Taylor Swift never thrashed around her living room or lip-sync’d to one of your songs. But you’re not the Darkness.

“I didn’t think we could get any sexier,” guitarist and lead vocalist Justin Hawkins told Billboard in response to Swift’s 2016 ad for Apple in which she rocks out to the band’s “I Believe in a Thing Called Love.” “But somehow,” Hawkins continued, “Taylor raised the bar.”

The Darkness—the lamé-suit-wearing, falsetto-singing, glam rockers from Lowestoft, England—embody rock ’n’ roll’s glorious, flamboyant id. They preen, cavort, and swan (if that’s even a word) with the best. “I would like to play less because I do enjoy the swanning,” Hawkins says, justifying his role as the band’s solos-only guitarist. “I enjoy a good swan.”

Justin Hawkins, along with Dan, his brother, are the Darkness’ guitarists. Justin takes solos and Dan does most of the heavy lifting. Together they pump out hook-driven, anthemic, head-banging music. Their songs, like their outfits, are attention grabbing, infectious, and fun. They are everything hard rock—especially their type of hard rock, which sits at the intersection of mid-’70s glam and late-’80s hair metal—is supposed to be.

Of course Taylor Swift gyrates around her house to their music. Who wouldn’t?

But spectacle and bravado aside, the Hawkins brothers are also serious craftsmen. Sure, they’re funny, but humor’s just their functional MO. Talk tone, songwriting, or gear—or any aspect intrinsic to music making—and they’re informed, experienced, and opinionated. Those qualities, in addition to being world-class showmen, go a long way in explaining their consistency and success.

Dan is the band’s tonal authority. He plays Les Paul Standards and his pickups are hot. “I just want it to be loud,” he says. “That’s the thing: It needs to bark and sound a bit shit for it to sound like me.” He has similar taste in amps. “I am running an absolutely stock, factory spec, 1959 Super Lead,” he says. “At any time, I have one Super Lead running two cabs loaded with Greenbacks.”

Justin also plays a Les Paul, although his is a Custom. “When I put on a Les Paul Custom, it feels like I am slipping into a warm bath full of my own saliva,” he says. “It couldn’t be more familiar.”

