Sometime in the mid ’70s, Roger Waters, the leader of the progressive rock band Pink Floyd, began to feel a wall developing between the group and its stadium audiences—who were increasingly rowdy and beer-swilling, and seemingly indifferent to the music. This sense of alienation served as the inspiration for Floyd’s epic 1979 double album, The Wall—a rock opera that also addressed some of the other difficult personalities in Waters’ life, including abusive schoolteachers (“Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2”) and an overprotective parent (“Mother”), among others.

Despite its derisive tone, The Wall earned Pink Floyd even larger audiences. A decade after the album was released, more than a quarter of a million fans saw a live concert of the album in its entirety in Germany as Waters and guests like Cyndi Lauper, Van Morrison, and Joni Mitchell celebrated the fall of the Berlin Wall. Now, 20 years after that historic concert, and 30 years after the album was released, Waters has embarked on an ambitious worldwide tour: The Wall Live is playing before packed houses from Toronto to Manchester, England, until June 2011. The mammoth tour features some killer guitarists: former Saturday Night Live mainstay G.E. Smith, Dave Kilminster (known for his work with legendary keyboardist Keith Emerson), and Snowy White, a British instrumentalist steeped in the blues.

White, now 62, got his start as a professional guitarist in early 1970s London. Thanks to his tasteful playing—and to being an affable bloke in general—he made a name for himself on the UK scene without great difficulty. White’s first big gig was a stint as an auxiliary live guitarist for Pink Floyd in the late 1970s, followed in the early ’80s by a slot in the rock band Thin Lizzy.

Since then, White, a consummate pro, has had an enviable career. As a solo artist, he scored a major hit with the 1984 single “Bird of Paradise” from the album White Flames, which is also the name of the band he’s long fronted. At the same time, White has regrouped periodically with Waters for the 1990 Berlin performance of The Wall and for Waters’ 2000 In the Flesh tour, among other occasions. Meanwhile, the Snowy White Blues Project finds White in a more straightforward bluesman mode. “I’m lucky, really—I’ve got both worlds here,” he says.

We met up with White in the lobby of a swanky hotel in Manhattan’s SoHo district—which is, appropriately enough, a neighborhood rife with guitar history—to talk about everything from the Wall tour to his blues roots.

How’d you get into the blues?

|

What’s the story behind the goldtop Les Paul that has been with you throughout your entire career?

When I was 18 I met a Swedish girl, so I went to Sweden, because that’s the sort of thing you do when you’re younger—you go where the girlfriend is. I got in a band there—a trio called the Train—and the drummer knew somebody who had a Les Paul for sale. I didn’t know anything about guitars at all—and I still don’t—but I wanted a Les Paul. I had a Stratocaster, which I didn’t like, and I swapped it for the Les Paul— an all-original 1957 goldtop. That was in 1969. I’ve had the guitar for 41 years.

Is it still 100 percent original?

It’s a working guitar, and I’m not precious about it, so I’ve changed things when they needed changing. It’s had different machine heads. It’s been rewired. It’s been refretted a couple of times. And it’s got a different bridge, which I put on because [Fleetwood Mac founder] Peter Green gave it to me, even though it was identical to the original bridge. It’s a fantastic guitar, really true in the neck and fingerboard after all these years—and it sings on every fret just as it should. It’s just lucky, really.

|

For about 30 years, my Les Paul was my only guitar, and I never wanted another one. But since I’ve been doing other things, like with Roger Waters, I’ve needed a few guitars. I bought a Strat, which is similar to the black Stratocaster David Gilmour has—I figured I would use that for a couple of songs to get the appropriate sound. And on the last tour for Dark Side of the Moon [2006–2008], I bought a ’57 Les Paul reissue, which felt exactly the same as my old one. I put a tremolo arm on it, because I needed to do a few tremolo bits. I also got an ES-345 from Gibson, which is a really great semi-hollowbody. And I’ve got a Martin acoustic, a D-28 that came straight from the factory—they found a nice one for me. So I have bought some guitars I only use when I’m playing with other people. When I’m doing my thing, I just use my Les Paul.

What amps do you prefer?

I used to use a Fender Twin Reverb, but for many years all I’ve used is the Vox AC30. I switched to Vox because it was more complimentary to the sound of my Les Paul. With Roger, even on big stages, I use an AC30. I’ve got two, and I kick the second one in only for solos—that’s it.

