Tune-o-matic bridges are common on many guitars, including Gibson Les Paul, SG, and Firebird models. They come in several styles and shapes, depending on the guitar. Some Tune-o-matics have a retaining wire (the vintage ABR-1, for example), others have self-contained saddles like the Nashville Tune-o-matic. No matter what style Tune-o-matic your guitar has, it's important to regularly inspect the bridge for wear. Eventually, you may need to replace it—we'll see why in a moment.

It's not hard to install a Tune-o-matic, if you know what's required and how to avoid a few pitfalls. Let's explore these points, using a 1960 Gibson Les Paul Classic model (Fig. 1) as our project guitar. Note: These techniques apply to any guitar equipped with a Tune-o-matic-style bridge.

Getting started.

The first step in any repair or upgrade is to evaluate the guitar. As part of this process, I always measure the action at the 12th fret, the neck relief, the action at the 1st fret, and also check the intonation.

From this preliminary evaluation I discovered that the action at the 12th fret on this Les Paul was 4/64" on the 1st string, 3/64" for the 3rd and 4th strings, and 5/64" for the 6th string. This is high action! In addition, the 3rd and 4th strings were much lower than the rest. This was caused by a bad case of what I call "smiling bridge syndrome." That's where the bridge begins to warp between the adjustment posts. (For more details, see the sidebar at the end of this article.)

The best way to correct this problem? Replace the bridge.

Installing the new Tune-o-matic.

For this Les Paul, I chose a Schaller Nashville Tunematic—a high-quality bridge that should last longer than the typical replacement units. When replacing a Tune-o-matic-style bridge, you need to consider several critical variables: string spacing, string angle, and the slot width.

String spacing is the distance between the strings in relation to the fretboard. This is critical: When the strings aren't aligned properly, one of the E strings can slip off the fretboard or the pickup may produce uneven string-to-string volume. At the very least, playability will suffer.

String angle describes the path each string follows from the tailpiece to the top of the bridge saddles. If this angle is not carved properly in the backside of the saddle, strings can break and you may have problems keeping the guitar in tune.

The width of the slots in each saddle is also very important. Each slot carved into the saddles should precisely match the gauge of its respective string. When a slot is too narrow, the string will bind, causing tuning problems and string breakage. When the slot is too wide, the string can rattle, buzz, and slide sideways when you bend notes.

Here's how I determine the proper spacing, angle, and slot width for each string and saddle: First I remove the old bridge, install the new one, tune the guitar, and adjust the string height at the 12th-fret roughly where my client wants it. For this guitar, that was 3/64" for the 1st string and 4/64" for the 6th string.

