Since the dawn of garage rock, basements and carports across America have played host to untold thousands of high school friends looking to fulfill that insatiable need to form a band. And, of course, it’s never easy, but even when everything clicks, it’s probably safe to say that not many of them wind up getting signed to the genre-defining indie rock label Matador Records on their first try.

“For us, it started purely as three teenagers who were doing it for fun,” gushes Penelope Lowenstein—at 18, the youngest member of the teenaged three-piece Horsegirl, who in the short span of three years have gone from jamming together in their parents’ basements to, this October, opening for the legendary alt-rock outfit Pavement on their much-touted reunion tour. “I don’t know how it usually happens for bands, but it was just this weird moment where suddenly we were on peoples’ radar. Eventually we recorded a bunch of demos, put them on Soundcloud, and sent them to all the labels who had become interested, and that’s how we were connected with Matador.”

It isn’t easy to make good songwriting sound effortless, but this power trio—and they are definitely that—is making it happen.

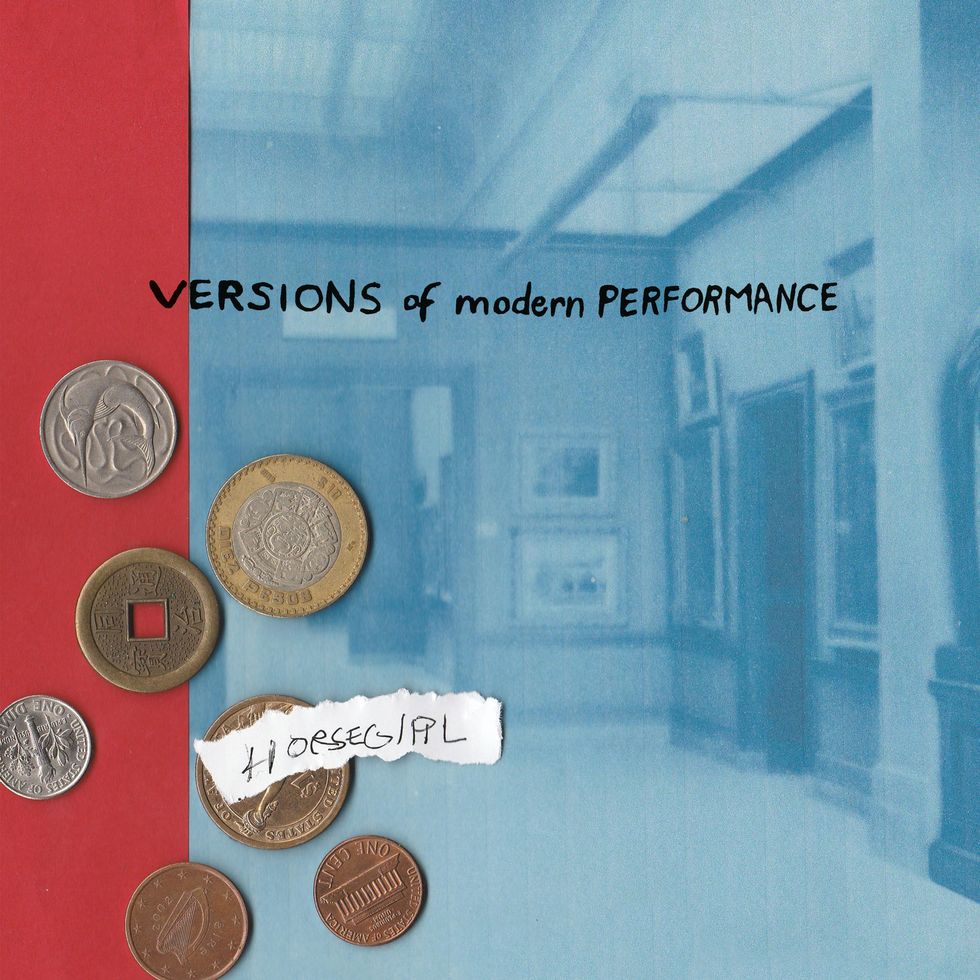

There’s more to the story, but for now here’s the nitty-gritty: Versions of Modern Performance, Horsegirl’s debut album, is 34 minutes of voluminous sonic joy, tracked in its entirety at Steve Albini’s stalwart Electrical Audio and produced by studio vet John Agnello, whose prestigious credits include work with Dinosaur Jr., Sonic Youth, the Dream Syndicate, and Kurt Vile, to name just a few. Lowenstein switches off on guitar, bass, and vocals with Nora Cheng. They met and cemented their friendship while taking part in the School of Rock program in their native Chicago. (Sidenote: They first played together in a cover band that featured, you guessed it, Sonic Youth songs on the setlist). Gigi Reece, Horsegirl’s drummer, joined in early 2019, bringing an instant powerhouse backbeat to the band’s sound, which surges with a psychedelic fervor that conjures tastes of the Velvet Underground and Nico, My Bloody Valentine, Stereolab, and Yo La Tengo—again, to name just a few.

