If you play electric guitar, you don't just play electric guitar. You also play the amplifier—because that's what ultimately projects the sound. In fact, you're playing a myriad of components in the physical and electronic chain between your fingers and the sound waves emanating from your speakers. Every one of those components has an effect on your tone, which means you could easily argue that your amplifier is the most complex tone-producing element in your signal path.

Here we're going to revel in the nuance, the history, and the dedication of the people behind five of the world's most celebrated amplifiers—a quintet of classic boxes whose importance in the pantheon of guitar tones cannot be overstated. Their definitive sonics have shaped music as we know it over the last half century, and by extension their designs have paved the evolutionary path of amplifier development past, present, and future.

Did we leave any amps out? Sure—how could we not? There's no shortage of ways for imaginative guitarists to get the right tones for the occasion with all sorts of gear. What matters most is creativity, passion, and attitude—even iconic gear doesn't make magic happen automatically. But the beauty of the designs chronicled here is how they defied tradition—even if just a smidgen—and turned unusual simplicity into uncommonly great tones for adventurous players to use creatively.

So, yes, winnowing the list down to five was tricky. But read on and you'll see how these game-changing amplifiers helped create the sounds that made us want to play guitar in the first place. We aren't discussing them in hierarchical terms of “best" or “most influential"—each is too unique and empowering for such trifling. Instead, we'll discuss the amps chronologically, based on the year each design was introduced.

Vox AC30

The sound of the Vox AC30 isn't just permanently etched in the minds of rock 'n' roll fans everywhere. Its diamond-pattern grille cloth, seen as backdrop in innumerable photos of the Beatles and countless bands from the British Invasion up to the present, is permanently etched on our retinas. It's a ubiquitous design used by such notable players as the Kinks' Dave Davies, Rory Gallagher, U2's the Edge, Peter Buck of R.E.M., and Queen's Brian May.

The AC30 got its start in the 1950s. Tom Jennings founded Jennings Organ Company, which produced the Univox—a “piano accordion" that incorporated a three-octave keyboard with a built-in amplifier. Its one-note-at-a-time sound became popular in pubs in post-World War II England. (Check out the Tornadoes' 1962 recording of “Telstar" to get an idea of what it sounded like.)

Modern-Day Alternatives

- Vox AC30HW2X Handwired,

$1,999 street, voxamps.com -

Matchless DC-30,

$3,800 street, matchlessamplifiers.com -

Dr. Z Stang Ray 1x12 combo,

$2,299 street, drzamps.com - Top Hat King Royale 2x12,

$2,999 street, tophatamps.com -

65 Amps London Pro 1x12,

$1,995 street, 65amps.com

But it was the up-and-coming popularity of rock 'n' roll in the latter half of the '50s that prompted Jennings to reunite with his wartime buddy Dick Denney to produce an amplifier designed specifically for guitarists.

Fender amps were available in England, but at a hefty cost. Not only did shipping make them prohibitively expensive, they also required a step-up transformer to run on the U.K.'s 220V grid. The AC30's pint-sized progenitor, the AC15, was born in 1958. Manufactured in Sussex, the “Amplifier Combination 15 Watt" was the affordable answer to Fullerton imports.

The AC30 on Record

The Beatles Please Please Me

Rory Gallagher Deuce

Queen A Night at the Opera

U2 The Unforgettable Fire

Radiohead OK Computer

It quickly became the 6-string voice of Hank Marvin, guitarist in the popular instrumental group the Shadows, as well as with popular Merseybeat group the Big Three, Lonnie Donegan, and other guitarists—and, yes, accordionists—in the U.K. Its instantly recognizable sound—glassy, chimey, and sweetly compressed when driven—defined early British rock. The AC15's tube complement—a pair of Mullard EL84 power tubes (or “valves" in British parlance) and a high-gain EF86 pentode in the preamp—were a key difference between the Vox and Fender sound.

But the increasing popularity of rock 'n' roll soon led to bands being booked in larger venues (never mind the fact that rock drummers were also getting louder). To keep up, guitarists were looking for more volume. Enter the AC30, which doubled the AC15's power section with four EL84s producing 30 watts of class AB power.