When he was 18 and living in Sweden, White traded a Strat for this 1957 goldtop Les Paul. Ever since,

it has been his main touring guitar for gigs with Pink Floyd, Thin Lizzy, and Roger Waters. The label

on the side of the flight case reads “Snowy’s Baby.” Photo by Snowy White

Are your AC30s new or vintage?

They’re new. The thing with Vox, for me, is that they’re all good—a new one, an old one. As long as it’s been looked after, they’re all great.

Let’s talk about your effects.

I don’t use a lot when I’m doing my own thing, but with Roger I obviously need to use a few bits and pieces. I’ve got this Line 6 M9 stompbox that I’m using for the first time. I can get all my repeats and delays—it’s great and works really well. For my basic sound, I use a little Boss Blues Driver, which gives me a bit of an edge. I haven’t got much else really: an Ernie Ball volume pedal, a Boss OverDrive, and a Boss Rotary Ensemble, and that’s about it.

What about strings and picks?

That’s a really good question, because I have no idea what brand of strings I’m using—it depends on what my guitar techs have. For me, to be honest, all brands sound good. I do know the gauges, though: On my Les Paul, I use a light top and heavy bottom—.010, .013, .017, .030, .042, and .052—since I hit the bass strings really hard. The Stratocaster can’t really handle those heavy strings, so I use a regular light set on that guitar. As for picks, when I was with Thin Lizzy the road crew made some little white ones in the size I like with my name on them— 3000 of them. This was in 1980, and I’ve still got a couple hundred left. But when I’m playing my music, I hardly use a pick at all. Sometimes I don’t even take one onstage with me. With Roger’s thing, I use a pick most of the time.

What was it like as a more or less traditional blues player working with huge rock bands like Pink Floyd and Thin Lizzy in the 1970s?

It’s true that I’m quite a narrow person in my playing. I’ve always been into blues and haven’t really expanded my playing beyond it, because I’m very content to do what I do. But, funnily enough, the original Pink Floyd gig was actually very based in blues when you broke it down. I mean, I could play my sort of guitar in Pink Floyd and it wasn’t out of place. And so I was really pleased when I was invited to be their first augmenting guitar player in 1976. I hadn’t really heard Pink Floyd, because if it wasn’t blues, I didn’t listen to it. So when they sent me the albums to listen to, I was pleasantly surprised. David Gilmour played some really nice guitar and I thought, “Oh, I can fit in here quite nicely. And I think I did. It worked out okay. In a way, things were the same with Thin Lizzy—there’s a lot of harmony guitar work in there, but it’s really mostly blues licks. That was good fun. I very much enjoyed playing the harmony guitar with Scott Gorham. It was a great band with great songs.

White mics his stock, recent-vintage Vox AC30s just slightly off axis with a

pair of Shure SM57s. Photo by Snowy White

How does working with Roger Waters these days compare to playing with Pink Floyd three decades ago?

Musically, it’s very much the same as the original Wall. And it’s quite strange, really, because that was 30 years ago and I’m still playing the same songs. But the songs have a freshness to me—they never get boring. I’ve heard them so many times, and I still look forward to playing them, because even if you have to do the same licks every night, you can still try to get them a little bit sweeter, a little bit more on the button, a little bit nicer. There’s always a little sort of contest there—just try and make it a bit better ever night. I quite enjoy that. When I originally played with Pink Floyd, David Gilmour was very generous, always giving me solos. When I listen to some of the things I did to start with, I hear that I just went for my thing in my solos and didn’t really think about what the song needed. And I must have disappointed a lot of people, because they knew all of the original solos. So nowadays I’ve tempered my approach and think a bit more about the context.

What did you do to prepare for this Wall tour?

I just got out the album and listened through, and it all came back to me. Until we started rehearsing, we didn’t know who was going to play what, especially among the guitarists. We had to shuffle it around a bit, so we each had a reasonable amount to do. Apart from that, it was all fairly straightforward.

What has been like working with guitarists Dave Kilminster and G.E. Smith on the tour?

