Thurston Moore is onstage cranking up one of his signature Fender Jazzmasters to a darkened room at Rough Trade East, London's record-shopping mecca. The space is empty except for a sound and camera crew, there to document a slimmed-down trio version of his band—with My Bloody Valentine's Deb Googe on bass and Jem Doulton on drums—in gritty black-and-white for the livestream launch of Moore's new album, By the Fire. With his adopted city on the verge of another lockdown, and his home country in the throes of a bitterly contested presidential election, the stakes couldn't be more dire. But Moore and his mates aren't there just to shake their fists or chew the scenery.

“I'm thinking about fire as this emblematic action," he says, “but this record is not a big angry protest record. It's actually going the other way. I wanted it to be a good energy, as a political move against all the bad energy in the air. I always say putting records out is a political move. There's a responsibility to it, especially if you're past the age of 19 or 20. I'm 62, so I think there's a dignity in that exchange. That's probably not something I was so articulate about or aware of as a younger person, but it's interesting to me now because I see that as something very real. When you put records out, or if you're working in a discipline of creative impulse, and you're creating something to be in the marketplace, that's a bit of a responsibility. So I always see it as very political."

Tracked almost entirely at Total Refreshment Centre, a multi-use art space, and Paul Epworth's the Church Studios, both in London, the sessions for By the Fire concluded just before the pandemic hit, but they capture a band that, after three albums together, is clicking and communicating on a deep and visceral level. “The music I'm bringing into this group is not wholly dissimilar to the music I brought into Sonic Youth through the years," Moore says. “It's just more contemporary, more now. It all comes from the same lineage and the same vocabulary. It's always progressing in a certain way, but it'll always have that similarity, that recognizable factor."

Back in 1981, when Moore co-founded Sonic Youth with Kim Gordon and Lee Ranaldo (with drummer Steve Shelley coming on board in '85), the band was so aggressively underground and anti-establishment that none of them even considered the possibility they'd have a legacy to look back on, let alone the accolades for sparking a transformative New York art-punk movement that still reverberates loudly to this day. That experimental ethos informs the music that Moore brings to his current band, with a couple of key differences: where Sonic Youth was more of a democracy, Moore is now calling the shots. And, on top of that, he has stunt guitar-savant James Sedwards riding shotgun.

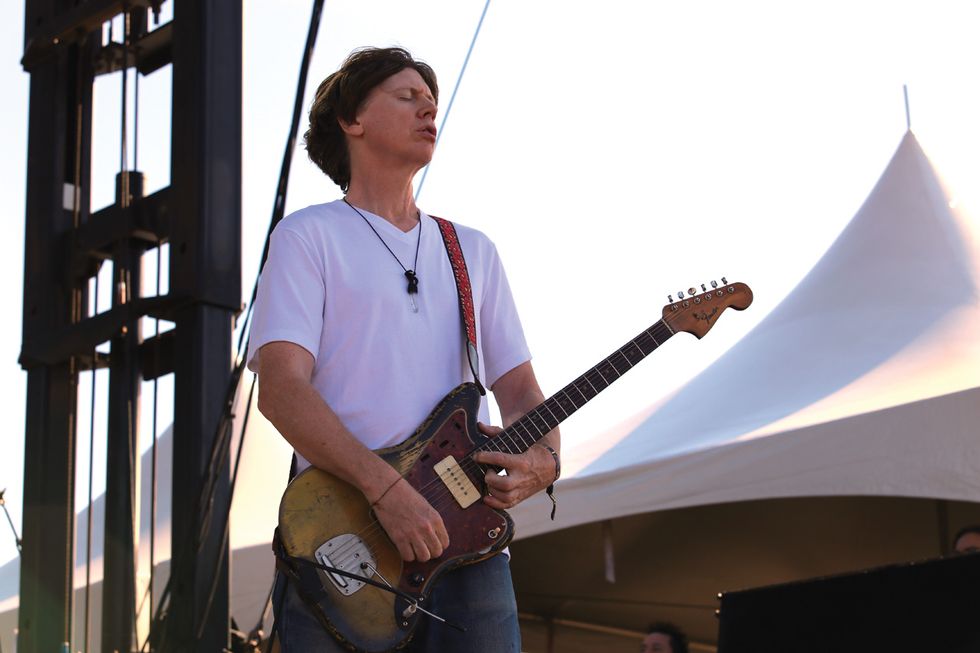

The ex-Sonic Youth co-leader hits the limits of his well-traveled 1959 Jazzmaster's fretboard while playing Riot Fest in 2015. Photo by Chris Kies

