About two years ago, after finishing his third consecutive Grammy-winner (2020’s Have You Lost Your Mind Yet?), Xavier Dphrepaulezz—aka Fantastic Negrito—did some research on Ancestry.com. As with many of the site’s patrons, the results blew his mind.

“I was like, ‘Holy shit!” he says. “I didn’t know I was a seventh-generation descendent of a white Scottish indentured servant and a Black enslaved person. 1700s? How did they do that? How did they live? No one killed them?’”

On his mother’s side, his ancestor was a woman from Scotland sold to work in 1750s colonial Virginia. She lived, somehow, in a common-law marriage with her enslaved Black husband. For Fantastic Negrito, that discovery was transformative. “I felt like my ancestors were tapping me, like, ‘Hey man, we’ve got this amazing story. We’re not on the left. We’re not on the right. We’re not entrenched in some ideology. We’re just two people from the opposite sides of the spectrum who found love together at a time when that was impossible.’ I am the result of that, seven generations later. I didn’t know who I was, but I guess I am exactly who I need to be.”

Fantastic Negrito - White Jesus Black Problems (Full Film)

On record, Fantastic Negrito’s main guitar foil is Japan’s Masa Kohama. When Kohama auditioned for the band, he could barely speak English and Fantastic Negrito was skeptical. He thought, “‘This is going to be quick. Let’s audition.’ And he blew me away. I was like, ‘Wow, maybe I was being prejudiced?’”

That story and the accompanying awe that sprang from unearthing his roots permeate his latest release, White Jesus Black Problems. But it’s not just an audio album—it’s a visual work of art that combines many of the songs’ videos into a seamless, Broadway-like production that’s essentially a companion film for the 12-song record. Both are a rich, high-energy explorations of identity, race, love, determination, freedom, and history.

But there’s another level to Fantastic Negrito’s artistry—something he wrestles with, ironically, because of his fabulous success. Winning a Best Contemporary Blues Album Grammy for each of his last three albums left him with a conundrum: Should he give fans what they expect or forge ahead with his constantly evolving musical vision, wherever that may lead?

“I always start by myself. I have an $89 Rogue bass—it’s like an old violin bass. I start out on that a lot of times.”

He chose the latter. “I am going to answer to the music,” he says. “You can’t win three Grammys in a row and then not push to make something that’s outside the box, something that’s brave, outrageous, bombastic. It was like my grandparent’s story. That story’s real, and that meant the album had to be out there—as far as I could push—because my grandparents are obviously out there. You have to push the boundaries of your creativity and challenge yourself sonically, and that’s what’s exciting about this album: It’s how uncomfortable it is. The artists that I loved were always the ones that were a little uncomfortable. You hear the record and think, ‘Is it okay that this is happening?’ I always strive for that.”

White Jesus Black Problems oozes catchy melodies and is eminently singable, although it’s anything but conventional. It starts with “Venomous Dogma,” which eschews the standard verse/chorus formula and feels almost through-composed, morphing trippy psychedelia into a heavy, riff-centric romp.

“That song was fun,” Fantastic Negrito says. “I wrote that and thought, ‘My grandmother must have been a little girl in Scotland when, one day, boom, now you’re an indentured servant for seven years. What the hell?’ The tumultuous energy in that song—complete bliss turning to complete hardship, which must have been the same for my grandfather—I wanted to tell that story and capture that energy. It was very cathartic and that’s why it does what it does.”

