Nels Cline has led something of a double life for the past 16 years. While known widely as the virtuosic, guitar-wielding, not-so-secret weapon of beloved alt-country originators Wilco, Cline has simultaneously tended to an extremely prolific career as a genre-busting composer, 6-string innovator, and solo artist, and built a reputation as one of the most vital improvisers of his generation.

His astounding number of extracurricular musical pursuits include a critically acclaimed album of duets with jazz guitar wunderkind Julian Lage (2014's Room) and an ambitious double-disc concept album called Lovers, which not only found Cline a home at the revitalized Blue Note Records, but might be the only album ever to feature covers of songs by both Henry Mancini and Sonic Youth. And let's not forget his imaginative CUP duo project with his wife, Yuka C. Honda of Cibo Matto.

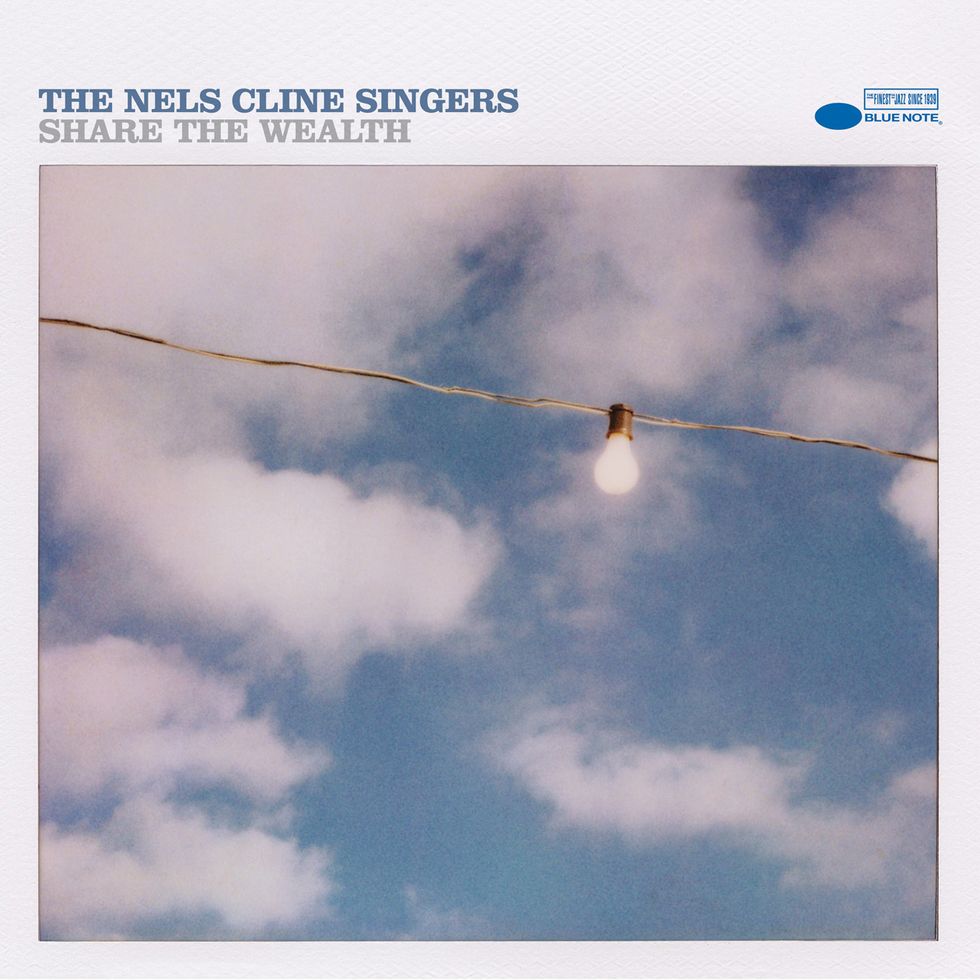

While there have been countless liaisons and contributions to the albums of others throughout it all, Cline's true musical home—even before he joined Wilco—has always been his own cleverly named instrumental outfit, the Nels Cline Singers. With the Singers' latest, Share the Wealth, Cline's chameleonic, cinematic guitarwork and compositional chops have been thrown into exciting new territory again, thanks to an expanded lineup of improvisational sparring partners whose skills may have inadvertently spoiled the guitarist's grand vision for another concept record, but to absolutely wonderful effect.