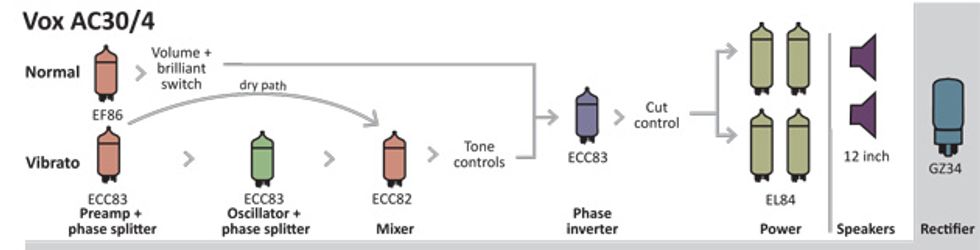

According to Jim Elyea, author of Vox Amplifiers: The JMI Years, Dick Denney's original single-speaker AC30 built in 1959 featured two EL34 power tubes. In order to work in conjunction with two speakers, however, the EL34s would have required a taller cabinet than what we're accustomed to today. So four EL84s enabled use of a smaller, more manageable chassis. According to David Petersen and Dick Denney's book, The Vox Story, the Shadows took possession of the first three AC30s in late 1959. Interestingly, for a short time three versions of the AC30 were simultaneously on the market: the one-speaker EL34-powered AC30, the AC30/4—which had four input jacks, an EF86 preamp tube, four EL84s, and two speakers—and the AC30/6, which had six inputs, a 12AX7 in place of the EF86, four EL84s, and two speakers.

What about the AC34?

Vox fanatics who deep-dive into the company's history are sometimes vexed by the mention of a mysterious “AC34" design—including on an April 1960 Jennings Musical Instruments schematic. Author Jim Elyea demystifies the moniker for us: “If you say 'AC30/4' to someone, it sounds identical to 'AC34.'" In other words, there's not some ultra-rare model out there. The “AC30/4" and “AC34" are the same amp. The confusion—apparently even at JMI in 1960—arises from the failure to verbalize the slash mark in the model designation.

Fender “Blackface" Twin Reverb

Seven years after their very first amplifiers began rolling off the line, Fender introduced the original “wide panel" tweed Twin. Its 25 watts excelled at clean, loud tones that were great for country artists and others who were playing in larger venues. The Twin joined the ranks of the Bandmaster, Champ, Princeton, Deluxe, Super, Pro, and Bassman in 1953, but it took another 10 years for the much louder, 85-watt Twin Reverb—with its sleek, “blackface" cosmetics—to emerge.

The Twin Reverb wasn't Fender's first reverb-equipped amp—that prize goes to the Vibroverb, which came out in February 1963. The Twin Reverb followed in September, and the Deluxe Reverb and Super Reverb also came out that year.

Modern-Day Alternatives

-

Fender '65 Twin Reverb Reissue,

$1,449 street, fender.com -

Music Man 212 HD 130,

$TBD, music-man.com -

Roland JC-120 Jazz Chorus,

$1,199 street, rolandus.com -

Tone King Galaxy head,

$2,595 street, toneking.com - Victoria Golden Melody,

$2,970 street, victoriaamp.com

Fender's reverb boom wasn't over, though: The Princeton Reverb debuted in '64, and the Pro Reverb came out in '65. For a long lineage of guitarists, however, the Twin started a love affair that's still going strong more than 50 years later.

