Let me take you back, good people, to a time when The Ed Sullivan Show was featuring rock ’n’ roll bands beamed into homes via brand-new color televisions. This was when the U.S.A. was experiencing a prosperous, post-WWII era filled with ideas of space exploration, jukeboxes packed with vinyl records, and muscle cars cruising the highways. For most in the States, the early 1960s was a great time to grow up and an even better time to want to play electric guitar. It was the era that birthed garage bands. Demand for electric guitars boomed, and guitars were being designed as original models rather than copies of copies. I could write several volumes about guitar design variations, but for this article let’s examine a curious chapter of electric guitar production: the age of fully transistorized Japanese electrics, from 1964 to 1966.

For historical perspective, let’s look at the dawn of solid-state technology. Back in 1947, Bell Laboratories developed an alternative to the costly and problematic vacuum tubes that powered most electronic devices. This transistor technology slowly found its way into consumer products, but was truly embraced in portable radio formats. Before this time many radios were huge and bulky, often positioned as the centerpieces of living rooms. Transistors made it possible to seriously downsize radios so you could carry a pocket-sized one, cranking out the latest Beatles tunes. It may not seem like much of an innovation compared to our palm-sized smart phones, but this new form of technology appealed to the young baby-boom generation. It allowed for more expedient ways to get news and music, all wrapped up in the novelty of transistor radio design. These little radios appeared concurrently with electric guitars in all sorts of pop-culture references on TV, in movies, and in print publications.

Transistor technology was available to many Americans in the 1950s, although the cost of such devices was often expensive. But a few visionary Japanese engineers were visiting the U.S., including Masaru Ibuka, with their eyes on the market. He was the co-founder of Sony, and his fledgling company began making transistorized electronic equipment under license from AT&T. By the early 1960s, Japan had become a major player in transistor radio production, with Sony competing with other Japanese companies such as Toshiba and Sharp. This manufacturing boom was concurrent with the electric-guitar boom and the explosion of popular guitar music. The planets aligned, and soon the technology of both guitars and radios morphed into an interesting combination: the “amp-in-guitar” concept.

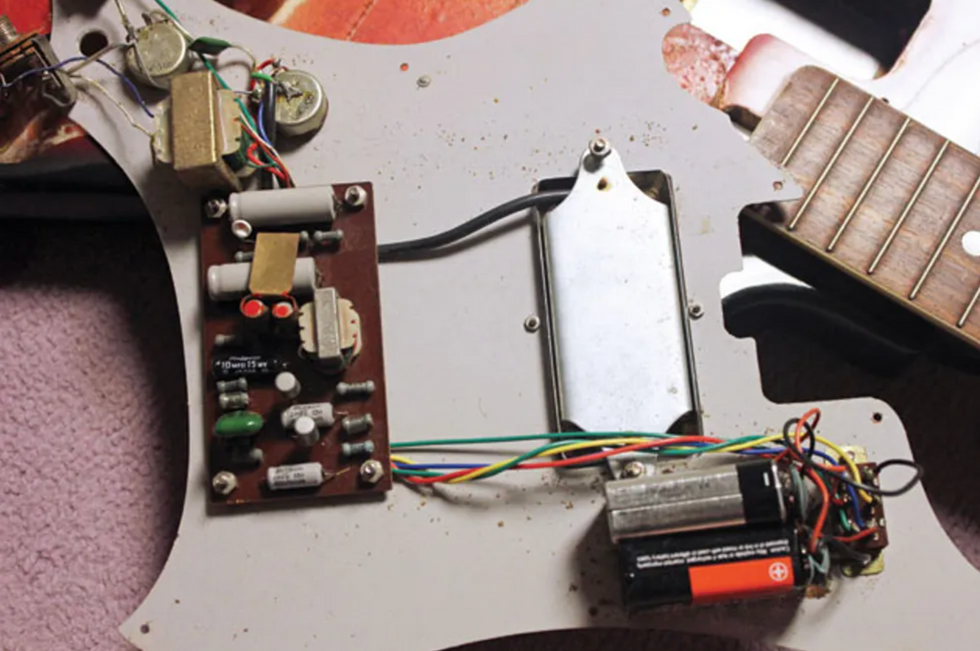

Image 1: Attaching a simple, radio-like circuit board platform to a pickup begat the concept of onboard amplification.

One of the earliest examples of these transistor amplifiers appeared on the German-made Hofner “Bat” guitar of 1960—the year it debuted at a European trade show. The Hofner Bat, known as the Fledermaus in the company’s catalog, was produced in very low numbers and is now arguably the rarest of all Hofner electric guitars. It featured a pretty radical angular-but-symmetrical design that incorporated a transistorized amplifier and speaker inside the guitar’s body. Also appearing in the early ’60s were the Italian-made Wandre Bikini Avanti 1, which featured a detachable amp that connected to the lower bout of the guitar, and the Meazzi-branded Transonic, which had a fully integrated amp and speaker in its body.

Image 2: Wandre’s Bikini models sported a detachable amp that connected to the guitar’s lower bout.

Photo by Robert Patrick

Even though these models pre-dated the Japanese models with onboard amps, the Italian guitars were also hard to find in the U.S. and were very expensive. The Wandre Avanti 1 was imported by the Maurice Lipsky Music Company in the early ’60s and priced at an astounding $395.

Image 3: Italian guitars like the Meazzi Transonic arrived on these shores as pricey imports.

