There’s a dangerous, pernicious myth, seemingly spread in perpetuity among fledgling artists and music fans alike, that when you’re a musician, inspiration—and therefore productivity—comes naturally. Making art is the opposite of work, and, conversely, we know what happens to Jack when there’s all work and no play. But what happens when the dimensions of work and play fuse together like time and space? What happens to Jack then? Well, behind such an instance of metaphysical reaction, undoubtedly, would be King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard.

King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard - Le Risque (Official Video)

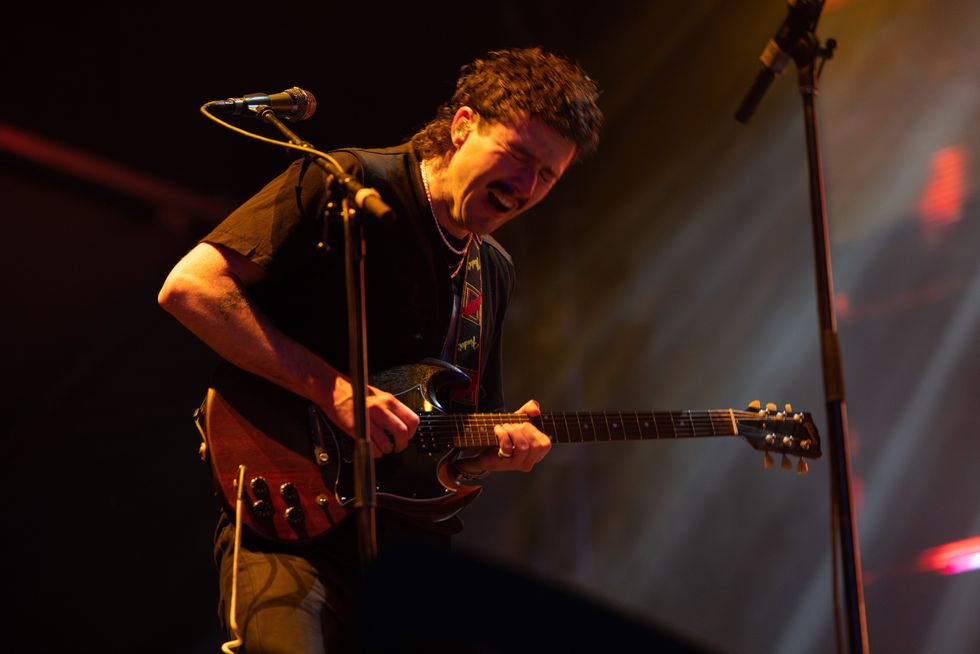

On the day that I connect with King Gizzard's guitarists and songwriters Joey Walker and Stu Mackenzie, they're settling into their hotel in Paris, after arriving on their tour bus that morning. As two of six bandmates of the psychedelic, maniacally chimerical Australian band, their work is rambunctiously genre-agnostic—with records falling into garage rock, prog-rock, folk, heavy-metal, and jazz-fusion categories. Celebrated in part for their unfaltering output of releases since their inception 14 years ago, they have 25 studio and 15 live albums to their name. We’re meeting to talk about the release of their 26th studio album, Flight b741.

In my conversation with Walker, who I speak with one-on-one a few hours before I have my call with Mackenzie, I comment, “You guys are known for putting music out like crazy. And you have this whole fun energy about your sound that could be misleading to fans—as if you’re just goofing off and succeeding—but you must have an incredible work ethic.”

“When I’m not in the studio, I’m making music as well. The beauty is that we really love each other’s company and just enjoy doing it.” —Joey Walker

“Gizzard is an example of a band where we just work really hard,” he reflects back. “There’s no other answer. People are like, ‘How the fuck do you put out so much music?’ We just go to the studio heaps, and make heaps of music together, and when I’m not in the studio, I’m making music as well. The beauty is that we really love each other’s company and just enjoy doing it.”

Of course, like most of King Gizzard’s catalog, on Flight b741 all you can hear is the fun. The album rings like an amusement park of classic rock and Americana, knitted together with full-band vocal harmonies appearing throughout—like a family choir—and chords echoing in the many familiar furrows of folk tradition. And yet, the band perhaps takes a page from the Kinks’ library, where the words underpinning that joyful music can often get a bit grim. For one, “Antarctica” is about climate change, with the lyrics, “Take me away / I wanna feel them frost flakes on my face again / Take me away / Where the temperature stays below 25/78,” and “I know this ain’t gonna go well / Snowball’s chance in hell.” The title track is a tale sung in first person by a forlorn pilot: “This plane is going down with me on / The splatter of the engine and the creaking of the skeleton, composing a requiem / I’m frightened.”

