Most musicians of our modern era have been influenced by the blues in some way. The blues is an important source of study that can add impact and depth to your music. Simply listening to players like B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Michael Bloomfield, and others will not only give you a better understanding of the genre but it will help to shape your own style as well.

Playing blues guitar is largely based on feel, but what exactly is it? Words can't adequately describe the blues, since it's invisible until a player animates him or herself with it. Some people seem to have it in abundance. As an 18-year-old guitarist in the early '70s, I saw Muddy Waters at the Golden Bear in Huntington Beach, California. The band worked their way through many of Muddy's most well-known songs and I thought to myself, "I guess these are just popular songs?" I didn't get it.

Then the band went into a slow blues near the end of the set and Muddy finally broke out a solo. Oh man! His red Tele came to life through that Super Reverb, and he just lit the place up. I'd never heard anyone play remotely like that. Everyone went crazy—even the other musicians on stage. It was as if the sound came from out of the clouds. The way he connected with the audience was something special. It was that night that inspired me to learn as much as I can about blues guitar. In this lesson, I'm going to share some foundational techniques to get you on the right path.

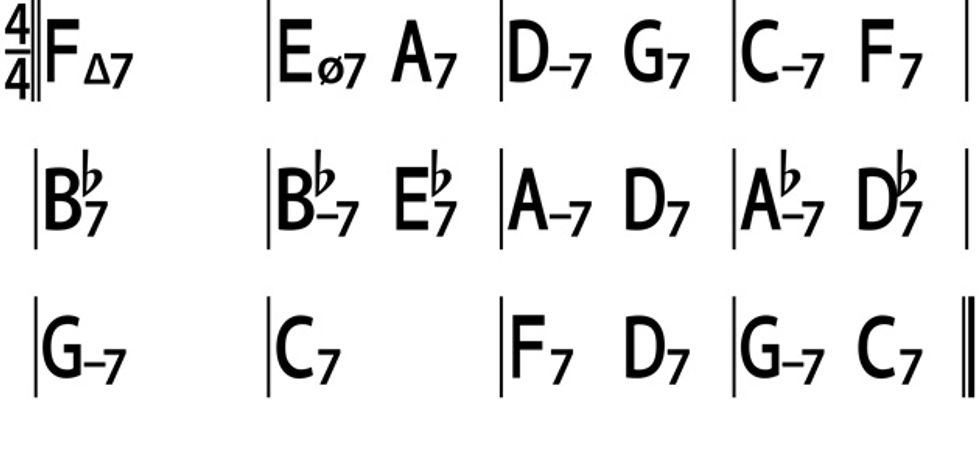

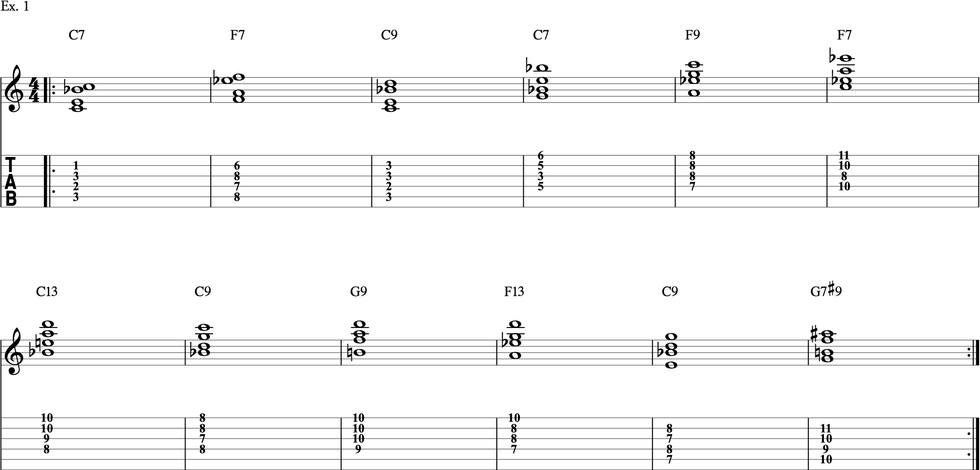

By far the most common blues song form is the 12-bar blues. You can go anywhere in the world and call a "blues in G" and everyone will know exactly what's happening. In Ex. 1, I've written out a way to comp through a 12-bar blues with a mixture of simple and complex chord voicings.

Each of the following examples progresses through a slow 12-bar blues in the key of C. I would work on one riff or exercise until I had it down, sometimes for hours. A classical guitarist I know said he practices with the goal of playing it twice as good as needed in a performance. That way even if he's having a bad night it still sounds good.

Ex. 2 is a must-know intro riff. Everything that goes into this is important to give it its distinction. Country sounds like country, jazz sounds like jazz, so blues has got to sound like blues. Practice and listen closely to as many players as you can. This riff will kick off a blues in C, but learn how to move it around so you aren't stuck in one key.Ex. 2

Bending in tune is an essential skill no matter what style you play, but it can make or break a lick like Ex. 3. When going from the 10th fret on the 4th string to the bend on the 10th fret on the 3rd string, use different fingers, like the second finger to the third finger. Then, put the first, second, and third fingers all on the 3rd string for the power bend.

Ex. 3

This next riff (Ex. 4) needs great technique in order to use it. Notice the big wobble over the last sustaining bend. Good vibrato is a very hard thing to develop. Some people rely on the whammy bar for this, but we should use our left hand. It takes arm and finger strength. Grrr!

Ex. 4

Extended blues riffs are mostly combinations of short riffs played in succession and connected to each other. Piano players can't bend notes, so they construct melodic ideas instead of relying on the kind of guitar tricks we use. There's a lot to be learned from that kind of thinking. Notice it's a simple eighth-note rhythm over the triplet hi-hat figure, which makes it tricky to get, so lay back and don't rush (Ex. 5).

Ex.5

Ex. 6 demonstrates how to play over changes. In other words, over the G9 chord I use a G minor pentatonic with a natural 3 (G–Bb–B–C–D–F) and instead of sticking with that over the F13, I move it down a whole step (F–Ab–A–Bb–C–Eb).

Ex. 6

Turnarounds usually occur in the last two measures of a 12-bar blues. It's a theme that signals to everyone that we're on our way back to the top of the form. In Ex. 7 I've written out a riff that uses a series of sixths that descend chromatically.

Ex. 7

These are some cool ideas to get you started in this rich tradition. Once you're comfortable with these licks, make sure to move them to other keys. Take your time and really focus on the feel. The blues is simple, but that doesn't mean it's easy!

This article was updated on September 10, 2021