“Did you grow up Unitarian?” Annie Clark asks me. We’re sitting in a control room at Electric Lady Studios in New York’s West Village, and I’ve just explained my personal belief system to her, to see if Clark, aka St. Vincent, might relate and return the favor. After all, does she not possess a kind of sainthood worth inquiring about?

St. Vincent - Flea (Official Audio)

But the sincere curiosity I sense in her question is charming. It hasn’t been mentioned in our conversation yet that she was partly raised Unitarian Universalist (the other part, Catholic), and it’s as if she’s innocently excited that there might exist a friendly connection between her and I, the sunny, “nonchalant” journalist who’s doing my best to hide a fair level of enthusiastic fandom and admiration for her.

“I was raised Catholic, actually,” I reply.

“I love the saints,” says Clark. “Gimme a Caravaggio any day. And Mary as a figure; I’ve always….” she trails off, wistfully. “I’ll always love Mary.” (This adds up, as under her long black coat, she’s wearing an oversized t-shirt with an icon of the Virgin Mary on it, where the religious figure also happens to be depicted as a Black woman.)

Of course, St. Vincent—who took her stage moniker from a Nick Cave lyric—isn’t meeting me at Electric Lady to muse on spirituality. We’re there to talk about her latest release, All Born Screaming—her eighth studio full-length. It also happens to be her first entirely self-produced record, and with this new 10-track collection, Clark feels a sense of celebration about her growth as an artist over the course of her career.

All Born Screaming, which grew out of multiple hours-long solo jam sessions full of “bleeps and bloops,” is St. Vincent’s first entirely self-produced record.

“I’m very lucky to be in a position where more people care about what I do now than what I did on my first record,” she shares. “Like, thank god that I didn’t just have one that people liked, and then fell off the map. I got to grow as an artist and carve out whatever little lane I have in the world by getting to follow the muse and make music that lights me up, that I believe in.”

I would agree that All Born Screaming is a rather shiny jewel to be added to St. Vincent’s experimental, electroacoustic, art-rock crown. It’s ethereal and supernatural, which is to be expected from Clark, but this time, there’s something a little different in the air. The opening, “Hell Is Near,” conjures an illusion of billowing and enveloping fog, swallowing up the audience à la Stephen King. Her floating, sneakily adept vocal at times echoes that of her good friend Carrie Brownstein on Sleater-Kinney’s release from earlier this year, Little Rope, creaking and reaching with pangs of metaphysical desperation.

“Thank god that I didn’t just have one [album] that people liked, and then fell off the map. I got to grow as an artist and carve out whatever little lane I have in the world.”

The album’s first two singles, “Broken Man” and “Flea,” are framed by methodically chugging bass lines that nudge ominously at the edges of your shadowy mental recesses. (On “Flea,” Dave Grohl guested on drums.) “It was pouring, like a movie / Every stranger looked like they knew me,” she sings on “The Power’s Out,” calling David Bowie’s “Five Years,” the 6/8 opening track on Ziggy Stardust, to mind. Towards the close of the record, “Sweetest Fruit” and “So Many Planets” proudly, shamelessly, groove.

And guitar? It enters with an eerie George Harrison-esque jangle on the second verse of “Hell Is Near,” and, throughout the rest of the record, guides with punchy, distorted leads, accents, and welcome interjections. Clark, who was named the 26th greatest guitarist of all time by Rolling Stone in 2023, has rarely imprinted much of an athletic stamp on her music, in terms of shredding—which she’s shown she can do, but, almost as an aside to her more popular artistic definition. Instead, she moves the instrument in and out of her compositions in streaks of indigo, threading it like dendritic capillaries through a Junoesque, avant-psychedelic, gas-giant planet of sound.

Clark was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and moved to Dallas, Texas, with her family when she was 7. There, she developed a tight-knit group of friends with whom she’s still close with today.