When Cline first hatched the idea for what would become Share the Wealth, the plan was for the freshly expanded Singers lineup—now a sextet—to record a batch of minimally guided improv sessions, which he would then chop up and reimagine via the wonders of DAW editing into a sort of sonic collage—something with a '60s Brazilian-psychedelia flavor in the vein of Os Mutantes.

Cline also planned to have the squad take a stab at some of his more concrete compositions. Brazilian percussion ace and composer Cyro Baptista (Trey Anastasio, Herbie Hancock), avant-garde tenor sax antagonist Skerik, and keyboard wizard Brian Marsella joined Cline and longtime Singers bassist Trevor Dunn (Mr. Bungle, John Zorn) and drummer Scott Amendola for two days' work at Brooklyn's the Bunker Studio.

Despite the impressive resumes of the Singers' new additions, Cline was unsure if the sessions would yield anything album-worthy, as this lineup had no gigs under its belt, making its chemistry as a unit a major unknown. However, when Cline listened to what the band had captured during those improv sessions, he found something magical. In fact, the guitarist was so impressed with how well the raw material worked in its unedited form that his plans for a chopped-and-screwed sonic collage went out the window altogether. Tchau!

On Share the Wealth, those improv jams now appear—and blend remarkably well—with the Singers' take on some of Cline's originals. And despite the lack of major editing, the album'sfinal formis still a psychedelic-tinged aural adventure in which Cline and company take the listener on a journey through impressively executed and dynamic musical arrival points.

Share the Wealth is not only a fine display of the uncanny playing chemistry and clairvoyance that exists between Cline and his Singers—it's also one of his most approachable releases. The album boasts Brazilian-tinged guitar vamps (“Segunda"), playful backbeat groovers (“The Pleather Patrol"), a pair of somber but beautiful ballads written for a fallen friend (“Passed Down" and “Headdress"), and a stunning, meditative Kubrick-gone-free-jazz odyssey (“A Place on the Moon").

Cline's guitar often plays a supporting role on this album, creating unique textures, dancing around and coalescing with Skerik's wild saxophone outings and Marsella's perpetually morphing keys. While this might leave fans of his formidable linear chops a little flat, the results are extremely musical and mature. Of course, there are still shining moments of guitar mastery that see Cline reaching for exotic harmony on the Tuareg-influenced album closer “Passed Down" and a few blasts of the man's signature off-kilter free-jazz weirdness, but it's applied in a decidedly less confrontational way.

Premier Guitar spoke with Cline by phone as he enjoyed the solitude of his new home in upstate New York, where he reflected on the process of recording the Singers' new release and discussed the relatively simple (for a man with a famously ever-expanding guitar collection) selection of gear he brought in for Share the Wealth'ssessions, the mastery of improvisation, staying sharp as a musician at a time when most of us can't play with others, and his endless love for the abstract nature of sound.

I love your original concept for editing improv sessions into a William S. Burroughs-esque cut-up Brazilian psych album. What made you abandon that?

I honestly didn't even know if we had a record after we finished the sessions. The thing is, we've never even played a gig with this expanded version of the Singers. Listening back to what we did when we were just improvising and messing around, I really loved the chemistry there and what we'd done. I really liked hearing us arrive at these musical places and make these shifts very naturally as a band. A lot of the transitions and shifts on the album sound like edits, but they're just what came out. I didn't set out any specific parameters for the improv during these sessions, other than for the session that became “A Place on the Moon," and I just said to everyone “space" on that one. On all the other songs, the other guys were just given BPMs that I chose randomly as click tracks in headphones, thinking that I would have everything on the grid so I could do these bold, jarring juxtapositions that I was envisioning.

TIDBIT: Ambitious and free-ranging, Cline's new album took just two days to record at Brooklyn's the Bunker Studio, with engineer Eli Crews.

What's the ratio between improvised work and composed stuff on the album?

The record's maybe a third improvised, as far as what I chose to include. Nobody had played any of the written material prior, and we did it all in two days. I had to time compress songs because some improvs were over 30 minutes, but I didn't edit the trajectories of how any of the improv sessions went at all. There are three complete improvs on the record: “The Pleather Patrol," “A Place on the Moon," and “Stump the Panel."

The original improv that became “Stump the Panel" was well over 20 minutes, and Scott Amendola forgot to put the click in his headphones, but it worked really well. I would just randomly say a BPM to our engineer and co-producer, Eli Crews, and he would put the click in our headphones for the areas of free improv.

