The arena-filling rockers cheekily exude excess with a cavalcade of signature gear and some custom creations—including a pink number that made some see red.

Musical acts currently filling arenas fall into a few categories: pop, electronic, country, and legacy. The notion of modern or contemporary rock bands packing enormo-domes feels like a fossil, but don’t tell that to platinum-selling Shinedown, who’s been packing thousands-of-seats houses for years.

The group was founded by vocalist Brent Smith in 2001, after his previous band, Dreve, disbanded). He enlisted Jasin Todd (guitarist), Brad Stewart (bass), and Barry Kerch (drums). Zach Myers joined the fold in 2005 (as a touring member). He and current bassist Eric Bass (no joke) first earned album credits with 2008’s smash The Sound of Madness. (Rig Rundown alumnus Nick Perri was a short-time member of Shinedown and earned lead guitar credits on TSOM before fully handing over the 6-string reins to Myers.)

The quartet’s ability to fuse post-grunge pyrotechnics, four-on-the-floor rockers, and glossy, arms-in-the-air anthems, and their dynamic acoustic performances, have earned them 17 No. 1 hits on Billboard’s Mainstream Rock chart. (If you include the other Billboard charts, they’ve got three more.) They also have three platinum albums (three more are certified gold in the U.S.), and six additional platinum singles. If guitar truly is in a slump in pop culture and the mainstream, somebody forgot to tell Shinedown.

When PG’s Chris Kies first talked tone tools with Myers and Bass in 2013, they had some gear, and even some cool signature stuff. But this time, the war chest was on another level. Before their May 4 headline show at Nashville’s Bridgestone Arena, supporting their new, seventh album, Planet Zero, the duo flexed their rockstar credentials and carted out 40-plus instruments. Myers contends he uses every one of his guitars on a nightly basis. And Bass details his signature line of Prestige basses, which incorporate an ingenious thumb rest. Myers also shows off an irreplaceable PRS created by the late American fashion designer and entrepreneur Virgil Abloh (Off-White), and he explains how a custom-painted Silver Sky earned him some serious eye rolls and scoffs. Plus, their techs break down the power and might that help them rock the rafters.

Brought to you by D’Addario XS Electric Strings.

The Pink Problem

If you’re a fan of PRS, you know they don’t offer relic’d instruments. So, Zach Myers took matters into his own hands and had his personal Silver Sky (originally white) refinished in shell pink by McLoughlin Guitars before the custom distressor gave it their “ultimate” treatment—one that equates to a snake shedding its skin. Myers had no idea Mr. Mayer and PRS were going to release additional colors for his Strat-style signature. Needless to say, some people weren’t happy with Zach crashing the pink party, but he loves the guitar, loves John, and even admits in the video that the custom relic is an homage to Mayer’s black 2004 Custom Shop Strat. He plays it every night for the song “Monsters.”

He uses .011–.049 strings (S.I.T. and Elixirs) on standard-tuned guitars, and for lower tunings he typically rocks with .011–.052 sets. And as you’ll see in the video, his tech Drew Foppe throws curveballs at him by putting various sized, textured, and gauged picks on his guitars.

