The old English proverb “birds of a feather flock together” has been around since the mid 1500s. Clearly, the meaning behind this expression informed Rich Robinson when he was filling out the lineup card for the Magpie Salute, the group he informally assembled in 2016 with some of his former Black Crowes bandmates.

“As I tour and play and get older, and my perspective on the world changes, I realize what a gift it is to play with people that you have a connection with,” he attests. “I want to play with people that I have a connection with.” And so, in 2016, that “connection” led Robinson to reach out to several former members of both the Black Crowes and Hookah Brown (the short-lived ensemble he put together in the early part of the new millennium) with an invitation to record an album live, in front of a studio audience, in Woodstock, New York.

Among those who showed up was Robinson’s former guitar-mate in the Black Crowes, Marc Ford. “I reached out to Marc’s agent and manager, because we hadn’t spoken much in the last 10 years,” recalls Robinson. (Ford left the Black Crowes for the second time in 2006.) “I was like, ‘Does he want to come and do this?’ And his agent said, ‘He doesn’t care what it is, he wants to come.’ I thought that was a cool step, for both of us, towards healing whatever kind of weirdness there may have been. I think Marc and I had a similar arc after the Crowes, and it gave us the perspective that we wanted to get back together.”

That first performance, which took place during a Rich Robinson solo tour in support of his Flux record, eventually morphed into what is now the Magpie Salute—a band forged from the same swaggering, blues-rock template as the Black Crowes, albeit with broader musical aspirations and without the interpersonal drama that caused the aforementioned weirdness. The Crowes ceased operations in 2013, and officially called it quits in 2015 as the result of an irreconcilable rift between Rich and his older brother, the band’s lead singer, Chris Robinson. “It was very cliquey, and I was younger than everyone else,” he explains. “Chris was angry all the time and didn’t want to share credit. It was divide and conquer.”

As he reflects upon his time in the Crowes, he realized that he spent a lot of time with his bandmates, but he didn’t really know some of them. “It’s interesting to spend so much time on a bus with someone and spend every day with someone and not really have much of a personal relationship,” he says. With the Magpie Salute, Robinson intends to rectify that.

The self-titled debut album that resulted from that first Magpie Salute performance/session, which took place at Applehead Recording, a studio located on a 17-acre farm in Saugerties, New York, represents a cross section of the musicians’ shared past and collective influences, including some deep Crowes cuts along with covers of Delaney & Bonnie, Bobby Hutcherson, War, and the Faces. In addition to Ford, ex-Crowes members Sven Pipien (bass) and Eddie Harsch (keyboards) were there and eager to reconnect, too. Afterwards, there wasn’t any intention to do more, but, at the behest of Harsch, Robinson booked three nights at the Gramercy Theatre in New York City. “I was like, ‘Okay, we’ll put a show up for sale and see what happens,’” he explains. “Gramercy sold out, so we put up three more, and they sold out, and then it was like, ‘Hey, let’s do a tour, and while we’re at it, we recorded that album last year—let’s put that out.’ It was just one step after the other. We didn’t form a band, go into the studio, make a record, go out and tour on it. It was less thought through than that, but there’s an authentic element to the whole thing.” Eddie Harsch, unfortunately, never made it to those shows, because he passed away unexpectedly in November 2016, and Matt Slocum, from Robinson’s solo band, has since taken up keyboard duties.

The “authentic element” that had been evident to Robinson since the Magpie Salute’s inception has actually been a vital component of his playing ever since he burst onto the scene with the Black Crowes in 1990 on their debut album Shake Your Money Maker, which peaked at No. 4 on the Billboard 200. Two of its singles, “Hard to Handle” (an Otis Redding cover) and “She Talks to Angels,” reached No. 1 on Billboard’s Mainstream Rock charts. Steeped in the blues-rock tradition of bands like the Rolling Stones, the Faces, and Humble Pie, the Black Crowes sounded rough and spontaneous compared to their often-over-produced contemporaries. They didn’t really fit neatly into the musical zeitgeist of that period. They were neither an ’80s hair band nor a Seattle grunge band. A small gap in musical movements in the early ’90s provided them with an opportunity to grasp listeners with their commanding Brit-meets-Southern-rock vibe.

