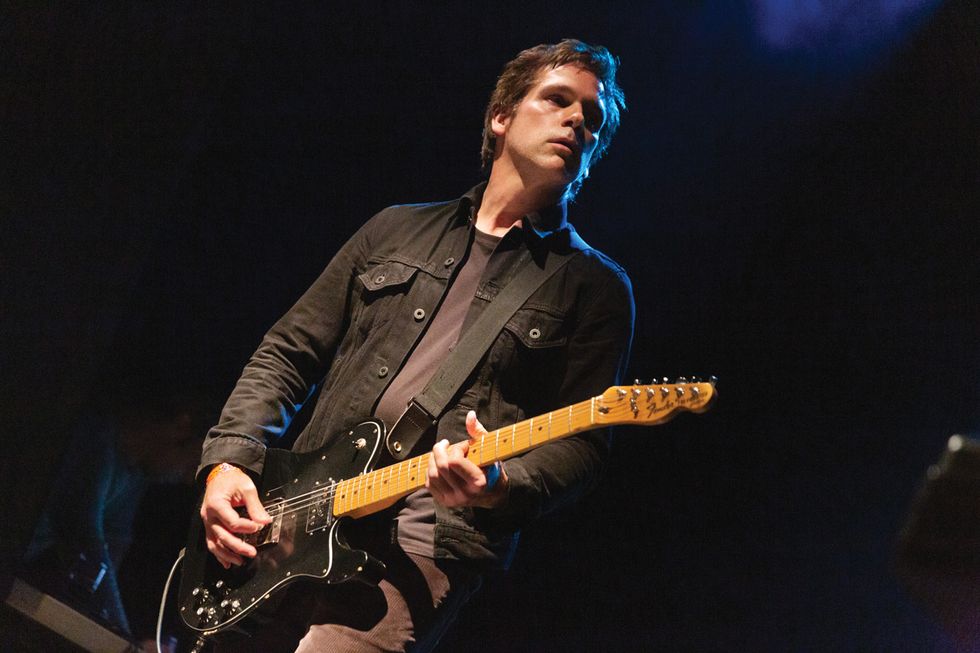

Larry Schemel, from the Los Angeles-based psychedelic band Death Valley Girls, has been on the scene and in and out of bands for over 30 years. He's a seasoned, grizzled professional, and quit his day job ages ago. Yet despite that, he doesn't use vintage or high-end gear, his closets aren't packed with expensive boutique devices, and the pedals he does use aren't even mounted on a board. His No. 1, and basically only, guitar is a Mexico-made '90s-era Telecaster Custom reissue, and his amp—where he gets most of his grit—is a $400 Ampeg GVT 1x12 tube combo. That's it. And no, he's not looking to upgrade.

“If I was in a band with a huge budget for amps, I would just want a bunch of these," Schemel says in reference to his Ampeg GVT. “That's the sound. I'd probably have a bunch of Ampegs on different settings. Over the years, I've gone through so many different things—it's that ongoing quest for your perfect sound, and it is still evolving. But as far as getting the simple tone and sound out of a guitar plugged into an amp, this is it."