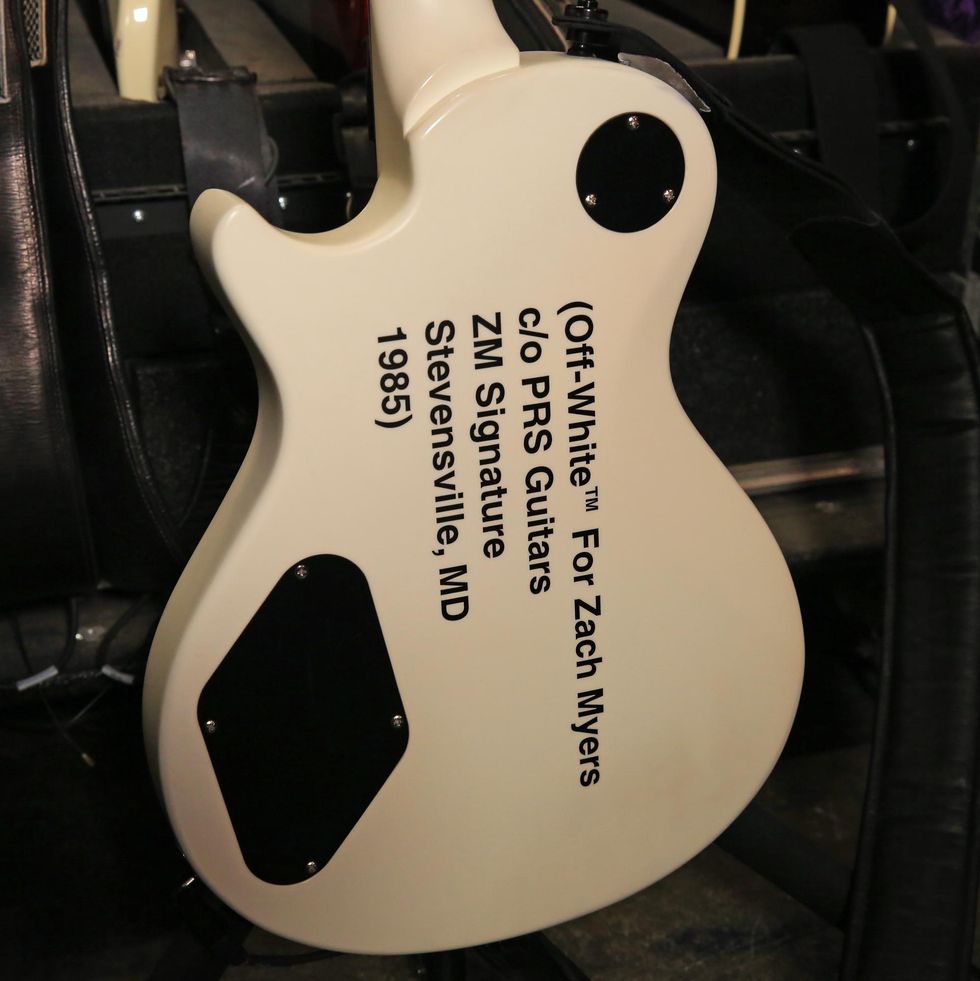

Off-White

Myers is a big sneakerhead and follower of fashion. He was lucky enough to have designer Virgil Abloh customize one of his PRS SE Zach Myers signatures before the fashion icon’s untimely passing in 2021. (Abloh reached unparalleled zeniths as CEO of the Milan-based Off-White outfit and artistic director of Louis Vuitton’s menswear—the first person of African descent to earn such a title.) As you can see, within his Off-White brand Abloh would utilize obvious labels for things (“switch” and “guitar”). He always incorporated one element of orange in his designs, and the video game button is a killswitch. The axe gets played on “Cut the Cord.”