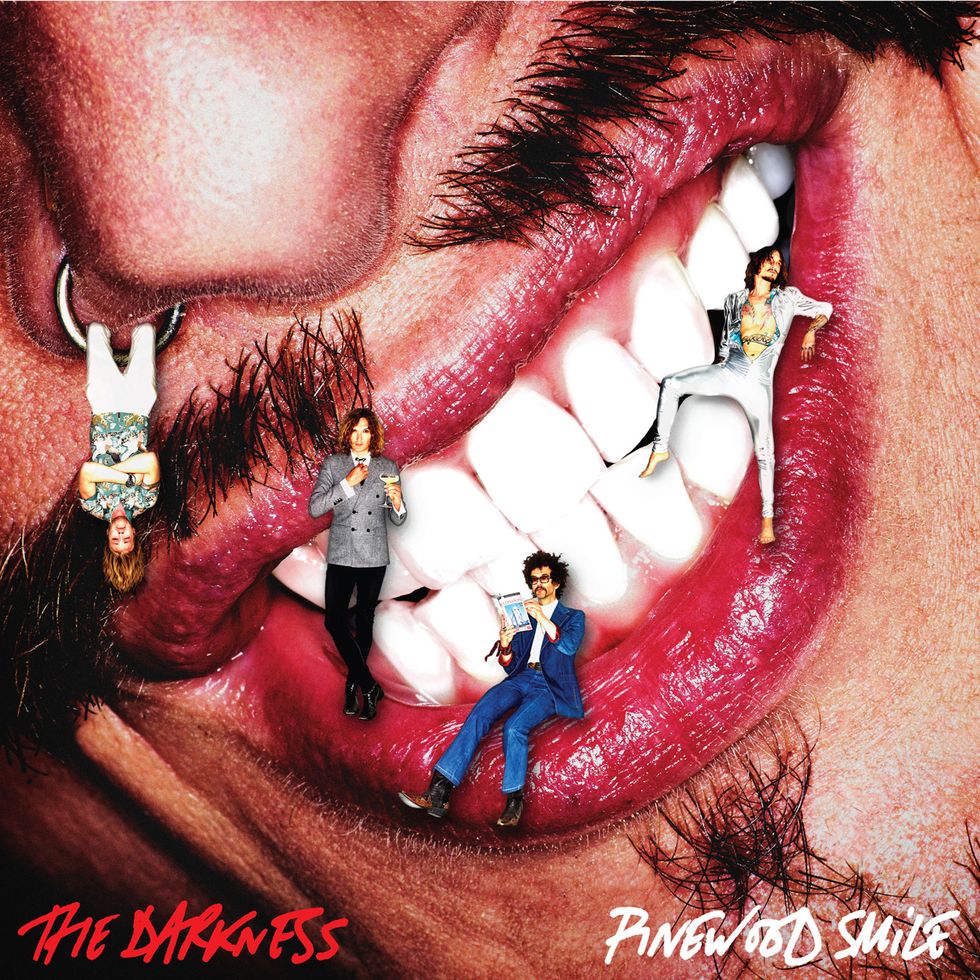

Pinewood Smile, the band’s fifth release and their third since reforming in 2011, came out in October. It’s what you’d expect: great hooks, shout-along choruses, tight playing, and ripping guitar solos. It’s also accompanied by the usual, over-the-top videos, although nothing as outrageous or disturbing as the space-aliens-meet-A-Clockwork-Orange imagery of their official video for “I Believe in a Thing Called Love.”

We caught up with Justin and Dan while they were in Europe on tour in support of Pinewood Smile. We talked about songwriting, acoustics, pedals, and how they distinguish their guitar tones. We also discussed the art of choosing the best key when crafting ass-kicking choruses. Plus, Justin explained his various picking techniques and Dan told us how he makes his Les Pauls even heavier.

When did you first start playing?

Justin: I was inspired to play, initially, by Brian May. I really loved his tone and vibrato and everything. I thought his playing sounded like a singing voice. I wanted to be able to do that. Whenever I went to guitar lessons, I was always asking to learn Queen stuff. I was encouraged, because my brother was playing drums, as well. I felt like we could possibly be in a band together. My parents were really supportive of that, because they wanted us to be like the Jackson ... 2 [laughs]. My father is a hard-working builder. I think he wanted us to have the opportunity to do whatever we wanted. When we expressed a little bit of interest in music, he was really behind it and made it an easy decision.

TIDBIT: Justin Hawkins cut all his guitar tracks for Pinewood Smile while perched in the control room. The rest of the band recorded its tracks together, on the floor.

Dan: I started on drums when I was 8 and I played straight up until I was about 14. At around age 12 or 13, Justin was in a band and they needed a bass player. I said I’d help them out, having not played much bass at all. We did a lot of Marillion covers, Bruce Springsteen, Genesis—a bit prog-y. I moved to London when I was 17 as a bass player for a couple of bands. When I was 24, I think, I was in a band and the singer realized I was a better guitarist than the guitarists. He sacked the guitarists—both of them—and I got moved onto guitar. I never really thought about being a guitarist, which is why I’ve got such terrible technique.

When did you start taking guitar seriously?

Dan: Sad to say, that hasn’t actually happened yet [laughs]. I learned enough guitar to work out how songs were written. I learned everything on acoustic—and a pretty shit one, really. My strings are a slightly lighter gauge now, but when I started playing [electric] guitar I was playing on .011–.056 gauge strings—sometimes it was .012—and with wound G strings, because I’d only ever played on acoustic. I went straight onto electric and it just felt like it was going to fall apart. I was breaking strings left, right, and center, so I put the closest thing to my acoustic strings on and that’s how I started.

Did drumming inform your guitar playing?

Dan: One hundred percent. I think the best rhythm guitar players must have been drummers or are able to play drums. I know I am not much of a lead guitarist. I don’t have the technique and I have no idea what I am doing. If I ever play a solo, I’ve worked it out. I am trying to play a tune; I am not ad-libbing. I focus very hard on getting the rhythm right.