The Black Crowes’ sophomore album, 1992’s The Southern Harmony and Musical Companion, was the band’s first release to feature Marc Ford, and it reached the top spot of the Billboard 200 albums chart in 1992. It spawned four No. 1 hit singles, including “Remedy,” “Thorn in My Pride,” “Sting Me,” and “Hotel Illness.” In Ford, Robinson seemed to have found the perfect foil for his open-tuned style of guitar playing and songwriting. It’s a pairing not unlike Ron Wood and Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones, or Malcom and Angus Young of AC/DC—players whose ability to influence one another and interweave parts appears seamless and completely symbiotic.

“No matter what was happening with our personal lives, Marc and I would go onstage and it would just sound that way, and that was really amazing to me,” admits Robinson. “The first day we ever started playing together was the first day we started recording Southern Harmony, and there’s always been this musical connection there.

TIDBIT: The band’s new album is its first studio production of original music. “We didn’t form a band, go into the studio, make a record, go out and tour on it. It was less thought through than that,” says Robinson.

It’s one of those things that’s kind of inexplicable—the two of us just go to this place together.” So while they may not have had a deep personal connection yet, they clearly had a musical one, and went on to record two more epic albums together, Amorica and Three Snakes and a Charm, before internal strife forced Ford’s departure.

Ford got his professional start in the blues-rock band Burning Tree in 1990. He joined and quit the Crowes twice in the ensuing years. In between his Crowes stints, he released solo albums, played with Ben Harper and Izzy Stradlin (Guns N’ Roses), and produced other artists, including PawnShop Kings and Ryan Bingham. Robinson, looking for peace and clarity amidst the chaos that became the Crowes, released a few solo albums and formed Hookah Brown, which featured current Magpie Salute lead vocalist John Hogg.

Last year, when Robinson first took the Magpie Salute out on the road, they went as a 10-piece, based simply off the template of what they had done at Applehead. “We had two keyboard players, three guitar players, Sven and Joe (Magistro, drums), and I brought in a couple of singers and had this brilliant musician, Karl Berger, who played vibes and piano.” Hogg officially became lead vocalist when Robinson decided to scale things down and go with a more traditional rock/jam band format of two guitars, bass, drums, and keyboards.

The Magpie Salute recently released their sophomore effort, High Water I. While the first singles, “For the Wind” and “Send Me an Omen,” will draw striking comparisons to vintage Black Crowes, it’s songs like “You Found Me,” “High Water,” and “Walk on Water” that demonstrate the range of influences at work within the band’s musical framework. From Americana to jam to Southern rock to psychedelia, Robinson, Ford, and company are tapping into a well of musically diverse influences and churning it into a sound that embodies their organic approach to songcraft. The playing sounds off-the-cuff and of-the-moment—neither the tunes nor the guitar solos seem overly devised. Rather, the musicians communicate on a level that makes High Water I sound alive and honest, which is refreshing, especially, in an age when technology can subjugate the simple act of someone playing an instrument. Simply put, the Magpie Salute may be a new band, but it’s got an old soul. PG caught up with Robinson and Ford, just as they were about to embark upon their first official North American tour as a six-piece, to talk open tunings, creative philosophies, guitars, amps, and production techniques.

