Few contemporary bands have reached the level of commercial success that the Dead Weather repeatedly achieves with its simple, potent equation: anarchy + chaos + melody = rock ’n’ roll. As the Nashville-based quartet featuring Jack White on drums has progressed from its 2009 debut, Horehound, to 2010’s Sea of Cowards (both of which debuted in Billboard’s top 10) and now to this year’s Dodge and Burn, they’ve amped up that math to create the sonic equivalent of a human cannonball. Songs like “I Feel Love (Every Million Miles)” and “Cop and Go” fly out of the speakers—arms and legs of octave-fattened guitars, buck-wild keyboards, fuzztone bass, and expressionistic power drumming poking out in all directions—then somehow tuck into a neat landing via Alison Mosshart’s seductively ferocious vocals.

At the center of the aural cyclone, usually seen manhandling a big-boned Gretsch White Falcon in his job as melodist, riff master, and sonic insurgent, is Dean Fertita—who can also be seen filling those roles in various balances with Queens of the Stone Age, the Raconteurs (White’s other other project), and in his own smart-pop project Hello=Fire. Fertita knows guitars and keyboards like John Henry knew hammers and spikes, and he can—and does—drive them to places that are both unpredictable and a reflection of the Big Rock Handbook, which must be where he got the Jimmy Page tone on Dodge and Burn’s ripping “Let Me Through.”

Although he’s lived in Nashville, the eye of White’s ever-expanding Third Man Records hurricane, for three years, Fertita hails from Detroit, home to one of America’s original sonic-anarchist outfits, MC5. And while Fertita’s doesn’t incorporate the twisted jazz elements that MC5 guitarist Wayne Kramer did as he and his ’60s proto-punk bandmates patrolled the badlands between Chuck Berry, Sun Ra, Dick Dale, and John Coltrane, the same untamed spirit is in his playing.

Piano was Fertita’s first instrument. “From ages six through 12, I studied classical piano, and then the ragtime, Scott Joplin thing,” he says. “But I got a guitar and an AC/DC record when I was 13 and it was ‘game over.’ Studying became all about playing guitar and learning from listening to records.” Motor City radio fed him a steady diet of classic rock, and then in the ’80s punk rock slam-danced into the picture. The ’60s figure into the equation, too: Part of Dodge and Burn’s sound is dipped from the reliquary of epic rock mixing. The wild panning, lustrous textures, and bold separation of tracks flash back to late in that decade, when artists like Hendrix, Pink Floyd, and Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac were inventing the bumper-car trickery of the headphone mix.

Eyeballing Fertita’s current resume—and the multi-band antics of White, Mosshart (who also fronts spiky rockers the Kills), and bassist Jack Lawrence (of the Raconteurs, garage rockers the Greenhornes, etc.)—it’s obvious why it took five years to make Dodge and Burn. But along the way subscribers to Third Man Records’ Vault program got sneak peaks at four of the album’s dozen songs.

“Open Up (That’s Enough),” with its spanking guitar chords, and the psychedelic potboiler “Rough Detective” were released as a teaser 7" single in 2013. The next year, “It’s Just Too Bad” and the Fertita-fueled riff machine “Buzzkill(er)” followed. Nonetheless. Dodge and Burn is cohesive as an atom—even though, as Fertita explains, it was chiseled from a fat slab of choices, sometimes starting with his own multi-instrumentalist impulses.

Playing in so many stylistically different bands—Queens of the Stone Age, Raconteurs, Dead Weather, Hello=Fire—must be a kid-in-a-candy-store experience.

It is. I can explore every part of my musical personality. What’s great is there’s no pressure in any one band to try something that might not be appropriate just because I’m interested in it. There’s a place for every sound and idea.

The Dead Weather's arsenal of Gretsch guitars and basses. Angelina Castilla for Third Man Records

The bands do seem to have a similar unpredictability and devil-may-care attitude. Are there other similarities?