Dan Hawkins may be the only guitarist who’s ever had weight added to a Les Paul Standard. He had lead fishing sinkers placed in a new LP’s chambers, then christened the guitar “the Cod Father.” Photo by Jordi Vidal

How do you divvy up the guitar duties? It’s not just rhythm and lead.

Justin: I always used to try to encourage Dan to play more, because when I hear his solos, I always think, “Fuck, I would never think to do that.” Sometimes he wanders off into the wrong key and it works for him. He plays everything with such confidence that he owns those notes. I don’t do that. I try to craft something that belongs there. I want him to do more so I can prance around, carry a microphone, and not feel restricted by the guitar. But then when I hear a riff that I really love, I sort of fight for it and try to own it [laughs]. We used to jam stuff out, and then whoever is owning it takes it. But I would like to play less because I do enjoy the swanning.

Dan: Basically, I’ll come in with a load of riffs and song ideas. I write them up with Rufus [Tiger Taylor, drummer], and when we get to the point that there is a song there—a structure: intro, verse, bridge, chorus—it is normally after we’ve finished the song that we revisit the solo section. The solos are normally keyed off the song—the emotion of the song and the melody. It is best that they come last, so you can express something that’s got something to do with the song. Normally, I think of Justin like Prince. He sings and plays the main solos. I don’t really like to interfere with that dynamic. I am happy to just sit in the back. But sometimes we’ll have discussions and I’ll say, “I really fancy this key or something,” and then I’ll play something. It is a laborious task.

Do you play rhythm parts, too, or just lead?

Justin: Sometimes I play rhythm parts if I’ve got a guitar in my hands and I can pull it off. But my rhythm playing really suffers when I am trying to sing at the same time. Most of the time, I just play a solo and then give my guitar back to my tech. On the record as well, I hardly play any rhythm—if at all. For about three albums, I haven’t played any rhythm. I am doing lead on records.

Are the lead harmonies the two of you together, or overdubs?

Justin: You can easily tell. If the vibrato syncs up perfectly, then it is me and me or Dan and Dan. If it is a bit of a mess, then it is both of us. Generally, he does the overdub in the studio, and live, we try to figure it out between us.

You both play Les Pauls. What do you do to distinguish your tones?

Dan: The big difference is, I play Standards and Justin plays Customs. That’s the primary thing. He plays with a hard plectrum and he strikes near the neck, and I play with a soft one and bash it right near the bridge. Basically, mine is barking. My sound barks and his sound is a bit more luxurious. If you look at the EQ, I am on happy face and he is … happy face [laughs]. We are the same on many levels.

Guitars

Gibson Les Paul Standards

Gibson J-200

Amps

1959 Marshall Super Leads

Marshall power amp

Marshall 4x12 cabs with 25-watt Celestion Greenbacks

Effects

Mike Hill channel switcher

Diezel VH4 Distortion Pedal

Ibanez TS9 Tube Screamer

Ibanez TS808 Tube Screamer (vintage, with 1458 chips)

Mad Professor Deep Blue delay

Devi Ever Shoe Gazer

Wampler Faux Tape Echo

Strings and Picks

Rotosound Roto Greys (.011-.054)

Dunlop Nylon .73 mm

So, really it’s in your fingers.

Dan: Yeah, basically. And how we’ve got the amps dialed as well. He likes it wider sounding and I’ve got pretty much no presence, middle on full—mine is just honking away. I don’t know why I like that. Every time I try a fancy new amp, or a new setup, or something expensive or boutique, it always sounds good on its own or at low volumes, but as soon as the band fires up, I am like, “Where the fuck are my barking dogs?”

Do you use alternate tunings?

Justin: I only ever play standard. One exception is [Pinewood Smile’s] “Japanese Prisoner of Love,” which has a drop to D on the fat string. I have a capo on the second fret when we play “Buccaneers of Hispaniola.” Beyond that, it is all very standard. I don’t think I would be able to pull off singing and instinctively finding chords. I am not that kind of guy. My brother is very good at alternative tunings and I wish I was sometimes, but I know that it would confuse me. No matter where I am in a song, I always want to be able to find my way home.

