No style of amp is so definitively a part of a musical genre and culture as high-gain amplifiers. In the modern amp market, there’s a wide range of amps that can achieve a heavy tone, from hulking stacks to lunchbox heads, but their objective unites them. High-gain amps are a cornerstone of electric guitar, and their aggression is heard in every style of music under the sun.

The debate about where high-gain started rages on, but there’s a strong consensus that Tony Iommi and Black Sabbath had more than a little to do with it.

“The first record that really had an impact on me, with regards to that aspect of tone, was Sabbath Bloody Sabbath,” says Sweetwater hard content creator and former Grim Reaper guitarist Nick Bowcott. “It was a brutal sounding record. Iommi was so ahead of his game.”

Keep in mind that there were no high-gain amps when Iommi got his start. Instead, Bowcott explains, “He was doing his thing with a modded Dallas Rangemaster (treble booster) and running into a (Laney) Supergroup while often tuning down to C#. That’s how far ahead of the curve he was.”

Iommi’s tone and Sabbath’s influence were so dramatic that guitarists worldwide adopted it while honing it into a faster, more streamlined style. It was the beginning of heavy metal, and even the world’s biggest rockers claim it’s still unmatched. “Rob Zombie said, ‘The reason there aren't any more good heavy metal riffs today is because Iommi wrote them all,’” Bowcott adds. “It reminds you of how brilliant those songs are.”

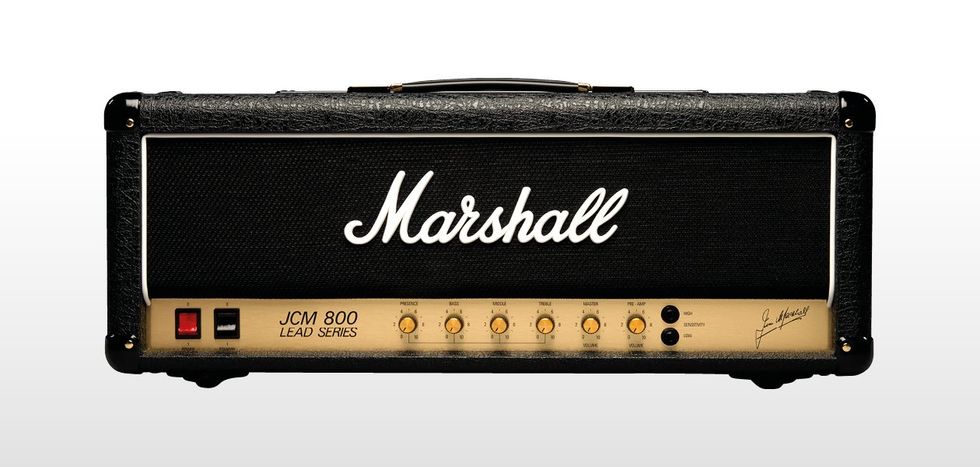

The Marshall JCM800

Introduced in 1981, the Marshall JCM800 series kicked open the doors to the high-gain amp market.

Like Iommi’s Laneys, the tube amplifiers of the time didn’t offer the quick response, tight low end, and increased distortion those players required. The closest thing on the market was Marshall’s 1959 Super Lead, aka the plexi. While definitely distorted, these amps only gave up their saturated tones when played much too loud for most performances.

Guitarists begged for an amp that gave them the tones of Van Halen, Randy Rhoads, and the New Wave of British Heavy Metal, while still being something they could use. Over in England, Jim Marshall responded. In 1981, he released one of the most iconic electric guitar amplifiers of all time, the master-volume-equipped Marshall JCM800 2203.

“To me, the (JCM)800 is a foundational piece with regard to high gain. They owned the ’80s.” —Nick Bowcott

For the first time, the famous Marshall kerrang could be had at gig-appropriate volumes. The amp was a hit, and the JCM800 quickly laid the foundation for what would come. “To me, the 800 is a foundational piece with regard to high gain,” remarks Bowcott. “They owned the ’80s.”

The Mesa Engineering Mark Series

The first Boogies were created when Mesa’s Randall Smith “boosted the daylights out of a little (Fender) Princeton.”

However, Marshall wasn’t the only one pushing overdrive into the modern era. Randall Smith and Mesa Engineering’s first amps—hot-rodded Fender-style combos which Smith called “Boogies”—also marked the transition between vintage and modern with a high-gain voice of their own.