“James is such a high-technique guitar player," Moore raves. “I mean, he wakes up and he has guitar for breakfast—he is the guitar, you know?" Brit aficionados of experimental music would concur. Sedwards' own adventures with his mathy noise-rock unit Nøught, which emerged from the same artsy Oxford scene that spawned Radiohead, are the stuff of local legend. The band often draws comparisons to American post-rock acts like Shellac or Slint for their freeform sonic ferocity, while Sedwards' approach to the guitar—always inquisitive and seemingly insatiable—prompted none other than John Peel, during a filming of his 1999 series Sounds of the Suburbs, to praise Sedwards as “the first person who's not been a footballer that I've been jealous of."

Sedwards didn't make the Rough Trade set, but he makes his presence felt on By the Fire. Not surprisingly, Moore recognized their potential as a team—Sedwards also favors a Jazzmaster, and is an avowed Sonic Youth fan—early in their collaboration. “If you listen to the first record we did," The Best Day, released in 2014, “for the title song, I thought it would be cool if James stepped forward and possibly played a lead or something. And what he did was so incredible, I was just like, 'Oh, this guy is a secret weapon, and I'm really under-using him here.' So I've slowly been asking him to shred some leads here and there. I don't want to do it on every piece, but he does come up with something new every time."

On the whole, By the Fire signals something new for Moore and the entire band. The album feels rooted in a spiritual mood of bliss—a good deal of that stemming from the vivid lyrics of poet Radieux Radio in such songs as the opening “Hashish"—but Moore is also painting with a much wider brush than he did on 2017's Rock n Roll Consciousness. Where that album tapped into an accessible thread of avant-garde rock with echoes of the classic canon (Jimi Hendrix, Pink Floyd, Velvet Underground), this one runs with that notion and raises the stakes, from the heavy-booted rawk of Black Sabbath (“Cantaloupe," which pivots on a searingly Iommi-like solo from Sedwards) to the extended noise explorations, reminiscent of Moore's mentor Glenn Branca, that propel the nearly 17-minute “Locomotives." Add the electronic soundscapes of Jon Leidecker (aka Wobbly, also of Negativland) and the further contributions of Steve Shelley (who lends a hard-driving backbeat to the trance epic “Breath"), and By the Fire delivers on multiple promises Moore made to himself when he was mixing the album.

“We do have this intrinsic nature of wanting to communicate," he explains, “and to keep each other safe, and to find harmony amongst all the distortion that's in the air. By the Fire is a very simple title as such, but it's definitely about communication. That's just the nature of the record. It was all done before the pandemic, but the thing is, it was put together during the pandemic, so to be in quarantine defined a lot of the narrative, too, as far as how I sequenced it, and just the vibe of it. It's informed by this time of contemplation and anxiety—this new world we're living in together."

TIDBIT: Although Moore's new release was recorded pre-COVID, he explains that “it was put together during the pandemic, so to be in quarantine defined a lot of the narrative, as far as how I sequenced it, and just the vibe of it. It's informed by this time of contemplation and anxiety—this new world we're living in together."

At its core, how does this band function differently from the way Sonic Youth did?

Well, Sonic Youth was a thing unto its own. It was a sum of its parts. Even though I might have been the instigator, we grew up together, and there was no hierarchy in the band. That's something that I don't think can be repeated, and I'm not really willing to repeat it. I didn't really want to start a band again and have that kind of relationship.

I spent 30 years playing with Lee Ranaldo, and Lee is such an amazing guitar player, and he was always looked upon as possibly the lead guitar player in Sonic Youth. And if there was one, it was him, but that was never the relationship we had between all of us. Lee had his own voice, so we called him the Lee guitar player. With James, there's nothing he really plays like Lee—and I never really wanted to have that replicated anyway, because I thought that would be rather a clunky thing to do. It just didn't feel right.

When I started talking to James, I knew he was quite a different guitar player than Lee is, so that sets the music apart. Deb does that with her bass playing, too. I never tell her at all what to play. She just somehow finds that magical root that drives the song. So I've been really loving playing with this group. It's been like eight years, almost. We've been together longer than most groups, historically, you know? With Steve and Jem, the drummers have changed around a little bit, but James and Deb and myself have been a nucleus for quite some time now.

For one thing, you've talked about turning James loose on guitar solos, and he takes a pretty massive one on “Cantaloupe."