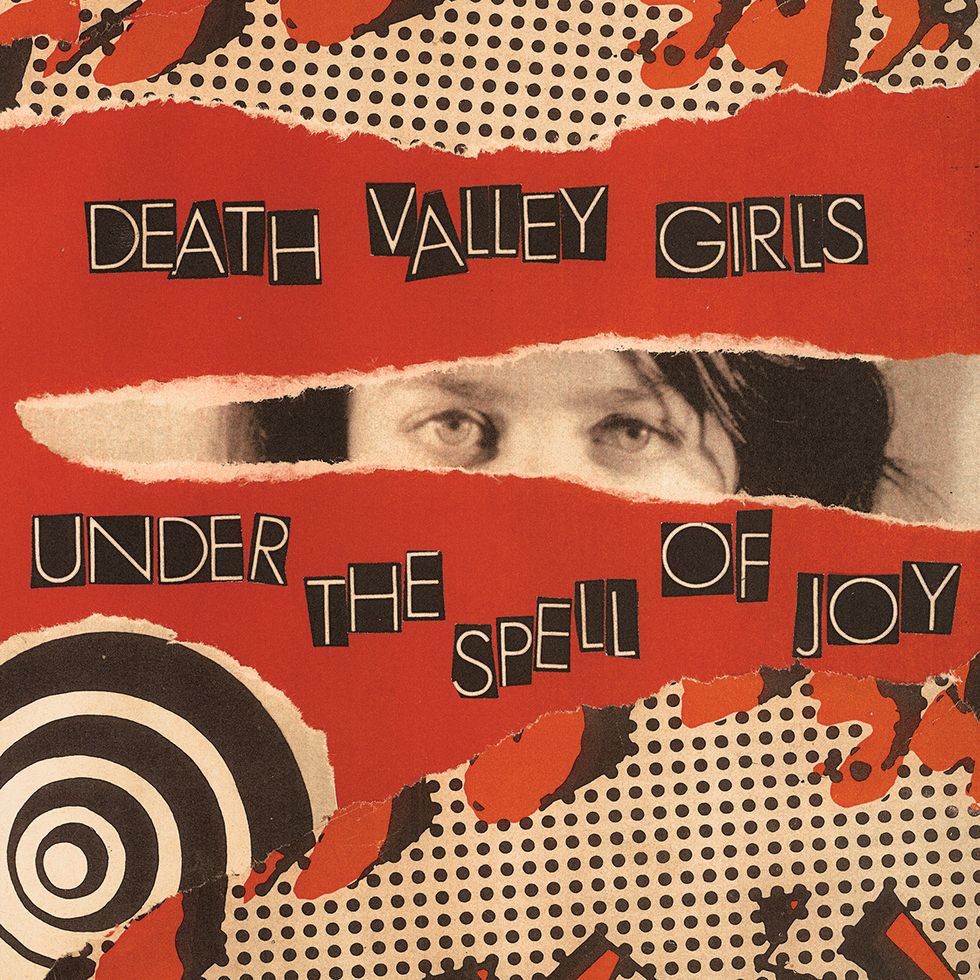

Death Valley Girls started in 2013 when Schemel's sister Patty, of Hole fame, introduced him to multi-instrumentalist Bonnie Bloomgarden, and they discovered they had instant chemistry. Since then, the band has been on the road, back and forth between the U.S. and Europe. They've released four albums, including the recent Under the Spell of Joy. (The album's rhythm section is Rikki Styxx on drums and bassist Pickle, aka Nicole Smith.) And they somehow convinced Iggy Pop to recreate the short film Andy Warhol Eating a Hamburger as the video for their song “Disaster (Is What We're After)," from 2018's Darkness Rains.

Under the Spell of Joy is hypnotic and brooding, and often sits on one riff or alternating two-chord pattern—á lathe Stooges—throughout an entire song. Schemel's playing is understated and textural, although there are breakout moments, like his melodic, vocal-esque leads on “Hold My Hand," or his very Keith Richard's “Bitch"-style solo on “10 Day Miracle Challenge." And speaking of Richards, that brings us back to Schemel's gear, and particularly his Tele Custom reissue and Ampeg GVT.

“It's crazy, because I am a huge Stones fan, but I wasn't familiar with what setup Keith was using in what eras," Schemel says. “That '72 Tele and that Ampeg—that's the Keith Richards setup, and that's my favorite Stones era. That's so cool. It wasn't intentional. It just happened, and I was like, 'This totally makes sense.'"

Serendipitous low-budget gear choices notwithstanding, we spoke with Schemel from his home in Los Angeles to discuss his idiosyncratic ear for equipment, his stint with garage legend Roky Erickson, coming of age in Seattle when grunge ruled the world, the many projects he's been involved with over the years, his unique songwriting sessions with compatriot and bandmate Bloomgarden, and the beauty of minimalist guitar playing.

Tell me about your Tele.

That's my main guitar. It's a mid-'90s Tele Custom, which is the 1972 Fender Tele Custom reissue. It's a Mexico-made Tele with a maple neck, and I got it new. The Custom is always with a humbucker and a single-coil, unlike the Deluxe, which has two humbuckers. I mainly use the single-coil bridge pickup. I'll use the humbucker occasionally live, like if I do cleaner stuff and I want a warmer sound, but for the most part, it's that bridge pickup, because I love that Tele sound, that trebly grit. I am pretty much playing that live full-on.