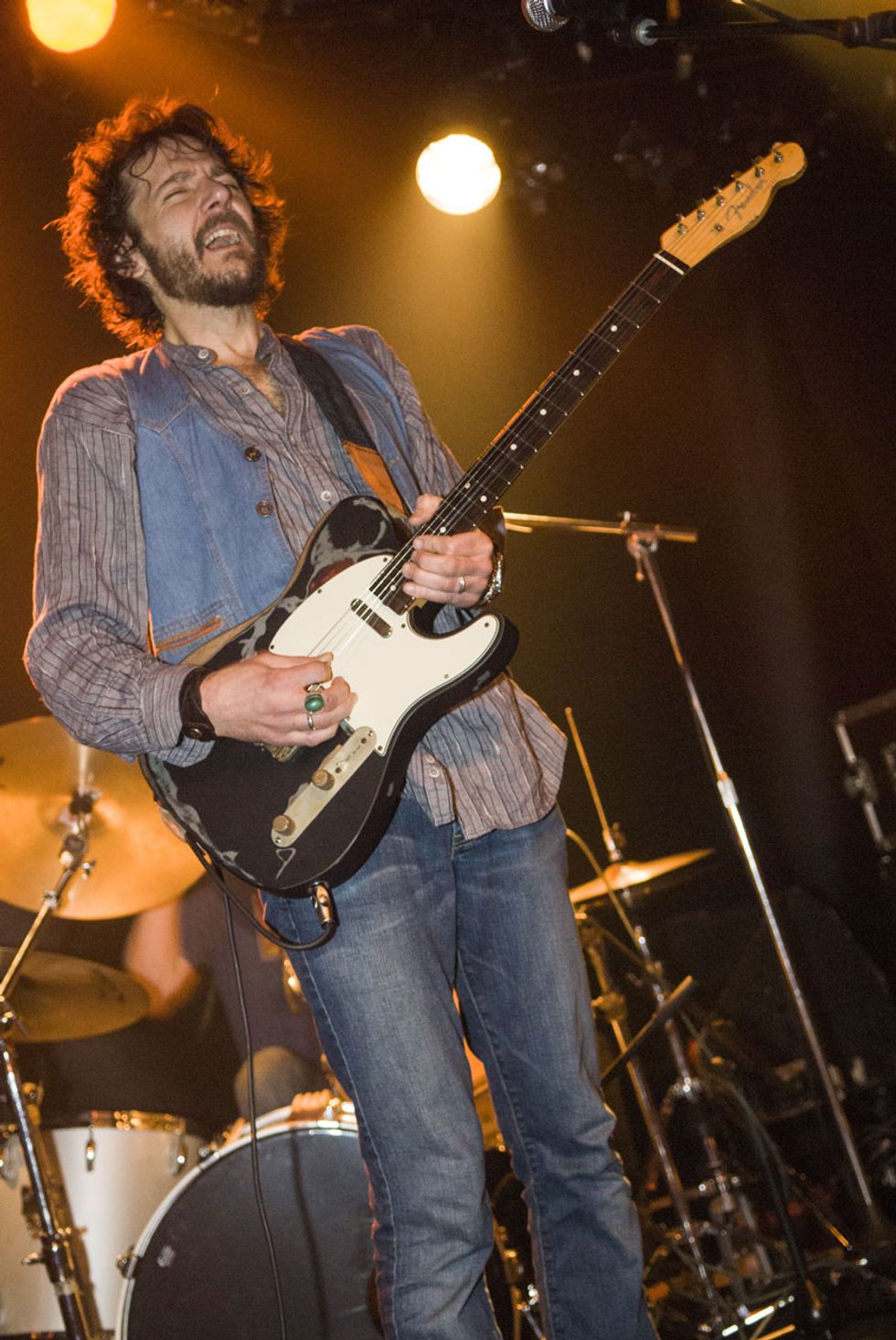

On a pre-High Water I tour, Marc Ford digs into a custom-finished Fender Telecaster. About practicing guitar, he says, “At this point, I’ve put in the hours. I’ve held the thing enough in 42 years that my body is actually deformed from it.”

Photo by Jordi Vidal

The Magpie Salute recorded a live album and did some touring before committing to an album of all original material. Was there an advantage to playing live first, versus making the album, and then touring?

Rich Robinson: That definitely gave us an advantage, but what I like about the whole thing is everything was just organic. We got together for those shows in Woodstock in 2016, which was cool. And that was all it was going to be. I went on and finished my solo tour and Marc went on and did his thing and Ed went on and did his thing. So, it was never meant to be anything other than that. But we all felt something really special in that studio when we were playing.

Many of the guitar solos on High Water I, especially on songs like “High Water” and “Mary the Gypsy” sound unscripted—like an exploration, like you’re searching for something.