Photo by Alex Da Corte

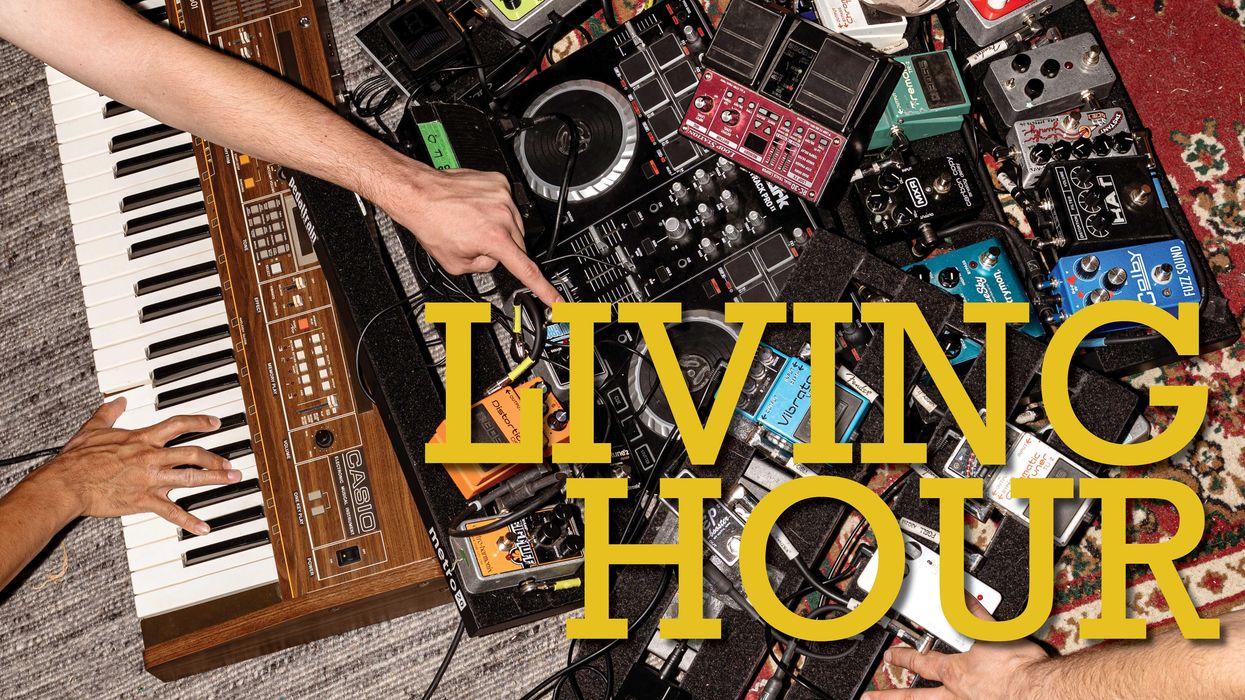

St. Vincent has an unshakeable confidence about her, in both her physical presence and creative exploits. She explains how, in her solo production pioneering for the making of All Born Screaming, she built out her home studio, got a Neve console, set up her modular synths and analog drum machines, and “finally figured out how to MIDI clock everything in time, which was its own hellscape.

“But then, [it was] playing with electricity,” Clark continues, “because electricity through analog circuitry.... I think it has a soul. Ultimately, you’re harnessing chaos. You’re like a god of lightning or something, you know?” she laughs.

“I would just jam for hours, making kind of post-industrial music, and then I would go back through and listen and go, ‘Ooh, well, this is a three-hour jam of bleeps and bloops. But, these four seconds are something so cool that I want to build a whole song around them,” she shares, then vocalizes some of the melodies in “Big Time Nothing,” “Broken Man,” and “Sweetest Fruit.”