Dan: I do dropped D sometimes. I’ve used—I don’t know what the tuning is called, when you drop both the Es to D … it’s the double D! [Laughs].

Obviously.

Dan: We’ll call it that, shall we? I like the way open C sounds with that top string ringing out. I’ve done some interesting stuff in the past, but generally I try to keep it pretty straight. I’ll normally only drop the D if we’ve changed the key of the song and it doesn’t sound heavy enough—like, the root of the song is D where it used to be E. I drop the D and play it low to give it some oomph. I very rarely start off in dropped D. It almost always starts off in standard tuning when I am writing. We talk about the key a lot.

Why? To make it work better with the vocal range?

Dan: Yeah, or we try to get it to where the chorus is kicking ass. For example, we’ll write in E and then Justin will write the melodies and lyrics. He’ll start singing it and we’ll go, “It’s kicking ass in the verse, but the choruses drop.” Sometimes we keep moving the key until it makes sense. But then I have to completely relearn it.

Is that why you use a capo sometimes?

Dan: Yeah, that’s the only reason I use a capo. I very rarely reach for a capo and say, “Let’s write a song.” Normally, we end up using one out of necessity.

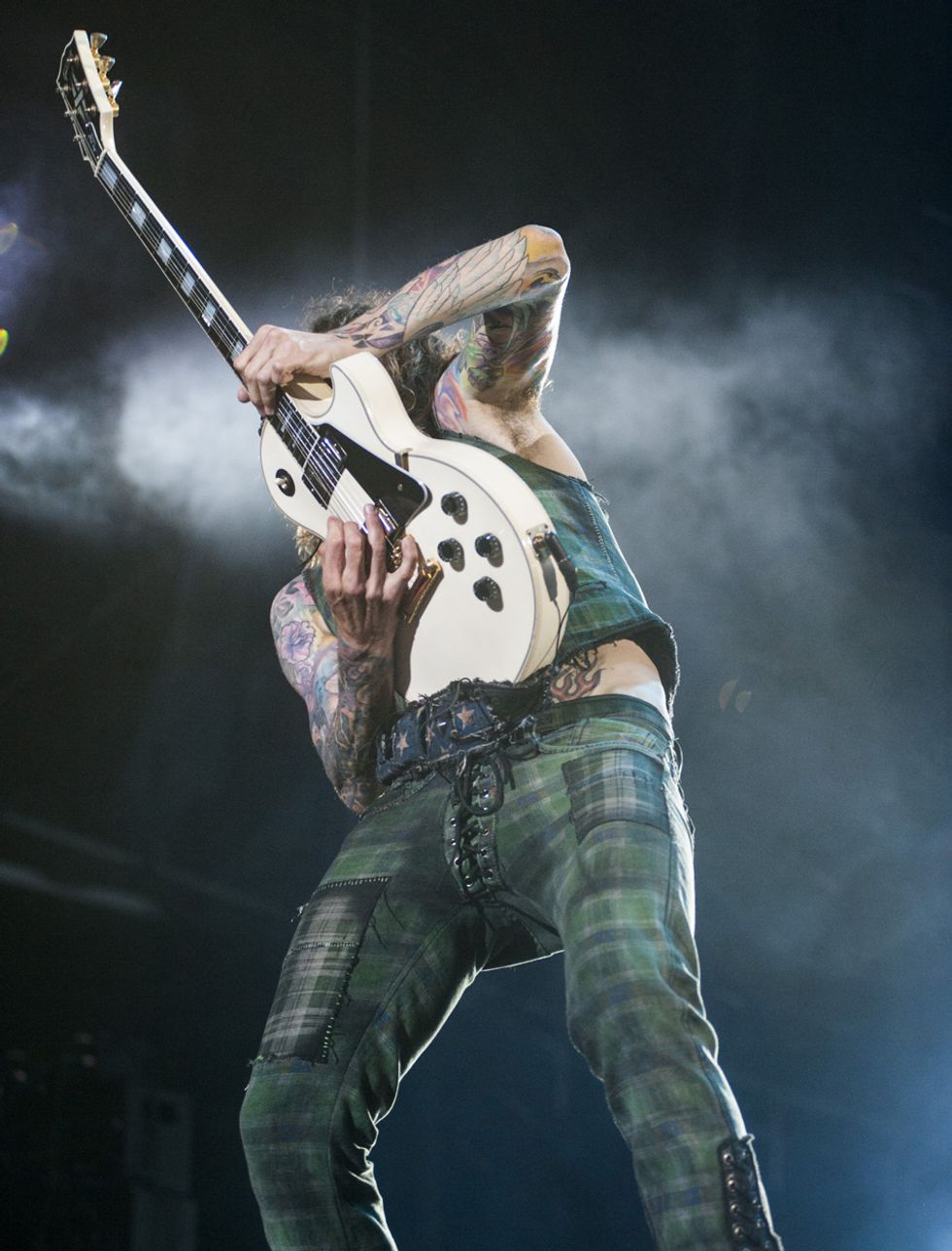

Justin Hawkins goes below the belt for one of his solos. “Most of the time, I just play a solo and then give my guitar back to my tech. On the record as well, I hardly play any rhythm,” he says. Photo by Jordi Vidal

Justin, describe your picking technique. You use a lot of extended and hybrid techniques in addition to alternate picking.

Justin: I started fingerpicking about a month after I stopped lessons. I bumped into my guitar teacher and he noticed it at a show. He was really offended by it. He said, “What happened to your plectrum technique?” I said, “It’s still there.” It is important to have a varied approach. Nine gigs out of 10, I drop the plectrum at an inopportune moment and I have to do fingerpicking. Plus, certain solos are impossible to pull off with my plectrum technique. The hammering stuff, I don’t think I ever really mastered that, but I know a number of ways to do something. My tech is a very brilliant guitar player named Ian Norfolk—he’s like a local legend—and he told me something