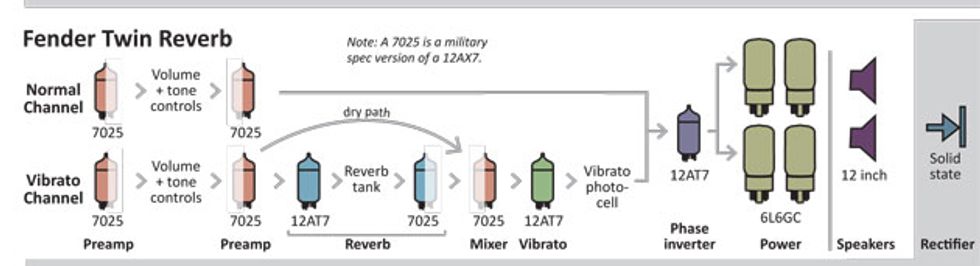

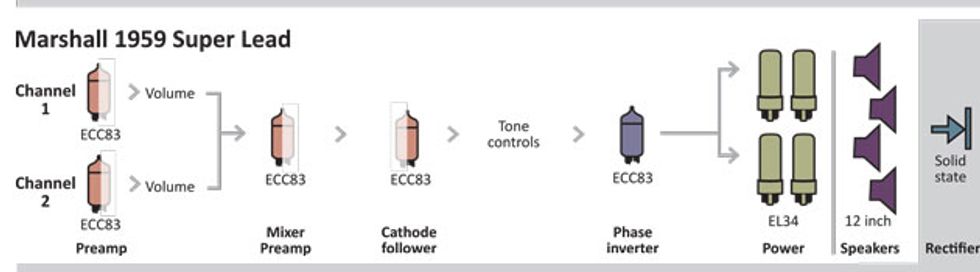

Originally, the 2-channel, 10-tube amp's “normal" and “vibrato" channels each sent the guitar signal through both halves of a 7025 tube—a low-microphonics military version of a 12AX7. The vibrato channel uses another half of a 7025 tube for a second gain stage. A 12AT7 phase inverter sends the preamp signal to four 6L6GC tubes driving a pair of 12" speakers—usually ceramic-magnet models like a Jensen C12 or an Oxford 12T6, though alnico-magnet JBL D120Fs were available for an upcharge.

The Twin Reverb on Record

The Beatles Abbey Road

Mike Bloomfield Super Session

Buck Owens and His Buckaroos Carnegie Hall Concert

Eric Johnson Ah Via Musicom

Nirvana In Utero

The reverb section uses both halves of a 12AT7 for the driver, and half of a 7025 for the return (sharing that tube with the vibrato channel's second gain stage). The vibrato circuit uses both halves of a 12AX7. The rectifier is a solid-state unit.

Fender produced Twin Reverbs through 1986, though they changed considerably along the way, most notably with the 1968 switch to “silverface" cosmetics. According to Jeff Bober, Premier Guitar's Ask Amp Man columnist and owner of EAST Amplification, the first year's worth of silverface Twins' bias, phase-inverter, and output-stage circuits differed from their predecessors, resulting in a semi-cathode-biased design that reduced overall volume and had a tendency to compress much more easily. The next year saw a return to the louder fixed-bias design, though the other changes remained—and more would follow (including the curious 1972 introduction of a master volume).

In 1982, Fender attempted to modernize and diversify the Twin Reverb sound with the Paul Rivera-designed Twin Reverb II, which shunned the tremolo circuit and adopted a distortion control. In 1992, the Twin Reverb's venerated history led to the '65 Twin Reverb Reissue line, which is based on early blackface models and continues to be a favorite for a wide variety of players to this day.

The classic Twin sound is the powerful, bell-like tone of early blackface models. Twins have been used by the Beatles, Mike Bloomfield, Jerry Garcia (his first amp was a '63 Twin Reverb that he used for most of his career), Keith Richards, Don Rich, Steve Howe, B.B. King, James Burton, Steve Jones of the Sex Pistols, Eric Johnson, and even Kurt Cobain. In short, Twins have been and are everywhere. They're clean at virtually any volume, making them a nice jazz amp or an impeccable blank canvas for pedal experimentation—which is why pedal manufacturers and reviewers often use them to audition pedals.

Marshall 1959 Super Lead

London's Seventy Six Uxbridge Road must have been an interesting place in 1962: Jim Marshall, a proficient drummer, had just opened a drum shop where he taught future Hendrix drummer Mitch Mitchell, among others. Customers would often bring along their guitar- and bass-playing bandmates, and eventually the shop became a hangout for rockers like Ritchie Blackmore and Pete Townshend.

Conversation often turned to gear, and Marshall—who'd already been making speaker cabinets for bass players—soon learned that the 1957 Fender Bassman that so many players coveted had been discontinued in favor of the 6G6 blonde version. And when he heard that even the coveted '57 Fenders weren't giving rockers what they needed, he decided he'd solve the problem with his own design.