Because of how these bands operate, you don’t really bring in finished songs. For example, there were two songs on Dodge and Burn that I’d tracked the guitar ideas for—although when I recorded the ideas I didn’t have any specific songs in mind. They were parts I figured I’d use at some point, and they ended up in “Buzzkill(er)” and “Too Bad.” In “Buzzkill(er),” the main guitar riff sound is an Electro-Harmonix POG and the Fulltone Tube Tape Echo. But with all these situations, it’s more about discovering something new or thinking about your instrument in a new way. It’s not so much that I develop a stockpile of riffs and stuff. It’s more developing gut instincts and ideas.

In the Dead Weather, you’re a lead guitarist in a band that has a terrific lead guitarist behind the drum kit. Does Jack White ever voice opinions on your playing?

I have free rein but of course, if he has suggestions, it’s an easy relationship that way. I might want to go on and on doing takes, but having another guitar player there to say “That was the cool one” makes my job a lot easier. But he never suggests what I play or insists on anything. He enjoys playing a different role in this band.

How would you define your role?

It’s difficult to pin down, but I feel like what I do is in direct connection to Jack Lawrence on bass. It’s important that the guitar and bass feel connected at all times. The [Electro-Harmonix Bass] MicroSynth-driven sound he plays is part of the defining sound of Dead Weather, so for me the guitar and bass become one big thing together. If Jack records a song with that sound on it, it will drive me to find another way to complete the space. I never really know what that is until I play it. It could be a clean part that cuts through Jack’s bass part, or maybe the same part he’s playing but with some fuzz—which we did for my riff on “I Feel Love”—or maybe some kind of counterpoint. On “Let Me Through” I felt the guitar needed to be an extension of his tone but still be distinctive. To emphasize the lyrics, the guitar needed to bust through, too. So I used the Bit Commander pedal, which gave a percussive, synth-like feel to the guitar.