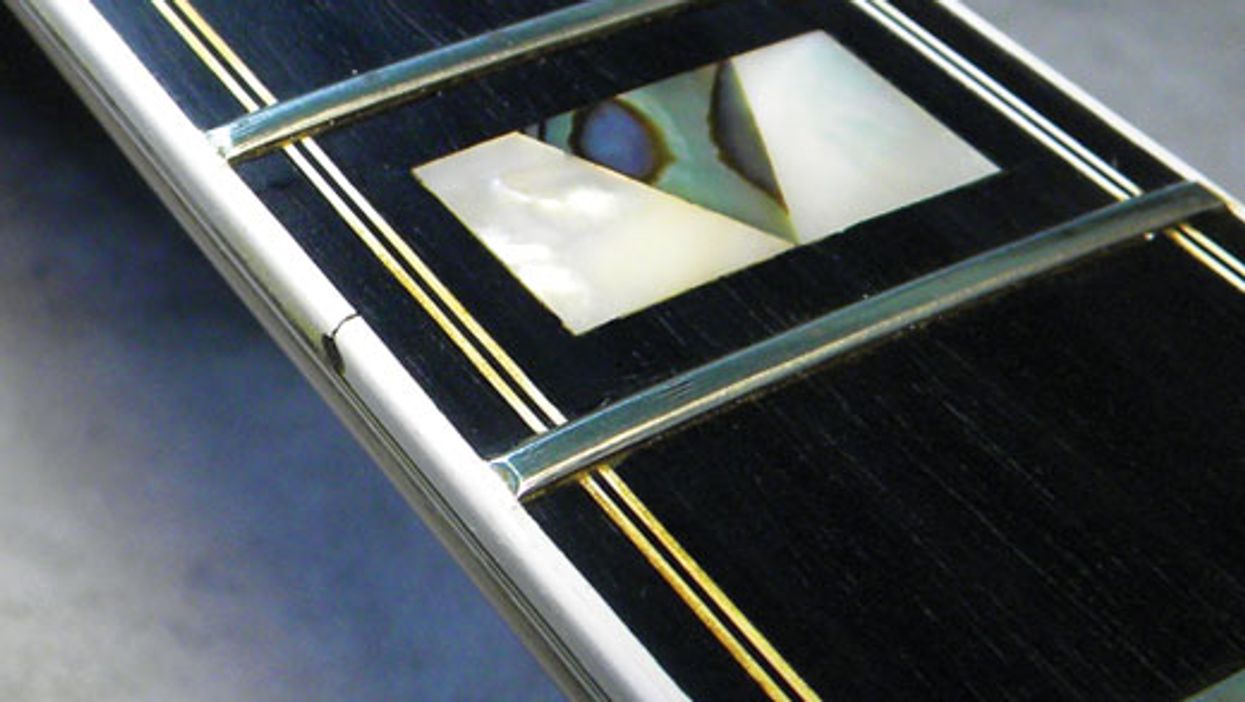

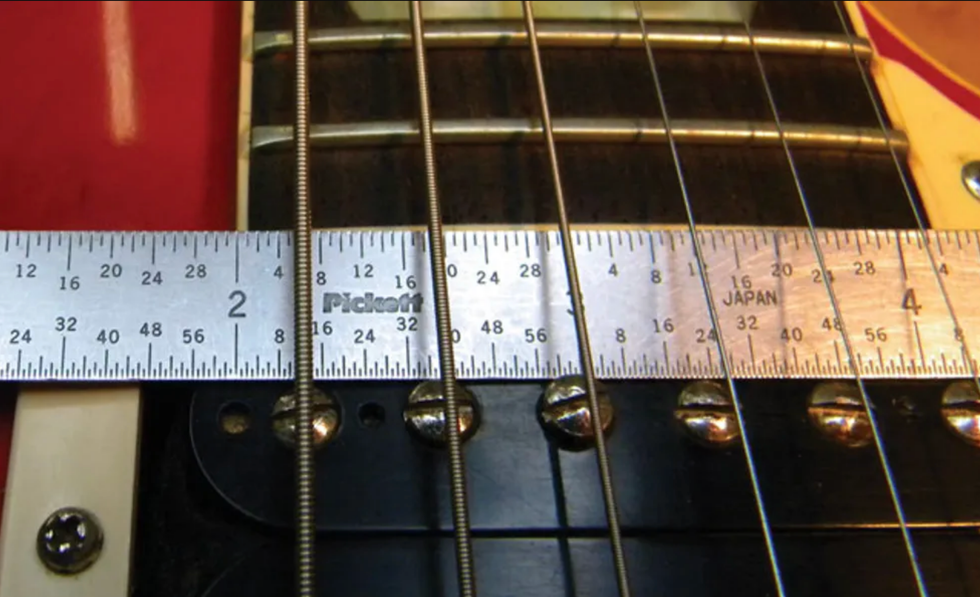

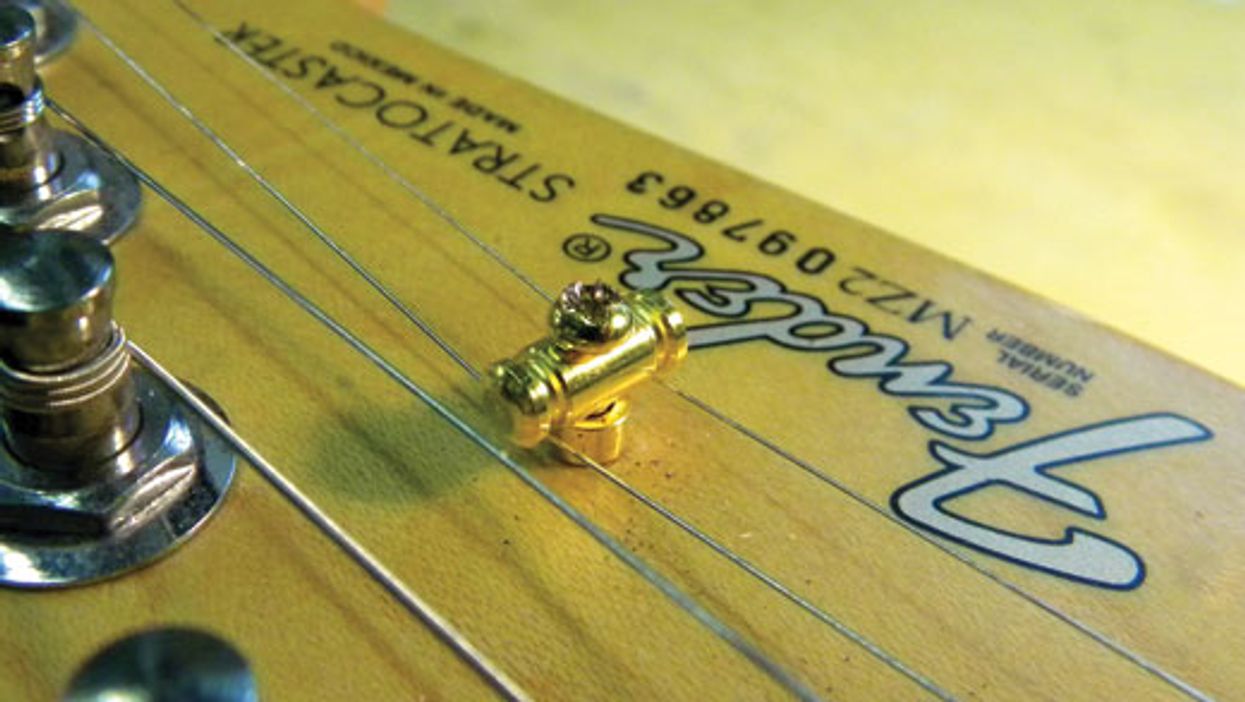

Fig. 2: Measuring the space between the edge of the fretboard and the two outside strings.

Next I measure the distance at the last fret from the edge of the fretboard to the outside edge of the 1st and 6th strings (Fig. 2). It's important that both strings are the same distance from the edge of the fretboard—approximately 1/8" in is a good starting point. Each guitar will vary slightly, depending on the width of its neck, but the key is equal spacing from the outside edge of the string to the edge of the fretboard. Again, this applies to both strings.