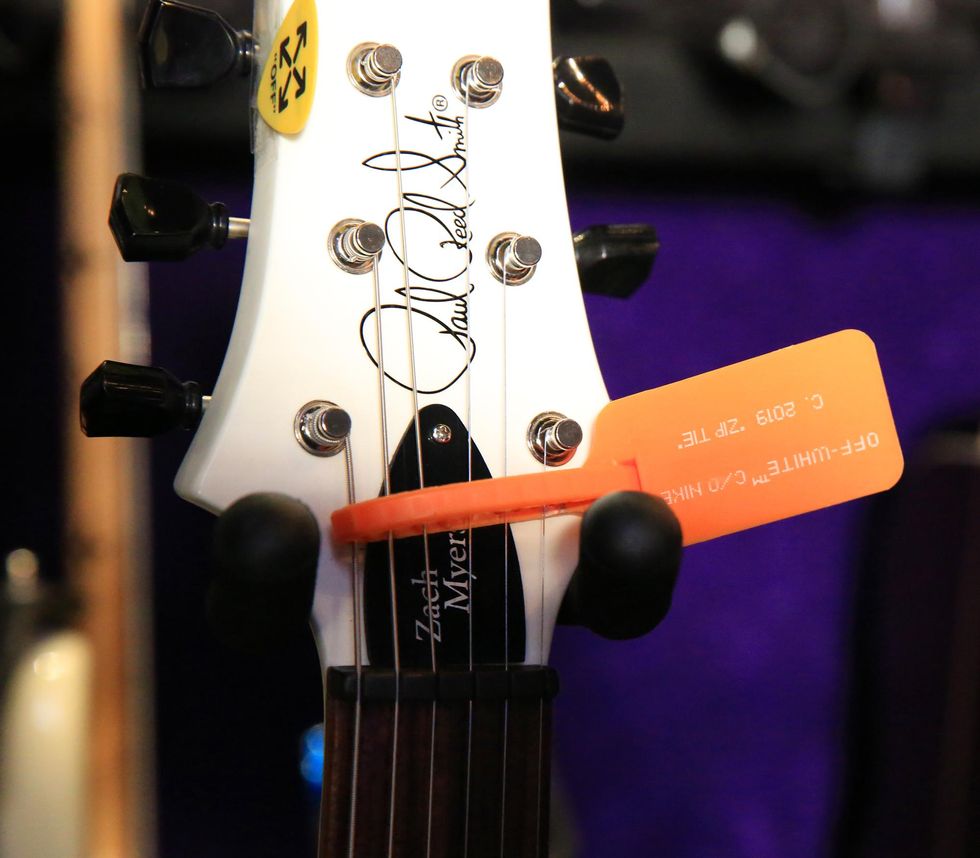

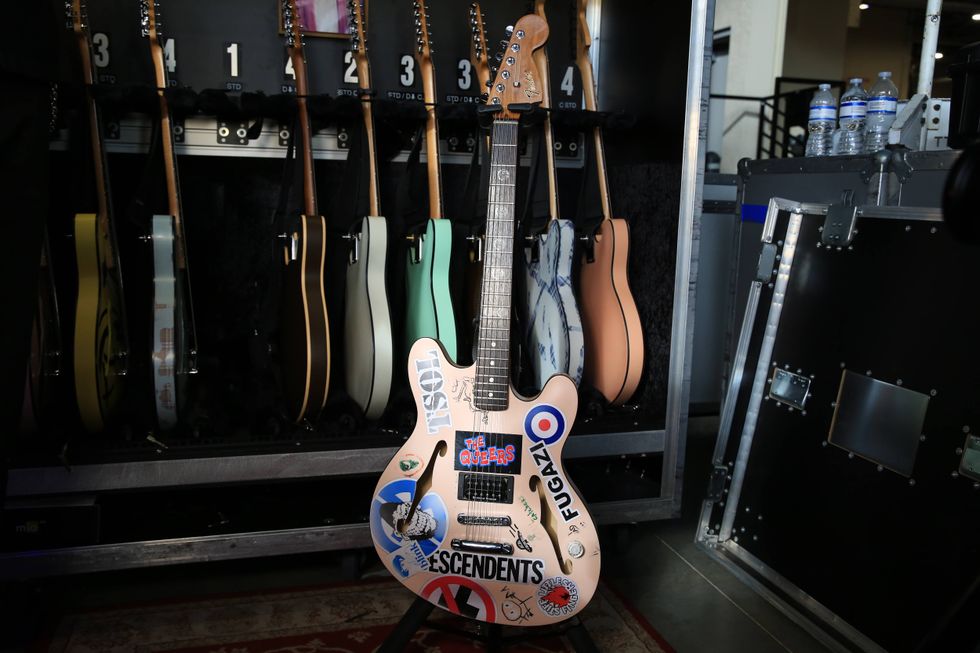

Tagged

Here, you can see Off-White’s signature tag on Myers’ signature headstock.