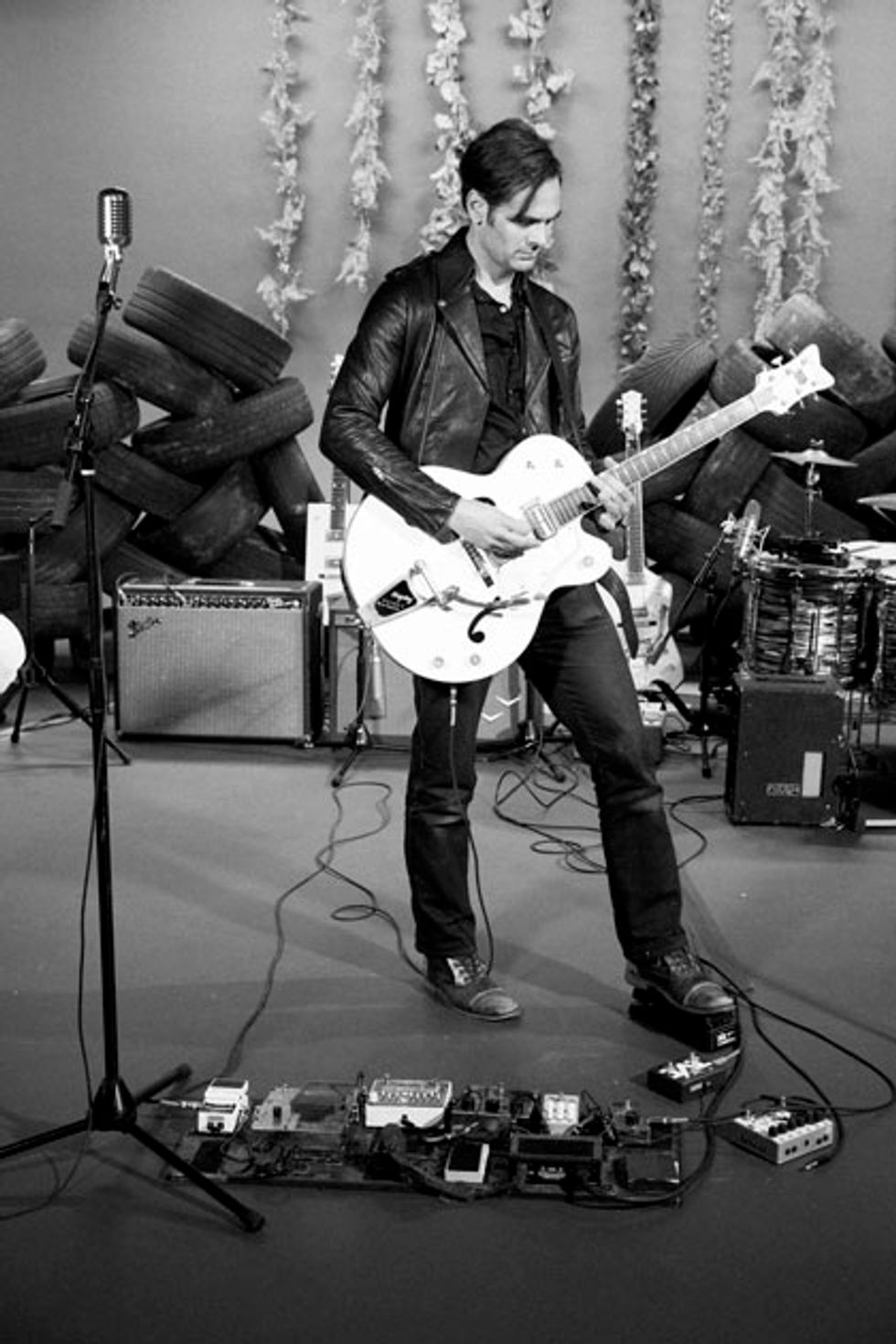

Armed with Gretsch White Falcon, guitarist Dean Fertita rips away at Third Man Records HQ in Nashville. Photo by David James Swanson

Do you typically approach the songwriting process in terms of sounds, or as notes, chords, and scales?

I lean more toward sounds. That’s probably the result of all the things I listened to growing up, and taking lessons and finding where my real interests were. I took theory classes when I was younger, and I liked learning about the way things relate to each other musically, but it wasn’t exciting. I never found myself thinking that way when it came to being in a room with people and writing music. It’s more instinctual, primitive, for me. I like to feel music more than think about it.

Which of your early musical interests would you say fueled your interest in sounds over academics? Were you into Detroit bands like the MC5 or Iggy Pop, or textural jazz like John Coltrane or Sun Ra?

No, I didn’t listen to any of that stuff. I didn’t even discover Iggy and the Stooges or the MC5 until much later, when I was already playing and recording in bands. It was pretty much whatever was on the radio, and growing up in the ’70 and ’80s in Detroit, all we had for radio was classic rock. I loved AC/DC, Led Zeppelin, and Black Sabbath. I wanted to be Jimmy Page for a while, until I realized that was impossible [laughs]. And there was some hair metal. Eventually punk rock come along and I heard the Dead Kennedys and the Sex Pistols.

Do you record riffs on your own or spend time in the studio working on new guitar sounds to create a bank of ideas you can draw from?

I really don’t. I should, I think, but maybe I’m too lazy or just need that push of being in a recording situation. I did record the riff for “Buzzkill(er)” when I was in a studio one day—just by luck I came up with it and figured it would come in handy at some point. If I come up with an idea while I’m sitting around at home, I might record it on my iPhone, but I prefer to create sounds by reacting. In the Dead Weather, everything is very spontaneous: Whatever I play depends on what’s in the room. I like to hear where the song seems to be going and then I might plug my guitar into a certain amp, grab a few pedals, and dial up a sound to see if it fits. If it doesn’t, I’ll tweak it or try to find another sound. Or I might walk up to the keyboard. It kind of depends on what’s available and what other people are already doing. For me, being flexible keeps things exciting and creative, and everybody in the Dead Weather is into that kind of spontaneity.