that really resonated with me. He said, “All that picking stuff—the hammering stuff—is a trick.” It’s like magic. It’s a distraction. And once you know a couple of tricks, that’s all you need, really. I don’t use it all the time because I don’t enjoy listening to it that much, really, but it is quite handy to have if you’ve run out of ideas. You do a trick.

You’re a very melodic player. Your solos stick with the melody and are very singable.

Justin: That comes from being a Brian May enthusiast. For me, they were one of those bands that had two voices: Freddie, and Brian’s fingers. I want to try and do both.

Who plays the acoustic parts on the new album?

Justin: That’s Dan. He’s Mr. Acoustics. I love listening to Dan play. A lot of times he does stuff and I don’t have a clue how he came up with it—what was in his mind or where his fingers went. He reminds me of Jimmy Page. I don’t usually try to learn Jimmy Page things because I prefer having the mystery of not knowing how he achieved those things. I feel the magic would disappear if I tried and realized it was easy [laughs]. I like the illusion.

Dan: I love playing acoustic. As I was saying before, that’s how I learned to play the guitar. I am still working out how the electric thing goes, but I love playing rhythm guitar. I can’t tell you how much I love playing rhythm guitar. Hitting it hard, strumming—it’s just my thing. Maybe I miss being a drummer.

even louder." —Justin Hawkins

What acoustics do you have?

Dan: I have a Gibson J-200. I got it in 2003. It might be a 2000 model. It was actually a gift from my publisher when we signed to Universal. Just before we signed, he brought down these guitars. I got a J-200 and Justin and Frankie [Poullain, bass] got Gibson Songwriters. For years, I kind of preferred that to my J-200. I can’t really explain it, but now it is almost 18 years old and it seems to have dried out, become lighter, and just sounds better. That is quite good news for people who have bought Gibsons maybe 15 years ago. I can tell you now, they do sound better the older they get. Still. It’s not just the old ones that sound good. Because of what they’re made of, the fairly modern ones sound better the older they get, too. But that’s just my experience. I might be talking out my ass.

Do you take the acoustics on the road?