Branding

You can’t argue that anyone would mistake Off-White’s work.

I Spy

Here’s another one of Zach’s SE chambered semi-hollow signatures that was done up by L.A. street artist Joshua Vides, who has worked with Fendi, Mercedes-Benz, and Major League Baseball. The black-and-white color scheme gives a very Spy-vs.-Spy vibe, featured forever in Mad.

The Cat’s Meow

This is a PRS Private Stock Paul’s 85 that gets busted out for “Get Up” and rides in a “sort of” double drop-D tuning (both E strings tuned down to D), with custom-gauge strings (.010–.049). This run of Private Stocks features an African mahogany body, figured maple top, a dark Peruvian mahogany neck, and a Honduran rosewood fretboard, and is finished in a striking electric tiger glow.

An Extra Pair

Here is Zach’s PRS DW CE 24 Floyd—one of his two touring guitars with 24 frets. It’s a signature model for Rig Rundown pal Dustie Waring of Between the Buried and Me and comes stock with PRS’ hottest ceramic pickups. It gets stage time for “How Did You Love.”

Sweet Tea

This is one of Zach’s latest additions: a PRS 594 McCarty used on “The Saints of Violence.” Zach puts it in coil-tap mode, and Foppe rewired the guitar from LP-style to a more familiar PRS-style setup.

Santana Myers Model

When you have Paul Reed Smith on speed dial, you can get this made. Myers had the silky-looking Santana model transformed into a semi-hollow matching his SE signature format. This gets brought out for the fan favorite “Second Chance.”

Elephant on the Fretboard

Paying homage to his dear friend and Shinedown singer, Brent Smith, Myers had PRS add an inlay of elephants. (The largest existing land animal is Smith’s favorite beast.)

Old Friend

This might be one of Zach’s oldest touring guitars currently out with Shinedown. The PRS NF3 gets some action during “45” and never can be replaced, since its sound is so unique, with 57/08 Narrowfield pickups that he says are unlike any others in his live arsenal.

I’ve Got a Mira by the Tail

If you caught our 2013 episode with Shinedown, you’ll recognize this Buck Owens-inspired Mira with 57/08 humbuckers that he gets busy with on “Unity.”

Workhorse

It might be a stretch to label this Martin J-40 with such a name, seeing it’s only featured on two songs (“Simple Man” and “Daylight”). But most of the guitars in this Rig Rundown only get used for one jam per night. The J-40 takes Elixirs (.011–.052).

Blue Jean

Here’s a custom take on the earliest versions of Zach’s PRS signatures that gets the spotlight for “Enemies.” It is tuned down a whole step, to D standard. Note the distinctive bright hue on the guitar’s side, by the horn.

Scorpion

This custom McCarty 594 pays its dues for the song “Bully.” It takes an .011–.052 set and rumbles in C# tuning.

Maple, Maple, Maple!

This McCarty model is made entirely of maple and makes hay on the song “Save Me.”

More Maple?!

Another all-maple McCarty, but this is chambered and struts out for “State of My Head.”

Zach’s Blues

Here’s the latest incarnation of Zach Myers’ SE signature that debuted in early 2021. Subtle updates include a lusher “Myers Blue” (he admits it’s pretty pretentious) finish, black bobbins on the pickups, black tuning pegs, and a matching headstock veneer. This blue bombshell makes an appearance for “Fly from the Inside.” And whenever Myers sees a kid having the time of his life at a Shinedown show, he’ll call on Foppe to bring out one of his new signature models and he’ll gift it to the youngster. How cool is that?!