Marc Ford: That’s exactly what it is. That’s the organic bit of it—be brave enough to stand in any situation and respond to the circumstances. I’d never heard “High Water” before. Rich brought it in that morning and I was like, “Wow! That is bitchin’!” And he handed me a guitar that I never played before and was like, “Go for it.” And that was my response in the moment. I did it one time. If I’d sat and thought about it, I would’ve driven myself crazy and nothing would’ve happened, probably. Eventually you get so used to looking like an asshole that it doesn’t scare you anymore [laughs], and therefore you’re brave and you get fearless. And we all know that the most beautiful things come from these accidents where you’re really saving yourself from total disaster.

you get fearless.” —Marc Ford

It’s refreshing to hear someone play with such abandon on an album. It’s very old school.

Robinson: That first solo on “Mary the Gypsy” is Marc. I think one of the first things he played on Southern Harmony was the solo on “Sometimes Salvation,” and it was one take and he was fucking winging it and it’s brilliant. Marc still has that fire. And this whole record is that. The songs are that and that’s what’s amazing about this band. It has that abandon, like “Fuck it, let’s just do this thing.”

The songs do seem like moments captured in time and that you guys will, maybe even intentionally, never play them the same way again.

Robinson: I’ve never done months of preproduction, because the way that I work, and the way that I think we work best, is off the cuff. It’s more about feeling, instead of obsessing over a part that you’ll play exactly the same way every time you play it. It’s always been about the excitement that comes from that moment of creation. Rock ’n’ roll is supposed to have an abandoned quality, like all shit could go wrong at any moment, but when it doesn’t, it’s brilliant.

Guitars

Asher with Curtis Novak pickups

Asher Marc Ford Signature Model with Jason Lollar P-90s

Asher prototype signature model

Gibson Les Paul

Gibson Firebird

Fender B-bender Telecaster

Gretsch Falcon

National resonator

Satellite Coronet

James Trussart Steelcaster

Danelectro 12SDC 12-string

Gibson J-150

Gibson Dove

Martin D-35

Martin D12-28 12-string

Amps

Satellite Cuda

Satellite Gammatron

Satellite Scamp

1970 Marshall 50-watt

1968 Fender Bassman

Fender Deluxe Reverb

Magnatone Twilighter

Effects

Analog Man ARDX20 Dual Analog Delay

Analog Man-modded MXR Phase 45

Analog Man Sun Lion Fuzz Booster

BMF Wah

Catalinbread Belle Epoch Deluxe CB3 Dual Tape Echo

Fulltone Tube Tape Echo

Satellite Eradicator

Satellite Fogcutter

Satellite My Pal Fuzz

Satellite White Amplifier Emulator

Strings and Picks

“Whatever Rich was using.”

You could say the album is organically psychedelic in that way.

Ford: Yeah, we’re not trying to trip you out; we’re just playing this really bitching stuff. And we’re discovering this record just like everyone else. It’s just pure joy to discover this record. Like “Sister Moon,” for example: It’s an incredible song and I don’t even play on it. I love it and I’m not on the thing. I learned a little while ago that, really, it ain’t about me.

How do you guys split your guitar duties?

Ford: For the most part, whoever brings in the block of the engine dictates mostly what’s going on. But there have been instances where Rich brings in a song and I end up playing his part and he ends up making up another part—however it works out, that’s why it’s so much fun now. We don’t have anything to prove [laughs]. This is pure gravy. This is the shit. We’re free to do whatever we want to and not be fearful of being competitive or about what anyone’s thinking. We’re all for one, one for all—the greater good. It’s really a pleasurable experience and I think the music is showing it.

Marc, I understand that you don’t necessarily practice the guitar anymore. Can you clarify that?

Ford: At this point, I’ve put in the hours. I’ve held the thing enough in 42 years that my body is actually deformed from it. I don’t need to practice anymore. I need to stretch and limber up, like anybody does. You don’t want to go bowling without bending over a couple times. But now I do the things that mentally and physically and spiritually allow me to be able to go to the places I want to go. I want to keep myself open to be able to learn and experience new things at all times, and I can’t do it continually sitting and doing the same thing I’ve done over and over and over in my life. I learn much more about guitar by doing something else, like watching somebody paint a picture or going down to the beach and watching people surf, than I do by practicing anymore—because it’s not really on a physical realm. It’s all outside.

Marc, a moment ago you said it ain’t about you. So how do you keep your ego out of the creative process?

