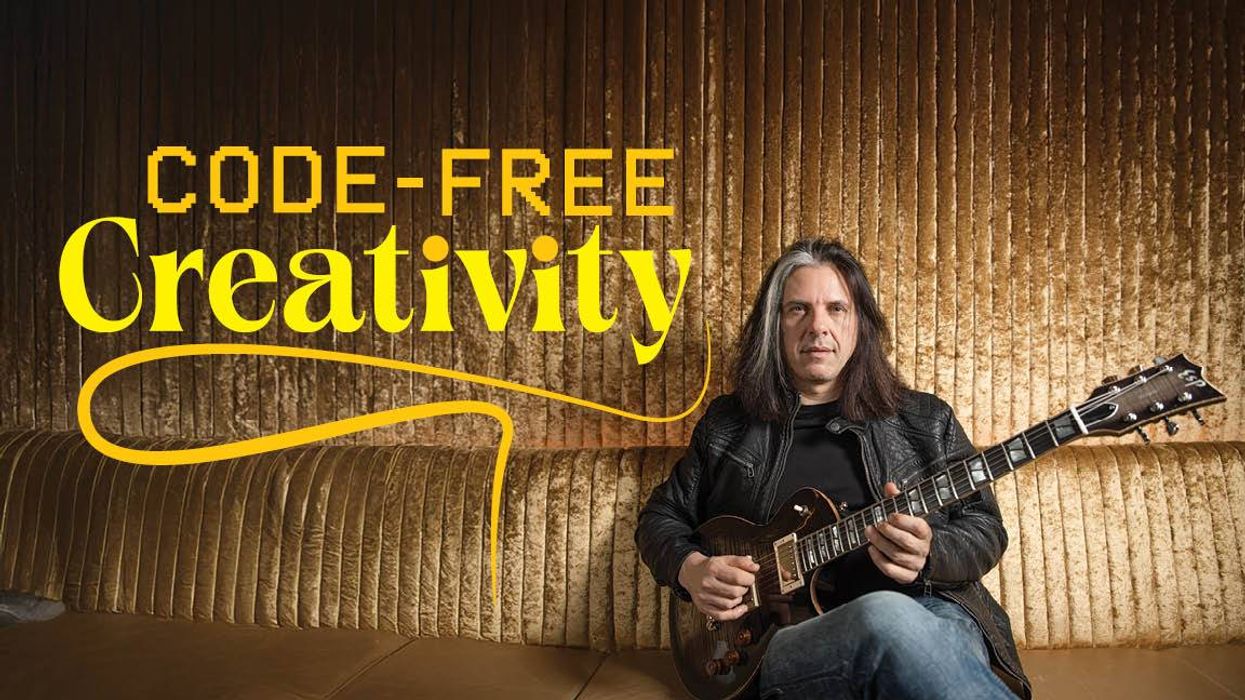

When Jim Campilongo phones in with Premier Guitar, it’s from his home in the Bay Area—the same place where he first picked up the guitar in the 1970s, began playing shows with local groups some years later and, eventually, launched his recording career in the 1990s. Over the subsequent decades, he established himself as one of the instrument’s foremost creatives, building a catalog of primarily instrumental albums that encompass a dazzling array of styles—rock, jazz, roots, Western swing, classical, experimental—all informed by his inventive, flexible and never-predictable playing, mostly on a Fender Telecaster plugged direct into an amp.

He did this largely in his adopted home of New York City, where, for most of the 2000s, he was a mainstay—and, for music fans in the know, a must-see—of the downtown arts scene, with long-running and celebrated residencies at Lower East Side venues like Rockwood Music Hall and the now-defunct Living Room.

Campilongo left the East Coast to return West roughly two years ago. But his newest record, She Loved the Coney Island Freak Show, is very much a New York album—maybe his most New York one of all. It is also very much a rock album—maybe his most rock one of all. There are reasons for this. The roots of the record stretch back to the dark days of Covid, when words like “quarantine” and “distancing” were too much a part of the common vernacular. Life was weirder, quieter and, truth be told, often drearier. Campilongo found escape where he could, which manifested in daily 5 a.m. walks around his Brooklyn neighborhood. His companion was an old iPod playlist of classic-rock songs. “I’d go out, it’d be pitch black, there’d be no one around—it was like a science-fiction movie,” he recalls. “I had these old-school Vic Firth headphones, and an iPod that had a playlist of maybe 300 classic-rock tunes that I made back when iPods were the latest thing. And I would walk the streets listening to it over and over.”

The 4TET, from left to right: drummer Dan Rieser, Campilongo, bassist Andy Hess, and guitarist Luca Benedetti.

Some of the songs that, quite literally, got into Campilongo’s head? “It was ‘Mississippi Queen’ kind of stuff,” he says. “‘Hush’ by Deep Purple. Elvin Bishop’s ‘Travelin’ Shoes,’ which is an amazingly eventful track. There’s background vocals, there’s a little breakdown, there’s a melodic solo. There’s harmonies, a great rhythm.... I became obsessed with it.”