Let’s talk about some specific songs on Dodge and Burn. “I Feel Love (Every Million Miles)” has this turbulent wall of sound that parts like the Dead Sea and then rolls back in again. How did you create those huge, roiling guitar sounds?

The intro riff features a Moog analog delay. I just plugged into it and started playing that riff, and it became the foundation for the song. It’s also double-tracked. We played the song through three or four times, and then decided we wanted more clarity in the verses and choruses than the intro and the bridge riff—there was too much delay. So for the verses and choruses, we plugged my Tele into a combination of Selmer and Magnatone amps, with a Fulltone Tube Tape Echo—which I use mostly for the gain stage. In the verses, I leaned heavier on the Selmer and might’ve used an MXR Micro Amp as a preamp. The bridge was mainly my reissue Magnatone with the delay.

Dean Fertita’s Gear

Guitars

Fender Telecaster

Gretsch White Falcon

Amps

Magnatone

Fender Twin-Reverb

Selmer

No-name “magnetic” amp

Effects

EarthQuaker Devices Bit Commander

Fulltone Tube Tape Echo

Moog MF-104M Analog Delay

Electro-Harmonix POG

MXR Micro Amp

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Regular Slinky strings (.010–.046)

Fender medium picks

Jack Lawrence's Gear

Basses

Gretsch White Falcon

1964 Fender Jazz

1966 Fender Precision

Vintage Hofner 500/2 Club

Amps

1965 Fender Bassman

Ampeg B-18

Effects

Electro-Harmonix Bass MicroSynth

ProCo Rat

Custom DI box

Strings and Picks

LaBella Deep Talkin’ flatwound strings (.049–.109)

Fender heavy picks

Speaking of the Magnatone, what drew you to it?

I have a reissue that I’m also using with Queens. It’s about character with me—finding things that just twist your ear and your way of thinking a little. To hear the same things you’ve been playing forever differently is, again, key for me. I like the response the low strings have on the Magnatone, especially at lower volume. I’ve also recently been playing a Watkins Dominator II. That’s also one those amps that, wherever you set it, it sounds great and full.

“Rough Detective” has a lot of radical separation and panning in the mix. How do you decide which songs get the psychedelic treatment?

We did the album with the idea that we were going to make singles. When people used to make albums, they were a compilation of singles. We cut songs two at a time for the first eight we did.

Mixing was about finding the strategy that complimented the other song. “Rough Detective” lent itself to getting a little psychotic with the mix.

Besides the POG and Fulltone, do you have a palette of go-to effects?

There were just a couple of effects that were used a ton on Dodge and Burn. The EarthQuaker Devices Bit Commander, which is an octave pedal, saw a lot of light for these sessions. And the Fulltone Tube Tape Echo. They make guitars sound big.

What do you look for in a guitar?

A new way of looking at doing the same thing. You learn the basics of guitar in a couple weeks and spend the rest of your life refining how you

interpret those ideas.I recently got a Goya guitar, which is a 1960s Italian brand. It’s not the easiest to play. I can’t really take it on tour. It’s hard to control the sound in a live environment. But I love that guitar, and it makes me play a little differently than my Tele or the Echo Park guitars I’ve been playing with Queens.

Tell us more about this Goya.

I used it in place of playing an acoustic. It’s a hollowbody, so it was nice for playing at home and not having to plug into an amp. But the tone sounded very electric, even while playing it acoustically. That’s what drew me to it. I could visualize how stuff was going to sound through the Magnatone. Every guitar has a personality of its own, and having a different sensation in my fingers makes me play differently. I don’t have a “type.” I go for something that makes me feel something that day.