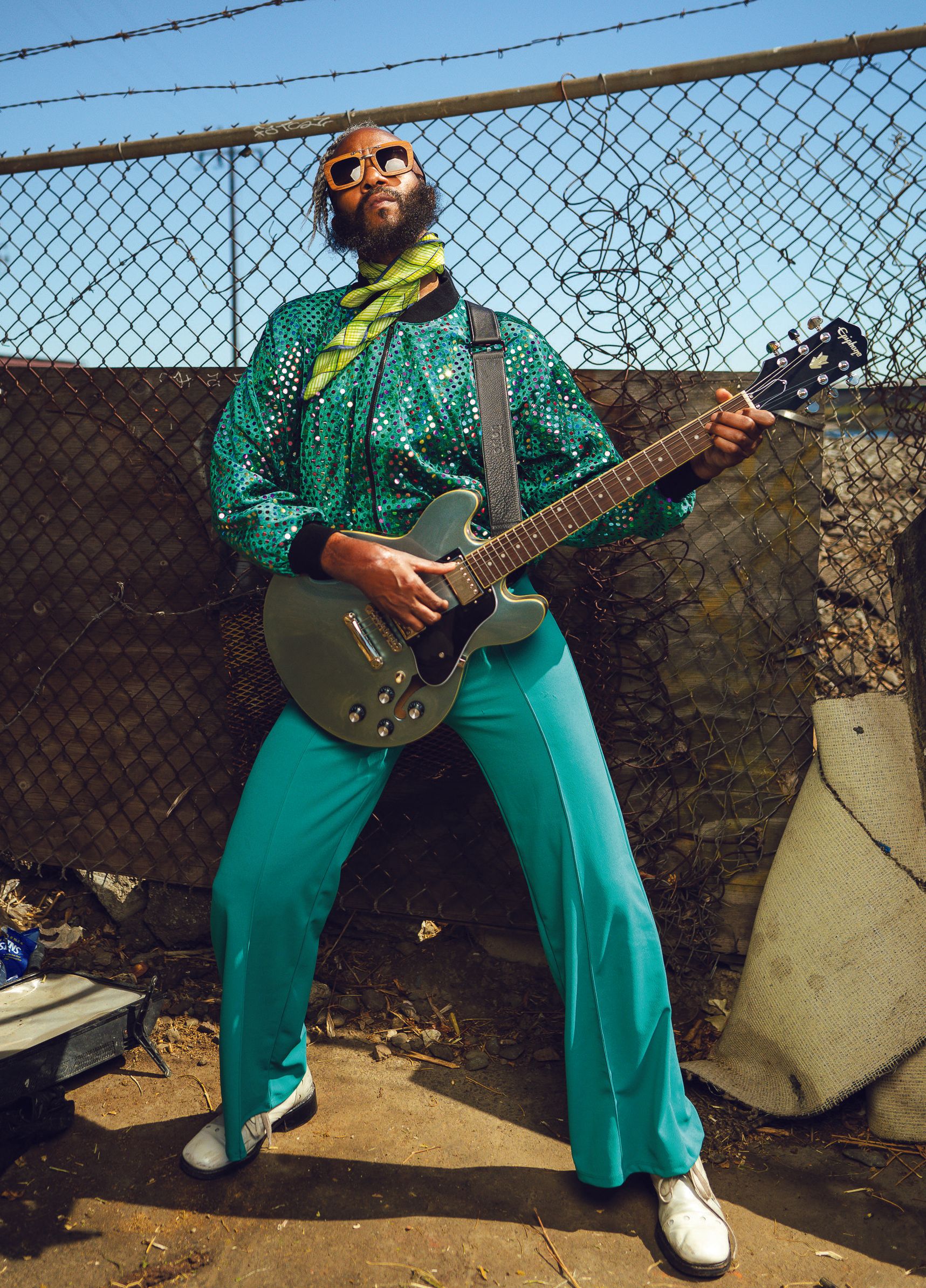

While this Epiphone Dot wasn’t on the new album, Fantastic Negrito’s Epiphone Masterbilt Zenith was one of his go-to instruments for the sessions.

Other songs on the album, like the funky “Highest Bidder,” or “Trudoo,” which owes something to classic P-Funk (or maybe Prince), go in a very different direction. The same is true for the doo-wop feel of “Nibbadip” and the ’70s-era riffage of “Oh Betty” and “Man with No Name.” Yet White Jesus Black Problems feels cohesive because its story has twists and turns of the sort we encounter in real life.

“With me, it’s completely organic,” he says. “A song could start out with a beat that I clap, or a groove, or a poem, or with a guitar or piano or bass. I have no routine. The routine is to let the song write itself, let it happen. Tune into this channel—this frequency of the universe—and let it happen. Maybe most of it’s not great, but 10 percent of it may be pretty good, and that’s when you tell the story.