Even when you're playing with a lot of fuzz, your tone still has that single-coil, bolt-on-neck sound.

I landed on the Tele later. I love Fender stuff, and one of the first guitars that I had—that was a real guitar, other than a crappy budget guitar—was a Fender Jaguar. From there, I used a Les Paul in one band, and I had an SG, but I was drawn toward Fender stuff.

I was once at the Chicago Music Exchange, and there was a guitar there that I'd never seen in real life, which was the Fender Esquire. I was really intrigued by it, because Syd Barrett played an Esquire on that first Pink Floyd album. That guitar sound, to me, was so out there. You could cut glass with it. The guitar at the Chicago Music Exchange was $30,000 or something like that. I played it, and it was one of those moments when you pick up a guitar and play it and it's just magic. It's playing itself. You can play a song immediately and it feels so good. If I had the money, I would have got it right then and there. It's one of those things, and it even happens with the cheaper models, where you think, “This has got the mojo."

Is the period of Pink Floyd when Syd Barrett was in the band one of your big influences?

Oh yeah, that was big. As a teenager, as I grew up from hard rock to punk, and then going backwards to the 1950s and '60s, the psychedelic bands were a big influence. I love all the Pink Floyd records, but the first one, especially with Syd's guitar stuff on there, is really out there. It's psychedelic, but it's also heavy and driving, and his guitar playing was wild. It had a similar quality to the Velvet Underground, which was huge: that unhinged playing and the tones they get. And, of course, the 13th Floor Elevators were huge, too.

After listening to a passel of Ethiopian funk on tour, the band wed that genre's furious grooves to its own psychedelic instincts for the new Under the Spell of Joy.

There's a picture on your Facebook page with you playing with Roky Erickson and Billy Gibbons. How did that come about?

That's not photoshopped [laughs]. Death Valley Girls played a festival in Southern California with a bunch of other bands, and Roky Erickson's band played. After the show—it was an amazing show—me and Bonnie went up to the guitar player and told him “that was amazing." He asked what band we were in. We told him, and he said, “I have your record." We stayed in touch and—fast-forward a year-and-a-half or so—we get an email saying, “Roky Erickson's band is going to tour and we want you to come out with us." We said, “Yes. Totally. Awesome." A couple weeks later, the guitar player, Eli Southard—he was Roky's main guy—messaged me and said, “We need a second guitar player for the band. If that interests you, it would be cool if you could be a part of it." Without hesitation, I was like—oh my god this is insane—“Yes, I'll do that!" Eli sent me the songs. It was 35, half of which were 13th Floor Elevators' songs and half were Roky Erickson solo stuff. I knew all the songs, but there's a difference between listening and knowing a song versus having to play the song. It messes with your mind, because some of the stuff was either way easier than I thought, or way more difficult. Especially the Elevators' stuff, where it's like, “Is that a bridge? Why does that part go seven-and-a-half times and then that other part goes three times?" They were definitely on psychedelics when they wrote that music.

I learned all the stuff. We drove to Austin, Texas, and met up with the band. I got in a couple practices with them, and we were on the road. It was awesome. Roky was super cool, and we ended up doing a couple of tours with them. At the end of one of the tours, we were playing at the Roxy in L.A. Billy Gibbons lives in L.A., and he and Roky are old friends from when Billy was in the Moving Sidewalks. Billy showed up to the show, and someone asked Billy to come onstage and play a song with us. We did “You're Gonna Miss Me" for the encore, and so it was me, Eli, and Billy on guitar, and it was an out of body experience. I was playing this song, which is a classic psychedelic rock song, with Billy Gibbons right next to me. I thought, “This is what it's all about." That was a mind blower. I am just glad there's pictures of it, because I am like, “Did that really happen?"

On tour as part of Roky Erickson's band, Larry Schemel—at stage right—jammed with fellow Erickson guitarist Eli Southard and the one-and-only Billy Gibbons at Los Angeles' Roxy. Gibbons and Erickson, seated, were friends from their early psychedelic rock days in Texas, in the '60s.