“Early on, I boosted the daylights out of a little [Fender] Princeton,” Smith notes. “It was 80 times the gain of the normal amp! It had this amazing crunch. Power chords and single-note riffs had that vocal, singing thing that made Carlos (Santana) so famous. You could go from the biggest, most amazing Fender clean sound to this level of distortion that nobody had ever heard before.”

Those first Boogies launched one of the most respected names in guitar amplification. Now known as the Mark I, Smith’s amps were soon a favorite of plenty of well-known guitarists.

The Boogie has had multiple variations and feature sets over the years. Each one was given a numeral to differentiate its designs, and the Mark II, with its tighter, more aggressive tone, is where the heavy metal world took notice.

One band, in particular, would launch themselves and the amps to incredible heights after stopping by Smith’s shop in the 1980s.

“Metallica, I remember them coming up,” laughs Smith. “They were young guys. They came up to the factory and grabbed some IIC+s. That was it. That was what they were looking for sonically. They said, ‘Okay, this is what we’ve been hearing in our heads.’”

Smith never considered his Boogie to be a heavy metal guitar amplifier,, but the enormous Mark IIC+-fueled success of Ride the Lightning and Master of Puppets changed that forever.The Amp Modding Craze

Together, the JCM800 and Mesa’s Mark series kicked off a new era in guitar amplification. But, as is always the case, players still wanted more. Many players even modified their amps in search of new, heavier tones.

Before long, the amp-modding community had grown into its own industry with famed amp techs such as José Arredondo, Lee Jackson, and César Díaz squeezing the most tone and gain from the circuits as possible. Those modded amps were the go-to high-gain rigs for everyone from Steve Vai and Paul Gilbert to Alice In Chains’ Jerry Cantrell.

The modification game became so popular, and the modders so well respected, that many began producing their own amp designs. Brands like Bogner, Friedman, and Rivera are just a few that owe a lot of their early success to the mod craze. Even Mike Soldano got in on it.

“I did Marshall mods just like all those other guys,” he admits. “As I started gaining notoriety around L.A., people would bring me their Marshalls and say, ‘Hey, can you make my Marshall sound like this?’”

The Soldano SLO-100

Mike Soldano says he built his first high-gain amp for himself, but soon learned that other players wanted one too.

Soldano’s notoriety was well-earned. As the father of the Soldano Super Lead Overdrive (SLO) 100, many credit him for starting the modern high-end, high-gain tube-amp market.

As a young guitarist, he had faced the same gain-to-volume dilemma that plagued all aspiring rockers of the time. An early adopter of Mesa’s Boogie amps, he thought he had solved the issue, but while the Boogie had a high level of gain, it wasn’t a “high-gain amp.” Unsatisfied with the Mesa and wanting to avoid wrestling with a non-master volume Marshall, he built his own.

“I already knew what I wanted my guitar to sound like,” he says. “I heard it on records, but I knew they were getting that with post-effects and using plexis and big, giant rooms with the volume cranked to 11. I was determined to create an amp that would give me that sound at any volume, at any time, in any place.

“I got a bunch of old radio manuals from the ’40s and ’50s, and every night when I’d come home from work, I’d sit in my room and tinker around, build circuits, and try different things out.”

Soldano was excited about his new creation, but it was other guitarists’ reactions to the amp that told him he was onto something special.

“In order to crank the thing up, I needed to take it down to my friend’s rehearsal space. Every time I did, everybody in the place would start flocking to the room, and they’d be like, ‘What are you guys playing in there? I want to try it!’ I realized then that that sound wasn’t just the sound I wanted. There were other people who wanted it, too.”

“I already knew what I wanted my guitar to sound like…. I was determined to create an amp that would give me that sound at any volume, at any time, in any place.” —Mike Soldano

It took a while, but eventually, Soldano’s new amp started turning the heads of all the right people. “When I first got to L.A., I met Howard Leese,” he remembers. “The next morning, I shot out to meet him at Rumbo Recorders and took my amp with me. He plugs it in, plays about two notes, and he’s like, ‘This is awesome, I'm buying this.’ Then, this guy Tony managed to get an amp in front of Steve Lukather, and Steve went nuts for the thing. Then, I was checking my message machine one day, and there were calls from Lou Reed, from Vivian Campbell, and from Michael Landau. They all were asking about that SLO!”