Dave Kilminster is a great musician. He notated all of Dave Gilmour’s solos and learned them intimately. I really enjoy listening to him nail the solos each night. I’ve never notated anything, by the way. I’ve done a lot of bluffing in my time, and I’ve learned to bluff really well. That or I’ve learned to sidestep really well. G.E.’s great, too. I didn’t know G.E. before this tour, and he’s a fine guitar player. He’s what I call a real musician—he plays all sorts of things and is into all sorts of music. He’s great to be on the road with. He’s got so many stories, and I really enjoy listening to his solos in the show, as well. The thing is, because the show’s so structured and we have our separate parts, we don’t play off of each other very much. But Dave, G.E., and I do listen to, appreciate, and complement each other.

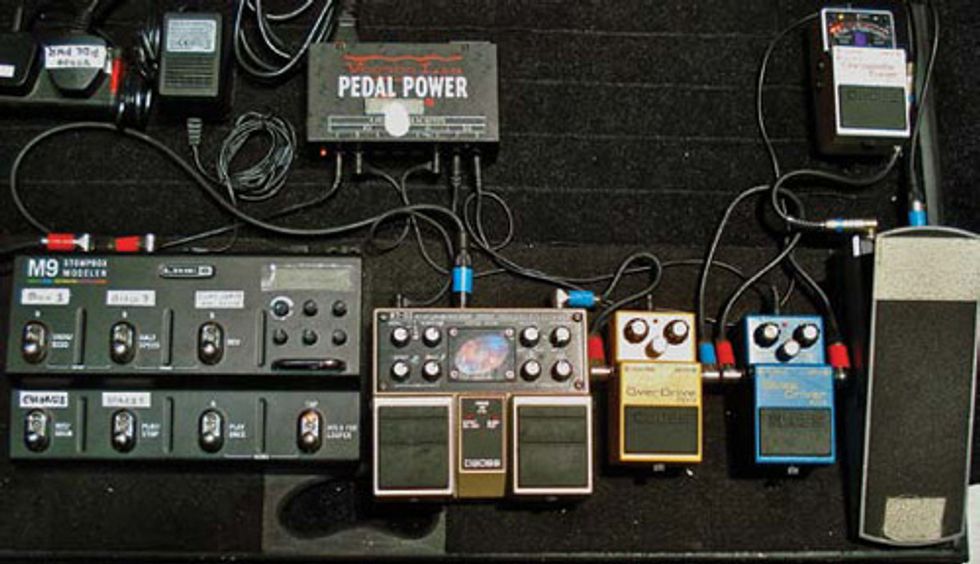

White’s main-stage pedalboard for The Wall tour includes a Boss TU-2 tuner, an Ernie Ball volume pedal,

a Boss BD-2 Blues Driver that he uses for his basic sound, a Boss OD-3 OverDrive, a Boss RT-20 Rotary

Ensemble (used for the solo in “Mother” and other chorusing sounds), a Line 6 M9 Stompbox Modeler (the

“Chorus” switch is for the verse of “Comfortably Numb,” and the “Spaces” switch provides delay for “Hey

You”), and a Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2 Plus. Photo by Snowy White

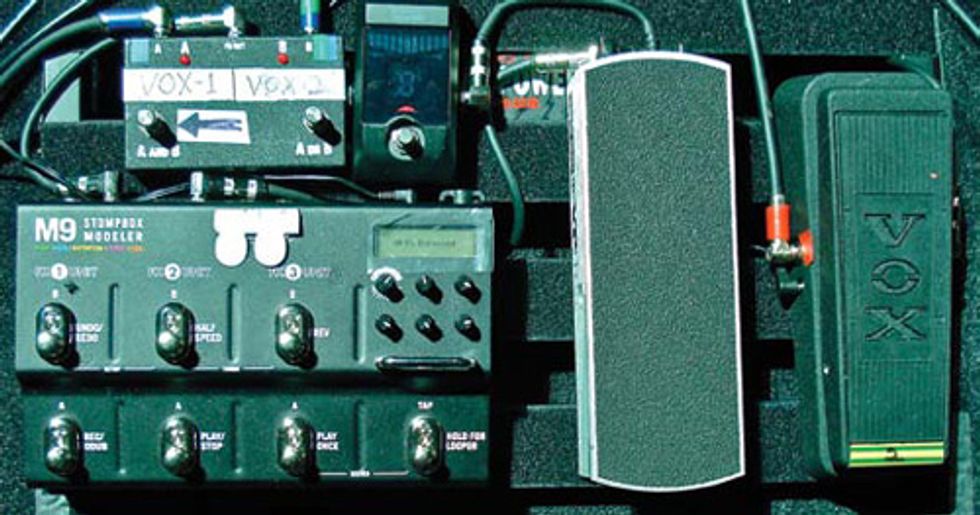

White keeps a separate pedalboard on the front stage of The Wall production. It features a Vox 845 wah,

an Ernie Ball volume pedal, a Line 6 M9 Stompbox Modeler, a Korg Pitchblack tuner, a Morley ABY switch

that selects between his two Vox AC30s, and a Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2 Plus. Photo by Snowy White

Tell us about some of your other projects.