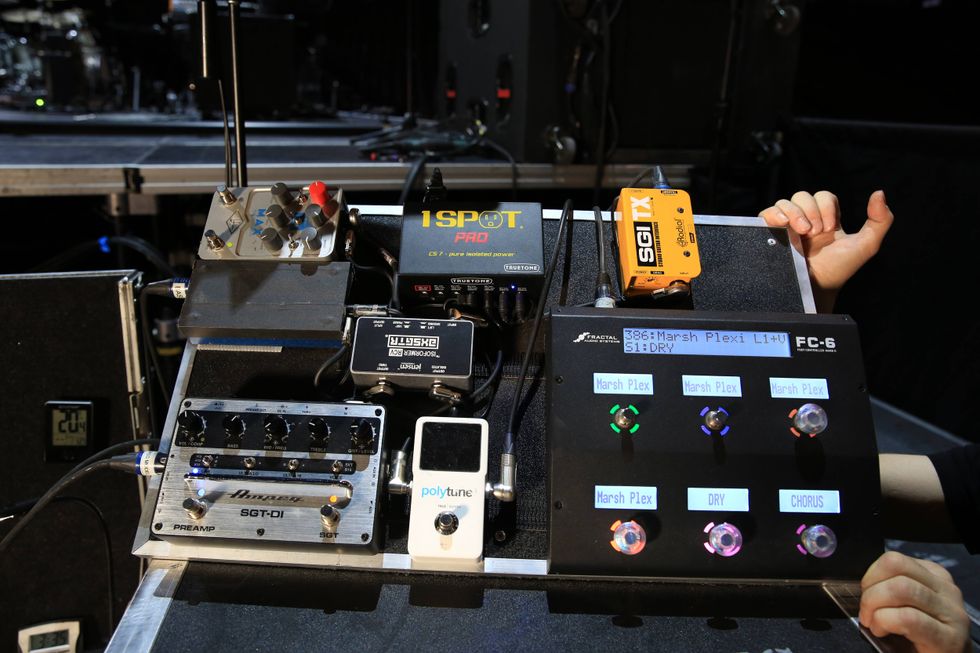

Rack Control to Major Drew

With a rig this big, doing this much, in front of thousands, you need a primed pilot at mission control. And lucky for Myers, tech Drew Foppe is up to the task. Everything starts at the Fractal Audio Axe-Fx IIIs. (There’s a main and a backup.) There are four channels of Shure UR4D+ wireless units (three for electric and one for acoustic). From there they run an AES digital out to the Antelope Audio Trinity Master Clock and Antelope Audio 10MX Rubidium Atomic Clock. This helps fatten the fully stereo, digital rig by converting it to analog and then sending it back. After that they use IRs off the Axe-Fx (left and right) into a pair of Neve DIs that then feed a Fryette G-2502-S Two/Fifty/Two Stereo Power Amplifier. (There’s another for backup.) And finally, they send parallel signals to two ISO cabs and two Universal Audio OX Amp Top Box reactive load boxes (both left and rights). Altogether, there are eight channels of guitar.

Zach Attack

While Drew oversees the main operation, Zach still has some control at his toes. He’s got a Dunlop MC404 CAE Wah, DigiTech Whammy V, Ernie Ball 40th Anniversary Volume Pedal, and the Fractal Audio FC-6 Foot Controller. Peeking out from the mini board is a Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2 Plus, giving life to these effects units.

Bass’ Bass

Since our last gear chat, Eric Bass teamed up with Prestige Guitars to make a childhood dream come true. A memory that’s stuck with him since he was a young musician was how cool Stone Temple Pilots’ bassist Robert DeLeo looked harnessing a Telecaster bass. So, when Prestige asked for some of his ideas, he knew where to start. The slightly offset double-cutaway has a solid ash body, a 1-piece, hard rock maple neck (with a bolt-on connection), and a pau ferro fretboard. The neck has a slim C-shape (similar to a J-style bass). There’s a Seymour Duncan SCPB-3 Quarter Pound pickup and Hipshot hardware (4-string A-Style bridge and HB-7 tuning machines). One thing that won’t show up in the spec sheet is the sneaky thumb rest that has a small ‘E’ on it. It’s a design inspired by the top of a humbucker, because Eric was so used to resting his thumb atop of a ’bucker that he was a bit lost without it. They initially tried standard flat thumb rests, but Bass was inclined to use the curved pocket on top of the humbucker as leverage to throw around the instrument onstage. Bass’ personal instruments have brass nuts, whereas the production models will have bone.