These songs, and the 297 or so others on Campilongo’s playlist, informed several of the tracks on She Loved the Coney Island Freak Show. One, a greasy, growly workout titled “This Is a Quiet Street,” was influenced by Grand Funk Railroad’s live version of the Animals’ 1966 single, “Inside Looking Out”—“a song I’ve been listening to since high school, and that I’ve been trying to write for 20 years,” Campilongo says. “This is about the closest I’ve gotten.” Another track, “Do Not Disturb,” he continues, “is like my interpretation of a ZZ Top tune.”

“I’d go out, it’d be pitch black, there’d be no one around—it was like a science-fiction movie.... And I would walk the streets listening to it over and over.”

But She Loves the Coney Island Freak Show is not all rock-influenced. Leadoff track “Dragon Stamp,” a dark, deep-in-the-pocket jam that Campilongo introduces by sounding a detuned open low string, and then hitting a harmonic and raising the pitch by bending the string behind the nut (something of a JC trademark move), came to Campilongo after repeated playings of “Step to Me,” a 1991 song from deceased New York hardcore rapper Tim Dog, on his early morning walks. “I think I listened to that 50 times in a row, numerous times,” Campilongo says. “I couldn’t get enough of it.” The emotive “Sunset Park,” meanwhile, in which Campilongo unspools languid, vocal guitar lines in a manner that is nothing short of a master class in the subtle art of touch, tone and phrasing, was influenced by a Maria Callas aria. Another track, “Sal’s Waltz,” by Frédéric Chopin. “Whether it’s successful or not, who knows?” Campilongo says self-effacingly.

Sunset Park

While many of the She Loved the Coney Island Freak Show songs have their origins in Campilongo’s early-morning walks and his iPod-provided soundtrack, bringing them into existence was in some ways a more immediate affair. To record the album, Campilongo got together with guitarist and longtime collaborator Luca Benedetti, bassist Andy Hess, and drummer Dan Rieser in a combo they dubbed the 4TET, and laid down the tracks live in the studio—two studios, to be exact. “We did two days recording at Bunker [in Williamsburg, Brooklyn], and then another two days at a different studio [Atomic Sound, in Red Hook, Brooklyn],” he says. “It was pure joy to play with those guys.”

“I always figured I could get all the sounds I want from the volume and tone knobs on the guitar, or from where I pick, and how hard; all those little variations.”

Campilongo, as is his way, kept his gear setup minimal: his trusty 1959 Fender Telecaster with a top-loader bridge, plugged straight into a 1970 silver-panel Fender Princeton Reverb fitted with a Celestion G10 speaker—no pedals required. “It’s so uninteresting for me to talk about gear, because it’s basically the same answer every time,” he says with a laugh. As for why he mostly eschews effects? “I always figured I could get all the sounds I want from the volume and tone knobs on the guitar—and on a Tele, those knobs are really dramatic—or from where I pick, and how hard; all those little variations,” he reasons. Another benefit of going sans pedals? “You kind of just accept the hand you’re dealt, and you can get down to playing music quicker.”

When it came to the playing, Campilongo stuck to another tried-and-true aspect of his guitar style—improvisation. “None of what I’m doing on the album was worked out beforehand,” he says of his solos on She Loved the Coney Island Freak Show. In his opinion, this makes for not only a better playing experience, but a better listening one, too. “If I play a perfect solo and it’s worked out, I generally don’t like listening to it, because it’s not a time capsule of that moment,” he says. “It’s like going out on a first date and having a script of what to talk about, instead of it just being a natural conversation. I want to hear the real talk, warts and all.”

Jim Campilongo's Gear

Campilongo performing at Rockwood Music Hall Stage 3, the same Lower East Side venue where he previously held a long-running residency.

Photo by Manish Gosalia

Guitars

- 1959 Fender Telecaster

- Lumiere Jim Campilongo Signature T- Model

- Fender Custom Shop Jim Campilongo Signature Telecaster

Amps

Effects

- Crazy Tube Circuits Splash Reverb

- Crazy Tube Circuits Stardust Overdrive

- JAM Pedals Wahcko

- Universal Audio OX Amp Top Box

- Boomerang Phrase Sampler

Strings, Picks, & Accessories

- D’Addario EXL120 Nickel Wound Super Light (.009–.042)

- V-Picks Fusion

- Klotz Titanium guitar cable

- Souldier guitar straps

Campilongo’s commitment to balancing on that creative knife edge informs every aspect of the album, and also his music in general. “I don’t want to ever put out the same record twice in a row,” he says. To that end, he is already plotting future challenges, including a “pseudo-jazz record where I’m playing standards in the way I would present them, which would be a little scary.”

For all his musical adventurism, one aspect of Campilongo’s artistic makeup that remains steadfast is his connection to the city that helped birth She Loved the Coney Island Freak Show. “Even though I’m back in California, in many ways I feel like a transplanted New Yorker,” Campilongo says. “It’s in my DNA,” he laughs. “It’s not like I’m returning home to the West Coast and, you know, I can’t wait to go surfing.”

YouTube It

For years, Jim Campilongo held court at New York City’s Rockwood Music Hall. Here, Jim and the 4TET tear through a She Loved the Coney Island Freak Show highlight: the Southern-rock-inflected, ZZ Top-inspired “Do Not Disturb.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)