Joey Walker's Gear

Joey Walker says the band puts out as much music as they do through sheer dedication, motivated by the joy it brings them to create together.

Photo by Tim Bugbee

Guitars

- 2002 Gibson Flying V

- 2011 Gibson Explorer

- Godin Richmond Dorchester modded “Dickhead” microtonal guitar

Amps

- Fender Hot Rod Deluxe 1x12

- Hiwatt DR504 combo

Effects

- Boss TU-3

- Dunlop Cry Baby Wah

- Strymon Sunset Dual Overdrive

- Wampler Faux AnalogEcho

- Electro-Harmonix Flatiron Fuzz

Strings

- Ernie Ball Strings

As for the vocal parts, they indeed include every member of the band. As Walker explains, “We rely heavily on a conceptual thing to get going with a record. It makes it easier for us to cauterize an idea if there’s a limitation we impose. [For this record, we thought,] ‘What if, at multiple times throughout each song, there was a shift in who was the lead singer?’ So we’ve got our drummer Michael Cavanagh singing for the first time. Our bass player Lucas [Harwood] is singing on his first Gizzard song as well, and we all just had a big week of doing harmonies.”

When I connect with Mackenzie later in the day, he tells me, “It was all six of us standing around two microphones. We printed out all the lyrics and just stood there—it took us like four days—until the vocals were done.”

I mention that the album reminds me specifically of the spirit of Pink Floyd’s Meddle (but supercharged), and Walker obliges that there’s plenty of ’60s and ’70s rock influence present on Flight b741, adding that the trap they could have fallen into in is writing “some horrible, derivative” Rolling Stones-knockoff material. “But the thing with King Gizzard is trying to find whatever little angle you can slot into something that might be cliché or corny, and then subvert it,” he says. “And we have faith, since we’ve been doing it for so long and we know each other so well, that it’ll end up being a King Gizzard album.”

Both Mackenzie and Walker mention the band name frequently in their interviews, using a small assortment of nicknames: King Gizzard, King Gizz, Gizzard, Gizz … as if it’s a living and breathing creature who gobbles up musical ideas and births offspring in the form of spotlessly effusive, cheeky records. Maybe it feels that way to them, like how writers of narrative fiction often find that the more they visualize their characters, the more the characters seem to start acting out a plot on their own.

When King Gizzard’s characters met, they were students at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology. “We all lived in share houses around Melbourne and were in more ‘serious’ bands, and then King Gizzard was the joke party band, hence the name,” Walker shares, smiling. “And … now the joke’s on us.”

King Gizzard’s 26th studio album, Flight b741 dips into folk, classic rock, and Americana territory.

As we cover ground on the topic of creative flow and how it relates to King Gizzard’s productivity, Walker and I get to talking about what it means to grapple with fears as an amateur artist, and what it’s like when you’re starting out and no one’s really paying attention to you.

“That’s where we started,” he says. “So many artists—broad term, ‘artists’—are crippled by their inability to let go of how stuff will be perceived, when most likely there won’t be anyone to perceive it, so they just don’t do anything. I get it, your song isn’t finished yet. It’s never going to be finished. You have to make stuff that necessarily might not be your best work; you have to feel like that to make your best work. Don’t be paralyzed by perception or fears.”

It’s clear in our conversation that King Gizzard’s output is fueled by the bandmates’ pure joy in making music together. So, is their love for one another essentially what’s at the heart of it all?

“Love, and perpetually being inspired by each other, as well,” Walker shares. “Stu kind of operates on a different strata of consciousness or something, just in terms of his approach to making music and stuff. If I hadn’t met him, I would have probably succumbed to that [state of being a] person that couldn’t finish that first song and never do anything. He’s completely unbridled or unbound by how things are perceived. There’s been a lot of teaching. We teach each other a lot, and we just kind of take little parts—and the amorphous whole of us becomes King Gizzard.”

When I share Walker’s comments with Mackenzie later in the day, he doesn’t seem fazed by his friend’s sentiments; my guess is that’s because he already knows how much Walker values their bond, and vice versa.

Stu Mackenzie's Gear

Mackenzie—pictured here making a whimsical “blep”—says the lessons he learned during the time he spent teaching as a teenager largely inform his guitar playing today.

Photo by Debi Del Grande

Guitars

- '67 Yamaha SG-2A Flying Samurai

- Gibson SG-3

- Custom-built Flying Microtonal Banana with additional microtonal frets

Amps

- Fender Hot Rod Deluxe 1x12

Effects

- Boss TU-3

- Boss DD-3

- Devi Ever FX Torn’s Peaker

- Fender Tread-Light Wah

- Strymon blueSky

- VVco Pedals Time Box

Strings & Accessories

Ernie Ball Strings- Divine Noise Cables

“That’s nice of him [laughs],” he says. “I think we all have spurred each other on in lovely ways and have been really inspired by each other in different, changing ways over the years, too.