Bass uses three or four tunings each night that will include standard, drop D, C#, and drop C. For standard and D, he’ll go with his set of signature S.I.T. Strings (.050–.110), and for the lower tunings he extends the low string to a .115.

Three on the Tree

Here’s the sleek reverse headstock for Eric Bass’ signature models.

Go for the Gold

This was the second prototype for Bass’ signature. It featured a belly-cut contour that he ultimately did away with. He prefers the bigger slab-body style and the dual edges allow for some sick double binding seen on the production models.

Kerns the Conspirator

Bass isn’t afraid to get down on someone else’s signature cruiser, and he does so each night with the Prestige Todd Kerns Anti-Star 4-string. (Kerns is in Slash Featuring Myles Kennedy and the Conspirators and fronts Canadian rock band Age of Electric.) This one has a 7-piece mahogany/walnut body, mahogany neck, and ebony fretboard, and comes off the rack with Seymour Duncan USA Todd Kerns pickups.

Kerncidentally

Here’s Bass’ signature Prestige sporting a set of Todd Kern’s Seymour Duncan pickups.

Show and Tell

Eric sent a few basses over to Relic Guitars The Hague in Netherlands so they could mess them up in the most beautiful way possible. He gave them some instruction and creative carte blanche.

And here’s a close-up of the artwork.

Here’s Looking at You, Bass

Here’s another example of the handiwork happening inside Relic Guitars The Hague. The inspiration is the oil painting “Girl with a Pearl Earring” by Johannes Vermeer, from 1665.

Nash Bash

This Nash PB52 preceded his Prestige signature, but you can see how he got the wheels turning for mapping out his own instrument. Bass affectionately calls this one “Grimace.”

Move It On Over

Each night, Bass takes over 6-string duties and makes music with this Prestige Legacy OM.

Refrigerator Rig

Tech extraordinaire Jeramy “Hoogie” Donais helped create this efficient fridge-sized setup for Bass. As he explains it, the Prestige basses hit the Shure UR4D+ wireless units (similar to Myers, he has three channels for bass and a channel for acoustic), then a Neve DI, and into a Radial JX44 signal manager (he does have a 100' cable for backup but hasn’t used it in his eight years with Shinedown) that feeds it into an Ampeg SVT-7 Pro for clean tone (with an extra for backup).

Tube Tone with Teeth

The right-hand rack features a pair of Mojotone Deacon (inspired by the sound of Queen bassist John Deacon) 50W heads that run on a pair of KT66 power tubes. One beast gets engaged for Shinedown’s heavier songs and one sits below as a reserve.

Noise? What Noise?!

To help keep the rig calm and quiet, Bass has a Revv G8 Noise Gate to remove any unwanted buzz and hiss.

Eric Bass’ Gas Station

Onstage sits Bass’ pedalboard that includes a Dunlop 105Q Cry Baby Bass wah, a DigiTech Bass Whammy, and an MXR M299 Carbon Copy Mini Analog Delay. The ‘Gas’ switch engages the Mojotone Deacon, a Radial SGI-44 1-channel Studio Guitar Interface connects with his rackmount JX44, the BossTU-3W Waza Craft Chromatic Tuner keeps his instruments in check, and a hidden Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2 Plus feeds juice to everything.

![Rig Rundown: Shinedown's Zach Myers and Eric Bass [2022]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/rig-rundown-shinedown-s-zach-myers-eric-bass-2022.jpg?id=29822141&width=1200&height=675)

![Rig Rundown: John 5 [2026]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62681883&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C45%2C0%2C45)