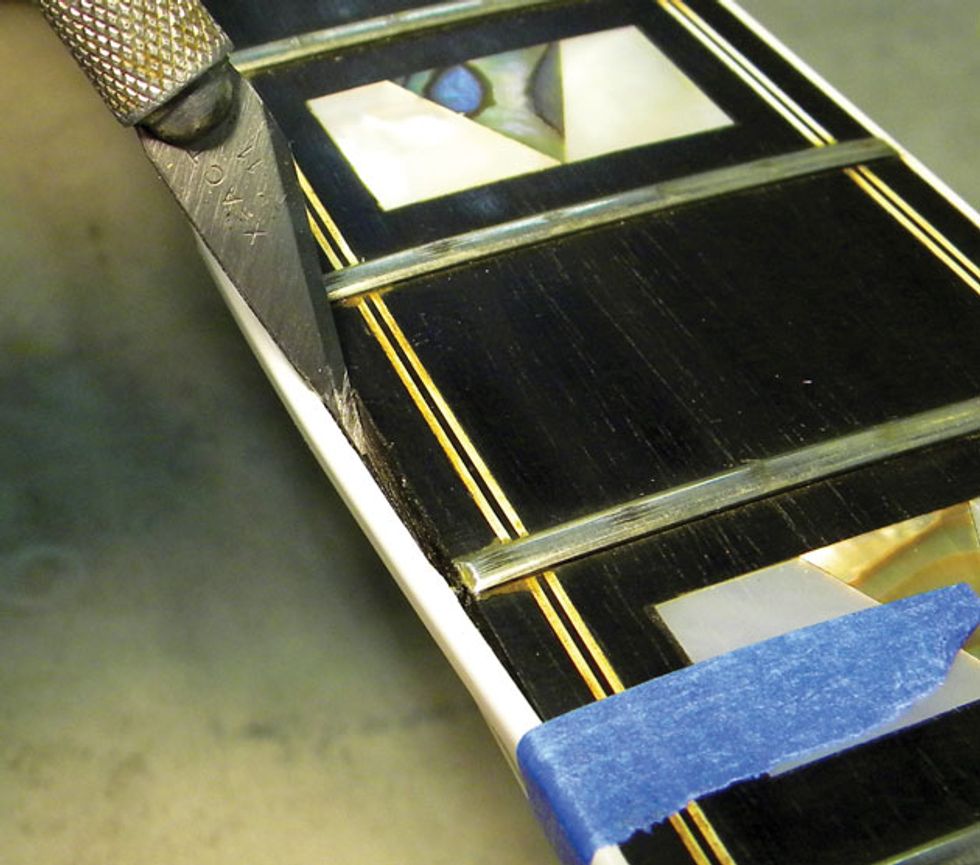

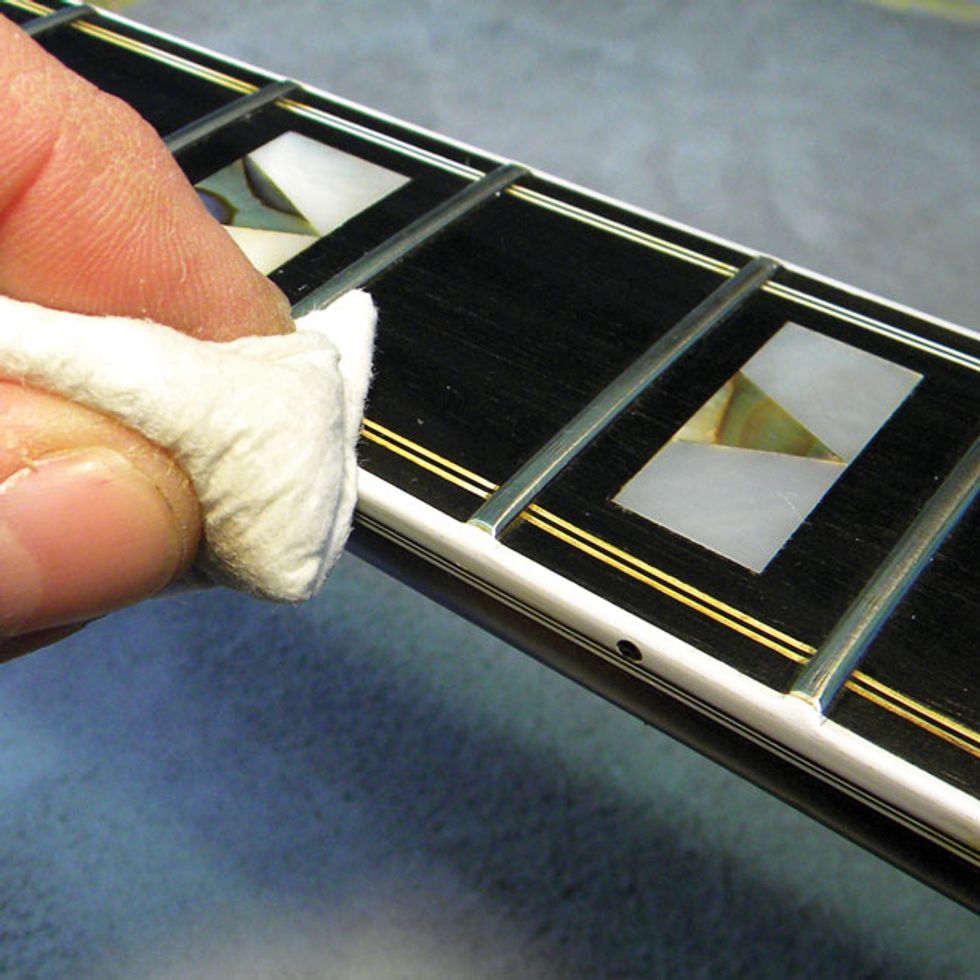

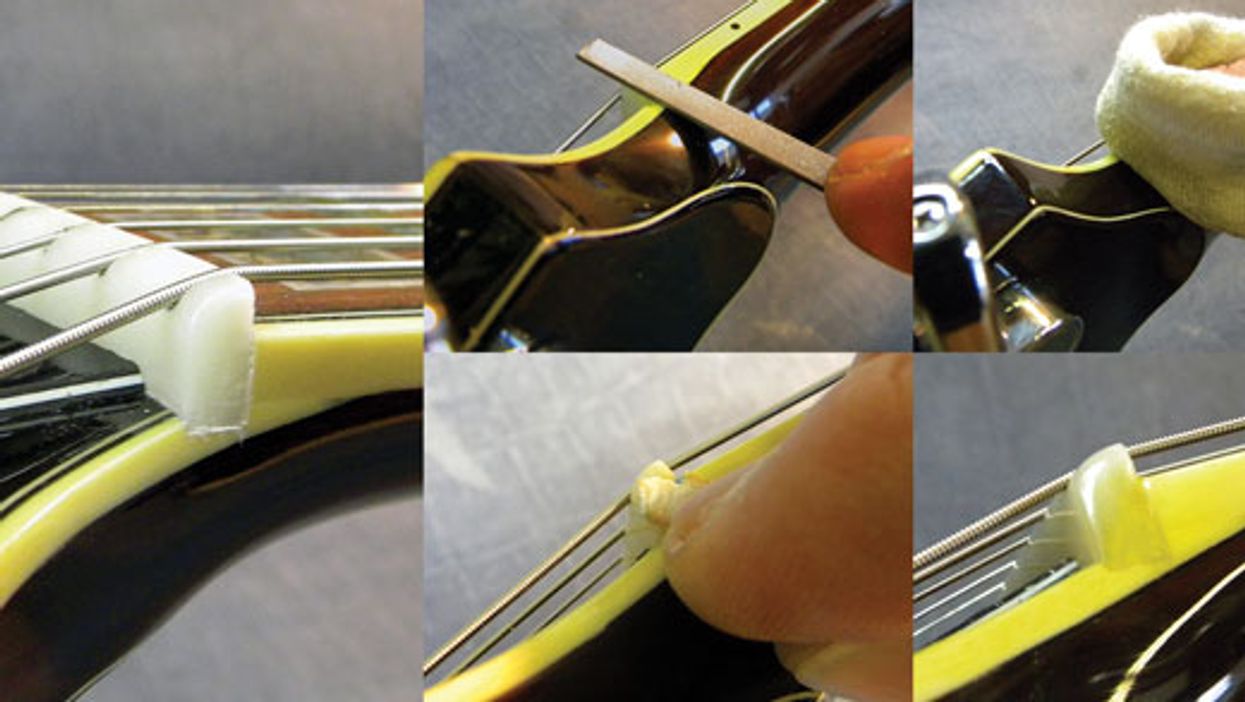

Fig. 3: Gauged nut files, which are available from luthier supply shops, are ideal for cutting the string slots in new saddles.

To seat the 1st and 6th strings, I then carve a very shallow slot into their saddles. I use nut files for this (Fig. 3)—a .010" file for the 1st saddle and a .046" for the 6th.