Was playing with Roky different from how you normally do things?

I was really flying by the seat of my pants. Eli would write the set list and it was different every night, but what was really crazy was that Roky never had a set list. Roky would know by the riff or how the song would start. He would just know. He lived inside those songs forever. Sometimes he'd go off on a tangent, and we'd just have to follow him. But it was cool.

After going through that, I realized I can't underestimate my own will to step up to the stuff. Even if I am not comfortable, or if my skills are not good enough to pull it off, it's in there. I think it's in all musicians to just do it. Don't worry about it. Even messing up … that's even going to happen in my own band. That's inherently part of playing music. It's unpredictable, and there are always those weird nights where you think you had a really bad show, and someone comes up to you and says, “That was so amazing, especially that one solo you did." I am like, “What?" I think a lot of us are hard on ourselves. You mess up two notes and you're like, “Damn it." But if the feeling and passion is there, it doesn't matter. It's okay if you mess up. It doesn't have to be technically precise as long as the feeling is in there.

You've been on the scene for a while. What's your backstory and how did Death Valley Girls come about?

I live in L.A. now, but I am originally from Seattle. I grew up in that whole scene up there, with the grunge bands and everything. When I first started playing guitar as a teenager, I got a little later start than some of my buddies. My friends started playing when they were 12 or 13, and by the time we were 15, I'd go to my buddy's house and he'd be like, “Hey, you want to hear 'Eruption?'" I thought, “I can't do that." Those guys were so beyond, it was nuts.

But my sister, Patty, is a drummer, and she started playing early. She was getting really good. Our dad bought her a Pearl drum set, and she started playing in the garage. When Christmas rolled around, she got me an electric guitar and an amp. It was one of these budget, weird off-brand guitars, and a little amp, and I started teaching myself how to play with the Mel Bay books and stuff like that. I started playing with her, which was a huge thing that helped my confidence. She continued playing and was in bands in Seattle, and eventually—this jumps forward—she was in Hole, with Courtney Love, in the '90s. She was on the cover of Rolling Stone and playing Saturday Night Live. Her work paid off, where she was playing the Reading Festival and doing it. She's not playing with Courtney anymore, but she still plays, and still gets work. It was a really cool thing to see.

I started a band with friends. My sister was the drummer in that band when we first started. We played parties around Seattle and eventually clubs. A friend of ours had a tiny independent record label and asked us if we wanted to put out a single. He put it out and we got a van and drove to California, did a tour, and got played on the KROQ radio station.

That band was called Sybil, and there's a footnote to that. We put out a full-length record and we had to change the name of the band to Kill Sybil. We had a review in a magazine, Alternative Press, and there was an R&B singer named Sybil who had been around for quite a few years. Her manager called our little independent label and said, “You can't use that name." As a joke, we said, “We could use the name if we killed Sybil," and that became the name of the band. That was my first time in a real studio. It was the Seattle studio, Reciprocal Recording, and Jack Endino, who did some Nirvana and Soundgarden recordings, he had his little protege, Phil Ek. Phil produced our first record. He went on after that to work with Elliot Smith, Modest Mouse, Death Cab for Cutie, and bigger bands. That band, like a lot of bands when you're young, disintegrated in stupid drama, but for that moment it was really cool.

My sister lived in L.A. at the time, since she was in Hole, and they were doing their thing, so as a change of scenery I decided to move to L.A., and I joined a band called the Flesh Eaters. They were a classic L.A. punk band, started in 1977. In the '90s, they were restarting again, and a friend of mine said, “I am in this band, the Flesh Eaters, and they need another guitar player. Do you want to check it out?" I auditioned and got in the Flesh Eaters, and that was another really cool experience, especially in L.A. We played one festival with X, the Bangles, the Weirdos, and even Devo. We did a record, and that was another really cool learning experience. These guys were older, and they'd been around the biz.

