Stay tuned! I’ll surely be focusing on some of these and many farther afield subjects in future Root of It All columns.