For “Stump the Panel," Scott started out playing all this wild stuff and we were all looking at each other like, “what is going on here?!" So we just turned the click off and did our thing, because he'd just taken off and all this cool stuff started to happen in that jam. When I listened back to this really long improvised jam, I was like “Wow, I really like this! I like this more than the tunes that I've written!" It was a delightful surprise.

This group moves as a unit in a way that genuinely sounds like you've played together a lot. You do a lot of support playing this time around, too.

I felt the same thing, and I do have a long track record of playing with Scott [Amendola] and Trevor [Dunn], and even Cyro [Baptista] and I have toured together a bit, but how well Brian Marsella and Skerik worked in the mix was really a pleasant surprise. Brian and I had played together and he'd done an expanded lineup gig with the Singers at the Victoriaville Festival a few years ago, and that was where the seeds for this lineup were planted. I had a desire to have musical foils in the treble clef area, to take some attention away from my playing and help me relax a little bit. I was becoming quite daunted and fatigued with being the lead guy in power trios all the time. I really like to play off of somebody.

I didn't really know what the role of the guitar was going to be in this version of this band. Once I got in the studio, I realized I didn't really feel like standing out. My head was in a more supportive role and I was focused on doing a lot of looping and sound making and harmony on-the-fly, rather than the single line blazing or finger wiggling that people expect from guitarists who lead bands. I'm not super comfortable listening to myself do that kind of thing at this point. There's a little bit of that playing on the album. “Headdress" was something where the guitar and the keyboards are really hard to distinguish from one another, because they're meshed into the same sonic realm deliberately. I did overdub the melody that Skerik's playing at the end to add some emphasis. That was my big production touch!

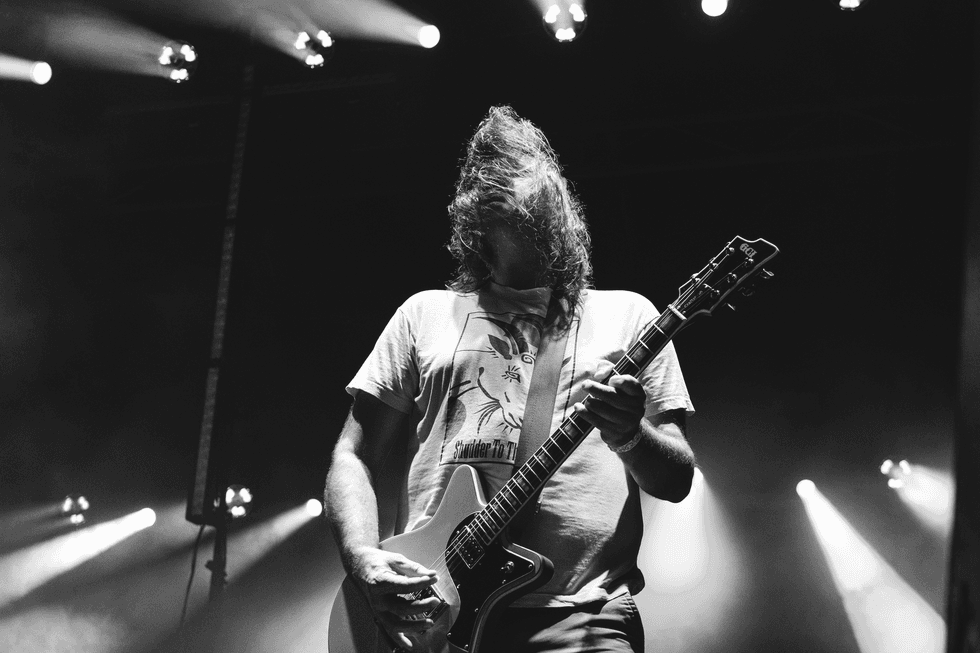

Onstage with Wilco, Cline manipulates his Korg Kaoss Pad 2 as he plays textural lap steel. He also uses 12-strings, Gibsons, and a host of other guitars with Jeff Tweedy and company. Photo by Jordi Vidal

Did you do much in the way of overdubs? It sounds like such a complete and layered album.

I added a few things here and there. “Ashcan Treasure" was something I sketched out in the studio, because I wanted to do a piece playing dobro with Brian on toy piano. I added the middle section later, with overdubs using the Gamechanger Audio Plus pedal and flying in little musical moments between Scott and Cyro from some of the raw improv recordings. So there is some editing involved, but mostly just to keep things shorter and to make long pieces into something that hopefully someone would want to listen to more than once.