It's worth noting that, though there probably wouldn't have been any Marshall amps were it not for the untimely demise of the 5F6A Bassman, it's equally likely the Bassman wouldn't have existed without the 1951 RCA Receiving Tube Manual's detailed description of a “High Power Audio Amp." Each led directly to the other.

Modern-Day Alternatives

-

Marshall 1959SLP Super Lead,

$2,499 street, marshallamps.com -

Bogner Helios,

$2,799 street, bogneramplification.com -

Friedman Brown Eye,

$3,699 street, friedmanamplification.com - Suhr SL-68,

$2,299 street, suhr.com -

3rd Power HD100,

$2,499 street, 3rdpower.com

In 1962, the Marshall team built their first amp, the JTM45, with the goal of providing guitarists with a more aggressive sound. It wasn't an exact Bassman clone, just as Leo Fender's Bassman wasn't an exact clone of the RCA amp—but in both cases the deviations from the circuit that inspired them were minor. While Marshall followed the Bassman circuit almost identically, they were limited to components available in England.

They first used 5881 (aka 6L6) power tubes, just like the Bassman, but soon changed to KT66s. The JTM45 also used a 12AX7 as the first preamp tube (as opposed to the Bassman's 12AY7), which resulted in very different gain and loading characteristics. Marshall's first amp also used an extra brightness capacitor, as well as a feedback circuit taken from the 16-ohm output (rather than the Bassman's 2-ohm output).

The combination of the JTM45 with Marshall's 4x12 speaker cabinets hooked the Who's John Entwistle and Pete Townshend—the latter of whom also contributed design ideas to the Marshall team, which included Dudley Craven and Ken Bran. Alas, by 1965 JTM45 stacks weren't cutting it for arena acts. The Who switched to 100-watt Vox amps for a time, but purportedly found them unreliable. Townshend then challenged Marshall to double the power of the JTM45.

The Super Lead on Record

Cream Disraeli Gears

Jimi Hendrix Are You Experienced

AC/DC High Voltage

The Ramones Rocket to Russia

Van Halen Van Halen

Not every version of Marshall's 100-watt amps was called the 1959 Super Lead. The 1959 name showed up in late 1967, stemming from its item number in a catalog. Regardless, continuing development on the 100-watt head that would eventually be known as the 1959, the company tried four 6V6 power tubes, followed by four 6L6s, then four KT66s.

Four big tubes require a lot of current, and the existing power transformers weren't up to it. This resulted in a sag-induced compression as the power transformer struggled to keep up. As the team experimented with filter-capacitor values in the power section, they noticed tonal variations. There were also various output-transformer approaches as the quest to refine the circuit continued. Early in 1967, Marshall abandoned KT66s for EL34 power tubes and yet another output transformer. In all, there were no fewer than 15 iterations of the Super Lead between 1965 and 1969—including the mid-'69 switch from Plexiglas to metal control panels.

This rather cursory explanation of the Super Lead's evolution helps explain vintage-amp junkies' perennial quest for “a really good plexi." Compounding the mysteries of the model's various iterations is the fact that, in those days, electrical component values could vary widely due to less exacting manufacturing methods than are available today. So while any two amps off the line might contain parts labeled with the same values, the cumulative effect of loose component tolerances meant each amp could sound markedly different.

But that didn't stop the 1959 from going down in history as the 100-watt of choice for everyone from Jimi Hendrix to Eric Clapton, Edward Van Halen, Warren Haynes, Eric Johnson, Yngwie Malmsteen, and many, many others.

Hiwatt DR103

“Made redundant" is a British term for losing your job. And in 1966, that's what happened to Dave Reeves while working at the revered Mullard tube factory in Surrey, England. He rebounded quickly though, founding the Hylight company and diving into designing and building high-powered amps for Sound City, the famous London music shop where Buddy Rich, the Beatles, Jeff Beck, Hendrix, and others often bought gear.

Hiwatt expert Mark Huss, whose website hiwatt.org provides a detailed history of the company, says the now-legendary amp name first showed up on an amp built by Reeves as far back as 1964—although it was possibly a one-off project. In 1968, following his Sound City amp-building stint, Reeves started building a line of high-powered amps under the aptly named Hiwatt brand.