Ford: You put out your arms and you try to catch it the best you can, but it’s going to show up the way it wants to show up and it tells you how it wants to be. This music that is made when Rich and I get together … it wants us together, because it’s only made when he and I get together. It’s incredibly humbling to be part of something that requires more than yourself and is special to that relationship. You need to steward the relationship so that the gift can come out. The stewardship part of me now is to keep my heart and my mind open and my spirit open. My hands know what to do.

How do you keep your mind, heart, and spirit open?

Ford: Keeping a clean house [laughs]. Going through rehab stints will teach you, seriously, like, “You better check your shit out before you say a word about anybody else’s thing.” It’s better just to shut up and get going with it. Unforgiveness will fuck you up. And taking offense—you’re locking yourself up. You just gotta get over it.

Watch the band's Rig Rundown from 2017

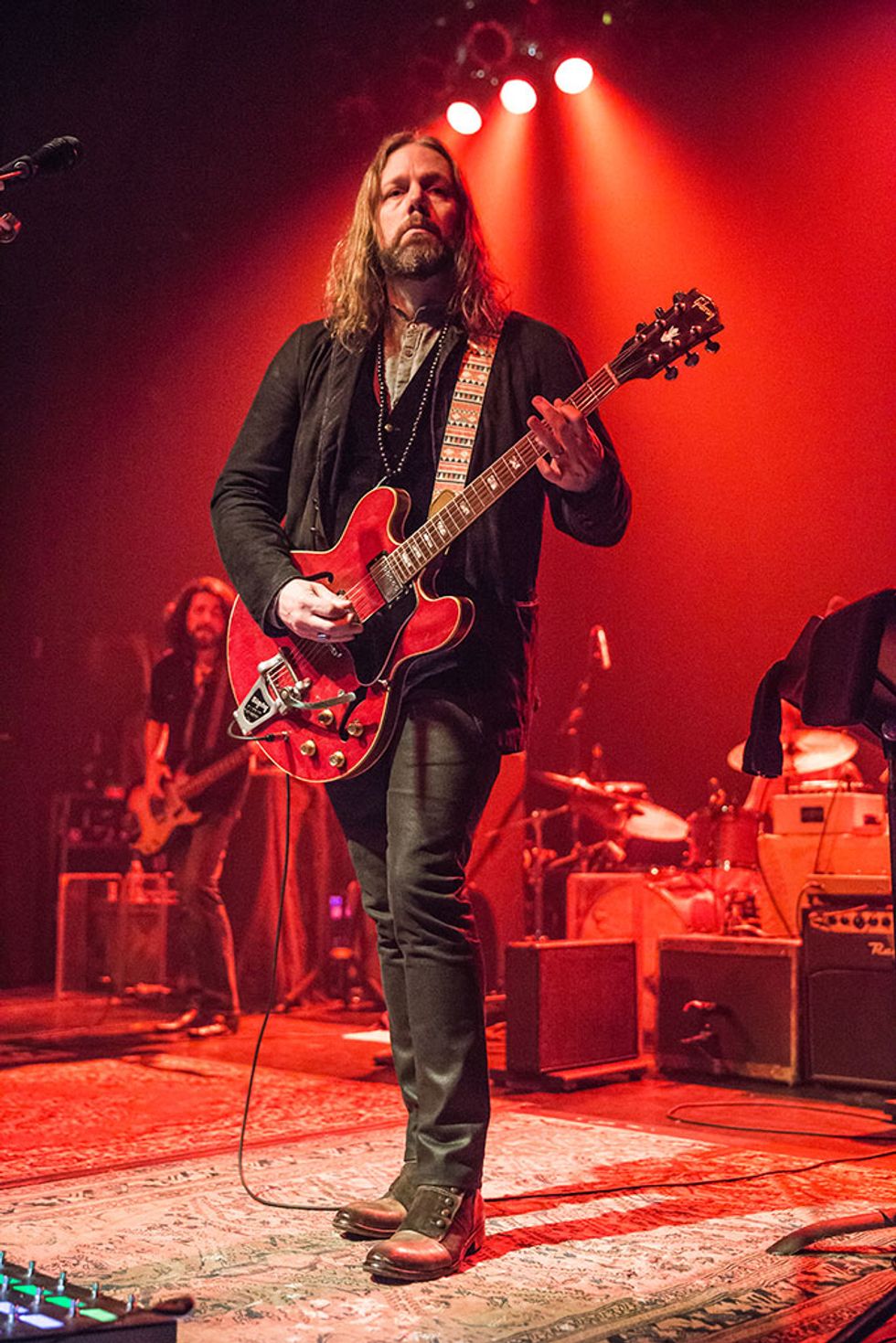

Robinson performs on one of his longtime standby instruments—his 1967 Gibson ES-335. Stephen Stills, Jimmy Page, and Nick Drake are among the players who’ve inspired him to use the open tunings he employs on it. Photo by Joe Russo

Rich, you write a lot of songs in open tunings. Is that a Keith Richards/Rolling Stones influence?

Robinson: It actually comes from Stephen Stills and Nick Drake. I love the Rolling Stones, don’t get me wrong, but as far as playing in open tuning, Keith kind of held onto that 5-string, single-barre-chord sort of element. I listened to what Stephen Stills did and what Jimmy Page would do or Nick Drake in particular—the first time I heard that sound coming off his guitar, I was hooked. I was blown away. The way the guitar sings when the instrument is tuned differently. “High Water” is a rock ’n’ roll take on Nick Drake. I’ve really tried to incorporate his way of playing and writing into a lot of the songs I’ve written over the years.

Do you hear song ideas in your head in open tuning or does fiddling around on the guitar in open tuning instigate the idea?

Robinson: Playing in open tuning influences the idea. It’s because of the timbre of the guitar and the way it sounds with those open strings. I find the vastness of a chord within that tone—you can let everything hang out with the open strings and that’s what excites me.

What was it about Stephen Stills that drew you in?