The tune that was the most important to me became “Beam/Spiral," and I had been working on the main chordal riff of that piece for months without ever really finishing the actual form of the song. It finally showed up right before the session. That's the most produced piece, in that I did guitar doubling and subtle sonic touches in the second half of the tune when the song starts really rocking. I do little overdubs and doubling parts on a lot of Singers records just to add texture and highlight sonic qualities I liked in the first guitar parts.

“Passed Down" and “Nightstand" were ballads that I wrote to deal with some heavy grief over a friend's suicide, so I just wanted to record them and see if they fit in any kind of capacity on the record. I'm glad they did.

I hear a bit of West African guitar phrasing on “Passed Down." Was that flavor intentional?

That was very intentional, and I hope people don't find it touristy, but I was just playing what I wanted to hear. There's definitely the influence of the Tuareg world and of Ali Farka Touré in there, but always lurking in my consciousness, since I was maybe 10 years old, is some touristic version of Indian classical music, which is also evident in the intro to “Headdress." I'm no scholar in these areas and I don't wish to offend anyone in these touchy times by overdoing that influence, but that music is a part of my sphere of reference and its sound is something I like hearing when I play.

What gear played an important role for you on this one? I assume it was a wild selection pulled from your infamous collection of guitars and effects.

There wasn't that much brought in, because it was mostly tracked in Brooklyn at the Bunker and you can't easily carry a million guitars there. I knew specifically what I needed for these songs going in, so I only brought four guitars with me. I used mostly my '59 Fender Jazzmaster and a parts Jazzmaster that I use a lot in New York because it has Seymour Duncan PAFs in it that look like Jazzmaster pickups, but it's often necessary to have a guitar that doesn't hum in New York, with the old wiring in buildings. That guitar sounds a little more like an SG or something.

John “Woody" Woodland of Mastery Bridge fame put that parts Jazzmaster together for me using a vintage body, a kit neck of some sort, a vintage tremolo, and a Mastery bridge, and that guitar has become my main recording guitar when I'm in New York. People also really like the sound of it and I still get my Jazzmaster feel with the strings behind the bridge and all that, but with a slightly different sonic signature. I used that one on “A Place on the Moon," because I was doing volume swells with the compressor on and didn't want to bring up a bunch of 60-cycle hum with each swell.

I also used a vintage Danelectro Convertible a lot. “Passed Down" is that guitar mic'd acoustically and with its electric signal mixed in. I also used that guitar to overdub the strumming on “Beam/Spiral." I also used my dobro a lot! It's just this insane guitar that once belonged to some man named Curtis Rogers, and no one knows who he was, but the guitar is extremely distressed-looking and one of the vibiest I've encountered in my entire life. I purchased that dobro from TR Crandall in NYC, and Tom Crandall had completely rebuilt this guitar. It has a painting of a woman on it that was supposedly Curtis Rogers' wife, and it has this amazingly deep timbre for a dobro. I'm sure it's from the early '30s, and for some reason the biscuit in it didn't go flabby. This Curtis Rogers guy obviously played it to death, because the entire fingerboard had to be replaced.

I used the full main pedalboard that I use all the time with the Singers or when my wife and I do our CUP duo. The amp used is a Studious Moseley 1x12 combo, which is the combo version of the amp I use with Wilco. I think this one has a Weber in it, but I'm not positive. I prefer it because it's so simple. It doesn't have too much treble and has really nice low-mids.

Did you do anything weird with effects routing or experimentation?

Not at all. I had to be able to just flop this stuff down on the floor and be ready to go, because there was no time for futzing around. When I first joined Wilco and started acquiring all of these guitars, I didn't have to put kids through college and I had cheap rent for a while. I've been horrendously enabled by Mr. Tweedy's knowledge and love for guitar accumulation. I really had this idea that I was going to have all these guitars that I could bring into a recording situation and pick all of these arcane guitars and pedals and amps and create unique tones and original, signature sounds—and there's just no time for that! And how are you going to get them to the studio when you live in the city? I always go back to my '59 Jazzmaster, and I don't know why I stray, but I think it just comes from restlessness.

The Danelectro Convertible has become my favorite guitar to just sit around playing, and that's why it ended up on the record. I really love its acoustic sound, because it's got this weird hybrid tonality that's a little banjo-like and a little bit hard to describe. I just love those lipstick case pickups, and I've always found the quality and feel of Danelectro and Silvertone guitars appealing. My Convertible is from the '50s, and it came from New Jersey, near where the original Danos were made, and it was well-played. It needed a total neck reset, and Tom Crandall once again really dialed it in. There's just something about this particular guitar and its acoustic properties that speak to me.