Elaborating on her production approaches, she says, “Psychically, I’m obsessed with people like Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry or J Dilla, where all of the effects are tactile. What I find exciting is making big decisions and then printing things, or the sound of something. ’Cause then it’s like you’re building a house on rock rather than sand,” she shares, referring to recording effects with the raw audio signal, as opposed to applying them after the signal is tracked, or in post-production. After further reflection, she concludes, “I think producing the album myself was like managing various egos, but all of the egos were in my own brain.”

We’ve been chatting for about half an hour, and St. Vincent mentions that she brought some snacks, if I want any. (I politely decline, as I’d rather not hear chewing on the recording of the interview when I listen back.) When I presume that she must have a strong sense of self-actualization at this point in her career, she gently counters, “But, I think, you don’t get the confidence without walking through some fire of self-doubt. As I grow more proficient, have more expertise, or get better at my instrument in various ways, music as a whole is more mysterious, mystical, and otherworldly than ever,” she adds. “So, understanding that feels more like it’s receding in a beautiful way, or opening in a beautiful way, while … ‘Okay, great, I know how to compress this better.’”

“What album of yours, excluding All Born Screaming, do you feel the most proud of?”

“Because I’m putting a set list together [for the All Born Screaming tour], I went back and listened to Strange Mercy. There are moments on that, tracks like ‘Surgeon,’ that I’m like, ‘Fuck yeah! That rips! I had no idea!’” she exclaims. “And that’s not always the case. You go back to certain songs, and you’re like, ‘Uh, I’m not sure I executed the vision here, or if this was … a good vision to have.’ But yeah, because I was so broken and bereft at that particular period of life.... I think you can hear it.”

St. Vincent's Gear

This shot was taken a year before the release of St. Vincent’s 2015 self-titled album, where she wore a hairstyle similar to this one on the cover. It was also four years before her signature Ernie Ball Music Man guitar debuted.

Photo by Tim Bugbee/tinnitus photography

Guitars

- Ernie Ball St. Vincent signature models

Amps

- Marshall 1974X

- Roland JC-40

Strings & Picks

- Ernie Ball Regular Slinky (.010–.046)

- Ernie Ball Nylon Light

Effects

- Rig controlled by RJM Mastermind and Gizmo loop switchers

- Hologram Chroma Console

- Empress Echosystem

- Universal Audio Golden Reverberator

- Electro-Harmonix Small Clone

- Malekko Diabilik

- EarthQuaker Rainbow Machine

- Boss VB-2 Vibrato

- JHS Colour Box

- Fulltone Distortion Pro

- Ibanez Modulation Delay II

- Boss SY-200

- ZVEX Fat Fuzz Factory

- Chase Bliss Mood

- Chase Bliss Habit

“You told The Guardian recently, ‘Artists and songwriters are in some way writing about the same thing over and over again: sex, death, love.’ Do you have any other thoughts on that?” I ask.

“Oh, did I say that? Sure!” she chimes, laughing. “Maybe I did!”

“My favorite art has always been stuff that channels the stream-of-consciousness mode of thinking. Do you know Mirror by Andrei Tarkovsky?”

“No, I haven’t … read it?”

“Oh, it’s a film.”

“Seen it!” she amends, smiling. “But, understanding that sort of time-scape dreamscape multiverse…. I feel you.”

“I think Yes’s Close to the Edge is something like that; it’s one of my top 10 favorite albums.”

“I love Yes. Close to the Edge is one of my favorite records as well,” she says, and sings the melody to “II. Total Mass Retain” from the 18-minute-long title track. “And Chris Squire’s bass tone is perfect. It’s perfection on that record.”

“Absolutely! But I admit, I’m really just into early-’70s Yes.”

“Oh, 100 percent. ‘Owner of a Lonely Heart’ just reminds me of … being at the Texas state fair and my friend giving a hand job on a Ferris wheel to a carnie.”

On tour for 2018’s MASSEDUCTION, Clark plays a model of her EBMM signature with a leopard-print pickguard.