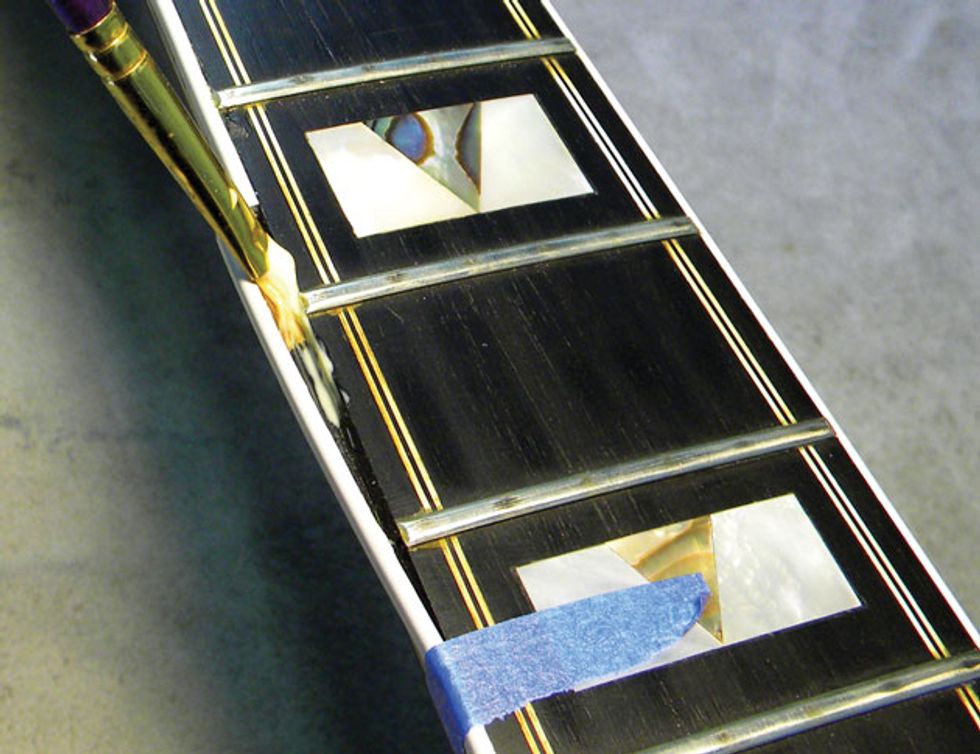

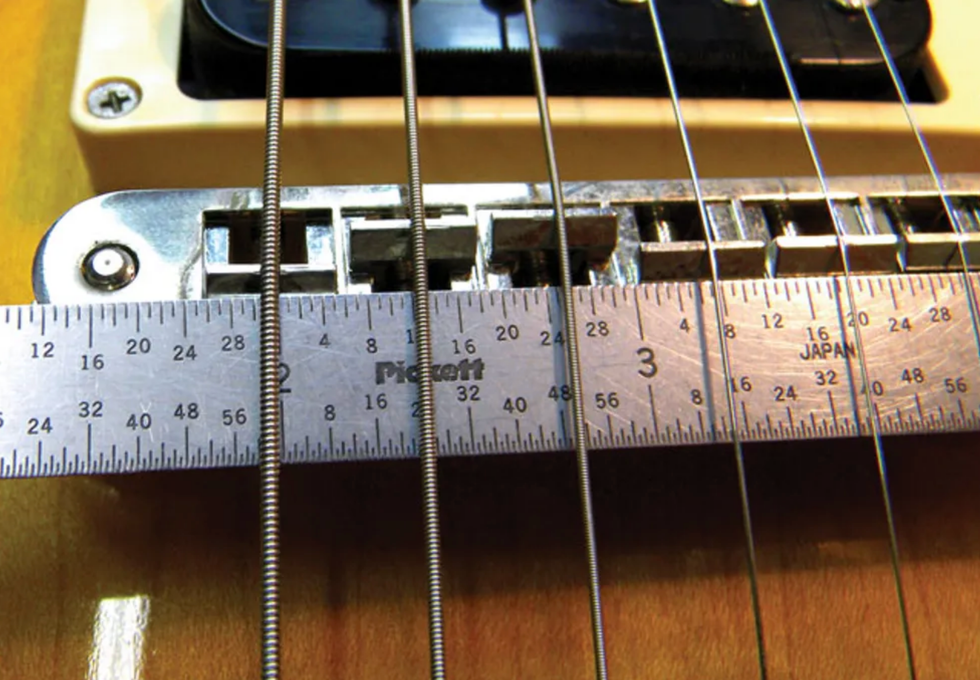

Fig. 4: Measuring the space between the edges of adjacent strings. The distance should be identical between all strings, so don't measure from the center of each string, as this will result in the bass strings being closer together than the treble strings.

Once the outside strings are set, I position the inside four strings over the unslotted saddles until the strings are equidistantly spaced, measuring from the outside edge of each adjacent string. These five gaps will be approximately 25/64" (Fig. 4). Do not measure from the center of each string, as this will result in the bass strings being closer together than the treble strings.

After I've measured the spacing—and double-checked it with a ruler—I cut a shallow slot into each saddle using nut files that match the gauge of each string.

Caution: If you're unsure about filing the string slots, consult a qualified tech or luthier. If you make a mistake with the slots, you may have to start over with a new Tune-o-matic or at least new saddles.

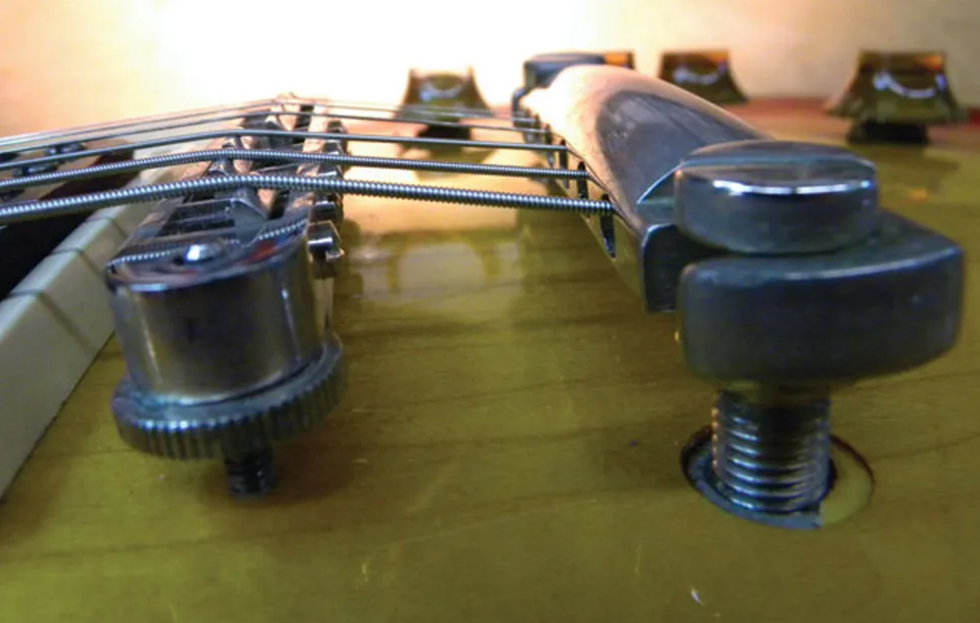

Fig. 5: Set the tailpiece height so no strings rest against the rear of the bridge frame. The only point of contact for each string should be the top of its respective saddle.