Guitars

1990's Fender Telecaster Custom reissue

Amps

Ampeg GVT 1x12

Effects

Boss FZ-5 Fuzz

MXR Carbon Copy

Dunlop Cry Baby Wah

Boss DD-6 Digital Delay

EarthQuaker Devices Ghost Echo

EarthQuaker Devices Data Corrupter

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Super Slinky (.09–.42)

Grey Dunlop .88 mm

My next band was called Midnight Movies. We played in L.A. for a while and got signed to a label. We were going on tour with Blonde Redhead and a lot of these cool indie-type bands. I was working at Amoeba Records in L.A., and the band was really picking up. I had to leave my job, because music was becoming full time, and it was a really weird thing. It was like jumping off a cliff, I thought, “But wait, isn't this what you want? Don't you want to do music for a living?" That was my first moment that was like, “Wow, this is like the real deal." Music became my job. Midnight Movies went on for a couple of years. It was great, we did lots of great tours, made a couple records and EPs, and a lot of stuff happened during that period. That band went on for maybe six or seven years, and then it came to an end.

I was between bands, because it is hard to find the right people, and it takes time to click. It didn't click again until my sister met this girl—they both had kids, and they were at a playdate-type situation and they were talking—and my sister said, “My brother plays music." And the other girl said, “My sister plays music, too." They said, “They should meet." And it was that simple: We met, and just immediately started writing together. That was the start of the Death Valley Girls.

Your sister's friend's sister was Bonnie Bloomgarden?

Yeah, me and Bonnie met, and there was another girl, Rocky, who was Bonnie's friend, and she was our bass player. My sister Patty said, “I am not doing anything right now. I'll sit in on drums and help you write."

Is Patty on your first album?

The first record was actually a cassette called The Street Venom, and she plays on that. She was also playing in another band, called the Upset, and doing other stuff, but she had time to be in the Death Valley Girls during that first six months or so. Things clicked, and me and Bonnie's musical tastes are that we like the exact same stuff. It was that really cool chemistry for writing songs. I would come up with ideas, and she would already have some lyrics to fit. But there was also this other way of writing songs, which I was also doing with Midnight Movies, where Bonnie will sing a song, and a melody into her phone without any musical accompaniment, just a vocal. I go home and put the guitar to it, which is a backwards way of doing it, but I really like doing it that way. If I write a riff or guitar part and give it to the singer, and she has to horseshoe it in, it's like, “How is this going to work? It doesn't fit or this verse has to be longer." But I was doing it backwards, where she sang a melody without the music, and then I'd take it home and put the music to it.

Photo by Debi Del Grande

Is that still how you write today?

Sometimes. A lot of it now is random … it'll be a jam and we take pieces out, and then I go home and write guitar riffs. Bonnie is constantly writing. She has a notebook of lyrics—she has a keyboard at home and she also plays guitar—and she'll come up with rough ideas and give them to me. In my mind, I am drawn to the idea that it has to have a riff, but in the singer-songwriter world, it's about the lyric and word. I understand that, but as a guitar player, I think it's got to have a hook or a riff, so from my side of the writing, that's important.

The new album, Under the Spell of Joy, is riff-centric, and there's not a lot of chord motion. Often it's one theme throughout the song.

Sometimes, when I am critiquing stuff or listening back, and I am stuck on the same theme, I'll think that maybe it needs something else, and I'll nitpick at stuff. But then I go back to some of the bands and music I like, which has a lot of repetition and minimalism: bands like the Velvet Underground and the Stooges. It's all these repeating themes or two chords going back and forth, and it can be as good as any song by Yes. It is about the tension, and if the lyric and melody is strong. Or it's more about the tone, and that's cool. It's about the song. Every song doesn't need a guitar break. Sometimes I have to sit back and think, “The song is great. It doesn't need a crazy noisy solo part. There's no need for that." It's an ego thing. I don't have to put my stamp all over certain things. You have to let go of that. On the new record there are songs that are spacey and ambient and a lot of keyboard and sax, where the guitar is there, and playing a few chords to put the bed in. It doesn't have to be front and center.

Live at Joshua Tree's Desert Daze Festival in 2017, Death Valley Girls make the most of cramped quarters by rocking big on “Street Justice" from 2018's Darkness Rains. Note Larry Schemel's pedals are on the floor of their stage inside a van, and his Tele Custom reissue is slung over his shoulders.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)