“One of the most important things to me as an artist or songwriter, regardless of genre—roots, Americana, the blues, whatever—is the stories the songs are telling. That’s it. Really. That gets lost, the stories, but it’s about the stories. People needed those stories to keep making it through the generations, whether it was bondage, Jim Crow, segregation—they needed the story, the music was the medicine. There’s a reason why African-Americans created all this music—all these genres for the whole world to enjoy: They had to survive some of the most challenging situations in this country, and the music has all that feeling because people were trying to save themselves.”

“I can’t paint these pictures without these other musicians. They have completely different tastes than I do, too, which is good.”

Part of keeping it organic is making sure he’s always prepared for when the muse strikes. Fantastic sleeps with an Epiphone Masterbilt acoustic-electric next to his bed and always has an iPhone on hand to record ideas when they hit. “I am full of ideas,” he says. “I wake up in the middle of the night—I live on a farm—you walk out and clean out the chicken coop and then, ‘Oh no! I got something!’ I always have my guitar. That Epiphone is a good friend. It’s fed me and my tribe.”

When he gets to the studio, he scrolls through the audio files on his phone, picks out the gems, and presses record. “I always start by myself,” he says. “I have an $89 Rogue bass—it’s like an old violin bass [the instrument makes an appearance in the video for “Venomous Dogma”]. I start out on that a lot of times. I start tracking, lay down everything, and then I get the boys in, because I am really a songwriter first.”

But he’s also an arranger with a keen ear for orchestration and interwoven parts. Layers of guitars—and an occasional Minimoog—weave their way in and out of the various songs off White Jesus Black Problems. And once a song starts taking shape, his artistic vision is crystal clear. “That’s what makes the records go fast and easy,” he says. “But I can’t paint these pictures without these other musicians. Their contribution is massive and I give full credit to them, always. They have completely different tastes than I do, too, which is good.”

Fantastic Negrito’s Gear

Fantastic Negrito atop his preferred amplifier, an Orange TremLord 30, with a P-90-stocked Chapman T-style.

Guitars

- Epiphone Masterbilt Zenith acoustic-electric

- Gibson Les Paul Signature semi-hollow goldtop

- Chapman ML3 Pro Traditional

- Gibson Hummingbird

- ESP 400 Series T-style

Strings

- DR Strings .009 sets

Amps

- Orange TremLord 30 combo

Effects

- EarthQuaker Devices Sea Machine V3 Chorus

- EarthQuaker Devices Park Fuzz Sound

Masa Kohama plays lead guitar on almost every track on the album, while he and Fantastic cover rhythm-guitar chores together. They’ve been a guitar team for almost 25 years, since a young Xavier Dphrepaulezz first signed to Interscope Records (as simply Xavier) for his ill-fated first outing with a major label, 1996’s The X Factor.“

I was looking for a guitar player who could play all the different styles that I play and, boom, here comes this Japanese guy who can barely speak English,” he remembers. “I thought, ‘This is going to be quick. Let’s audition.’ But he blew me away. I was like, ‘Wow, maybe I was being prejudiced?’ I didn’t expect that from him. He’s such a great player, and I’ve never made a record without him.”

The pair gets together to write and bounce ideas off one another in the same room at least once a year—Kohama is still based in Japan—and they share files across continents the rest of the time. But after so long, their natural synergistic relationship is at a point where they know what to expect. “We can read each other’s minds. Absolutely. He knows and I know, and that’s how it goes.”