Beautiful Song

“We were brought together by this shared love for the same kind of music,” says Cheng, describing how the resurgent Chicago scene, tough-to-crack but nurturing when it counted, eventually helped propel Horsegirl into the spotlight. They recorded their first single, the cavernous and hauntingly folk-tinged “Ballroom Dance Scene,” with their friends Jack Lickerman and Niko Kapetan (whose own band, Friko, has carved out a distinctive dream-pop niche). Eventually the Chicago Tribune came calling, running a high-profile feature on Horsegirl that sparked a critical buzz. “This was after more and more bands had started popping up that seemed to share similar influences with us, or the same ethos, I guess you could call it,” Cheng observes. “I don’t know exactly how it happened, but it all turned into a very supportive, young community.”

In a sense then, Versions of Modern Performance is as much a reflection of the scene that elevated Horsegirl as it is the band’s full-throated statement of purpose. From the sharp angles and resonant chords of the uptempo opener “Anti-glory” to the layers of sludge and whistling guitars in the mournful “Billy” (loosely inspired, with its E–B–E–B–E–B tuning, by the music of Nick Drake), the album conveys a warm, enveloping analog atmosphere where heavy-leaded psych rock, recombinant proto-punk, wistful indie-pop melodies, and volcanic blooms of guitar feedback all collide in a crucible of spontaneity. Infuse all that with a healthy dose of controlled chaos and the multi-colored picture of what Horsegirl is all about begins to take shape.

Nora Cheng’s Gear

Nora Cheng gets sonic with her Ibanez Roadstar II at the Sinclair in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on August 7, 2022.

Photo by Tim Bugbee/Tinnitus Photography

Guitars

• Ibanez Roadstar II

• Fender Jaguar

Amps

• Vox AC30

• Fender Twin Reverb

Effects

• Ibanez Tube Screamer

• Keeley Electronics Loomer Fuzz/Reverb

Strings and Picks

• Ernie Ball Regular Slinkys (.010–.046)

• Various picks

“We had a very clear idea of how we wanted this record to sound,” Cheng says, referring to the band’s initial sessions with Agnello. “The main thing was to stay away from being too polished. We wanted it to sound like our live set. It just goes with the idea of us being a trio, and wanting to capture that live sense on the record. And it was really helpful to have somebody working with us who understood that.”

“It was hard to keep up on an actual bass, but the Bass VI made it easy for my hands. It was also a huge turning point for us songwriting-wise, because as a guitarist I can only think of it in guitar terms.” —Penelope Lowenstein

Daunted only slightly at first by the magnitude of recording at Electrical Audio (“it was crazy to see Fugazi’s thank-you note taped to the fridge there!” recalls Cheng), the trio quickly took to their surroundings and established a free-flowing collaborative rapport with their producer. “I think John’s philosophy was very much like, ‘If we get a good live energy going between the three of you, then you don’t really have to add very much else,’” Lowenstein recalls. The band set about duplicating their live setup, with Cheng relying on her Ibanez Roadstar II (her dad’s college guitar) running through a Vox AC30 or a Fender Twin, while Lowenstein played her early ’90s Fender Strat Ultra (which once belonged to her dad), often through a Fender Hot Rod Deluxe. Interestingly, both guitarists also use coiled guitar cables from axe to pedalboard—a bit of an old-school move that’s perceived by many players as a midrange tone thickener, due to the cable’s length and high capacitance.

Penelope Lowenstein’s Gear

Penelope Lowenstein plays the Squier Classic Vibe Bass VI that she shares with Cheng. The instrument’s guitar-like playability made it an inspiration for songwriting for the band’s debut album.

Photo by Tim Bugbee/Tinnitus Photography

Guitars

• Early ’90s Fender Stratocaster Ultra

• Fender Jazzmaster

• Squier Classic Vibe Bass VI (also used by Nora Cheng)

Amps

• Fender Hot Rod Deluxe

Effects

• EarthQuaker Westwood Translucent Drive Manipulator

• EarthQuaker Bellows Fuzz Driver

Strings and Picks

• Ernie Ball Regular Slinkys (.010–.046)

• Various picks

For the low end, they switch off on a Squier Classic Vibe Bass VI, which Lowenstein acquired from a friend. “I’m still trying to figure out what it needs amp-wise when we play live,” she admits, “but it was really a solution to being in a trio. It was hard to keep up on an actual bass, but the Bass VI made it easy for my hands. It was also a huge turning point for us songwriting-wise, because as a guitarist I can only think of it in guitar terms, but because it’s not a bass I feel like it lets me write whatever the song needs. Sometimes I’ll do low-end things, and sometimes I’ll almost take a guitar solo on it.”