“Segunda" is a vamp on the Gal Costa song of the same name, written by Caetano Veloso. The lyrics of the original address racial and social inequality, and I'm curious if you could expound upon the idea of using instrumental music to express things like that through quoting melodies. I think that subtext can really elevate instrumental music and force the listener to look deeper at something that could just as easily be enjoyed on a surface level.

I certainly have ideas to take songs that are intriguing lyrically, melodically, harmonically, or all three, and try to do something of my own with them. That's what I did on the Lovers album, with songs like it “It Only Has to Happen Once" by Ambitious Lovers or “Snare, Girl" by Sonic Youth, and that's really what jazz does. When you look at the Great American Songbook, most of those jazz standards were originally vocal songs that had lyrics about love or being lovelorn. I think the same impulse that inspired jazz musicians way back when to take the popular music of the day and turn it into something else as an instrumental foray is the same impulse that inspires me to take a song that is intriguing in any way and interpret it as an instrumental.

Guitars

1959 Fender Jazzmaster

Parts Jazzmaster built by John Woodland, with a vintage body, modern neck, Seymour Duncan JM-sized PAFs, vintage tremolo, and a Mastery Bridge

1950s Danelectro Convertible

1930s National resonator

Amps

Studious Moseley 1x12 combo

Effects

Main Board:

Boss TU-2

DigiTech Whammy

Seymour Duncan 805 Overdrive

Boss CS-3 Compression Sustainer

Boss DD-3 Digital Delay

Electro-Harmonix Stereo Pulsar Variable Shape Tremolo

Boss VB-2 Vibrato

Devi Ever Soda Meiser

ZVEX Fuzz Factory

Jam Pedals WaterFall chorus

Crazy Tube Circuits Vyagra Boost

Boss FV-500 Volume Pedal

Gamechanger Audio Plus

Neunaber Immerse Reverberator

Montreal Assembly Count To Five

Korg Kaoss Pad 2

Electro-Harmonix 16 Second Digital Delay

Strings and Picks

GHS Boomers (.012–.052)

GHS Boomers (.012–.056, with wound G for the Danelectro)

Dunlop Ultex 1.14 mm

Dunlop Adamas “Jerry Garcia" 15R 2 mm

It was actually kind of an accident that this one was so perfect for the current moment. My wife turned me on to the Gal Costa record Recanto, and there is something about the song “Segunda" that just stuck with me. I wanted to try to do my version just so I could hear it, and it's something about the way the melody works against that drone. I'm a drone fiend, and I think I understand modal music really well and love the limitations of modal music. But it wasn't meant to be topical in any way. My choice to cover it was purely musical and I didn't know anything about the original song's lyrical content until I asked Cyro and his wife what the song was about, and they translated it for me. The lyrics are extremely poetic and Cryo was freaking out about how “this song is for right now!" So my impulse to do it was purely musical, and it just happened to be this uncanny coincidence.

That said, I'm still most interested in how instrumental music lacks any kind of didactic or concrete message, and I think the beauty of it is in its abstraction and how sound feels.That's what's most important to me. Sometimes an electrifying display of technique is electrifying to the listener, but, more often than not, I'm drawn to resonance, timbres, and rhythms, and that's a pretty abstract realm where I'm most comfortable.

When I was a kid, I just didn't care about lyrics. I was totally sound-focused. I wanted to hear fuzz guitar or cool blues guitar playing, and I listened to blues guys and I didn't really care what they were singing about. I kind of cared about Neil Young's lyrics, because I was a depressed teenager, but overall I never paid attention to lyrics the same way I did to sounds. Certainly, after 16 years in Wilco, I'm much more sensitive to the power of lyrics, but I'm still pretty much a sound baby.

You've stressed over the years that you're an extremely active listener when you improvise. A lot of players are shacked up at home and haven't had the opportunity to play with others for quite a while. I'm curious if you have any advice for those trying to develop the skill of listening in a present way, while playing and mastering the trick of simultaneous input/output?

They're calling it 6-string therapy! I can say that ear training is extremely helpful, and knowing intervals is really nice. One can develop pretty good relative pitch skills just from listening and having your instrument in-hand and trying to recognize notes consistently. You can pretty much tell which notes the guitar is playing in music, because you can use things like picking out open string sounds compared to fretted notes, and there are so many chords you've heard over and over again that you eventually learn to just recognize them. I never thought it was a bad thing to play along with records, and while it's a one-way street, it does really develop your ear. When it comes to improvising, I don't have a specific system, but I think it's just good practice trying to keep the idea in your mind that you need to be listening the entire time you're playing—like mindfulness training.