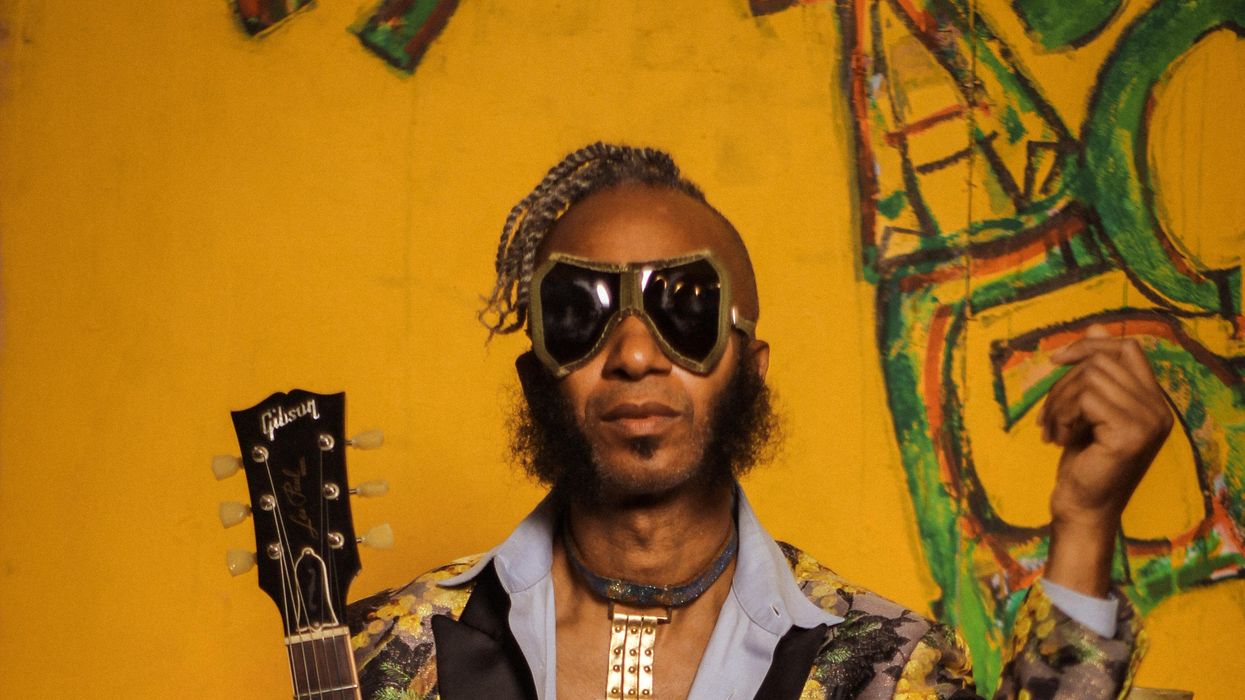

Fantastic onstage with a slope-shouldered Epiphone Masterbilt dreadnought.

Photo by Debi Del Grande

Kohama doesn’t tour with Fantastic, though. That job is filled by Tomas Salcedo, who’s been on the road with the group for years. He’s also the guitarist you see in most of the live clips and videos. He makes an appearance on White Jesus Black Problems, too.

“I always let Tomas get on the records, and he brings something different than Masa,” Fantastic Negrito says. “He’s on the song ‘Virginia Soil,’ and I needed him on that song because he does less a lot, and that’s amazing. That song is empty, open, beautiful, and a lot of it is breathing.”

Fantastic’s affinity for “less” applies to his tonal approach, as well. He primarily uses just a guitar, an amp, and mics. Pedals are not a big part of his sound—although he does have two EarthQuaker Devices units, a Sea Machine V3 Chorus and a Park Fuzz Sound, that sit on his mixing console for use in post-production. But for the most part, he records guitars clean.

“I tell Masa to play completely dry. No effects. I say, ‘Even play direct if you have to,’ because then you can reamp it. Or you can use board distortion. I love that—where you’re just pushing it from the board. I’ll use the mics that are in the piano to catch part of the guitar. I love reamping. You can be more creative and get more interesting sounds.”

But, again, those great sounds, those recording techniques, and that gear are just tools for conveying the all-important stories, whether they’re about reaching majestic heights or sinking to painful lows—like the debilitating car accident that put Fantastic in a coma for three weeks and cost him both his first record deal and much of the use of his right hand. That he rekindled his will, stormed back from career death, and can still lay down an infectious guitar groove makes him a bona fide inspiration. Perhaps it’s because he never ceases looking for inspiration from something he feels was always embedded within him.

“I hate to keep talking about my seventh-generation grandparents, but it’s from them,” he says. “You find a way. The most challenging situation, the most insurmountable odds were against me to play again, but I found a way. I figured out all this came from these people—these incredible people who lived in the 1700s. I feel there’s something about DNA and blood, and I always had this attitude that no matter what, we can do it. And that’s from them.”

Fantastic Negrito performs a short acoustic set and talks about the family history behind White Jesus Black Problems at South by Southwest 2022. Note the technique he has developed with his accident-damaged picking hand, which he calls “the claw.”

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.