That was just a simple song—something that I wrote really quickly and thought, “Oh this is cool; let's do this as a band." So I showed it to the band and we put down the basic track, and I said to James, “You know, this section would really smoke with a lead." And he did it in one take. He went in there, in the alternate tuning [C–G–D–G–C–D], laid it down, and I was just like, that's ridiculous. So he has that ear and that ability. He can shred in that really traditional way, but he always has this edge, this sense of jumping off the experimental cliff, you know?

Thurston Moore gets down with one of his three touring Fender Jazzmasters. Fender created a signature Jazzmaster model for him in 2009. Photo by Jim Bennett/Photo Bakery

You played a couple of Jazzmasters on the Rough Trade set. Are those your main guitars?

I have a few, but my central guitar is this 1959 beauty [a gift from Patti Smith after Sonic Youth's equipment van was stolen in 1999]. Then I have another one, from '64, which I usually have in the C-tuning, and a signature Jazzmaster that Fender made for me about 10 years ago [usually tuned to D–D–A–F#–A–D]. It's out of production, but they had two Sonic Youth signature guitars: a Lee Ranaldo and a Thurston Moore. I think Lee put different pickups in his, and his frets are different. I have these jumbo frets on mine, so there are some similarities and some differences. I designed it with the Sonic Youth guitar tech I was working with at the time, Eric Baecht—a great guitar tech. He's worked with Nels Cline and Wilco, and Queens of the Stone Age, but before those notables, he was my tech. He recognized what aspects of the Jazzmaster I was utilizing for my own playing style, and just ran with it.

Recording is really indicative of the space and how the engineer is miking things. I'll usually bring in the one amp I have here in London, which is a Fender Hot Rod DeVille. It's a 2x12 combo that I can really dial in. But sometimes in the studio, a smaller amp is a little better as a recording amp. For live gigs, the Hot Rod is good, but I generally like a 4x12 bottom with mid-wattage speakers, like Celestions, powered by—I wish I owned one—a vintage Hiwatt head, like a 100-watt head or even a 60-watt head. When we tour the U.S., both James and I use a couple of 4x12 bottoms, and we usually power them with an old 100-watt Peavey [Roadmaster] tube head. Those are like the Mississippi Marshalls, you know? But that stuff…. Let's just say that hauling around heavy gear is not my thing these days [laughs].

Are there any other guitars you play on the album?

It's pretty much just those Jazzmasters. There are a few pieces where I'm playing a 12-string Martin. I also have a Fender 12-string—a late-'60s model that was only in production for a few years. That's a wonderful guitar. My girlfriend bought that for me on my 60th birthday a couple of years ago, because I was commissioned to do a piece for twelve 12-string guitars at the Barbican Centre here. That was a lot of fun. I did a piece for twelve 12-string electrics, and twelve 12-string acoustics, in one night—two one-hour pieces.

You've made a point of saying that you're not a pedal geek, but you still have some interesting pieces.

Yeah, there's this thing about going out on tour, where guitar players go to guitar shops in any given city. I go to second-hand bookshops and record stores. I have a couple of guitars, so I'm cool. The fetishization of trying out guitars and pedals, that's a certain breed, and that's James. And like I said, you know, for me to be playing with somebody like James, who just lives and breathes guitar playing, is great.

But having said that, on the song “Locomotives," I use this [Electro-Harmonix] Cathedral pedal, because basically it creates this beautiful looping effect that I really like. And the only reason I use it is because I found one at a church basement sale for next to nothing. It was going for like three dollars, so I had to buy it. And I like the name because it has a pretty solid religious connotation [laughs]. But I found one setting, and that's the one I always use. That's the one you're hearing on that song. I use it on a few different songs as well—just this one setting that I have locked in. [That setting is: hall mode, with blend at 1 o'clock, reverb time at 2, damping/tone at 2, and feedback and pre-delay at 4.]

Guitars

1959 Fender Jazzmaster

1964 Fender Jazzmaster (with Seymour Duncan Antiquity II pickups, Mastery bridge and tremolo)

2009 Fender Thurston Moore Signature Jazzmaster

1966 Fender Sunburst Electric XII

Amps

Peavey Roadmaster head

Marshall 1960B 4x12

Fender Hot Rod DeVille

Hiwatt Custom 100 DR103

Hiwatt SE4123 4x12

Effects

Pro Co Turbo RAT

Jim Dunlop Jimi Hendrix Octave Fuzz

Electro-Harmonix Cathedral Stereo Reverb

Electro-Harmonix Metal Muff

Sovtek Big Muff

Ernie Ball VP Jr.