If the JCM800 started high-gain amps, the SLO-100 was the first tube amp designed for the job. It completely changed the amp industry, and, like Leo Fender’s Telecaster, it remains an industry standard that's largely unchanged today.

The German High-Gain Explosion

Inspired by the SLO’s searing gain, sustain, and versatile volume control, manufacturers began cranking up their amps’ performance worldwide. Builders were finally delivering all the gain and control players wanted.

German makers like ENGL, Diezel, Hughes & Kettner, and L.A.-based Bogner made names for themselves with legendary high-gain heads like their Savage, VH4, TRIAMP, and Uberschall. For European metal guitarists, this was the dawn of a new era.

“The ENGL Savage was my main live amplifier for maybe seven years,” says Haunted guitarist, YouTube personality, and Solar Guitars owner Ola Englund. “Not too many other brands at that time could give you this insanely tight, modern metal sound without using a boost. You just hook up your guitar, and it sounds incredible.”The Mesa Rectifier Series

“The Dual Rectifier just completely proliferated all of the grunge years,” says Mike Soldano.

Between the Marshalls, Mesas, a flood of modded amps, and the amps coming out of Germany, the late ’80s and 1990s had a lot of high-gain to offer. Still, a new amp from a familiar face defined the next couple of decades.

“The (Mesa) Rectifier was the one in the ’90s,” Bowcott says, point blank. “The ’80s were the JCM800, and the ’90s were the Rectifiers.”

“The Dual Rectifier just completely proliferated all of the grunge years,” echoes Soldano. “There wasn’t a band out there that wasn’t playing a Rectifier.”

“We had no expectation that the Rectifiers would end up being so popular.” —Randall Smith

Today, Randall Smith’s Mesa Rectifiers are definitive high-gain amps. Everyone from Metallica and Korn to Soundgarden and Cannibal Corpse uses them to create the heaviest tones in rock history. So it’s surprising they were designed by someone more Santana than Sepultura. According to Smith, he was as surprised as anyone.

“We had no expectation that the Rectifiers would end up being so popular,” he said. “It was to the point that we had to fight that image. Players are like, ‘Mesa, those are the high-gain metal guys. I’m not interested in that.’ But it was only one product! (Laughs)”

The Peavey 5150 And Beyond

The Peavey 6505 and EVH 5150 are both descendants of the original Peavey 5150 designed by Eddie Van Halen and amp designer James Brown.

While Mesa’s Rectifiers had no equal in terms of popularity, one amp did give it a run for its money in impact and aggression: the Peavey 5150. Created by amp designer James Brown and Eddie Van Halen—who had been playing SLO-100s—the 5150 quickly transcended classic-rock heroics and laid the foundation for a new breed of extreme high-gain tone.

Machine Head’s Burn My Eyes was arguably the first release to put the amp on the metal map, while producer/engineer Andy Sneap’s legendary use on countless records cemented it in place. Bands like In Flames, Killswitch Engage, and Arch Enemy also used the amps to great effect.

“The 5150 was probably the most aggressive amplifier out there,” says Englund. “I remember it was either the 5150 or the Rectifier, (those were) the ’90s choices right there. If you played in a serious metal band, it’s one of these.”

Like the Rectifier, the 5150 has seen multiple tweaks and changes since its inception. The most notable came when Eddie took his 5150 trademark to Fender to launch EVH and the 5150 III amp line. Not wanting to drop one of the most popular high-gain amps ever, Peavey gave theirs a facelift and renamed it the 6505. The world lost a hero when Eddie passed away in 2020, but he left us with two amp lines that will go down in high-gain history.

Solid-State High Gain and Dimebag Darrell

The ’90s and 2000s were all about high-gain tube heads. But a handful of solid-state and hybrid amps also drove some of the era’s most intense music. The most famous of these amps was the Marshall Valvestate 8100. While many players denounced its cold, toothy voice, Bowcott says others built a career around it.

“Marshall came out with Valvestate in the early ’90s, and people like (Prong guitarist and singer) Tommy Victor adopted that amp. It was his sound on ‘Snap Your Fingers, Snap Your Neck.’”

Victor wasn’t the only one using the 8100; it’s also the sound of Static-X's Wisconsin Death Trip and, reportedly, shaped the sound of early Meshuggah. No other 8100 player, however, is credited with having the influence and savagery of Death’s Chuck Schuldiner. Plugging into his 8100, he’s widely regarded as creating death metal.