Modern-Day Alternatives

- Hiwatt Custom 100 DR103,

$2,999 street, hiwatt.com -

Reeves Custom 100,

$2,399 street, reevesamps.com -

Jaguar HC50 combo,

$2,029 street, jaguaramplification.com -

Hi-Tone HT100 DR,

$1,939 street, hi-tone-amps.com -

Ceriatone Hey What?! 103,

$1,140 street, ceriatone.com

Although some might say Hiwatt followed on the coattails of Marshall, Reeves designed quite a different amp. He also benefited from the fallout of a money-related disagreement between the Who's manager and Terry Marshall (Jim's son), after which Pete Townshend turned to other amp providers. He first tried Sound City amps, then—naturally—Hiwatt.

Townshend's legendarily loud quartet was always looking for more volume, and he found happiness in Reeves' 100-watt Custom 100 DR103. Armed with four Mullard EL34 power tubes, it easily exceeded 100 watts. In contrast with Marshall's high-powered offerings, the DR103 had less breakup when turned up loud. Actually, it had no real breakup until cranked to ear-shattering levels.

The DR103 on Record

The Who Live at Leeds

Jethro Tull Aqualung

Pink Floyd The Wall

Led Zeppelin

Led Zeppelin DVD

The Strokes

Is This It

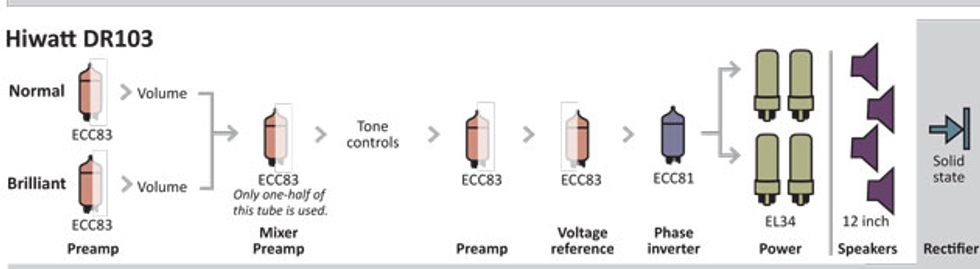

The DR103 circuit was identical to Hiwatt's 50-watt Custom 50 DR504 amp, but it doubled the number of EL34s for twice the power. According to Kee Mayer, engineer and builder at the current Hiwatt manufacturing facility in Doncaster, England, Reeves designated the original DR103 circuit with the letters “AP" because pulling two EL34s resulted in a 50-watt amp that's more “all purpose." Fully stocked, the solid-state-rectified DR103 has eight tubes—three ECC83s (12AX7s), one ECC81 (12AT7) phase inverter, and four EL34s. (That said, one of the DR103's ECC83s is only half used.)

In 1970, Hiwatts formed the backdrop for Townshend's Live at Leeds acrobatics, paving the way for them to become go-to amps for power- and volume-hungry players. By 1971, demand had increased so much that Reeves needed help.

In the phone book he found a listing for Harry Joyce Electronics, whose proprietor had military contracts requiring high standards of quality and durability. To maintain those standards, Joyce limited his chassis-wiring workload to 40 per month.

Between the 14-ply, tongue-and-groove Baltic birch cabinets and Joyce's military-spec chassis, Hiwatt durability went above and beyond typical standards. Partridge Transformers provided custom models, and Fane produced speakers with cast-metal frames. Over-the-top quality, durability, and attention to detail became synonymous with the brand—not to mention tones rich in edgy, third- and fifth-order harmonics. Playing through a cranked vintage Hiwatt stack is not for the faint of heart: Burly sounds lunge from the cabs almost instantaneously, revealing every detail and nuance of pick attack and fretwork. The classic Hiwatt tone is an exquisite blend of muscle and musicality.

While there's no longer a connection between Hiwatt and the Reeves family—nor between the family and the Hiwatt-inspired designs from U.S.-based Reeves Amplification—current owners of the brand still have a lot of respect for the standards that Reeves and Joyce set. Current-production DR103s still feature handwired, turret-board construction.

Mesa/Boogie Dual Rectifier

The first of Randall Smith's famous line of hot-rodded amps started appearing with the Mesa/Boogie moniker around 1970. However, early amps known as “Princeton Boogies"— Fenders that Smith heavily modified—date as far back as 1967. Working in what he called “the Dog House" in Lagunitas, California, Smith started experimenting to see if he could cram a Bassman-like amp into a Princeton-size cabinet.