“The six of us; they are my best friends, so I love them all and care for them all so, so deeply,” he continues. “And there really is just a lot of respect for each other, but that’s not to say that it’s always easy. My role has always been to be that kind of middle person and to mediate those incredible, creative minds, and make sure everyone feels heard, and ideas are being listened to even if they’re not used. It’s honestly a really, really challenging balance to keep a lot of the time.”

But, he adds, “I know this is a very privileged position to be in, to be artists full-time. The moment I feel like we take our foot off the gas, I will start to feel … guilty, like I don’t deserve to be here anymore. But we’re all workin’ our butts off. I’m here for it.”

The Lizard Wizard’s magic wands include an oddball array of guitars, including one set up for microtonal playing.

Photo by Maclay Heriot

Historically, there are actually three guitarists in King Gizzard—Walker, Mackenzie, and Cook Craig—but for Flight b741 Craig (or, as he’s called, “Cookie”) stuck to organ, Mellotron, vocals, and bass (for one song). Yet, neither Walker nor Mackenzie care much about analyzing their guitars or guitar playing. (Perhaps, King Gizzard hasn’t gotten this far in life by preoccupying themselves with analytics.)

“I’m always down to do stuff like this with guitar-based publications,” says Walker, at the beginning of our conversation. “But I feel like, if they want to get granular about guitar.... I play guitar, I love guitar, but I don’t think about guitar a huge amount, you know what I mean?”

When I ask Mackenzie asked about what informs his guitar playing, he rewinds the clock a bit. He explains that he began teaching guitar as a teenager, where he spent most of his time breaking down classic rock songs for his students to learn. “In hindsight, I was sitting down with a guitar for sometimes five straight hours, just deconstructing songs. And, learning the construction of songs and the way that comes together; I still think about guitar in that same way when we’re playing.

“For instance, the King Gizzard show has gotten quite improvised,” he elaborates. “And I’m still thinking about structure when we’re jamming. I’m trying to take things away from being linear. Linear’s great—we’ve made linear songs, too; that’s totally fine. But I’m kind of an old-fashioned guy when it comes to song structure. I do like songs to come back and for things to repeat and to have structure you can kind of grab onto.”

“How do you make a record that still feels like a whole, still feels like a universe in itself, but doesn’t sound like anything that you’ve done before?” —Stu Mackenzie

As a young teenager, Mackenzie loved bands like Slayer and Rammstein, and soon after discovered Tool, which led him “backwards” into King Crimson and other ’70s prog artists. But later in his adolescence, he grew into the belief that “all of the best music” was made between 1964 and 1969. “I would say there was a two, maybe three-year period where I didn’t listen to anything that was outside of those years, which is kind of crazy,” he says. In particular, he was fascinated with the “post-Beatles, post-Beach Boys era of amateur American garage rock.” Immersing himself in that world, he dug into obscure compilations like Nuggets: Original Artyfacts from the First Psychedelic Era (released on Elektra/Sire), the Pebbles series (AIP/Mastercharge/BFD/ESD), and the Back from the Grave series (Crypt).

My first thought when he mentioned that particular span of years, however, was the Beatles. How did he feel about them? “I do actually like all of the Beatles records,” he says. “I don’t think there are any bad ones. But when I was in that period of time, I wouldn’t have even listened to Abbey Road; The White Album was maybe on the cusp; I probably would have listened to Sgt. Pepper’s but I would have been like, ‘This is a bit too psychedelic.’ That’s where my head was at. I was like, ‘Help is the pinnacle of songwriting in the Beatles catalog.’ Teenagers are weird,” he comments, smiling.

So, when Mackenzie began making music with King Gizzard, his self-indoctrination in garage rock naturally nurtured the young beast of a band. Of course, by their fourth studio LP, the psychedelic, folky Oddments, they started taking a bit of a detour. “As we evolved, I think we wanted to try and pick apart and understand other ways of making music,” says Mackenzie. “How do you make a record that still feels like a whole, still feels like a universe in itself, but doesn’t sound like anything that you’ve done before? And that’s always kind of been the MO of making records with Gizz. I mean … that’s my life story at this point.”

YouTube It

Performing “Astroturf” from their 2022 album, Changes, King Gizzard conjures a blend of smooth jazz, prog, and nothing but strange, whimsical, waves of limitless creative energy.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)