A good practice—and actually a very fun one—is putting on a super open, free, improvised record like something from the '70s by Leo Smith's band New Dalta Ahkri, which is great because his note choices are really abstract, or maybe the Art Ensemble of Chicago, or something more tonal like Keith Jarrett's solo piano stuff, and just play along with it and see if you can fit in somehow and pretend you're a part of the band. I think playing along with records when you're alone is a really important thing to do, and especially now.

You've worked with Trevor Dunn for years, and he has an extremely diverse resume. What does Trevor's playing bring out in your own? And the same for Skerik.

What Trevor provides for me is complete freedom to be myself. Because Trevor has this wide-ranging sensibility, I can pretty much ask him to do anything musically and he gets it right away. I don't have to explain anything to him and that makes me feel completely free. I never have to worry about a song being too limiting or overwhelming for him. Playing with Trevor just keeps me relaxed and not concerned about what he's going to play or not play, and free to do my thing and stay present.

In the case of Skerik, I never thought of having saxophone in the Singers until I played this post-Phish show jam with him at Sony Hall [in Times Square]. I was so impressed by his facility with effects—which is not gimmicky at all—and his ability to play melodically direct with this amazing tone. Skerik is really versatile and can reference an entire school of pre-jazz sax, which is to say he can really wail and shriek if need be, but he can also do highly considered lines and R&B, and he has an amazing tone. He fits right in there with what I do, and I can't wait to play live gigs because he and I will be able to play off each other, and the same goes for Brian Marsella. When I was thinking about this tenor sax and guitar thing, which is admittedly well-trod, I hadn't really thought about the incredible similarities in timbre and range between an overdriven guitar and a tenor sax … and it's so obvious! We're pretty much right up in each other's frequencies, so the potential for interesting counterpoint and symbiosis looms large with those two instruments and worked out really well on the album.

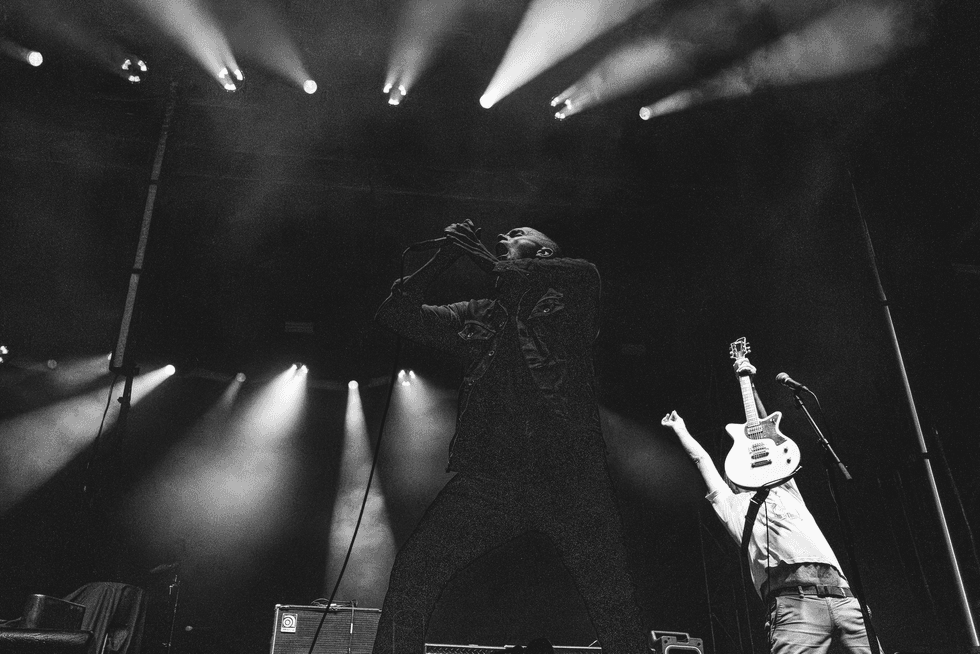

And now for something completely different: Nels Cline performs a tribute to Jimi Hendrix at the Brooklyn Music School in February 2018, with guest guitarists Sean Lennon and Captain Kirk Douglas of the Roots. And yes, this show's about wailing guitar.