It worked. The 100-watt, 6L6-powered amps soon garnered attention from such high-profile players as Carlos Santana and Keith Richards, almost immediately establishing Mesa/Boogie as a serious contender in the amp market.

Modern-Day Alternatives

-

Mesa/Boogie Dual Rectifier,

$1,949 street, mesaboogie.com -

Diezel Lil' Fokker,$2,499 street, diezelamplification.com

-

Blackstar HT Metal 100,

$1,049 street, blackstaramps.com - Peavey 6505+,

$1,299 street, peavey.com -

Fryette Pittbull Hundred/CLX,

$2,799 street, fryette.com

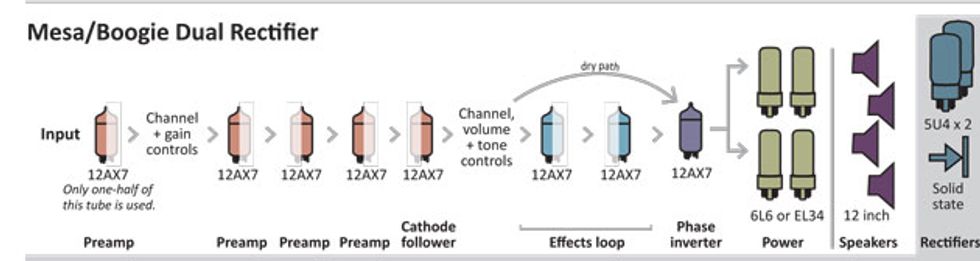

But while Smith's team released many notable designs thereafter, Mesa's most influential amp—the Dual Rectifier—came roughly 20 years later, in 1991. Whereas previous Boogies had much in common with Fender circuits, the Dual Rec's lineage has more British-like origins. R&D guru Doug West made an urgent phone call to Smith from his hotel room one evening late in the '80s. He'd noticed many guitarists at the time were leaning towards specially modified Marshalls, and he felt it was time for Boogie to respond.

After lots and lots of listening, the company began work on a design with cascading gain sections for more brutal tones. They used a smaller chassis for the prototype, crowding it with tubes, rectifiers, and other components in search of the right sound. Once they'd perfected it, they found transferring the same sound to a printed-circuit-board version was just as challenging. But by late 1990 they'd figured it out.

The Dual Rec on Record

Metallica Metallica

Dream Theater Awake

Soundgarden Superunkown

Helmet Meantime

King's X Dogman

As its name suggests, one of the keys to the new high-gain Boogie's sound was its use of two rectifiers. Wall voltage is AC (alternating current), meaning it exits the wall socket as a sine wave. But amps need DC (direct current)—a continuous voltage. All tube amps have rectifiers, either a tube (sometimes two) or solid-state diodes. The latter tend to result in higher voltages and, therefore, more clean headroom at higher volumes.

The lower voltages of tube rectifiers tend to result in earlier breakup and a nice, bluesy distortion. At high volume, tube-rectified circuits also tend to exhibit more “sag"—a pleasing, naturally compressed sound often associated with vintage amps. One of the most intriguing aspects of the new Dual Rectifier was that you didn't have to choose either one or the other—you could switch between tube or solid-state rectos with the flip of a switch on the back of the amp.

Another Dual Rec innovation was its bias switch, which let users choose which high-gain octal tubes—6L6 or EL34—they preferred. It also featured two footswitchable channels—a handy feature many of us take for granted today, but that was pretty mind-blowing at the time. The amp's 11 tubes include two 5U4 rectifiers, five 12AX7s, and four 6L6s or EL34s. Why two 5U4s? Just one can't handle all the current.

When all's said and done, the Dual Rec—and its many Boogie spinoffs (not to mention hordes of copycat amps)—is most prized for its ability to instantaneously switch from crushing distortion and infinitely sustaining leads to brawny, super-clean sounds. Early adopters included a who's-who of metal players, including Metallica's James Hetfield and Kirk Hammett, Dream Theater's John Petrucci, as well as Tim Mahoney of 311, Dave Grohl, and many, many others.