Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Beginner

Lesson Overview:

• Combine string skipping and open strings with pentatonic scales.

• Understand how to play one-note-per-string scales.

• Develop a more vocal phrasing technique.

Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson's notation.

Who doesn’t love the pentatonic scale? It is difficult (if not impossible) to find a more versatile, cool sounding, and finger-friendly pattern on the guitar—five notes and seemingly endless possibilities.

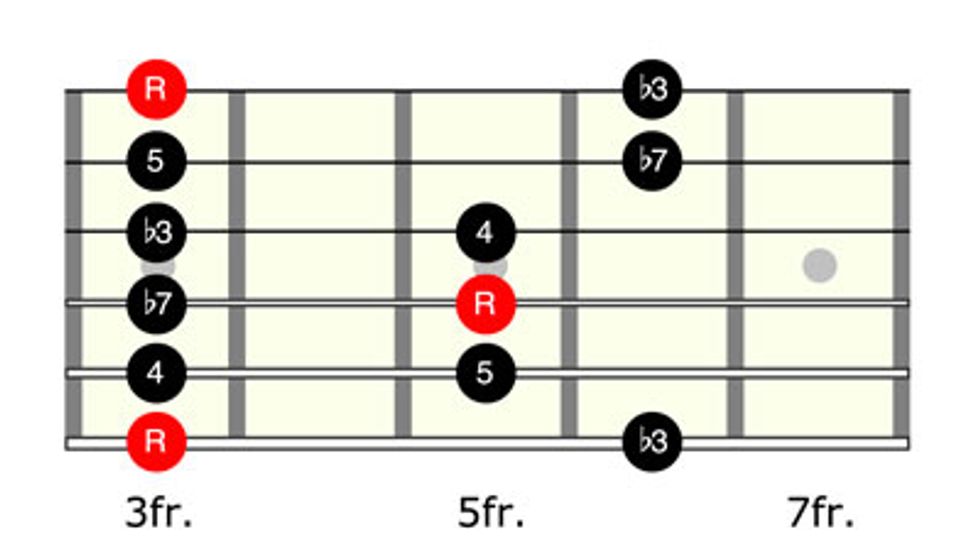

But there’s a downside. The pattern is so easy to play—particularly the so-called “box” in Ex. 1—that it’s tempting to get lazy and overuse it. Let’s call the scale in this example by its more formal name: G minor pentatonic (G–Bb–C–D–F).

Ex. 1

Many players find themselves mimicking the same sounds we’ve been hearing on the guitar since Chuck Berry’s 1955 hit, “Maybellene.” Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but with just a little revisualization, the pentatonic scale can also offer more modern sounds. We’ll focus on accomplishing this by borrowing (and expanding on) ideas from such forward-thinking players as Eric Johnson, Carl Verheyen, Paul Gilbert, and Joe Diorio.

Let’s jump right in with a shifting lick in G minor (Ex. 2) that—with just a few simple slides—allows us to make our way from the 3rd fret all the way to the 15th fret using an easy, repetitive fingering pattern. The articulation of the slides makes this ascending run sound decidedly different from conventional “box” playing.

Click here for Ex. 2

Ex. 3 is similar to the previous example, except I omitted the C note. This gives us a Gm7 arpeggio (G–Bb–D–F) in three ascending octaves. The fingerings for the first two arpeggios should be fairly intuitive, but experiment with the last one to facilitate the reach up to the 15th fret.

Click here for Ex. 3

Ex. 4 is my favorite Eric Johnson-inspired lick and it’s relatively easy to play fast. The lick appears to be little more than the E minor pentatonic (E–G–A–B–D) played in three different positions. If you pay close attention, you’ll see that the line keeps jumping backwards as it shifts position. Try playing this lick two ways: first by picking every note and then using hammer-ons.

Click here for Ex. 4

The next few examples take a decidedly non-linear approach. Über-shredder Paul Gilbert and his string-skipping runs inspire Ex. 5 and Ex. 6.

Click here for Ex. 5

Click here for Ex. 6

Legendary jazz guitarist Joe Diorio has a unique approach to creating interesting lines. In Ex. 7 we use a variation of his octave displacement technique to create an angular phrase.

Click here for Ex. 7

The next lick in Ex. 8 requires a bit of fretting-hand stretching. There are two great things about this concept: The hand position doesn’t change and you can duplicate notes on different strings. Also, since there aren’t many different notes, this run can work over Am, Em, and Dm. Ex. 9 is a variation loosely based on an arpeggio approach.

Click here for Ex. 8

Click here for Ex. 9

The next two examples build on that idea, but add in some grace-note slides. In Ex. 10 we have a one-note-per-string phrase that ends up outlining an Am7 (A–C–E–G) arpeggio. The graceful slides come into play in Ex. 11.

Click here for Ex. 10

Click here for Ex. 11

Finally, we end with a flashy lick in Ex. 12 that combines open strings with an Em pentatonic pattern. Since all the open strings fall within the scale you can create countless variations by moving the passage around the fretboard.

Click here for Ex. 12

One final important note: Please, please, please come up with some rhythmic variations for these licks. Those variations are essential to making these licks your own. There are literally thousands—maybe even millions—of variations you can generate using just the five notes of the pentatonic scale. And remember, it’s the sparseness of notes that makes the scale so protean.