Boss TU-3W

MXR Phase 90

TC Electronic Hall of Fame Mini

Strings and Picks

D'Addario NYXL (.011–.054)

Fender Super 250s 12-string sets (.010–.046)

“Locomotives" really stands out, because it sounds like such an overt tribute to Glenn Branca and that real sense of adventure he brought to composing for electric guitar. Can you talk about his influence?

Oh, definitely. I first saw him play in '78 or '79, in a couple of really wildly experimental groups he had: one called Theoretical Girls and another called the Static. But it wasn't until he stepped away and started his own instrumental guitar ensemble groups, and he was writing compositions for them—that was where I really took notice. He was actually accomplishing something that I was hearing in my head and my body at the time, and then all of a sudden there it was. I heard this six-guitar-and-drums group, and it was ferocious. And I realized he had alternately tuned the guitars. I think at the time I saw he had six guitars, with one guitar tuned to low E, and another guitar all to the fifth string, and so on, so it was like one big guitar. I might be wrong about that, but I like to think that's what it was.

Then I answered an ad in the newspaper when he was looking for guitar players, and I ran over to his place. And I actually started playing in his group. Lee was already in there. Lee and I were just connecting at that point anyway, because we were in different bands and kind of played together at the time.

Glenn wasn't the only one who was working with alternate tunings and expanding the guitar from its traditional nature. Rhys Chatham was working in that respect, and some of the players in the no-wave bands like Pat Place, and Connie Burg, who was in a band called Mars, were doing really interesting work with guitars. But Glenn was probably the most exciting, and he had really intensified ideas about what could happen with mass guitars in different tunings, and that was really informative. So to play with him, for both Lee and I, it really was something that we always reference in Sonic Youth a lot, amongst some of the other things we were referencing, like Tom Verlaine and Television, and the Modern Lovers—and Neil Young, for godsakes.

I did a record last year called Spirit Council, which is three CDs in a box, and each CD was just one long instrumental guitar composition. In a way, it was my fare-thee-well to that inspiration, to some degree. I wanted to get a lot of that work out of my system, so I wrote these long pieces. And after I had done all that music and toured it quite a bit, I was thinking about how to get back to writing more approachable songs, with lyrics and vocals, without losing some of the Branca-esque aspects. And “Locomotives" is pretty much that.

“Siren" comes across with this really sweet underlying guitar melody in a major key, and then over time it pulls you in with the switch to a more moody, minor-key sound before it breaks apart and then comes back to the head. Did you work this out in the studio as an improv first, or did you have all those sections written when you came in?

I had it all composed beforehand. There was a piece of music that I'd been working on in the C tuning I use. It's a tuning I really love to play in. The first two songs on the record, “Hashish" and “Cantaloupe," are in that tuning. So I think I was going through some different chordal ideas, and I found a way to create this song journey with these different pieces that fit together. That's all it is. As soon as I felt like it worked, and it created a unified piece of music as a song, that was it. I showed it to the other three members of the band and we worked on it. That repetitive measure at the beginning is a little tricky. I almost tried to call that out as I was playing it, but it gets easier once you figure out the cycle of it. I feel pretty happy with that composition.

Moore's main guitar is this 1959 Fender Jazzmaster that was a gift from Patti Smith, after Sonic Youth's gear truck was stolen in 1999. His '64 Jazzmaster has a Mastery bridge and Seymour Duncan Antiquity II pickups. Photo by Debi Del Grande

It's a really sticky melody. Being here in New York, that one in particular is actually a great song to listen to while you're walking around in the city.

Oh, that's good. I love to hear that. New York City is so important to me. That melody was really its own thing, and it needed to be partnered with something, and these three things came together and they were all in the same sort of melodic place. It was just a marriage of these parts that sort of worked.

How are you feeling about where music is headed, especially under the conditions we're all dealing with now?

You know, I was very happy to hear that this record was being released at the same time as Public Enemy's record, and at the same time as Bob Mould's new record. And there's a band here in England that everybody has a lot of excitement about called Idles, and they have a new record out. I find all these voices to be really strong, and they all have stories to tell. Then you look at the fact that people are taking to the streets, regardless of being quarantined, in complete and utter protest and resistance to having so much violence perpetrated upon their communities … you know, there's fire in the street. Whatever source it comes from, there's fire in the street. And I'm very curious to hear more voices come out of the music world right now, just to find out how that fire might shape what they're creating.

On dual Jazzmasters, Thurston Moore and James Sedwards lead Moore's four-piece group through “Hashish," “Siren," and the textural epic “Locomotives," all from the new album, By the Fire.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)