Of course, there was one other high-gain hero who more than deserves a mention when it comes to ’90s solid-state. Pantera’s Dimebag Darrell and his Randall RG100 and Century 200 amps sounded so heavy, singular, and next-level that few have even tried to cop his sound.

“Dimebag had the most distinctive metal tone, and I don’t think anyone has managed to break that,” comments Englund. “It was his and no one else’s. He would just overdrive it to hell and back and add all these doublers and flight flangers and stuff. That was a solid-state tone right there.”

The Rise of Digital Modeling

The legacy of the Line 6 Pod lives on, elevated to stages everywhere, in the Helix.

How guitarists get their high-gain tones has changed drastically over the years, and that’s never been more true than in the last couple of decades. Instead of walls of amps and 4x12 cabinets, these days, we get remarkably similar sounds from compact digital rack and floor processors. Evolving from the original Line 6 POD, digital modeling now defines this era of guitar.

Initially relegated to practice tools for home use, starting in the late 2000s, bands like Periphery and Animals As Leaders have increasingly embraced modeling units like the Fractal AXE-FX, the Kemper Profiler, the Neural QuadCortex, and Line 6’s flagship Helix. The bands’ pristine tones, impressive musicianship, and pummeling riffs opened the floodgates of high-gain for a new generation. They’ve established modeling as a legitimate tone tool for professionals and even won over old-school rockers like Bowcott. “There’s some amazing stuff out there,” he says. “You can argue that there’s never been a better time to be a guitar player, apart from maybe decision paralysis.”

The impact of digital amp modeling can’t be overstated. Whether a physical unit or the countless inexpensive software amp sims, they all sound realistic, respond remarkably well, and open a world of routing and control options. They’re so prevalent that many younger guitarists have never even owned a tube amp.

Tube Amps and Impulse Responses

The Revv G20 is one of a growing number of modern lunchbox-style heads with IR capabilities combining portability and high-gain tone.

So, will digital modeling actually kill high-gain amplifiers? The consensus is probably not, but tube amps do have to evolve. The answer may lie in impulse responses (IRs).

Impulse responses are digital snapshots of real speaker cabinets and microphones loaded onto a modeler or computer. They let you hear a well-recorded cab without plugging into an actual speaker.

More and more brands are adding IR capabilities to smaller, lunchbox-style tube amps. Heads like the Revv G20 and ENGL Ironball Special Edition are pioneering this approach and striking the perfect balance of tradition and convenience. Randall Smith is a fan, and Soldano even joined the party with his Astro-20.

“I think it’s a great evolutionary step. That’s ultimate if you ask me,” says Smith. “The important thing is that you have your tube amp. You’re not sacrificing that in order to get the virtues of digital and modeling.”

Soldano echoes Smith’s enthusiasm, saying, “I think for home recording, it’s going to completely take over. It’s a perfect recording amp. You can set this thing on your desktop. You don’t even have to plug in a speaker cabinet. You can run it straight into your digital mixing world, and you can bring up these different IRs. You can do amazing stuff without even a single dB of sound in the room.”

Long Live High-Gain Tube Amps

Hybrid tube designs are helping ensure a bright future for high-gain tube amps. Still, Soldano, Smith, Englund, and Bowcott agree that tube rigs weren’t going anywhere anyway.

“On any Friday night, in any bar in any town, you’re still going to see some guy up there or some gal with a 50-watt half stack rocking it out,” says Soldano.

“The metal community, they still want moving air,” adds Englund. “That's something that can’t be modeled. You can’t explain it, but when you stand in front of an amplifier, it’s so easy to justify.”

Bowcott also agrees but says the experience extends beyond plugging in. “I remember, back in the day, going to see Diamond Head and Judas Priest. They had that huge wall (of amps) that, before they played a note, you’re like, ‘This is going to be cool!’ There was something visually visceral.”

High-gain tone has taken many forms over the decades. From Iommi’s influence to the tech-death insanity of bands like Archspire, it’s forever part of the electric guitar lexicon. As it evolves, so do the tools we use to achieve it.

Nothing will replace the physical interaction of a cranked tube head. At the same time, nothing today matches the convenience and possibilities of digital modeling. Then again, maybe the hybrid approach is the future. Whatever's next for our favorite heavy sounds, there are still plenty of legendary builders, technological innovators, and boundary-pushing players working hard to ensure high-gain guitar tone is here to stay.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)