Pay close attention to the angle of each string in relation to the tailpiece. The tailpiece should be adjusted so the strings never touch the rear edge of the Tune-o-matic. Contact here can cause tuning problems, so all the strings need to clear the bridge frame (Fig. 5).

Fig. 6: File the saddle slots to allow each string to follow its natural angle to the tailpiece.

When the tailpiece is adjusted, I finish filing the string slots. This involves carefully sloping down the back of the slots to allow each string to follow its natural angle as it emerges from the tailpiece to the point where it contacts the saddle (Fig. 6).

Adjusting intonation.

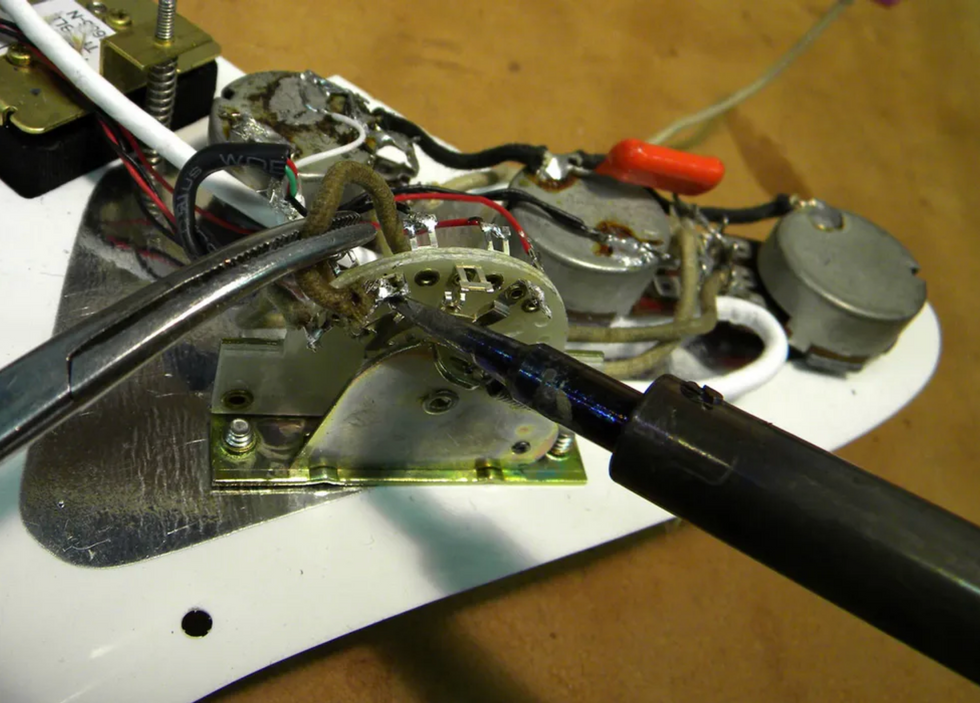

The final step is to intonate the guitar by moving the new saddles forward or backward in the bridge to shorten or lengthen the vibrating portion of the string. The saddle-intonation adjustment screw is located at the rear of the bridge, and the idea is to move each saddle forward (by turning the screw counterclockwise) or backward (clockwise) using a small screwdriver. (Typically it's a Phillips or flathead, depending on the make and model of the bridge.)

Here's how to set the intonation:

- Using a high-quality electronic tuner, bring each string to pitch. But instead of playing an open string and tuning it, strike the 12th-fret harmonic and tune it to pitch.

- Starting with the 1st string, play the 12th-fret harmonic and then fret and pluck the same note. If the fretted note is sharp compared to the harmonic, move the saddle away from the neck. Conversely, if the fretted note is flat, move the saddle toward the neck. Make small adjustments and retune the harmonic each time you make an adjustment. Continue comparing the 12th-fret note to its reference harmonic until the former matches the latter.

- Repeat this process until all the 12th-fret notes on all six strings match their corresponding 12th-fret harmonics.

Once the strings are intonated and you've confirmed they're spaced, seated, and angled correctly, you're good to go with your new Tune-o-matic.