Robinson: One of my earliest memories was listening to “Carry On”—my dad loved Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young—and listening to the way he played “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes.” All of that was ingrained in me from the time I was born. I always loved the way Stills played. I just thought it was phenomenal. I also remember touring with Jimmy Page, and he showed me the tuning he had for “The Rain Song” and it was just so brilliant. Or listening to Bert Jansch and what turned out to be Jimmy’s “Black Mountain Side,” but Bert Jansch’s version of that [“Blackwaterside”] was just fucking amazing—trying to get around on DADGAD. It’s interesting to tap into and be able to mess around with these tunings and go from there.

Do the characteristics of your guitar choices equally influence the songs and what you’re playing?

Ford: The fun part for me is that I never used Gretsch guitars before, except maybe a little bit here and there, but on this record, I used the hell out of Rich’s Falcons and I loved it. Like a Fender or a Gibson, you just play it different. It holds you different and your angle on it is different. The scale length and all that can be exactly the same, but it’s still got another attitude. The character of the guitar really dictates the part I’m playing. I didn’t set up the guitars for me. They were Rich’s guitars. They have heavier strings than I normally use. It keeps me focused on the songs and what’s needed aurally, not what’s needed in a gymnastic sense. I get to sing, rather than jump through hoops.

What were your signal chains for recording?

Ford: For the record, my go-to amp, unless I specifically needed a particular sound, was my Satellite Cuda. It’s basically a 50-watt Marshall—that’s the most basic way to describe it. And it’s stellar. And it almost always works with the track. If it wasn’t that, it was another Satellite. And then we had a great version of a Fender Deluxe and a great version of a Bassman and a great Marshall. We had all Rich’s gear there. A fantastic version of a Telecaster. Anything you’d need was there. So, the only things I brought were a couple of Ashers and these Satellites that I’m loving. And for the most part, it’s pick a guitar and go directly into the amp. That’s essentially how we did most things. If we needed something else we would plug it in, but a lot of it was us, just going direct in—everything was working so nice.