Dan: We used to. Increasingly, we seem to be streamlining what we do and getting it completely undiluted. I think people want to come and see us because we fucking rock. We’re doing this old school, glam rock, exciting party thing. I don’t think people want to see us experimenting, fucking about, and playing ballads. We are gradually sort of ditching everything. We’ve had keys in the past, and acoustics and mandolins, but they all just get thrown in the sea at the end of the tour and we get back to doing the hard rock stuff.

Do you use pedals?

Justin: No. I just have two amps. One of them is loud and one of them is even louder. I have a Marshall Jubilee in the rig at the moment. I am not sure what that is doing exactly. My rhythm sound is a Friedman, which I use a lot for solos in the studio as well. It just works for the way I play for some reason. My lead head is a Wizard 100. I just have a Mike Hill channel switcher, a Sennheiser wireless system, and I give the guitar to my tech, Ian, and he tunes it for me. The rest of it is fingers.

Guitars

Gibson Les Paul Customs

Amps

Wizard Modern Classic II (100 watts)

Friedman Small Box (50 watts)

Marshall Silver Jubilee

Marshall 4x12 cabs with Celestion Vintage 30s

Effects

Mike Hill channel switcher

Strings and Picks

Rotosound Roto Yellows (.010-.046)

Dunlop Tortex .73 mm

Sennheiser wireless

What’s that effect on “Lay Down with Me, Barbara,” on the new album?

Dan: There is a phaser. I think that’s an MXR Phase 90. That was my idea, but just because that is what the song needed—really ’70s. I wanted to keep that vibe going. He won’t use one live. He hates all that shit. About the only thing from his setup that’s fairly complicated is the wireless system.

Do you use a wireless as well?

Dan: No. No, no, no. Fuck that. I have no interest in being wireless. I tried one once and I spent the whole time trying to recreate the sound of a cable. I thought, “You know what? If this means that I can’t run around stage so much, so be it.” I need to present a nice big fat guitar sound, not fucking run around like a twat. I’ll leave that to the people who have to run around. I am a big fan of the lead [cable]. I think it makes things more interesting as well, when you go wandering and you don’t know where you are going to get stuck. I’ve got stuck so many times wrapped around the pedalboard and one of the monitors. You go to the front of the stage and you can’t actually get back. It gets very Spinal Tap sometimes. I think it is worth it.

In the studio, are the rhythm tracks done together as a band and then you overdub vocals and solos?

Justin: The band is in there together when that’s happening. Sometimes I go in there with them and help with arrangement cues and things like that. But I am not recording anything when the band is doing that. It’s rhythm guitar, bass, drums, and I am prancing around trying to help.

When you record your parts, do you sit in the room with your amps or in the control room?

Justin: I have had occasion to do both. On the last one, I was in the control room, but there are lots of times when I am in with the amps. When I am on a roll, I just stick where I am and with whatever is working.

Dan, I read that you like your Les Pauls heavy. Why is that?

Dan: I’ve got an interesting story about that, actually. Gibson sent me one of these new Standards, which sounds really good, but I did have it modified. I had the pickups I use—498s, I think—put into this. It was still great, but it just didn’t feel right. And I didn’t like the way it looked either, so I had it refinished by Guyton Guitars, the guy who does Brian May’s stuff. He’s looking after our guitars these days. I said, “Can you fill these chambers?” They chamber their guitars now and I fucking hate it. It feels like it is going to fall apart. I sent it out and said, “Make it heavy again.” What he did was he put a load of fishing weights in there. We named the guitar the “Cod Father” in respect to that. True story. That guitar is now as heavy as my normal ones and it’s got a load of lead in it.

So it really is a heavy metal guitar.

Dan: Quite literally, yeah [laughs].

Watch the Darkness perform "I Believe in a Thing Called Love" live in 2017. Lots of Les Paul action in this clip, including a bluesy extended intro by Justin Hawkins, who also navigates a smooth guitar swap after breaking a string on his Custom.

Dig even deeper into the Hawkins' brothers gear and bassist Frankie Poullain's setup, too.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)