YouTube It

Dean Fertita’s slippery, corpulent riffs set the mayhemic mood while Jack Lawrence’s rumbling bass and Jack White’s brutal drumming provide a bombastic backdrop for Alison Mosshart’s sultry howls on this live take of the new Dead Weather single, “I Feel Love (Every Million Miles),” on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.

Bassist Jack Lawrence boogies down while frontman Alison Mosshart has a blast. Photo by Lindsey Best

Jack Lawrence on His Quest for New Bass Tonalities

“When we were recording Dodge and Burn, I was trying to learn to work more with feedback in the studio,” explains Dead Weather bassist Jack Lawrence. “I was experimenting with using hollowbody basses and getting closer to the amps. Getting up there and pulling back, getting up there and pulling back—like, bobbing back and forth, trying to get the right spacing between the pickups and the speakers.”

Lawrence jokes that this approach “probably looked silly from the control booth”—but the results sound thorny and authoritative—all fuzz, fury, and, at times, even funk. The charter member of the Dead Weather and Raconteurs explains that he’s been on a quest for different tones over the past few years, and that’s reflected in the gut-punch of his performance on Dodge and Burn’s dozen tracks.

“I usually use flatwound strings,” he says. “I’m allergic to nickel, which means I can’t use nickel-plated roundwounds. With flatwounds you get a little dumpier sound. But I wanted a little more aggressive sound in general this time—a sound you could get with roundwounds. So in the studio I cranked the treble up and used smaller speakers and cabinets. The [ProCo] Rat pedal was also key for me getting that roundwound sound with flatwounds—like on ‘I Feel Love (Every Million Miles).’ The Jesus Lizard were my favorite band growing up, and I use a Rat because David William Sims used one in that band.”

Lawrence affirms Dead Weather guitarist Dean Fertita’s observation that their playing’s intertwined tonalities are a big component of the band’s sound—which is why they focus on each other onstage and in the studio with an intensity usually reserved for bassist-drummer relationships.

“When I use my Electro-Harmonix Bass MicroSynth pedal, Dean and I have to work together as a unit instead of the traditional drums locking in with the bass and the guitar playing melodies on top,” Lawrence explains. “That pedal has got a big sound with a sub-octave and square waves. If Dean and I aren’t locked in, those frequencies can eat up the guitar. But if it is balanced, it sounds really amazing.”

The MicroSynth provides the body of the howling Rottweiler tone on “I Feel Love,” as well as “Mile Markers,” but Lawrence also used good old-fashioned amp overdrive, turning an Ampeg combo and an original 1965 Fender Bassman wide open. “The Ampeg has reverb and tremolo,” he relates. “ I didn’t use the tremolo in the studio, but a hint of reverb was nice. And on ‘Cop and Go,’ that’s just using an old hollowbody bass and the Fender Bassman cranking. I didn’t use a fuzz pedal on the record—that’s all just speakers blowing up!”

Lawrence also used a pick more often on Dodge and Burn, and it’s especially prominent in the propulsive bottom of “I Feel Love (Every Million Miles).” “I don’t use a pick that much in the Dead Weather, because not many of our songs have called for it. I like the picky-ness of somebody like [session legend] Carol Kaye, but it’s hard to play in any kind of funk style that way. ‘Three Dollar Hat’ is a good example of me going for a funkier thing. But even if I use my fingers, the pick will be in my hand to switch off mid-song sometimes.

“The tone I get out of the bass amp is also going to guide me,” he adds. “If I turn on a pedal, I’m going to play a different riff than if I was just playing right into the amp. But whatever I do, it’s mostly decided on the spot when we record at Jack’s place. We’re all playing together in one room, and sometimes Alison is the only one not in the room with us—her vocals are usually recorded through an amp in a small booth—so everything bleeds together. There’s a lot of guitar in the drum mikes, so if we like a take we can’t really punch in too much. That’s why this record has a lot of feel to it and everything’s not perfect.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)