But the advertisement for the Avanti 1 read, “No Wires, No Outlet Worries, Plays Anywhere.” Those taglines really reflect the sense of freedom and mobility that transistor technology offered the guitar-playing community. Hey, take your Wandre Bikini to the beach party!

Teisco Silvertone TRG 1 Amp-in-Guitar Vintage Japan

Okay, it ain’t a Marshall combo, but this Teisco TRG-1’s onboard amp does have its own character, and after the guitar’s plugged into a stand-alone amp at the 2:00 mark, it’s obvious that the 3" speaker accurately reflects the natural tone of the instrument.

Japanese guitar maker Teisco introduced two transistorized models in 1964: the round-necked TRG-1 and the TRH-1 lap steel. Of course, the true proliferation of the technology was dominated by the Japanese makers of the time, and the Teisco Company led the way when Japan Music Trades magazine featured the newly introduced Teisco TRG-1 in June 1964. Also introduced was a lap steel called the TRH-1.

Image 4: Teisco TRG-1

The “TR” standing for “transistor,” these new models were basically takes on existing guitar designs. The TRG-1 featured a slightly larger Teisco ET-300-style body and one pickup, with the small amplifier mounted under the pickguard where a bridge pickup would otherwise reside.

Image 5: Teisco TRH1

This model had a few different names in its early days, such as TRE-100, TRET-100 (with a tremolo), TRG-1, TRG-1L, and probably a few others. But they were all essentially the same model, offering “new sounds in music.” In 1964 and 1965, Teisco really promoted the amp-in-guitar models in Japan and, here in America, Weiss Musical Instruments was placing advertisements in Music Trades magazine as early as February 1965. Also appearing in 1965 was a Silvertone-branded variation, called the 1487 in Sears literature.

Image 6: Teisco’s ads of the era boasted “new sounds in music” and a decidedly “mod” look.

All of these Teisco-made guitars could be plugged into an amplifier and played like a “normal” guitar, or you could use the internal amplifier powered with 9V batteries that were installed through an access plate on the back of the guitar.

Image 7: Sears’ in-house guitar brand, Silvertone, entered the competition in 1965 with the 1487 model.

All of these Teisco-made guitars could be plugged into an amplifier and played like a “normal” guitar, or you could use the internal amplifier powered with 9V batteries that were installed through an access plate on the back of the guitar.

Image 8: A 3" speaker with 1 watt of power was de rigueur for the self-contained 6-strings of the 1960s.

The batteries fired a tiny transistor amplifier that put out about 1 watt of power through a 3" speaker. You definitely weren’t going to play a house party with this setup, but it was perfect for bedroom jamming and learning songs off the record player.

There were several other Japanese amp-in-guitar models that appeared during 1965, including a super-cool instrument made by the short-lived Shinko Gakki company in the city of Tatsuno. The rarely seen Shinko example was sold in the U.S. through the New York-based Inter-Mark Company, which branded all their guitars as “Cipher” models.

Image 9: This one-pickup Cipher model imported by the Inter-Mark Company originated in Tatsuno, Japan.

The Maier example pictured below was made by another Japanese manufacturer, forgotten by time. After examining the components, this guitar seems to have been produced in the Matsumoto area of Japan. Even the import name of “Maier” is a relative mystery. After pouring through stacks of trade magazines from the era, the only possible clue I’ve found is the R.J. Maier Corp. of Sun Valley, California.

Image 10

They were primarily known as a maker of clarinet and saxophone reeds, but during the guitar boom of the mid-’60s, all sorts of musical instrument companies were importing electric guitars. Either way, the Maier variation follows the familiar blueprint of a single-pickup guitar powering a tiny amp through a 3" speaker.

Image 11

Finally, this two pickup variation, also below, was made at yet another Japanese factory that remains a mystery. I have owned this same model without the internal amp, and the designers simply routed out the regular guitar bodies to accept the transistorized components. But this example features a headphone jack!

The makers of these guitars—a one-pickup model with a Maier-marked headstock and a two-pickup model with a headphone jack—are a mystery today.

There aren’t any records of how many of these amp-in guitars were sold, and I often wonder about the popularity of this format. But by 1966 most all of these guitars had vanished from catalogs, advertisements, and literature. As with many of the Japanese imports, these all-transistor guitars were relegated to closets and pawnshops. Rory Gallagher famously adored his Teisco TRG-1 and recorded with it. But other than that famous connection, the brief history of these guitars has been largely ignored.

Meazzi Supersonic Vintage 60s - Demo

This cousin of the Meazzi Transonic seems to feature a plywood top and has a distinctive-looking pickup with a serviceable, if feedback-prone, amp onboard.

So how do these internal amps sound? Well, they sound like a tiny transistor radio! And for those of you too young for the comparison, imagine a seriously lo-fi sound that’s tinny and raw. Really, these amps were more about portability than sound. Even when direct miked, they sound weak, but—as with all tones—there is a place for this sound in someone’s creative imagination.

Unfortunately, these old amps are almost always in need of repair due to bad capacitors. The values on these capacitors are often odd, but they can be repaired easily enough by almost any good electronics repair tech. I’ve owned eight of these transistorized electric guitars over the years, and all but one needed repair work on the amp circuitry. But when these guitars are fixed up, I love using them. I still take my Teisco TRG-1 to the shore every year. And when my kids were born, you can bet my playing was limited to the 1-watt amps in these guitars as I plucked lullabies in the wee hours of the night. Even today there’s a place for these oddities of ’60s technology and guitar playing!

Frank Meyers is the author of History of Japanese Electric Guitars, published in 2015.

[Updated 3/2/22]

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)