Naturally, both players have embraced the expressive scope of effects pedals, and distortion in particular. Cheng prefers her Ibanez Tube Screamer for most songs, but on the ironically titled “The Fall of Horsegirl,” the violin bow comes out (shades of Jimmy Page!) and she leans into a Keeley Electronics Loomer fuzz/reverb box. “I got it when I was really big into My Bloody Valentine,” she reveals, “and it has some really cool—I think they’re reverse—reverb sounds. We just cranked a bunch of stuff on it like, ‘Okay, what sounds cool with the bow?’ And it turned into this very big, cathedral-like sound. It’s noisy, but it’s also a bit beautiful. That came from a lot of experimentation.”

“The idea behind interludes is not just to be there for no reason. They’re meant to break apart the album and let you settle after this one and prepare for this next one.” —Nora Cheng

Lowenstein comes back to “Billy,” the album’s closing track. “I’ve basically stolen my dad’s Jazzmaster to play just that one song on tour, because it’s ridiculous to retune like that,” she says. “But I have an EarthQuaker Westwood on it—that’s the sound of my main distortion. I also use a Bellows pedal with it near the end. Whenever we want a crazy Horsegirl ending, I just hit the Bellows and it does the rest.”

Horsegirl’s itch for sonic exploration gets scratched on the album’s three brief interludes: the the cavernous “Bog Bog 1,” the feedback-soaked “Electrolocation 2,”and “The Guitar Is Dead 3,” which features all three band members seated at one piano, plunking out a single mournful chord progression that gets processed through a building wave of echo and delay.

Horsegirl digs into a song from their new record onstage at the Sinclair in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Photo by Tim Bugbee/Tinnitus Photography

“I guess the idea behind interludes is not just to be there for no reason,” Cheng says. “They’re meant to break apart the album and let you settle after this one and prepare for this next one. And something interesting about that was we’d developed interludes just playing them live, so it was something that was maybe natural for us to do anyway.”

The band’s most compelling collective trait is their willingness to explore all these possibilities together, as a unit. “Dirtbag Transformation (Still Dirty),” their latest single, is a beautiful example: Over a Breeders-like groove, Cheng and Lowenstein lay into chords that bend and move between Reece’s loping rhythm with judicious use of the whammy bar. “I play my Strat on that one,” Lowenstein recalls. “That’s the only song we recorded with two guitar parts first, and then we added the bass part. We’ve rearranged it live so Nora plays bass and I play a hybrid of the two guitar parts.” The song also moves between minor- and major-sounding moods, and tails out on a sunny coda where both singers take up the underlying wordless melody in unison.

What makes Versions of Modern Performance such a solid and endlessly accessible debut is how the band managed to harness their freewheeling sense of abandon into the rigid structure that memorable songs demand.

Further on, “World of Pots and Pans,” played in open E, harnesses the band’s psychedelic-punk leanings, as does the epic “Homage to Birdnoculars.” The song is a roiling workout that feels seamlessly drawn, with its simple two-note anchoring guitar melody and the recurring lyric “fall into my wormhole,” sounding inspired by the modern Texas-psych blueprint perfected by bands like the Black Angels. But it would be a mistake to try to pigeonhole Horsegirl’s sound as the sum of any set of perceived influences. What makes Versions of Modern Performance such a solid and endlessly accessible debut is how the band managed to harness their freewheeling sense of abandon into the rigid structure that memorable songs demand. It isn’t easy to make good songwriting sound effortless, but this power trio—and they are definitely that—is making it happen. And together with Agnello at the mixing desk they’ve crafted an album that merits repeated Saturday night listens in—where else?—the nearest basement you can find that’s tricked out for sound and kicked-back listening.

Cheng describes “Beautiful Song,” the album’s oceanic second track, as a vivid snapshot of what the band sought to harness and then release. “That’s how we want people to listen to us,” she says. “We all really enjoy the process of listening to a record all the way through, so it was something that we were thinking about. A record was the goal, from even before we had enough songs to make one. And there’s the typical first song that’s strong and sets the tone for the album, but I think the second song is underrated. I tend to really like second songs, because to me, that’s when we’re in the album.”

Recording at Steve Albini’s famed Electrical Audio studio was initially intimidating, but the trio doubled-down to make a compelling, vibrant live-vibe album that recalls primal Sonic Youth.

“I think this is the hardest we’ve all worked in our lives,” Lowenstein asserts, citing the hurdles Horsegirl had to overcome as a band of teenagers seeking entry into an adult world.

Their journey from the hyper-competitive live venues of Chicago to the hallowed studio spaces of Electrical Audio has been a rollercoaster, but, through it all, friendship and an ever-nurturing sense of community have kept them grounded. “We wrote all these songs while we were living this experience. Throughout high school, we were a live band. It was just what we love to do. And where we are right now feels like a really important thing to share with everyone. It’s very special to us.”

Horsegirl - Full Performance (Live on KEXP)

The band runs through some of the meatier cuts from their new album (as well as the fan fave “Ballroom Dance Scene”). Nora Cheng opens with her Fender Jaguar, tuned to open E, and then switches to her reliable Ibanez Roadstar II, while Penelope Lowenstein holds down the harmonic interplay and lower frequencies on her Squier Bass VI.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.