Guitars

Gretsch White Falcon (custom) with TV Jones pickups

Gretsch Black Falcon

1967 Gibson ES-335

Fender Custom Shop Telecaster

Fender Custom Shop Stratocaster

Gibson Dove

Eastman acoustic guitars

Martin acoustic guitars

Amps

Reason RR Signature 50 Amp

Marshall Silver Jubilee

1971 Marshall JMP

Harry Joyce Custom 50

Fender Bassman

1959 tweed Fender Vibrolux

1960 reissue silverface Fender Deluxe

Vox AC30 Handwired

Reason SM25

Edmond 4x12 cab

Reason 2x12 cab

Effects

DOD FX96 Echo FX Analog Delay

Fulltone Tube Tape Echo

Van Amps Reverbamate

Way Huge Electronics Angry Troll Linear Boost

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXL140 Light Top/Heavy Bottom (.010–.052)

D’Addario EJ16 Light (.012–.053)

Dunlop Tortex .73 mm

Robinson: I’m mixing and matching guitars and amps depending on what I feel the song needs. If Marc is playing a Les Paul or a humbucker or a heavier sounding guitar, I’ll tend to go light and choose a Tele or a Strat or something that would work well with the sonic quality of whatever he’s doing, and vice versa—Marc would do the same with me. We’re always thinking about those elements and using certain amps. We had 15 or 20 amps that we were choosing from while we were recording. Some were ’50s Fender Vibrolux single 10" amps and my 1971 JMP 50-watt Marshall running through a Harry Joyce cabinet. I have my Silver Jubilee head that I used on Shake Your Money Maker, Southern Harmony, and Amorica. We also had some AC30s, some Reasons, a Bassman, and an old Matchless cabinet that Mark Sampson made for us for Amorica. We were just trying to figure out what worked and what didn’t.

Marc, what were you trying to get out of your Asher signature model when you first came up with the design?

Ford: I met Bill [Asher] when I was playing with Ben Harper in ’03 and ’04. And then when the Crowes did the reunion gigs in ’05, he said, “Let’s build a guitar. What would you want?” And at the time, the two coolest guitars I had were a friend’s ’59 Les Paul Special and a Stratocaster. So, I said, “If we could put these two guitars together, somehow, that would be perfect. Is that possible?” And that was the idea. Over the years it’s morphed into what it is. People have been responding to it because it’s a viable instrument. There are reasons for the appointments and it makes sense to them.

Rich, you produced High Water I. How challenging is it to wear two hats: decision maker versus artist?

Robinson: I produced all my solo records and a couple of the Crowes records, sometimes with Chris. I never felt like I had a problem with self-editing. If something isn’t working, I’ll be like, “Nope, this isn’t right.” And I kind of know when it’s not working. On the flip side, most producers, and I’ve only worked with a few—George [Drakoulias] produced a couple of our records and Kevin Shirley produced one record—tend to go overboard with simplify, simplify, simplify. And I don’t believe in that.

Can you clarify what you mean by that?

Robinson: Bass is one of my favorite instruments. I think it can add so much color and melody and movement to a song, but for some reason in the ’80s some dude had success by telling the bass player to just ride the root note and play the kick drum pattern. And then, all these producers got in line with that, as if it made them sound knowledgeable or something. But I’m like, “Did James Jamerson do that? Did John Paul Jones do that? Did Andy Fraser do that?” My favorite bass players play beautiful melodies that really touch on specific elements of the song.

A lot of people will tell you to dumb music down—dumb it down because people are stupid, and they can’t listen to it. But I’m like, “Well, why did they like the Beatles? And why did they like the Rolling Stones and Simon & Garfunkel and Sly Stone?” Sly Stone was not fucking simplistic. Some of the shit that guy was doing was so intense and beautiful. So, in my opinion, it came down to turning music into a toaster oven or a vacuum cleaner just to sell it. Basically, turning it into McDonald’s—the most basic form of food that everyone will like, and you can sell a lot of.

So, what is your approach to producing?

Robinson: My approach is to let players play. Like, “What would you guys do? You have all the ability in the world, now, after playing for 30 years. Play like you’re 21 years old. What would you do with all of this ability and you’re 21 years old?” Everyone knows not to overplay [at this point]. I mean, you’re a good enough musician not to just fucking go in there and spray dayglow paint all over everything, but I think that excitement and intention is still at the core of it.

The Magpie Salute proudly airs their classic-rock influences with this live version of Led Zeppelin’s “Custard Pie,” from late 2017 at the Warehouse at FTC in Fairfield, Connecticut. Now, the band is trimmed down to a six-piece on tour.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)