Smiling Bridge Syndrome

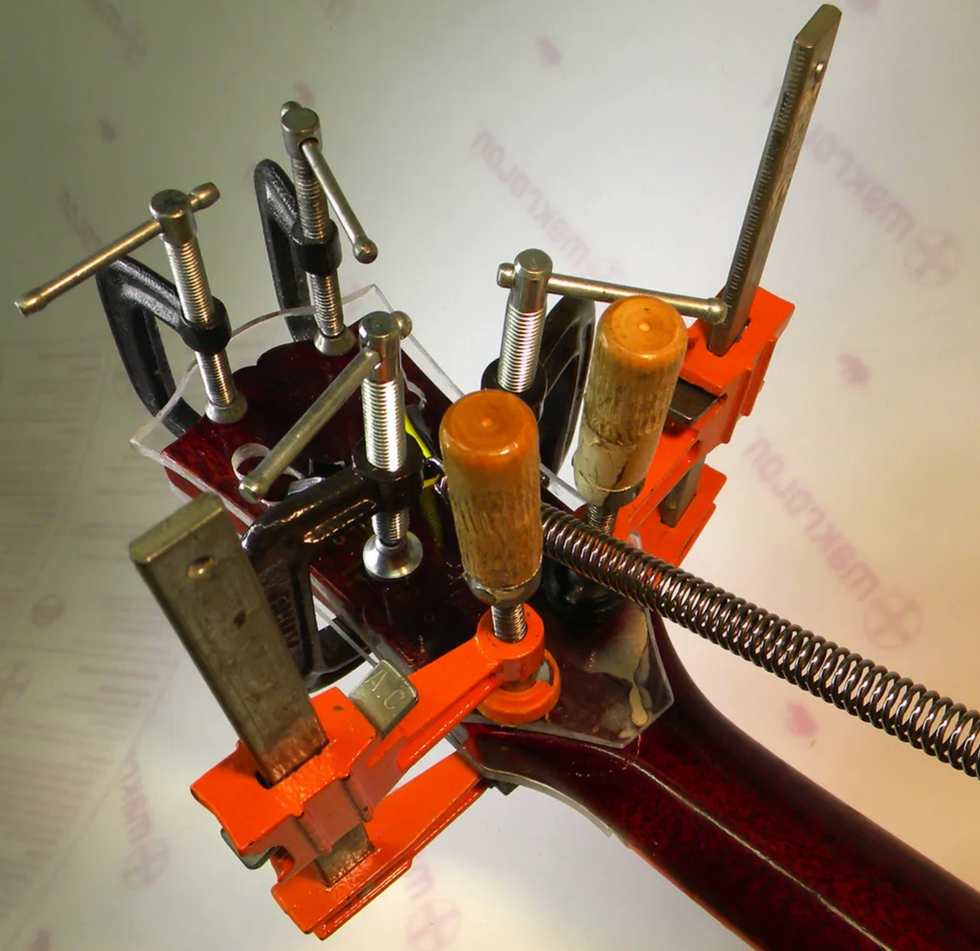

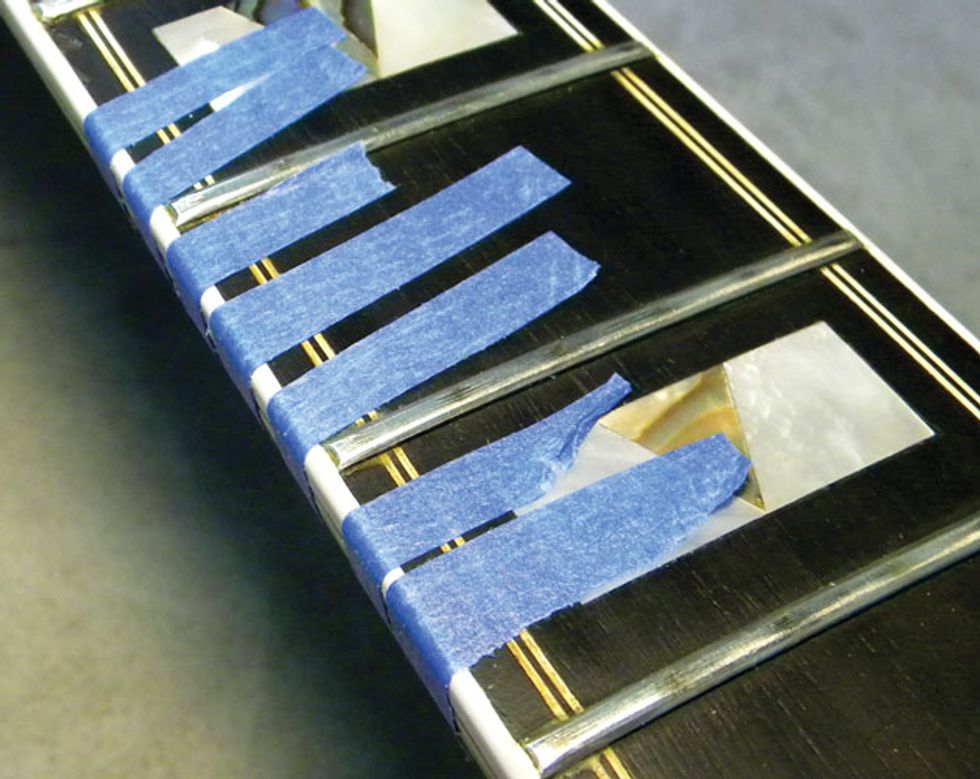

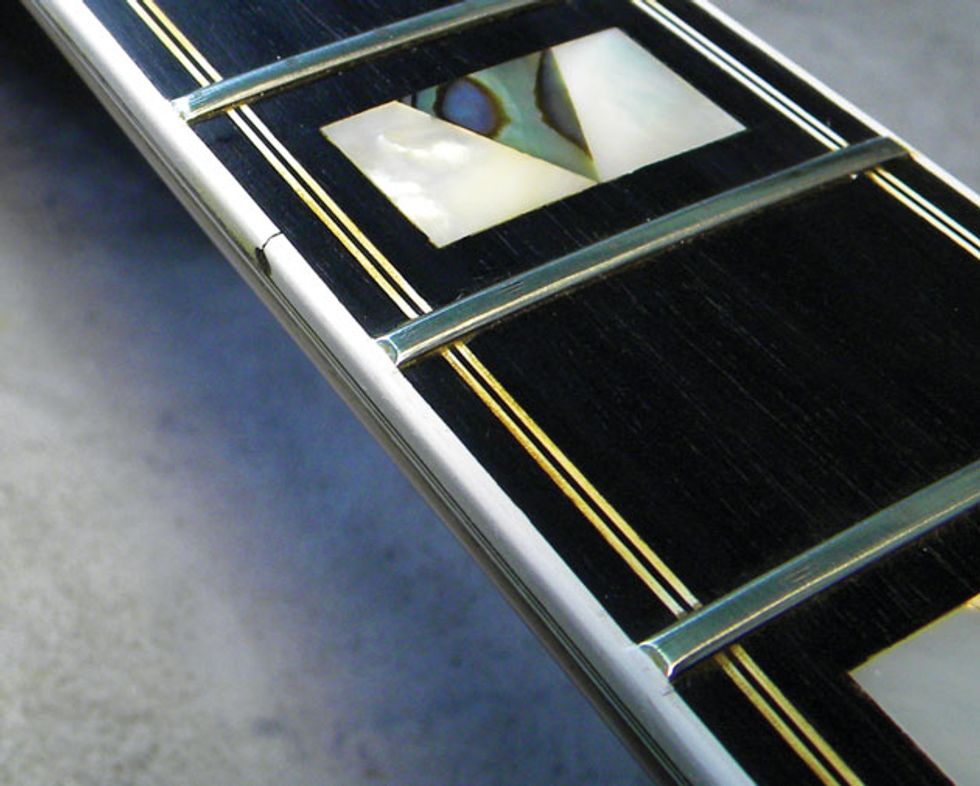

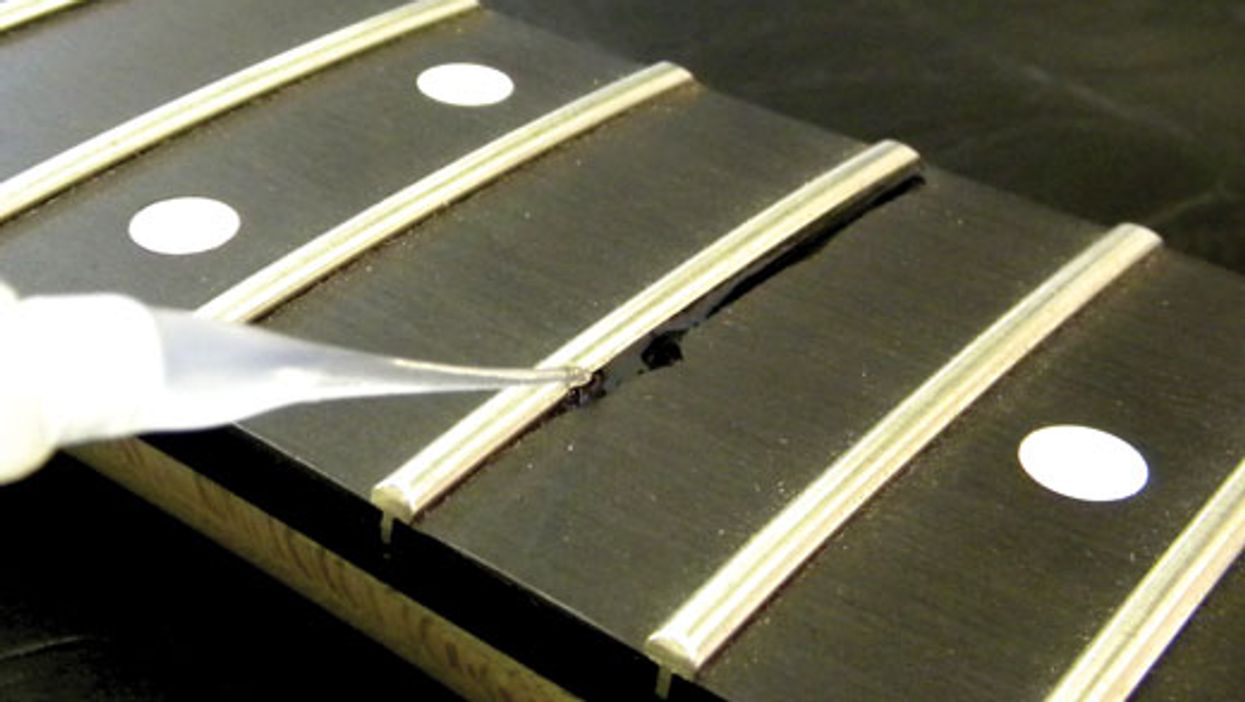

Fig. 7: See the gap in the middle of the bridge between the ruler and frame? Years of string pressure have caused this bridge to collapse, dropping the middle strings lower than the outside strings.

The last thing you want to see is your Tune-o-matic smiling ... as if to mock you! When this happens, it means the bridge has collapsed, causing the action of the middle strings to drop lower than the outside strings. Many Tune-o-matic-style bridges are made of zinc—a metal that's softer than steel—and years of downward string pressure can destroy the bridge's built-in radius that's designed to match your fretboard.

You can check this with a 6" machinist's metal ruler. Fig. 7 shows the original, collapsed Les Paul bridge, and the large gap between the ruler and the top of the bridge frame reveals the problem.

Fig. 8: This new bridge has no gap. Once it's installed, the Les Paul will be playable again.

Notice how the ruler lies flat against the top of the new replacement bridge (Fig. 8).

[Updated 10/22/21]

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)