Photo by Tim Bugbee/tinnitus photography

While Clark shares that at certain points in her life, she has delved into practices like transcendental meditation, she says that today, the non-musical habits that best cultivate her creativity come down to activities as simple as working out, “so I don’t feel crazy,” and doing chores. “Oh, that’s so depressing,” she laughs.

And, while she doesn’t subscribe to any kind of organized religion, St. Vincent is entranced with a kind of spirituality behind making music. “I find music to be incredibly mystical, and that songs become prophecies,” she reflects. “Artists have, in the best-case scenario, an antenna up that makes them a kind of psychic mirror to the society that they live in, right? Almost like a weathervane.

“There have been times that I have written something that in a way prepared me for, or, predicted something that I was about to go through, in very specific, very witchy ways,” she continues. “I’m not a person of like, faith faith, but I have known certain things in ways that are not rationally explicable.”

“I think producing the album myself was like managing various egos, but all of the egos were in my own brain.”

Musicians have a common language of creativity, in that for most, inspiration tends to emerge unpredictably, out of the ether, or perhaps as the result of neurons firing haphazardly. But they do seem to each have an individual way of keeping track of their ideas, whether that involves writing them down or committing them to memory; usually, it’s a balance between the two. “I’ve had the title ‘All Born Screaming’ since I was 22,” says Clark. “I knew that I was going to use it at some point, but I don’t think I was worthy of explaining the complexity or talking about it until this record.

“I don’t know how records get finished,” she elaborates. “But I trust the process enough to know that, if you just put in the hours and stick with it, eventually the big picture will reveal itself to you. I describe the process as making perfect little puzzle pieces—making sure every edge is perfect and ornately drawn, and I don’t know what the big picture is until I’ve finished every single puzzle piece. And that’s when I go, ‘Oh, this is what this is [laughs]. Nobody told me!’”

While Clark’s guitar playing got off to a typical start—the first couple parts she learned were the opening chords to Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and the iconic riff from Jethro Tull’s “Aqualung”—her evolution as a player has made her increasingly savvy at envelope-pushing. Even on her 2007 debut album Marry Me, a singer-songwriter project at its core, the songs “Now, Now” and “Your Lips Are Red” lean toward the progressive territory she’s mined deeper and deeper since. It would be fair to call her soloing and style of arranging daring and subversive; she bends sound and songform as she sees fit.

“Artists have, in the best-case scenario, an antenna up that makes them a kind of psychic mirror to the society that they live in.”

By 2011’s Strange Mercy, whose collection includes the distinctively electroacoustic-yet-guitar-enforced tunes “Cruel” and “Surgeon”—which, as previously asserted, “rips!”—Clark’s guitar is cloaked in fuzz and couched in ambience and synthesizers. And, in the 13 years since, it’s pretty much stayed loyal to that description. The oddest thing, however, is this duality: That shrouding somewhat precipitates her guitar’s erasure from the foreground of the listener’s earscape, while yet maintaining its stitching throughout the songs themselves. I’ve listened to plenty of her discography, all the while forgetting it right as it’s there. Perhaps, the synths are the furniture, and the guitar is but a centered lamp, unifying the room’s elements within the same bath of light? But, personally, I have not been able to answer the question “How?”

Regardless, St. Vincent couldn’t care less about her image or sound as a “guitarist.” If she has ever made any kind of effort to “prove” herself on the instrument, I haven’t come across a record of it. An educated ear will recognize her august aptitude in her avant-garde playing style, and she has left it at that. In my eyes, this makes her an actual hero in an industry saturated with overcompetition and machismo.

“Sound has incredible meaning,” she summarizes, and the end of our conversation. “It led me to songs, and when you trust that you just will follow the things that will light you up inside, then you’ll be okay.”

YouTube It

On Later… with Jools Holland, St. Vincent rocks her Ernie Ball Music Man signature guitar in “glam tuning,” where all strings are tuned to the same pitch, enabling her to create a synthesizer-like effect with the help of a slide.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)