In between working with Roger and the other odd things that come up, I do my own thing. I’ve had a band for a number of years called the White Flames. We’ve recorded about 12 or 13 albums, and we go out around Europe a bit. We’ve got a new album coming out in February called Realistic. For another project, a lot of people told me they’d like to hear more basic blues. So I thought, “I’m not a blues singer, but I’ll get a few people together and get some good vocalists and I can just sit back and play guitar a bit.” I was lucky to get Matt Taylor in there, who’s got a great voice and is a great guitarist, and Ruud Weber, a really good blues bass player and singer who does frontman stuff, which means I can relax and just play my blues thing. So we got together as the Snowy White Blues Project and made an album, In Our Time of Living. The thing is, we didn’t all assemble in the same room together until the day we started recording. We were able to come up with ideas via email. Nobody had even met everybody at the same time. We had a rehearsal in the afternoon, and the next day we went to the studio for about five days and put down everything fresh, mostly live. And I was really pleased, because when you do that you never know what the result will be. It could’ve been a disaster and cost a lot of money—and I was paying for everything. But it went really well and I was very pleased with it, so we decided to go and put some gigs together and get out on the road, which you can hear on In Our Time… Live—a title we chose just to keep the name alive while I’m out with Roger. By the end of this Wall tour, I should be looking forward to going back to some small clubs and playing some blues.

How much songwriting did you do for these projects, and what’s your writing process like?

I write nearly all the songs on the White Flames albums. But with the blues project, we’ve got a few songs each and a few covers. It’s good, because everybody gets his thing in and that’s the best way to do it, really. I’m happy to take a backseat just playing my blues. As for the process, I sit down with my guitar and I strum a few chords to get some sort of direction. If I’m in a mood, I’ll play a minor thing and I might start thinking about what it would be like to play a guitar solo over those minors. And then I come up with a lyric or hook line, and over a period of weeks or months or even years, I just kick it around and put it together. Some songs come really quickly. I had a hit single around ’84 called “Bird of Paradise” that took me about 15 minutes to write—one of those songs that just came out complete with lyrics and everything. And others kick around for ages and eventually something makes it work or not. So there’s no real technique to it for me, no plan—it just comes or it doesn’t.

Is there any new music that inspires you?

I don’t actually listen to music at home. I play it in my car. Occasionally, I’ll hear something I really like. But most of the time I don’t know who it is. People will ask me, “What do you think about this guitarist and that guitarist?”— new young guys—and I listen and say, “That’s great.” But then I forget who they are. And I can hear that a young player’s been listening to Albert King, for instance, and then I remember my old days and think, I know just how he feels—he’s all excited that he’s discovered Albert King. Honestly, though, I’d prefer to listen to Albert King. But I wish all these guys a lot of luck, because they’re some great players and they’re helping keep the blues alive.

Snowy White’s Wall Tour Gearbox

Guitars

1957 Gibson goldtop Les Paul, Gibson goldtop Les Paul reissue with Stetsbar tremolo, 1957 Gibson Les Paul Historic, Gibson ES-345, Fender David Gilmour Signature Series Stratocaster, Fender Stratocaster

Amps

Two Vox AC30s (one is set with extra treble for solos)

Effects

Line 6 M9 Stompbox Modeler, Boss BD-2 Blues Driver, Boss OD-3 OverDrive, Boss RT-20 Rotary Ensemble, Ernie Ball volume pedal, Vox V845 wah

Strings and Picks

.010–.052 sets for Les Pauls, .010–.046 sets for Stratocasters, custom “Snowy White” teardrop-shaped picks

Miscellaneous

Boss TU-2 chromatic tuner, Korg Pitchblack chromatic tuner, Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2 Plus

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)